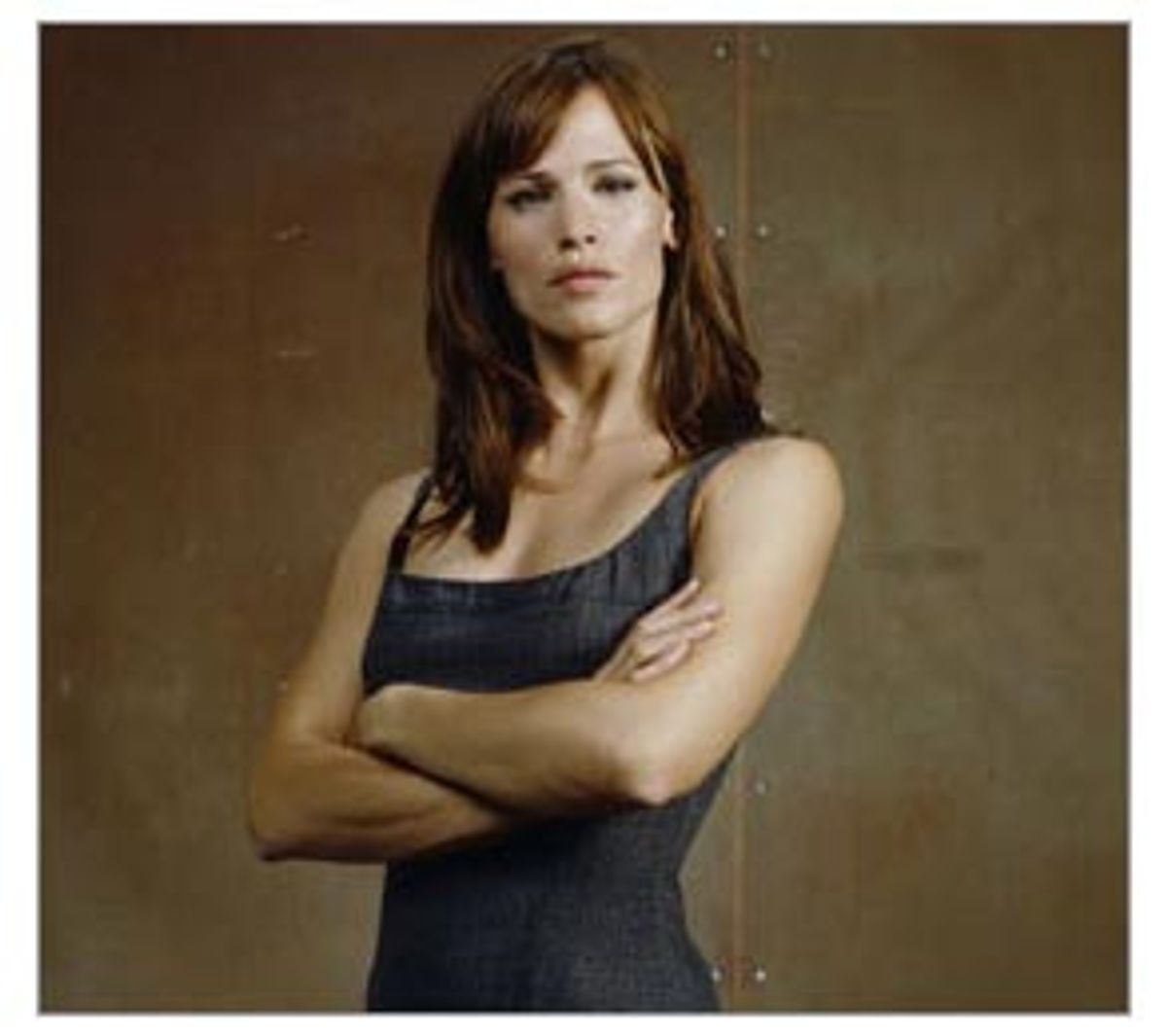

Enough time has passed for it to become apparent that Tolstoy was wrong -- it's all unhappy families that are alike. J.J. Abrams must have realized something like that when he set out to create "Alias" (Wednesdays at 9 p.m. EST on ABC). Beyond its obvious reference to the panoply of funky disguises worn by its heroine, CIA agent Sydney Bristow (Jennifer Garner), the title is a clue that the show is pretending to be something other than it is.

I first tried watching "Alias" when it premiered in the fall of 2001. I was looking for something like the mod, gadget-laden spy movies and TV shows I loved as a kid. Despite the moments when the show was what I expected it to be -- Sydney on some mission strutting into a club/hotel/casino in whole runway seasons' worth of chic outfits -- "Alias" struck me as pedestrian. Too little gadgetry and too much family and workplace drama. That's exactly the point.

To treat "Alias" as if it were about nothing other than Garner's costume changes, or as though it were some spy-girl fantasy for comic-sated fanboy geeks, is to miss the wit and emotion and twisty narrative pleasure it offers.

Yes, it's a spy drama. And its action sequences -- like last week's fourth-season opener, in which Sydney dangles by a fraying strap from the open door of a speeding train zooming over a bridge -- are shot and edited with a terse precision that's almost entirely missing from the largely incoherent action sequences of mainstream movies. But for all its excitement and cliffhangers, the show is at heart the story of the dysfunctional Bristow family: Sydney and her father and fellow agent, Jack, played with impeccable slyness by Victor Garber, and, in the second season, Sydney's mother, the eminently untrustworthy former KGB mole Irina Derevko (Lena Olin).

Abrams isn't interested in using the espionage genre as geopolitical social commentary, as "24" does. That show, after a terrible third season, seems, at least judging from its first few hours, to be back on course. Abrams wouldn't write a scene whose implications are as unsettling as the one in this year's "24" opener, when a pleasant suburban family of Turkish immigrants sits around the breakfast table discussing the terrorist attack they're launching later that day. The baddies come and go on "Alias," their plans defused before they reach the potentially apocalyptic level. There is overarching -- and intermittent -- mumbo jumbo having to do with the prophecies and inventions of an inventor named Milo Rambaldi, but that's purely the show's McGuffin.

Abrams uses the spy genre, with its shifting identities and loyalties and motives and sudden betrayals, as a reflection of the thorniness of family relationships, in which conflicting loyalties can feel like betrayals. "Alias" is far from the gray depressiveness of John le Carré's tales of the spy as dogged civil servant. Abrams' sensibility is American, pop-inflected and quicksilver.

That partly explains why Sydney isn't Emma Peel or Modesty Blaise, characters too Continental to suit Abrams' conception. Sydney is the spy as perennial good girl, the straight-A student, the one voted both most popular and nicest. That's the joke beneath all of her costume changes -- she always looks like Sydney. This part of the show has a nice sense of play, the suggestion of a girl on perennial trick-or-treat. When Sydney dons some new guise to con information out of her target, it's less fess up than dress up.

Her entrance in last week's season opener, in a short blond bob and a baby-doll nightie with push-up brassiere, was the closest the show has ever let the character come to being a sexpot. And the effect was defused almost immediately when she approached the Eastern European scientist she had targeted and announced in an outrageous Scandinavian accent, "I am for sleeping now." (I thought of the bit at the beginning of the second "Charlie's Angels" movie where Cameron Diaz enters some Siberian hellhole swathed in white fur and asks, "Thees ess hostel, yah?")

As Garner has played the character -- and that's superbly, a mixture of steeliness and impetuousness -- Sydney has traveled from a cusp-of-adulthood coltishness to something more confident. She's not jaded or cynical, but like other great pop-culture characters we've followed over a period of time, like Buffy or Harry Potter, Sydney has toughened up with experience. The scene in last week's episode where she was interrogated by a no-nonsense agency chief played by Angela Bassett captured Sydney's quick, confident, impatient sharpness. Standing up to an actor as commanding as Bassett is a test for any performer. It's a measure of how good Garner is that she did it without breaking a sweat, and a measure of how much we've come to believe in the character of Sydney that we didn't question the insubordination.

You'd be hard-pressed to find a character on television who has undergone a harder "one damn thing after another" trial by fire than Sydney Bristow. The series opened with Sydney juggling grad school with a job in international banking. The job was a cover for her work with SD-6, which she believed to be a supersecret section of the CIA.

After she confesses her job to her fiancé and her boss, Arvin Sloane (Ron Rifkin), has him killed, Sydney discovers that SD-6 is not part of the CIA but the exact sort of criminal syndicate she believed herself to be working against. When Sloane orders that Sydney be killed as well, she's rescued by her estranged father, Jack, and finds out that instead of being a globetrotting businessman, he is also an SD-6 agent. The difference between them is that Jack knows the truth about SD-6, has made Sloane believe he shares his evil goals, but is in fact working as a CIA mole to bring down Sloane. Sydney spills all she knows about SD-6 to the CIA and, now a mole like her father, goes back to work for Sloane, having sworn revenge on him.

And that, folks, was just the first two hours of the series. "Alias" is yet more proof that the best television series have all but abandoned self-contained week-to-week episodes in favor of sprawling novelistic narratives. (I caught up on "Alias" over the summer after being knocked out by Garner's performance in "13 Going on 30," bingeing on the first three seasons as if I were reading a long, satisfying novel.)

Even among those shows, "Alias" is noteworthy for the way it has played with the premises it has established. Like Joss Whedon, Abrams is a pop-culture genius who operates right on the line dividing confidence from recklessness. Having established the premise of Sydney as mole at SD-6, Abrams blithely threw out that premise midway through the second season by having the CIA raid SD-6 and shut down the organization, and sending Sydney and Jack to work for the CIA proper. Last week, Abrams flipped the series yet again, sending Sydney and Jack and most of the show's secondary characters to work for an actual secret section of the CIA. Sydney is now back exactly where she was at the beginning of the first season, pretending to have a job in international banking while actually working as a spy.

But for all the pleasure of those narrative flips, the meat of "Alias" is in the more quotidian stuff. The heart of the show is the relationship between Sydney and Jack, a relationship that begins in estrangement and ventures into something approaching a conventional father-daughter relationship. That is to say, strong protective feelings from Jack butt heads with Sydney's contradictory desire for his protection and her wish to be thought of as an independent, competent adult. Any only child (which Sydney is -- kind of) will recognize that dance. You don't have to be an only child, though, to recognize Victor Garber's beady-eyed glint, which is simultaneously uproarious and frightening. Jack plays snarling papa bear to anyone who would jeopardize Sydney. To her he's some combination of Zen master, drill sergeant and oracle.

Some of the show's best moments, funny in a way that at first makes you gasp with shock, are when Jack resorts to violence to protect Sydney. Garber has worked primarily on the stage and intermittently in movies. (He was the only believable character in "Titanic.") Jack Bristow is the best role he has ever had. There's no actor on TV (and few in the movies right now) who can match Garber's particular brand of wit. Deadpan doesn't begin to capture it. Subterranean is closer to the mark. His performance is so quietly tempered that he makes you feel as if you should incline close to hear him -- which is just what Jack Bristow wants to do to put you within his claws' reaches. You never catch Garber winking to the audience. You just feel his comfort indulging in the darkest sort of humor -- and the fiercest kind of portrayal of parental love, one utterly lacking in sentiment.

It would require a blow-by-blow description of the turns the plot of "Alias" has taken over the past three seasons to capture all the nuances between Jack and Sidney. The constant is Sidney discovering some information that Jack, in the great tradition of parents of only children, has tried to keep from her; rejecting him because of it; then coming to realize his reasons for doing what he did. And that's where the resonance of the spy metaphor really comes to life. The nature of spying is that of secrets being revealed. Sydney, because of what she does, is put in the position of constantly experiencing the shock we all do when we discover something heretofore hidden about our parents -- and in the position of having to integrate that information into her picture of her father, working to accept him as a flawed human being, which of course means accepting her own adulthood.

It's not just the personal relationships that ring true in "Alias" but the workplace relationships. Get beyond the "Get Smart" façades for the various SD-6 and CIA workplaces "Alias" has shown us, and what you see looks a lot like the glass-walled, cubicled divides of any corporate office. And here, too, the spy metaphor proves potent, working as a metaphor for how jobs have come to consume our lives, to define us. In Sydney's case, her job isn't something she can leave behind because it requires her to keep up a masquerade in every area of her life outside work. And within the workplace she can't let her guard down.

Even when SD-6 got taken down, "Alias" couldn't let go of Ron Rifkin's terrific portrayal of Arvin Sloane. He's back now as a CIA consultant, a neat joke on the fact that there's no bastard bad enough for U.S. intelligence to keep from making common cause with. Sloane is the essence of the boss you wouldn't turn your back on, and I'm betting he strikes a chord even among watchers of "Alias" who don't work for evil geniuses.

Sloane gives himself away as untrustworthy when, as many bosses do, he talks about how he thinks of his co-workers as "family." (Those bosses are the ones who'll stab you in the back most viciously.) Sloane is a master businessman because he has learned to fake sincerity and warmth -- which is the most valuable asset for someone who wants to keep his motives hidden. Abrams has been generous enough to have allowed Rifkin some moments of real, open emotion in the scenes in the first two seasons with his wife, beautifully played by Amy Irving. But it's the fact that his motives are nearly unreadable, even when you know not to trust him, that makes Sloane not only a great villain but pop culture's current definitive personification of the boss from hell.

There are lots of other performances that have made "Alias" such a pleasure: Michael Vartan as Sydney's co-worker and lover, Vaughan; the wonderful Kevin Weisman as the CIA's techno übergeek, Marshall; and in the first couple of seasons, Bradley Cooper as Sydney's best friend, Will, and Merrin Dungey as her roommate, Francie, whose fate was perhaps the most baroque the show has come up with. And it has attracted an amazing gaggle of guest stars, among them Lena Olin, Isabella Rossellini, John Hannah, Quentin Tarantino, Faye Dunaway, Ricky Gervaise and Terry O'Quinn, who, after decades of sensational but unnoticed work, is finally getting the attention he deserves on the new Abrams hit "Lost."

But it's Garner's portrayal that's at the center of "Alias." Butt-kicking women have become a dime a dozen in pop culture, and tough and tender isn't an especially fresh combination (which isn't to say it can't still be a winning one). Garner's portrayal of Sydney brings a sweetness to the spy genre that it has never had. When Sydney reaches into her bag of tricks, it's not the hidden bad girl she's giving license to play, it's the good girl she is at heart, the one who wants to hand in that A paper, neatly typed and with no spelling mistakes. It's not to slight the way Garner can melt you in her dramatic scenes or the intensity of her emotional duets with Victor Garber to say that something about Sydney Bristow suggests what Mary Richards might have been as a spy. When she's going up against the baddies of the world, or even the traitors in her own midst, you have complete confidence in her. She might just break them after all.

Shares