Most people with a passing knowledge of the history of the personal computer are aware that Apple founder Steve Jobs is famous for his "reality distortion field": his ability not only to deny objective fact but also to convince anyone within his reach that black equals white and yes is no. But how many have heard this advice on how to deal with Jobsian rhetoric?

"Well, just because he tells you something is awful or great, it doesn't necessarily mean he'll feel that way tomorrow," software manager Bud Tribble tells Andy Hertzfeld, a leading member of the team that designed and built the first Macintosh computer. "You have to low-pass filter his input."

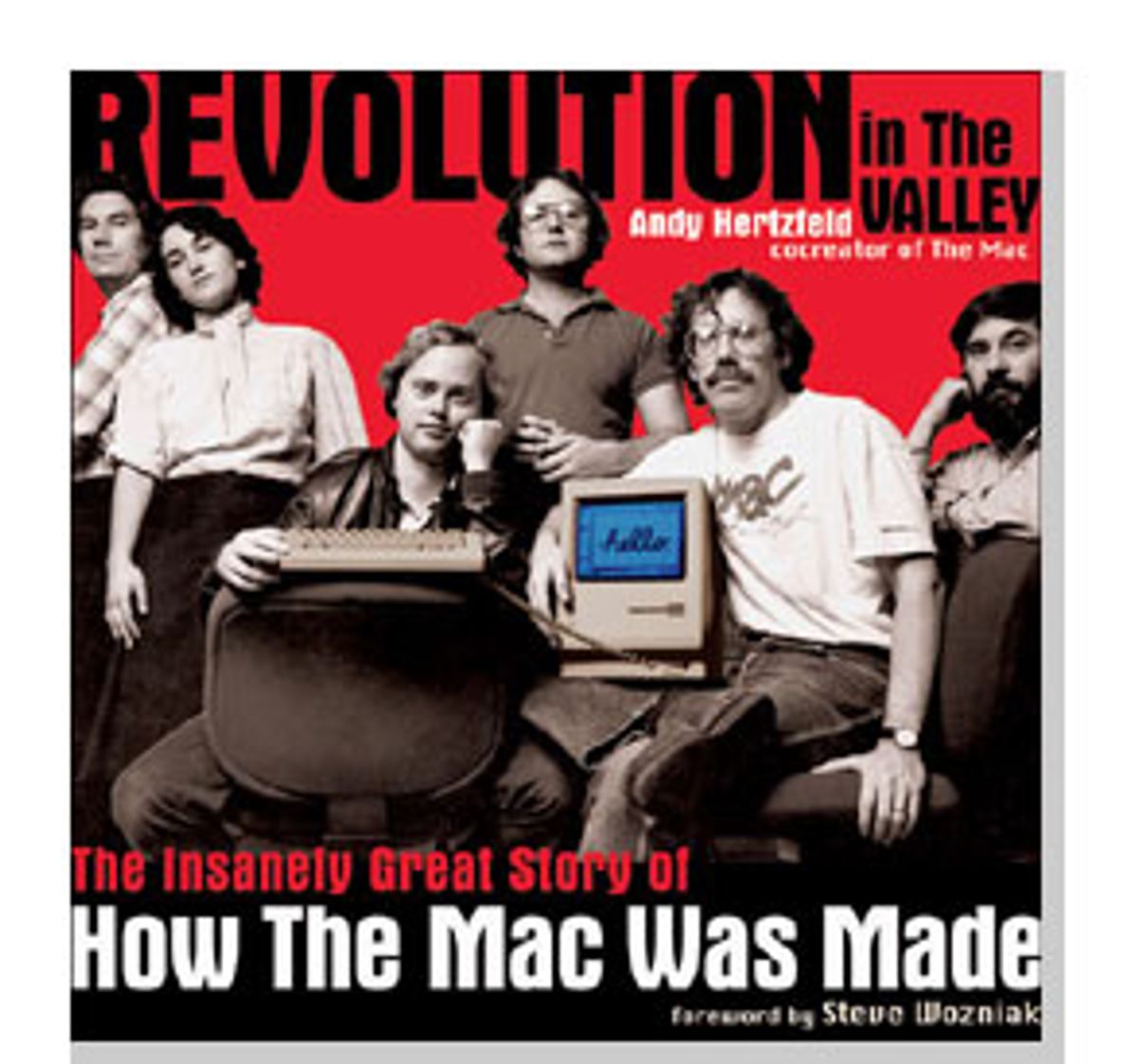

In "Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made," Hertzfeld's collection of tales about the birth of the Macintosh, the story that contains this anecdote continues merrily, making no attempt to define for the lay reader what the term "low-pass filter" means. You can guess, or you can do what I did and Google it. And learn that if one is dealing with, say, the radio spectrum, a low-pass filter cuts out high-frequency waves, allowing only low-frequency waves to pass. This can be useful in cases where the high-frequency waves are likely to introduce random errors into whatever is being broadcast. So, in other words, when listening to Jobs, ignore all the times when he says something is "great" or "awful" -- the highs -- and just try to focus on the gist -- the low.

It is to the credit of Hertzfeld and his editors at O'Reilly, a noted publisher of computer trade books that has been moving aggressively into more mainstream markets over the past half decade, that the stories in "Revolution in the Valley" are never dumbed down. There are plenty of computer history books in which every arcane detail has been unpacked and elucidated for a mainstream audience. There's clearly a place for those books, but by translating geek-speak they put up a barrier between the reader and the real world of the programmers and hardware engineers who built these amazing devices.

Reading "Revolution in the Valley," you may feel as though you're sitting in a bar listening to engineers swap stories. You may not understand every word, but you know you're getting the real thing, and that has value. It is, for example, fascinating to look at some of the illustrations in this lovingly produced book and realize that they are photocopies of to-do lists made at the time by the creators of the Mac. For most people, a to-do list is an ephemeral thing, something that gets crumpled and tossed away when the items are checked off. But for Hertzfeld, these lists are clearly priceless documents of history, and given how the Mac brought computing to the mainstream, he is right.

The "for the geeks, by the geeks" strategy works. For a true Macintosh aficionado, this is a must-have, an essential cornerstone of the Mac library. For the reader who is merely interested, there are enough nuggets about Jobs and Bill Gates and the sui generis lifestyle of a passionate programmer who thinks nothing of working 90 hours a week to make up for the book's opaque disquisitions on computer memory management.

The result is something that reeks of honesty. Journalists have a tendency to force things together to fit their grand narratives, to pick and choose among the facts and stories and people available to find a way to tell the "best" story possible. But when the people involved tell their own story, sure, there may be repetition and overlap, there may be places where the story line breaks down, and there may be plenty of unanswered questions at the end. But beyond all that, you are left with the unmistakable feeling this is how it really happened. This is how the Mac was made.

As I write this review, the annual gathering of the Macintosh tribes, Macworld, is just getting under way, and the usual computer press frenzy is boiling. What will be the big announcement this year? A $400 computer? An even cheaper, smaller, cooler iPod? Something new, something breathtaking? The hype, especially since Jobs' triumphant return to the company that he started and then was exiled from, has always been nonstop. Outside of, possibly, Microsoft, no computer company has received more press in the past 25 years than Apple. The story of the Mac has been told time and time again. Does it really need to be told once more?

I wondered about this question before diving into "Revolution in the Valley." But at the end, which occurs approximately at the moment when former Pepsi executive John Sculley forces Jobs out of his own company, I realized there are some stories that can't be told enough times.

As we sit staring at our multiple-windowed computer screens, effortlessly switching between e-mail and word processing and the Web and games and spreadsheets, it may be hard to recall that it really wasn't so long ago that personal computers were clunky devices accessible only through arcane instructions typed into a command line. Your blood had to run at least half-geek to take pleasure in such machines -- or to get any kind of useful work out of them. Perhaps the most amusing irony in "Revolution in the Valley" is that while it is a book by geeks for geeks, it is about the making of the computer that brought computing to nongeeks.

Hertzfeld and his co-conspirators, hardware whiz Burrell Smith, software magician Bill Atkinson, visionaries Jef Raskin and of course Jobs, and a handful of others, should not get sole credit for making computers user-friendly. They took ideas from elsewhere -- not least the famed Xerox PARC laboratory -- and built on the efforts of countless other engineers and programmers. But if there is a moment when the computer became something that was for the world, it was that moment when the Mac was born, and even those of us who use PCs should be grateful to this day.

And in a world of ceaseless hype, we can even give Hertzfeld the benefit of the doubt and believe him when he closes his collection of tales by saying that in contrast to every other computer, "the Macintosh was driven more by artistic values, oblivious to competition, where the goal was to be transcendently brilliant and insanely great."

Shares