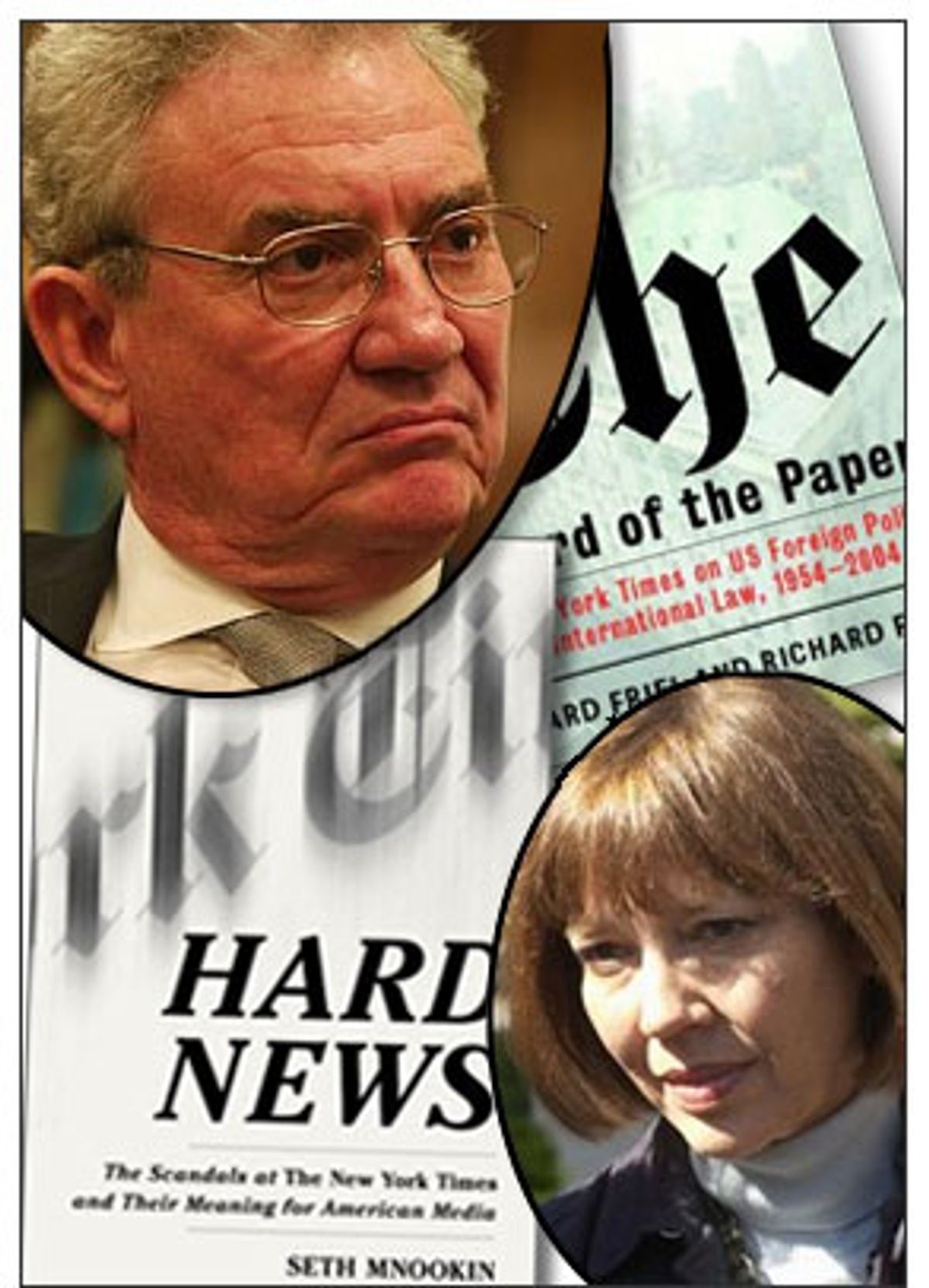

Near the end of "Hard News," his gripping account of the Jayson Blair scandal and the brief, disastrous reign of former New York Times executive editor Howell Raines, media reporter Seth Mnookin makes an offhand comment that pretty much nails the peculiar status of the Times in American society. "For the Times to be the Times," Mnookin writes, "its employees ... need to be willing to sublimate their own egos to serve a larger, quasi-public good."

Mnookin means this to be another log on the pyre he's building under Raines, who is depicted in "Hard News" as a vainglorious tyrant, far more the book's villain than the pitiable Jayson Blair, a bewildered young man perhaps suffering from mental illness who should never have found himself in a position to disgrace the nation's leading newspaper. But what sticks with me here is the notion that the New York Times -- a for-profit media corporation that has been controlled by a single family for the last 108 years -- serves a "quasi-public" purpose. While this is clearly true, the purposefully ambiguous phrasing needs some unpacking.

Every morning's edition of the Times defines what the terms of discourse will be on that day for the political, intellectual and media elites of the United States. Like almost everyone else I know, I read the Times first thing in the morning, and I did so long before I moved to New York. Savvy as we may all think we are about the Times, and much as we may scrutinize and second-guess its perceived missteps, the decisions made by its editors dictate our agenda more than we would like to admit.

During Salon's daily conference call of desk editors, there is nearly always some discussion of the day's Times: How has the paper's coverage of Bush, or of Iraq, shifted recently? What books or movies were reviewed? What trends were spotted embarrassingly late -- or distressingly early? What stories has the Times covered that we've missed? And what stories do we need to jump on before the Gray Lady airs them out?

If there's a connection between Mnookin's measured and judicious "Hard News" and "The Record of the Paper," Howard Friel and Richard Falk's blistering critique of what they describe as the Times' chronic misreporting of U.S. foreign policy, it's that both books remind us that the Times is fundamentally a business, and its reputation for impartial and careful newsgathering is fundamentally a marketplace commodity. It's what the Times is selling us. Like all other commodities, it is shaped by the conditions under which it is sold: It goes up and down in value, it is repackaged and redesigned to seem more appealing, it is understood by different consumers (that is, readers) in different ways.

Of course, it's true that the press in general bears an important public trust in American democracy, at least in theory, and the Times' dominant position brings with it a disproportionate responsibility. But setting the civics lesson aside, the true mission of the New York Times is not to serve the public but to serve its owners and shareholders. It's a corporation striving for market share in a capitalist economy. It's a brand -- the most prestigious brand name in journalism -- and the decisions of its editors and managers, whether good or bad, are seen as affecting the long-term viability of that brand.

This understanding takes us a good distance toward answering a burning question that both these books bounce off en route to their desired targets -- which are, in Mnookin's case, an indictment of Raines' chaotic regime, followed by reassurances that the essential chemistry of the Times has reestablished itself; and, in Friel and Falk's case, a riveting and despairing analysis of the paper's ideological self-castration.

Along the way, both books briefly (and unsatisfactorily) ponder the jarring disparity between the Blair scandal and the case of Judith Miller, the Times reporter who did more than any other single individual, except perhaps George W. Bush, to spread the notion that Saddam Hussein's regime possessed weapons of mass destruction and, by extension, that war with Iraq was both necessary and inevitable.

As Mnookin's chronicle captures in high page-turner style, l'affaire Blair had the media world (and, for a week or so, the whole country) enthralled during a slow news cycle in the spring of 2003. And no wonder: It was a gripping tale of a breathtaking con job and unbelievable mismanagement, leavened with schadenfreude and seasoned with those inescapably American ingredients, racial guilt and hostility.

A young and inexperienced African-American reporter is fast-tracked to the front page, despite repeated warnings from his editors and supervisors that he can't be trusted. Suffering from who knows what combination of mental instability, anger, drug addiction and exhaustion, he perpetrates the most massive and ambitious series of frauds in the recent history of journalism, "reporting" dozens of stories from places he never visited about people he never met.

The scale of the Times' response was every bit as impressive as the scale of Blair's deceptions. After an editor at the San Antonio Express-News informed the Times that Blair had apparently plagiarized an article from his paper about a Texas woman whose son was missing in action in Iraq -- and after Times editors realized that Blair had never traveled to Texas and that his story was entirely bogus -- a team of five Times reporters, three editors and several researchers spent a week, working almost 24/7, digging into Blair's reporting career. Acting as in-house independent investigators, they interviewed Blair's editors and colleagues, sought access to his personnel records and expense reports, and had a series of tense encounters with the paper's upper management, including Raines, managing editor Gerald Boyd and publisher Arthur Sulzberger Jr.

A former Newsweek reporter who covered the Blair scandal at the time, Mnookin provides an admirably full account of this ultimate crash-reporting assignment and the foxhole mentality it bred among the investigative team. (Full disclosure: Mnookin was a frequent contributor to Salon from 1998 to 2002, and I've met him two or three times.) It's compulsive bedside reading for journalism junkies. As reporters Dan Barry, David Barstow, Jonathan Glater, Adam Liptak and Jacques Steinberg began to excavate Blair's trail of deceit, they realized, first, that the scope of his deception was massive and, second, that part of the story was about the dysfunctional management style and poor communication of the Raines-Boyd regime.

They were unearthing the biggest scoop of their careers -- and it was a scoop that was going to fling mud all over their bosses and the exalted reputation of their newspaper. Barstow cracks: "We were all half waiting for the time when we'd be told, 'We really need a seasoned journalist to lead the resurrection in the Westchester Weekly section ... And by the way, you start on Monday.'"

In the end, the team's 7,100-word report was published, without management interference, on May 11, 2003. Mnookin rightly observes that it was a document that would change American journalism. The article didn't merely catalog Blair's career of plagiarism and fabrication in gruesome detail; it described them as a "profound betrayal of trust and a low point in the 152-year history of the newspaper." No major journalistic institution had ever undertaken such a public self-scouring, and anyone who buys into the newsroom bromide that the only cure for bad reporting is good reporting had to feel heartened. Some within the paper, according to Mnookin, felt that Barry, Barstow, et al., didn't go far enough in crucifying Raines and Boyd; others found the whole thing an exercise in overwrought navel gazing.

But for most readers, I suspect, and most journalists outside the Times, the article was impressive evidence that the paper's management wouldn't try to sweep the Blair scandal under the rug and was committed to repairing the damage as best it could. As Mnookin further documents, a near-rebellion of Times staffers against Raines and Boyd cost the editors their jobs and led to the reign of current executive editor Bill Keller, a more conventional Timesman who, it seems, is trying to shape the paper more gradually and subtly, and who lacks Raines' good-ol'-boy charisma, far-reaching vision or fatal hubris.

Before we get to Judith Miller, and the question of why she still has a job despite disseminating lies and propaganda whose effects put Jayson Blair's fictions to shame, let's consider the fascinating case of Howell Raines. Mnookin honestly tries to do Raines justice, but I don't think he succeeds, partly because Raines refused to talk to him (most of Mnookin's many sources come from the anti-Raines faction within the Times) and partly because Raines is so difficult to figure out. How did a man who had demonstrated such extraordinary political savvy in his climb up the Times' masthead become (at least in the view of many, perhaps most, of his subordinates) an isolated autocrat, widely disliked and hopelessly out of touch with his own newsroom?

Mnookin believes that Raines was essentially too fat-headed and ham-fisted for the job, and was more interested in his own legacy -- and even in his status as a superstar editor and New York gossip-column character -- than in the greater good of the newspaper. There's probably something to this; I've worked for these kinds of slave-driving, door-slamming, editorial visionaries before, and I've never liked it. (I was involved in a staff coup against a talented, difficult editor at a San Francisco weekly about a dozen years ago.)

Raines sounds like an impossible boss, in Mnookin's account, and his attempt to reshape the Times in his own image was foolhardy. But I pretty much agree with Raines' central critique, which, as I read it, was that under previous editor Joe Lelyveld the paper had grown staid and complacent. The Times was too often a follower on big stories rather than a leader, the cultural coverage was insipid to the point of irrelevance, and the overall feeling was that of a vast operation of dusty, dull competence rather than daring or ambition.

As Friel and Falk point out in "The Record of the Paper," the Times, before Raines, had always conspicuously avoided crusades. Raines' efforts to change that by pursuing many of his favorite issues, via both news coverage and the editorial page, struck many observers as especially embarrassing. (In the case of his extended and exaggerated campaign against the Augusta National Golf Club for its discrimination against women, it also backfired in spectacular fashion.) By the same token, for progressive readers it was heartening to see the Times vigorously covering abortion rights, gun control and affirmative action, top items on Raines' avowedly liberal agenda. Raines was right, at least personally, about the PATRIOT Act and the Iraq war (although the paper editorially waffled on both). My personal, heretical view is that Raines was also right in his low opinion of Bill Clinton, but let's leave that argument for another time.

Clearly, Raines was a dismal manager with terrible communication skills, but as a reader, I found the Raines-era Times more engaging, more packed with must-reads and more alive to the issues of the day than it had been for several years previously. On the other hand, it also published both Jayson Blair and Judith Miller, and that happened, according to Mnookin, because of the increasingly autocratic management climate fostered by Sulzberger, Raines and Boyd. So, much as I want to admire and sympathize with the eccentric, big-dreaming Alabamian, Raines' lasting legacy at the Times is a sad and shameful one.

One of the very few points of agreement between "Hard News" and "The Record of the Paper" is that Miller's anonymously sourced front-page "exposés" in late 2002 and early 2003 about the alleged Iraqi WMD -- which now appear to have been false in virtually every detail -- got into print because of the Times' overpowering institutional predilection to hew to the perceived political center. Mnookin says that half a dozen Times sources have told him that Raines seized on Miller's WMD stories as a way to establish that his liberal views weren't driving his editorship.

For Howard Friel, an unaffiliated media watchdog, and Richard Falk, a retired Princeton law professor, the Miller stories are part of a far more insidious and sinister pattern. They argue that the Times, over the course of five decades, has consistently ignored questions of international law (which the U.S. has violated on numerous occasions) and treated government pronouncements with an almost childlike credulity. Their tone is sometimes intemperate -- it may not be incorrect to observe that many people around the world view Israeli premier Ariel Sharon as a terrorist, but it isn't especially helpful -- and their long, densely argued book is unlikely to reach beyond its Noam Chomsky-Howard Zinn core readership. But their case is difficult to refute.

Essentially, Friel and Falk contend that as American political discourse has crept to the right, the Times has crept along with it, maintaining a relative position that can plausibly be perceived as to the left of Republican orthodoxy but slightly to the right of the Democratic Party mainstream. During the run-up to the Iraq invasion in early 2003, for example, the paper tortured itself and its readers with a series of yes-but-no, no-but-yes editorials, finally opposing the war at precisely the moment it had become inevitable. Then there was the infamous story by Michael Ignatieff in the Times Magazine, suggesting that some coercive torture-lite procedures might be necessary to combat terrorism -- which was sent to the presses just before the first photographs of atrocities at Abu Ghraib reached our eyes.

Before the war began, the Times' Op-Ed page was overcrowded with the ruminations of the so-called liberal hawks: Democrats or independents who for various reasons favored military action but sought to remain distant from George W. Bush. Perhaps never in intellectual history have the soul-searchings of such a tiny quadrant of opinion been aired so extensively and so flatulently. (Salon, let it be said, was not innocent of this offense.) At no point, amazingly, did anyone point out in the pages of the Times that the proposed invasion was illegal under the United Nations Charter and, by extension, the U.S. Constitution. (Under Article VI, section 2, of the Constitution, international treaties ratified by the United States, such as the U.N. Charter, are "the supreme law of the land.")

It seems clear that the Times, like the rest of American society, isn't interested in international law because there's no precedent for our taking it seriously. Philosophically, Friel and Falk make a potent argument about the corruption of our empire -- we're violating the explicit dictates of our own Constitution -- but on a practical level it's hard to imagine what can be done about it.

During the Cold War, realpolitik dictated that the U.S. government acted in its own interests, ignoring international law; the Soviets sure weren't going to abide by it. In the post-Cold War period of American global dominance, there's been no global power structure even remotely capable of making the United States play by the so-called rules. The United Nations didn't even pretend it could do anything except stand on the sidelines and wail while Bush and Tony Blair started their illegal (and undeclared) war.

Even without embracing some utopian vision of international law, it might be possible for America's leading newspaper to view the policies and actions of its own government with a touch more skepticism (as it did, to its eternal honor, when publishing the Pentagon Papers in 1971). Even if Friel and Falk sometimes state their case too broadly, I think they're right that the Times' "misguided go-along patriotism," especially in the wake of September 2001, has led to an "imbalance of knowledge" between the United States and the world. Most newspaper readers in other countries were aware that the proposed invasion of Iraq was illegal and that the WMD (and al-Qaida) charges leveled against Saddam Hussein were speculative at best. As of Nov. 2, at least, Americans still hadn't gotten the memo.

In fairness, the Times' coverage of the Iraq conflict has turned sharply critical since it became clear how badly Miller and her editors got played on the WMD story. And herein lies the difference between the Blair and Miller cases. Jayson Blair was essentially a lone sociopath whose supervision was so lax that he broke every accepted code of journalism and got away with it, at least for a while. Judith Miller played by the rules, at least as they were understood at the Times in that moment. She presumably believed that the supposed Iraqi defectors supplied to her by Ahmed Chalabi -- head of the Iraqi National Congress and one-time neocon fave-rave -- were genuine, and in their eagerness for front-page scoops, Raines and other editors accepted the stories on blind faith.

When the Times ultimately disavowed Miller's WMD reporting -- which did not happen until May 26, 2004, more than a year after the last of her controversial pieces -- it did so in restrained, rather technical language, in an unsigned editorial on page A10 that was reportedly written by Bill Keller, who had himself been a pro-war "liberal hawk." No reporters or editors were named, although the pieces discussed were mostly Miller's. Perhaps it was dignified not to cast aspersions directly on the departed Raines, but the piece, unsurprisingly, also did not discuss the notion that the Times was overly eager to balance its liberal reputation by uncritically embracing whatever the government said was true.

Keller's editorial made clear that the Times had been hoodwinked by Chalabi (who had recently been removed from the U.S. payroll and even accused of spying for Iran). It did not say that the whole enterprise resulting in Miller's breathless exclusives might have been a dark propaganda operation, planned by Paul Wolfowitz at the Pentagon and funded by American taxpayers. As Friel and Falk detail, Chalabi and the INC had received funding from the Defense Department, under the Iraq Liberation Act of 1998, to supply Iraqi defectors to U.S. intelligence agencies and then to Western reporters.

A subsequent assessment by the Defense Intelligence Agency, as has been widely reported, found the information supplied by Chalabi's defectors to be "of little or no use." This introduces the hair-raising possibility that the Pentagon spread Chalabi's WMD disinformation to journalists while knowing it wasn't true -- or simply not caring whether it was or not. "It seems that Chalabi may have been paid by the U.S. government," Friel and Falk write, "to give what was known to be false or suspect information to the Times about Iraqi WMD at critical moments that supported the work of the Pentagon's Office of Special Plans," the Wolfowitz unit that coordinated strategy for the Iraq invasion.

Looking too closely into the Miller affair, then, would raise the question of how America's leading newspaper, which prides itself on its impartiality and its "non-crusading" character, was so readily hypnotized by a mendacious administration that it splashed that government's most spectacular untruths across the front page, over and over again. This question goes well beyond Judith Miller or Howell Raines or Bill Keller, all of whom have to look in the mirror every day and wonder to what extent they are responsible for a misguided war that has cost thousands of human lives and now feels like a bottomless disaster. Jayson Blair was just a weird kid who told some fibs.

It's easy for a book reviewer to sit here and second-guess the Times' reporting on Iraq long after the fact. The individual who bears ultimate responsibility for the Iraq war is George W. Bush, and he might well have gone ahead with his long-desired invasion if the Times had never swallowed any of Chalabi and Wolfowitz's bunkum (and, for that matter, if 9/11 had never happened). Of course, you or I didn't know that when Colin Powell gave his fateful audiovisual presentation to the United Nations in February 2003, he was pretty much pulling it out of his butt. Almost every reporter has been hoodwinked by a source and, if he or she is honest, can imagine being swept up in scoop-fever to the point of making Miller's mistakes, egregious as they were.

No, the fundamental question about the future of the New York Times, in the Keller era and beyond, is whether it can recover a sense of true impartiality and independence, or whether its editors and managers have become so snuggly with power, so seduced by the corroded political discourse of our time, that they define "impartiality" as a point of perpetual, semi-neutral waffledom, halfway across the infinitesimal distance between Joe Lieberman and John McCain.

Friel and Falk quote from the legendary opinion of late Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black in the 1971 Pentagon Papers case, when the court ruled that the Times could publish the leaked documents in defiance of the Nixon White House: "In the First Amendment, the Founding Fathers gave the free press the protection it must have to fulfill its essential role in our democracy," Black wrote. "Only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government. And paramount among the responsibilities of a free press is the duty to prevent any part of the government from deceiving the people and sending them off to distant lands to die of foreign fevers and foreign shot and shell."

Seen in this light, the Jayson Blair case was an embarrassing sideshow, nothing more. With the bogus WMD stories reported by Miller and approved by various editors, the Times -- which, for all its flaws, remains the last, best hope for American journalism -- disgraced itself and betrayed its essential role in what remains of our democracy. We have to hope that Bill Keller, Arthur Sulzberger Jr. and about 1,200 other people who work on 43rd Street understand that.

Shares