Florida Democrats' decision to unanimously back Howard Dean as the new chairman of the DNC (Democratic National Committee) shows two things: first, there are still some Democrats out there -- including in the supposedly hopeless South -- who have brains and guts and aren't afraid to think for themselves; and second, Dean now has a real shot at winning the DNC job and launching a much-needed makeover of the Democratic Party.

Political and media elites in Washington are at once horrified and dismissive of Dean's quest. They insist that Democrats would be crazy to pick a raving liberal like Dean as their next party chairman. But as is so often the case, this inside-the-Beltway conventional wisdom is based on dubious "facts" and assumptions about how ordinary Americans relate to politics. Dean is exactly the leader Democrats need to become relevant again.

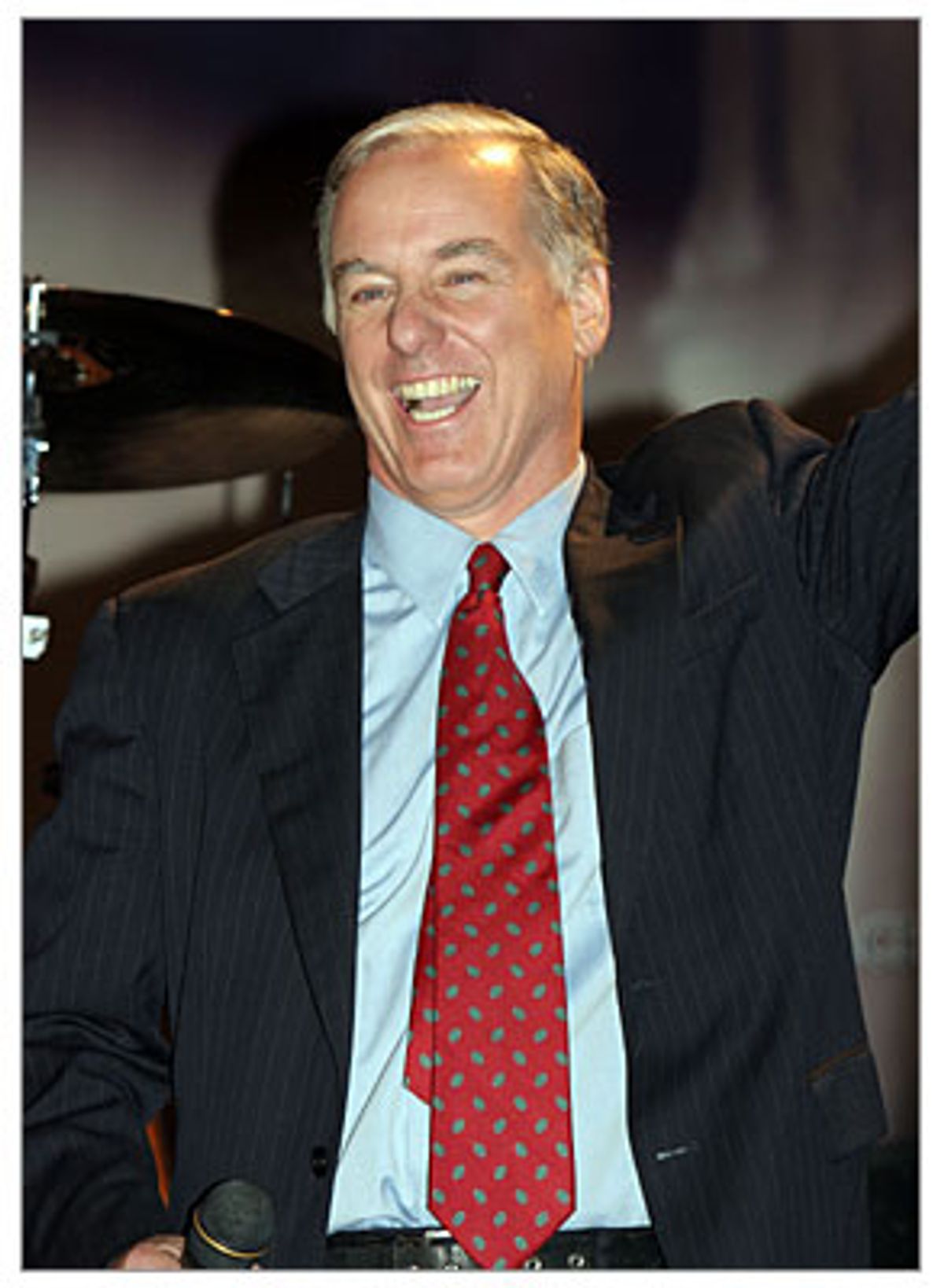

The Florida Democratic chairman's statement to the New York Times reveals just how out of touch the Washington establishment is: "I'm a gun-owning pickup-truck driver and I have a bulldog named Lockjaw," said Scott Maddox. "I am a Southern chairman of a Southern state, and I am perfectly comfortable with Howard Dean as DNC chair."

And the reason Florida Democrats like Dean?

"What our party needs right now is energy, enthusiasm and a willingness to do things differently," Maddox added. "I think Howard Dean brings all three of those things to the party."

Maddox isn't the only prominent Southern Democrat backing Dean. On Tuesday, the state chairman from Mississippi and the vice chairmen from Oklahoma and Utah announced that they too were endorsing the former Vermont governor, leading ABC News' influential The Note to declare that Dean "is now emphatically the front-runner" for the DNC job.

A year ago, Dean was jeered off the national stage by television's nonstop coverage of his "scream" speech. And it must be admitted that he showed some undeniable weaknesses as a presidential candidate in 2004, including a tendency to speak first and think later. But Dean is running for party chairman now, not president. The chairman's job is to rally and organize the party faithful to do the unglamorous but vital grass-roots work that will expand the Democratic base, reach out to new and uncommitted voters, and win future elections. As Maddox said, Dean fits that job description perfectly. He inspires grass-roots enthusiasm and his time as governor of Vermont grants him the necessary executive and administrative skills.

What's more, in the wake of the Democrats' loss to President Bush in November, Dean's political message, and especially the way he delivers it, looks better and better.

Dean, after all, was right about the central issue of the 2004 election -- the Iraq war. Nowadays, a majority of the American public believes that attacking Iraq was a bad idea. Dean was saying this -- and being criticized for it -- in the fall of 2003.

Dean was also right when he said Democrats should be the party not only of urban liberals but of "guys with Confederate flags in their pickup trucks," another comment he was derided for. But in view of how many centrist voters chose President Bush over John Kerry, even though Kerry's economic policies would have benefited them more, Dean's call to reach out to culturally conservative voters was prescient.

Above all, Dean was right that Democrats would win only if they told voters exactly what they stood for and why. Kerry never did that, especially on Iraq, where his reluctance to call the war (and not just its prosecution) a mistake let the president off the hook on his most vulnerable issue.

By contrast, Bush never shrank from saying what he believed. Like Dean, he understood a basic fact of American politics: voters value plain-spokenness in a politician much more than agreement on specific issues. Bush was even clever enough to steal one of Dean's signature lines: "You may not always agree with me, but you'll always know where I stand."

All of the news stories reporting Dean's decision to seek the DNC chairmanship repeated the standard rap against him: He's too liberal. But that charge doesn't reflect reality so much as it reflects the Washington establishment's version of reality. Dean was labeled a liberal by the media essentially because he opposed the Iraq war. Never mind that he was also a deficit hawk who opposed gun control, gay marriage and universal healthcare, or that many conservatives later embraced his criticism of the war. In the post-Sept. 11 mood of false patriotism, the media assumed that anyone who criticized an apparently successful war had to be a liberal, and that was that.

This mischaracterization has led observers to miss the real source of Dean's appeal to a jaded electorate: He knows what he believes and he's not afraid to say it plainly enough for ordinary people to understand. His vision for Democrats is not about moving the party to the left; it's about Democrats standing for something that resonates with ordinary Americans -- a task that current party leaders have manifestly failed to achieve.

Dean believes the Democratic Party's allegiance to big donors and cautious incrementalism has alienated many of its logical voters. Alone among prominent Democrats, he recognizes that the party has little future if it cannot connect in an authentic way with the extraordinary grass-roots energy that propelled his own presidential campaign (and that later nearly got Kerry elected, despite the Kerry campaign's many shortcomings).

In 2004, Dean rewrote the rules of presidential campaigns by using the Internet and local "meet-ups" to raise small donor money. But Dean's real secret was to give supporters real influence within his campaign and thus hook them on continued political participation. The idea of meet-ups, for example, came from the grass roots, not from campaign headquarters.

The Bush campaign tapped into similar grass-roots energy among conservatives and thereby expanded Republican turnout enough to gain the president a second term. Democrats must do more of the same in the years to come, and Dean is the leader who best understands that imperative. Dean, after all, is a populist. And his populism is not the brand espoused by President Bush -- a millionaire who shills for billionaires while talking like the common man. Dean's is the real thing. Which is why Republicans privately fear him.

Another part of the media consensus on Dean is that he only wants the DNC job to grease his run for president in 2008. For his part, Dean has declared he won't run if he gets the DNC job. Of course, he could change his mind. But it's worth remembering that presidential candidate Dean always said that Democrats must first reform their party and its approach to politics if they want to win the White House.

Dean is now traveling around the country telling his supporters that remaking the Democratic Party is a long-term project that could take 20 years. His first hurdle comes on Feb. 12, when 447 largely unknown party officials from around the country will vote for the next DNC chairman. The Florida and other Southern Democrats' decision to back him will, of course, be enormously helpful to Dean's prospects, but it also figures to call forth still more "anyone but Dean" efforts from the party establishment.

Everyone agrees the Democrats have to remake themselves; they just lost to perhaps the most vulnerable incumbent in history. The DNC vote will give the first hint of how they plan to proceed. At a time when America has never needed an effective opposition party more, let us pray Democrats can rise to the challenge.

Shares