There's an element of perversity in casting Javier Bardem as a quadriplegic. Whether he uses it exuberantly (as he did in "Before Night Falls") or holds it in reserve (as he did in "The Dancer Upstairs"), Bardem is defined by his strapping physicality. (He might seem nearly hulking if he weren't such a lyrical actor.) And he has the sort of regal profile that wouldn't be out of place on an ancient Roman coin.

Bardem spends almost all of his performance in Alejandro Amenábar's fine new film "The Sea Inside" ("Mar Adentro") in bed. He's playing the Galician Ramón Semprado, paralyzed from the neck down in a swimming accident as a young man, who badgered the Spanish government for 30 years to win the legal right to commit suicide. It's as if Bardem has chosen the role as an acting test, to see if he can retain his expressiveness while severely restricting his physical resources, and without bathing Ramón in the false saintly nobility that many actors in a part like this would seize on as a fast track to awards.

The film isn't in a league with "My Left Foot" or "The Elephant Man," the great movies about intelligence and spirit trapped in a body that threatens to extinguish them. (Part of that may be that the screenplay, by Amenábar and Mateo Gil, does not allow for the emotional, nearly operatic highs and lows of those pictures.) But like Daniel Day-Lewis and John Hurt in those movies, Bardem plays the man and not the handicap.

As Bardem essays Ramón's limited physical action, he makes you feel both the memory of movement and Ramón's desire to be able to force his will to overcome his crippled body. Bardem concentrates all of Ramón's passion, strength and intelligence in his large head, the only part of him that's mobile. His features are frequently in a grin, as if his situation has left him an observer able to savor the ironies everyone else misses.

No recent movie's success was more surprising than Alejandro Amenábar's last picture, "The Others." A ghost story that operated entirely on mood and suggestion in the tradition of "The Haunting" and "The Innocents," it was exactly the sort of movie that no one expects to be a hit anymore.

"The Sea Inside" is another sort of surprise: exactly the sort of movie we don't expect from the triumph-over-adversity genre. That may be because, arguably, it isn't about a triumph. Ramón believes that his paralysis has stripped his life of dignity, not only because he needs to be fed, dressed and cleaned as an infant would but because he has no means to fulfill even the slightest of his desires: Forget even thinking about making love to the women he seems to attract without even trying -- Ramón can't so much as scratch his nose or turn the pages of a book without the help of a computer his nephew and elderly father have rigged up for him.

If "The Sea Inside" were a typical entry in this genre, it would be set up to show that despair has gotten the better of Ramón, to show how he finds his inner strength and realizes life is worth living after all. That position is represented by a meddling priest (are there any other kind?), also quadriplegic, who turns up at Ramón's convinced that only someone unfulfilled, without love, could want to end his life. It's an arrogant assumption. Ramón has the benefit of living with an older brother so devoted that he quit his fishing business and became a farmer to be able to better care for Ramón. His sister-in-law, Manuela (the marvelous Mabel Rivera, who has some of the earthiness that was always a joy to behold in actresses like Anna Magnani and Margarita Lozano), tends lovingly to him (at one point, she says she has always thought of him as a son), and Ramón's nephew (Tamar Novas) is a talented boy who Ramón goads and encourages in his studies.

That family gives Ramón more love and support than many people who aren't handicapped have. But the movie stands with Ramón in his insistence that he should be allowed to end his life. And that's what makes the film so singular, because in taking Ramón's side Amenábar quietly and firmly contradicts all that we've unthinkingly come to parrot about the handicapped.

No one wants to go back to the time when the handicapped were treated as if their physical helplessness made them like children. But acknowledging what the handicapped are not capable of has become tantamount to an insult. Ramón is merely stating the obvious -- that a severely limited life is, of course, less fulfilling, more frustrating, potentially less dignified, than the lives lived by those who have the full use of their limbs. He's rejecting all the feel-good, well-intentioned malarkey doctors and social workers and advocacy groups routinely claim for the "useful" life the handicapped can lead. (Is there a more insulting word to apply to the concept of life than useful?) Ramón's insistence on speaking only for himself, and not as part of the handicapped, is, in a contemporary context, extremely politically incorrect. And it's because of Amenábar's ability to make fine moral delineations that his hero's individuality, the very thing that makes Ramón so admirable, also makes him, at times, a bit of a monster.

Because he is dependent, Ramón, in effect, needs someone to kill him. He devises a scheme that will save anyone who agrees to help him from facing prosecution. But apart from a moment when Ramón tells his brother, who absolutely forbids any suicide from being carried out in his house, that he doesn't want to be a burden to his sister-in-law and nephew should she be widowed, Ramón stays almost myopically focused on the legal issues when it comes to involving other people in his suicide. Ramón is not innocent of the selfishness of suicide; not only does he expect the people he leaves behind to bear the loss, he expects them to effect the loss.

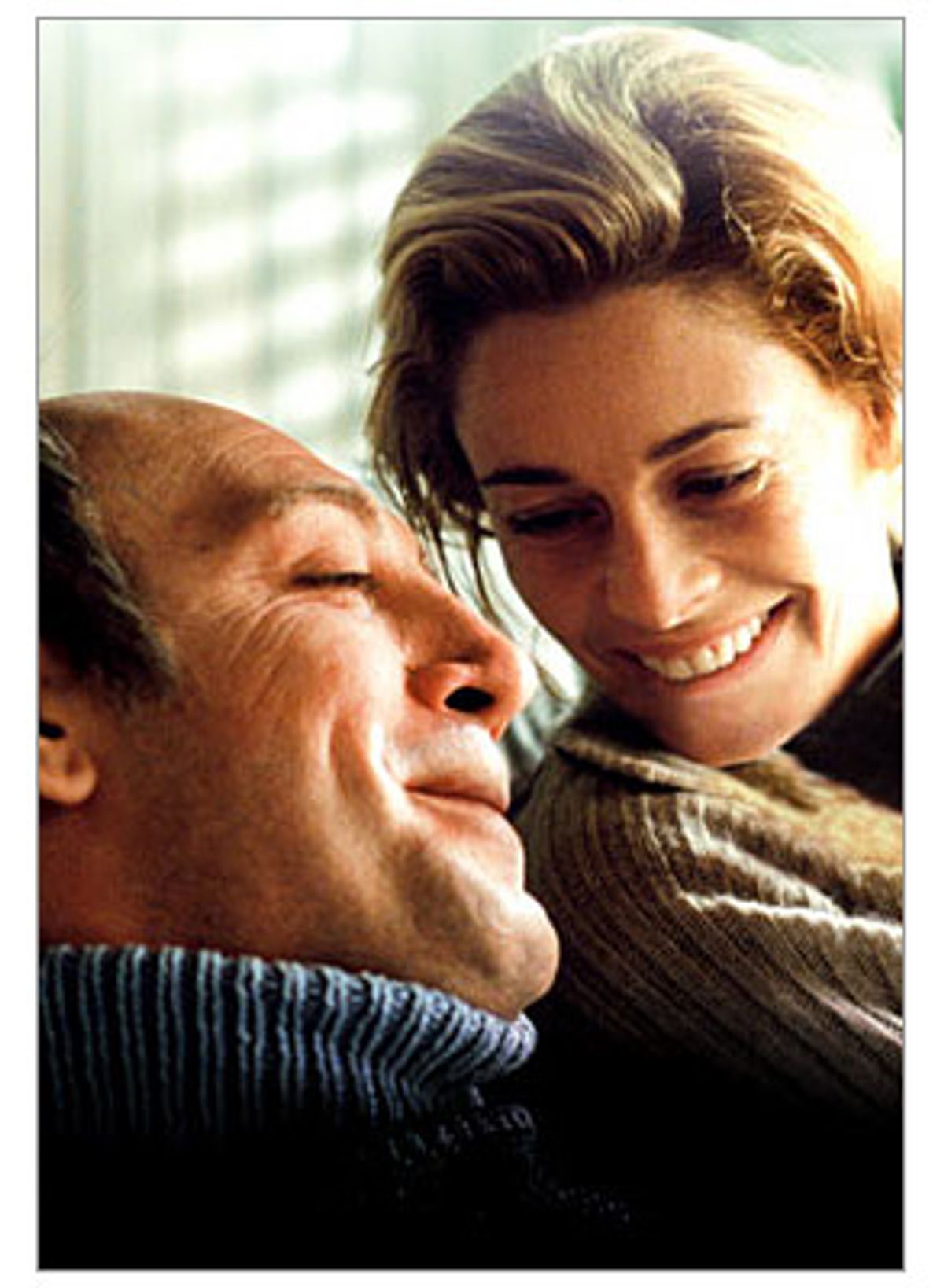

"The Sea Inside" isn't simple-minded like Marsha Norman's vile play "'night, Mother," in which a woman about to kill herself spends the last hour and a half of her life torturing her mother with advance knowledge of what she plans. Amenébar doesn't shortchange the feelings of the people who'll survive Ramón. The actors in supporting roles are such a varied and vivid presence that they make us question Ramón's determination to die at every step. In addition to the trio of actors who play his family, there's Belén Rueda, wonderful as Julia, the lawyer who agrees to represent Ramón in his campaign to win the right to die. Rueda is one of those actresses whose radiance is tinged with a touch of the haggard. Julia is suffering from a degenerative disease that makes a series of increasingly debilitating strokes inevitable.

And it's another sign of Amenábar's willingness to make his drama unresolvable that we're not sure what to think when Julia announces that she wants to follow in Ramón's footsteps. She seems to be acting as much out of a romantic impulse as out of a rational decision to escape her inevitable physical deterioration. Rueda gets both Julia's courage and the irrationality of a romantic, utopian streak. As Gené, a right-to-die advocate who befriends Ramón, Clara Segura has an uncomplicated warmth. Lola Dueñas plays Rosa, a woman who goes to meet Ramón after seeing him on television. Rosa is one of those needy egomaniacs who find a way to trump everyone's misery with their own sack of woe. Maybe I've known too many people like Rosa or maybe Dueñas is too convincing. Whatever it is, she's so believable she drove me crazy.

Even when a potentially mawkish movie like this one is made with intelligence that escapes clichés and platitudes, it has to have a charismatic presence at the center to work. Amenábar is lucky that in Javier Bardem he has not just one of the greatest film actors now working but also one of the most physically beautiful. That's not to slight Amenábar. A ghost story like "The Others" and a film like "The Sea Inside" might not seem to share much. But both benefit from a type of restraint (the refusal to go for easy scares in the former, or for easy tears in the latter) that marks a director of real taste.

And real sensibility, too. Amenábar composed the score for "The Sea Inside," which is, of all things, Irish in flavor, loaded with the mournful and celebratory sound of uilleann pipes. That seems fitting. There's a combination of fatalism and hard-edged humor at work in "The Sea Inside" that you can imagine Irish writers would feel right at home with. When Bardem lets a wry smile cross his face, we feel as if we've seen the shrug that should accompany it. And though, in a dream sequence, Ramón flies (we don't see it, we watch from his point of view as the land moves by beneath him), all the suppressed longing in Bardem's performance makes you feel you've been looking at a man who at every moment is ready to soar.

Shares