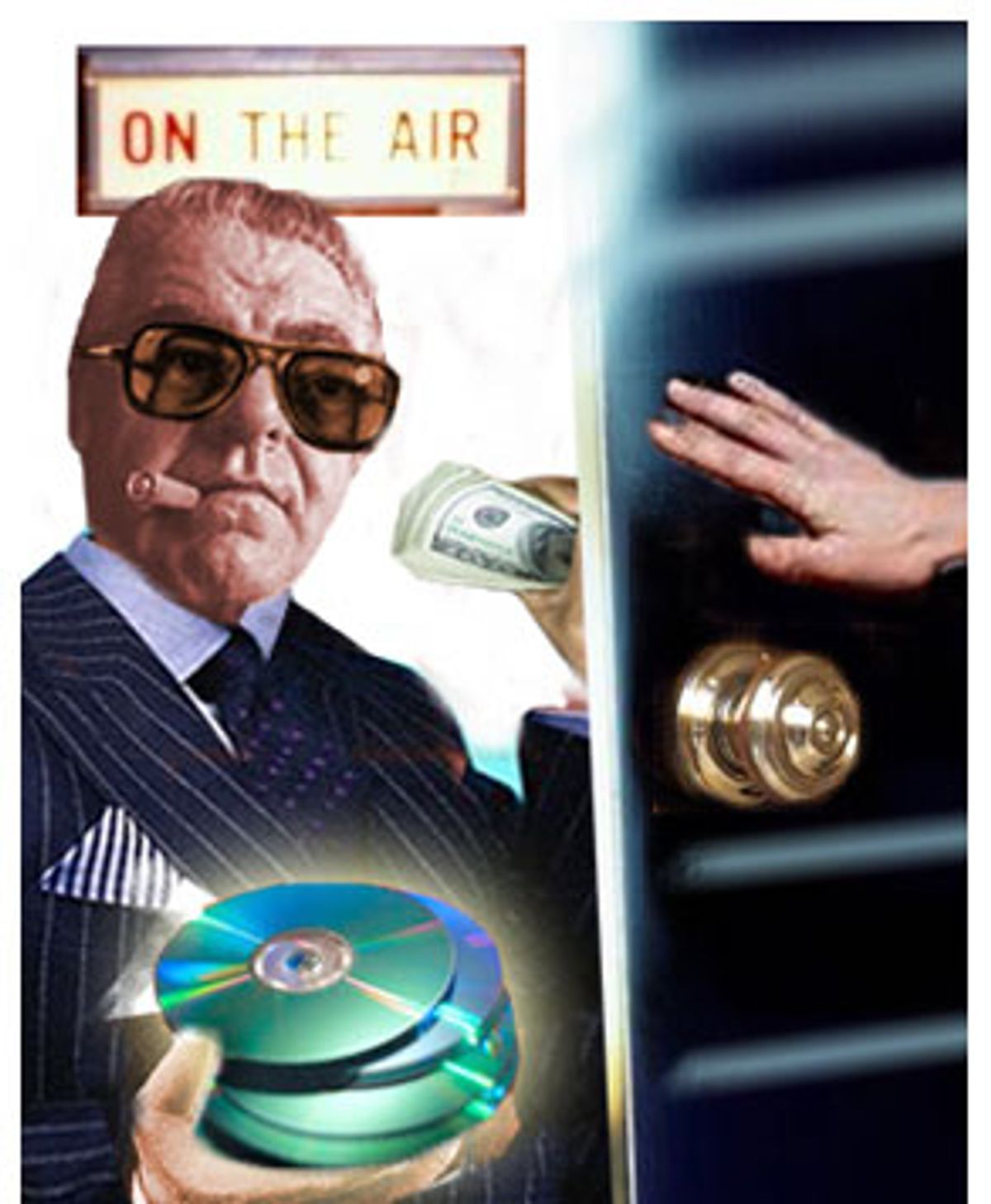

The new year brings some good news for artists, record companies and music fans. Independent promotion, the entrenched system by which record companies pay middlemen to get songs played on FM stations, has finally been reined in. It's the practice that's sucked hundreds of millions of dollars from the pockets of labels and artists, been tagged by critics as nothing more than legalized bribery, while helping dumb down radio playlists.

"Ding-dong the witch is dead," crows one record company executive, who, like most people contacted for this article, agreed to talk only on the condition of anonymity. (The indie system may be going down but the topic remains sensitive inside record companies, where neither executives nor artists want to jeopardize potential radio airplay because of public statements.)

Under pressure from New York's nosy attorney general, who has already posted an impressive track record weeding out corporate fraud in other major industries, the system is finally collapsing -- or at least contracting -- from its own weight. In recent months, chain after chain of radio stations has announced it's cutting official ties with the middlemen or indies, who are now struggling to come to grips with the radically changed landscape around them. "We're not becoming millionaires anymore," says one longtime indie promoter for top 40 radio. "We're just paying our bills. I'm hoping I'll still be in business next year." They shouldn't bother looking to the record company counterparts for any sympathy, though. "Let's face it," says a label source, "the system was a scam."

The bad news for musicians and radio fans, though, is that even in the wake of the indies' demise -- a remarkable industry milestone considering how far back the look-the-other-way practice dates, and how many times labels and artists vowed, unsuccessfully, to do away with the system -- tight radio playlists are unlikely to improve anytime soon. While indie promoters are often seen as dubious, they did have a knack for getting new acts their break on FM radio. That's why some industry insiders worry that station programmers may soon become even less adventurous in choosing which songs get tapped for rotation on FM stations' heavily guarded playlists.

The indie promotion fallout could be especially tough on smaller, independently owned record labels, the very outlets many assumed would benefit if the costly radio promotion system ever collapsed. "It seems counterintuitive, but the weakening of indie promotion is not a good thing," says the owner of a small, successful label. "It further cements the hegemony of the major labels and will definitely narrow what's heard on the radio. The short-term effect is not good for independent music."

The issue of pay-for-play radio promotion has been a flashpoint for years as rumors of bribery, kickback and even ties to organized crime have attracted periodic press attention as well as a handful of mostly futile criminal investigations. In 2001, Salon helped pull the curtain back further with a series of articles detailing how indie promoters had transformed themselves into extraordinarily powerful and lucrative gatekeepers, paid outlandish fees for services that were often dubious at best and whose results -- radio airplay -- were almost always impossible to quantify.

As one major-label V.P. told Salon at the time, "It's nothing but bullshit and operators and wasted money. But it's very intricate, and the system has been laid down for years."

From a business standpoint, it never made much sense: Why vest so much power and pay so much money to outside sources who did so little work? But for decades, indie promotion thrived in the smoke-and-mirrors economics of the music industry. Radio station owners liked it because indies were paying them annual fees up to $400,000 to work with that station exclusively. Indies loved it because once they aligned themselves with specific stations they could turn around and bill record companies every time a new song was added to that station's playlist. And labels, while cringing at the indie fees, felt a certain sense of security knowing they'd paid all the top indies, hoping that would translate into hit records. "The system was driven out of fear," says one regional record company radio promoter. "It was used as an insurance policy." Like an insurance policy, you might never need it but it's nice to know it's there. The same went for indies and the possible strings they could pull at radio.

"Everyone tolerated payola when you were getting something in return," notes Jenny Toomey, executive director of the Future of Music Coalition, a musician advocacy group. "The problem with indie promotion, combined with increased ownership consolidation and fewer slots on the radio playlists, was labels were paying more and more money and not getting anything in return. It became untenable."

Dating back to the earliest days of rock 'n' roll, record companies have been trying to win favor at radio stations. The challenge is there have always been too many radio stations nationwide for record company staffers to keep close tabs on. So they hired indies, people with close business relationships in different markets.

Indies were paid to pester programmers, take them to lunch, set them up with concert tickets, and help them land hot bands for exclusive station promotions. Indies were usually paid on a per-project, or per-song basis, earning a flat fee to work the phones on a song's behalf, and then given bonuses depending on how high the song charted. Indies acted as paid lobbyists and labels were grateful for whatever help -- real or imagined -- they provided. Labels were also careful not to make enemies with indies, knowing those same lobbying efforts could be put to use to keep a song off the air if the indies felt crossed.

The promotion system has ebbed and flowed between extremes. On the one hand, legitimate independent contractors have worked as lobbyists on behalf of record companies, schmoozing programmers in hopes of getting acts added to the playlists. During the '90s alt-rock boom, for instance, little known Offspring had indie Mike Jacobs to thank for helping get the band's '94 single "Come Out and Play" a shot on major-market FM radio, which subsequently drove the band to multiplatinum success.

But the network of indies soon evolved into an expensive phalanx of toll collectors -- some one-man shops, others with dozens of employees -- who billed record companies exorbitant fees for very little work. Frustrated labels, which helped concoct the crooked system, couldn't bring themselves to dismantle it for fear that not playing and paying might cost them crucial radio airplay.

"As much as we hated spending the money," says one label executive, "we couldn't have one label saying we're not spending indie money because the other labels will keep spending the money instead. The only way to stop was for the stations to stop taking our checks."

The issue has remained so central to the business because radio still represents the most effective way to sell records. Videos on MTV are nice, four-star reviews can soothe egos, and downloads help spread the word of mouth, but heavy rotation on FM radio is still what separates financially successful acts from struggling ones.

"A lot of great songs never saw the light of day at radio because there was no money behind them," concedes one label source. The examples are almost endless. Pick a favorite band or deserving song that's never been embraced on the FM dial; odds are there was no "push" -- no radio promotion money -- behind it at radio.

And the money connected to indie promotion in recent years was staggering, costing labels $250,000 just to pitch a song, and much more if the song became a hit. When Mercury Nashville crossed country singer Shania Twain over to pop radio in 2001, the label spent $1.5 million on indie promotion alone, according to the label's president. For record companies, indie promotion often cost more than making the actual album or marketing it. Of course, labels turned around and deducted a large portion of those promotion fees from artists' earnings. As Don Henley testified before the Senate Commerce Committee last year, "I know there's payola, because I get billed for it."

Artists are now getting billed less, thanks in part to an ambitious politician. It appears New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer's recent move to subpoena record companies for all relevant indie promotion e-mails, contracts and correspondences prompted already nervous, and cash-strapped, radio and record companies to hastily retreat from the dubious indie system that was costing labels more than $150 million annually. Spitzer's team isn't talking publicly. But they could be investigating whether labels, indies or stations broke any payola laws, which forbid broadcasters from accepting anything of value in order to get songs played, and not disclosing the quid pro quo to listeners. Or more broadly, the team could be looking at whether artists who can't afford indie fees are being locked off the airwaves, facing restraint of trade.

The decision late last year by radio giant Infinity Broadcasting and its 100-plus music stations to cut ties with indies was just the most recent in a stream of capitulations, as questions of undue, or even illegal, influence hovered around the pay-for-play system.

"Spitzer says I'm going to look into this and everybody's folding like a house of cards," marvels one appreciative label executive. "We needed an outsider to come in and say this is bullshit and this is illegal. If [Spitzer] came out of nowhere and said he was going to investigate, it would have raised some eyebrows with a chuckle; 'Good luck, buddy.' The fact is he's nailed the accounting industry, Enron, and now he's after the insurance company for fraud. This is the real deal."

Looking back, the beginning of the end for indies actually came in June 2002 when radio giant Clear Channel ousted Randy Michaels as the head of its mammoth radio division. A flamboyant manager, and former morning shock jock, Michaels moved aggressively in the wake of late '90s industry consolidation to leverage Clear Channel's huge station roster list of 1,200 stations by pressing record companies to pay indies more and more for airplay. (By 2000, it became virtually impossible to have a pop, rock, country or R&B radio hit without its being played on Clear Channel stations.) By working with just a handful of indies, who in turn dramatically increased their fees to record companies, Michaels and Clear Channel helped drive up dramatically the cost of radio promotion.

"Clear Channel got greedy," says one label promotion veteran. "When Randy Michaels ran the company, he saw the record labels as Chase and Citibank -- he wanted every cent we had. The numbers got crazy. So what happened? The top label guys got together and said enough. They went to [Michaels' boss] and said, 'This is what's going on. It's extortion.' Clear Channel fired Randy Michaels and then got rid of the indies."

That came during the spring of 2003. Yet Clear Channel didn't suddenly sprout a moral conscience. Under increasing pressure from Capitol Hill for allegations that it was abusing its consolidated power, and with more and more legislators openly discussing the need to address the abuses of pay-for-play, Clear Channel announced that it would end all exclusive contracts with indie promoters. The company simply could not afford the bad P.R. of trying to defend the pay-for-play system. "You're not going to get [Clear Channel CEO] Lowry Mays to appear before the Senate trying to defend pay-for-play and make it sound OK," says a record company executive. "It might be legal, but just barely and it's basically indefensible."

Last November it was Viacom-owned Infinity's turn to walk away from indies. As with Clear Channel's 2003 announcement, there's a feeling that politics had more to do with Infinity's move than genuine concern about the ethics of radio programming. "Viacom's corporate business is selling TV advertising and Infinity's just one part of a gigantic company and one that has experienced controversy [with Janet Jackson's Super Bowl halftime show]. I don't think they wanted another drama," says a record company president.

While many industry insiders are toasting the demise of the corrupt system, others are not yet raising their glasses, pointing out that indies have long been remarkably resilient. Back in 1981, upset about the influence amassed by a group of powerful indies known as the Network and costing record companies approximately $70 million each year, the two largest labels, Warner Bros. and Columbia, tried to spearhead an indie boycott. According to Fredric Dannen's 1990 exposé "Hit Men," the pushback collapsed when labels' marquee artists, such as the Who, revolted after having trouble getting their songs on the radio. (In theory, artists were all for shedding indies, as long as the unpleasant task didn't affect their chart position.)

Four years later, wrote Dannen, "The cost of independent promotion had become suffocating. After the industry blew its chance to abolish the Network in 1981, the promoters grew more powerful than ever, and their tabs went up accordingly." Desperate, the labels suggested the Recording Industry Association of America launch an investigation into indies. That investigation was shelved but the labels got the out they needed in 1986 when NBC journalist Brian Ross, aided by key record-company sources, aired a sensational report connecting indie heavyweights with organized crime. Within days of the Feb. 24, 1986, report, major labels such as Capitol Records and MCA announced they were no longer using indies. At the same time, then-U.S. attorney in New York Rudy Giuliani launched a federal grand jury investigation into indie promotion. And in April, Sen. Al Gore, D-Tenn., announced a new Senate probe into payola.

Neither, though, amounted to much, and over time the system reemerged, with the humbled indies charging just $700, rather than $3,000, for a song added to a major-market station. That's where the base rate stayed well into the '90s. But by 2001 the fees were just as outrageous as during the peak 1980s period chronicled in "Hit Men."

It was passage of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, which drastically eased ownership limits for radio and spawned rampant consolidation, that juiced the promotion rates. Simultaneously, big-time indie firms like Jeff McClusky & Associates, which once represented just a couple dozen stations, cashed in on their long-term relationships with corporate owners and were soon doing business with hundreds of stations across the country. The ability to influence -- or at least to be seen as influencing -- so many playlists gave the indies extraordinary power, and they quickly leveraged it against record companies, jacking up their fees during the late '90s.

The indie promotion system at pop and rock radio soon evolved into an elaborate scheme where promoters were signing exclusive deals in order to "represent" certain stations, to act as a kind of middleman between the radio station and the record company. Generally, the indies paid that station an upfront annual fee, ranging from $100,000 to $400,000, depending on the station's ratings and market size. Stations were only too happy to cash those checks. Once that deal was signed and the station was "claimed," the indie was free to send out weekly invoices to record companies for every song that was added to that station's playlist.

The invoices added up. Every song added to an FM radio playlist came with a price: Roughly $800 per song in middle-size markets, $1,000 and more in larger markets, and up to about $5,000 per song for the biggest stations in the biggest markets. Most tightly controlled stations were annually adding between 150 and 200 songs to their playlists, a veritable fraction of the new songs released every year.

The beauty for the indie was that regardless of whether he had anything to do with convincing the station to play the song -- the music director may have already been a big fan of the band -- he got paid because the single was being played on his claimed station. Whereas indies were once desperate to get the songs they were hired to promote on the air, suddenly it didn't matter which songs their stations played because the indie got paid by the labels regardless. That's why indies were soon derided as opportunistic toll collectors.

And invoices for adds were just the first of many options indies had for billing labels. Another was called "spin maintenance"; if a label wanted to boost the number of times a song was getting played at certain stations, it could simply write a check to the station's indie. As one label executive concedes, "Whoever spent the most money got the most records added on radio that week." That's not how the American broadcasting business is supposed to operate. "In theory, the idea is that the industry is meritocracy; that if you're talented and work hard, you rise to the top," says Toomey at the Future of Music Coalition. In this perfect world, radio stations themselves would scout new and adventurous artists, and introduce them to listeners. "But when independent promotion limits access to the airwaves, then that's not the case," says Toomey.

Today, though, the irony is that the besieged indie system may not open the doors for new acts at commercial FM radio. Artists and their advocates had hoped that if the costly pay-for-play system were ever dismantled, it would clear the way for a broader range of acts, particularly on smaller labels, to compete for airplay without having to write six-figure checks; that radio might become something resembling a meritocracy. But some industry insiders fear the opposite will happen; that without indies working the phones on their behalf, smaller labels and their acts will have an even harder time getting the attention of major-market programmers.

"How are we going to get anybody at Clear Channel or Infinity stations to listen to our records? We can't get those programmers on the phone," says the head of one independently owned label that has produced, with the help of indies, top 10 hits in the past. "A lot of people look at indie promotion as a cancerous thing. Ultimately it's not that simple. There was a lot of corruption but there was also a legitimate function. They've been a way for independent music, if they could scrape together the money, to be on equal playing field as the majors are."

Even radio promotion veterans on staff at established, well-funded labels are concerned about getting their new acts, or "baby bands,'' on the air without the help of indies. "The good news is it will be less expensive for us to do business. The bad news is it's going to be harder to break new acts," summarizes one label promotion executive. "How are we going to get a baby band with two mid-charting singles on the radio other than just begging?"

The fear is that without indies, radio programmers, paid first and foremost to secure high ratings for stations that in some markets now carry price tags in excess of $100 million, will rely more and more on proven hit singles as well as older, already-familiar songs, leaving less airtime for new acts. "Radio stations don't get ratings through playing a lot of new music, they get ratings through repetition and familiarity," says one indie veteran. "You think Infinity [in the wake of its indie ban] will all of a sudden say, 'Hey, let's play lots of new music!'? It doesn't work that way. I think the playlists will get tighter."

Already facing a shrinking audience, as fans of new and adventurous music continue to flee radio in search of freewheeling -- and commercial-free -- alternatives like the Internet and satellite radio to hear their favorite artists, pop music stations, with their increasingly tight playlists, may finally be writing their own doom. If so, this time indies won't be around to take the blame.

Shares