Indian programmers, working in the United States under H-1B visas, demonstrate their anti-Americanism by driving only Japanese cars, writes one poster to an Internet newsgroup. At first glance, the accusation seems like a typically unfounded generalization, the kind of spiteful, xenophobic posting made by an out-of-work engineer enraged at the people he or she blames for taking American jobs away.

Except, as N. Sivakumar writes in "Debugging Indian Computer Programmers," Indians permitted to work in the United States via H-1B visas do tend to buy and drive Japanese cars. And for good reason. If a worker residing in the U.S. under an H-1B visa loses his job, he has to leave the country immediately. This means, quite often, that he has to sell his car right away. Cars with high resale value are at a premium, and according to Sivakumar, that means Toyota Corollas and Honda Accords.

It's an intriguing twist. The buying-Japanese habits of immigrant Indians are not a sign of anti-Americanism, but instead proof of their economic vulnerability. The ironies don't stop there. In this globalized world, Japanese cars sold in the United States are often built in the U.S. as a result of incentives set up decades ago to try to protect American jobs. Meanwhile, many cars sold by American companies are built elsewhere -- in Mexico or Korea, for example -- to take advantage of cheap foreign labor.

Ah globalization, the wonders it has wrought. As Sivakumar points out, "Globalization is as American as mom and apple pie." And Sivakumar is all for it, just as he is, fundamentally, all for America, the land of opportunity. He is dismayed by the racism and bile he encounters on the Net, as well as the "dirt and dog pile" that an unknown neighbor dumps on his car's windshield every morning. But he loves the country deeply, just as he loves the country he grew up in, Sri Lanka, and the county his ancestors came from, India.

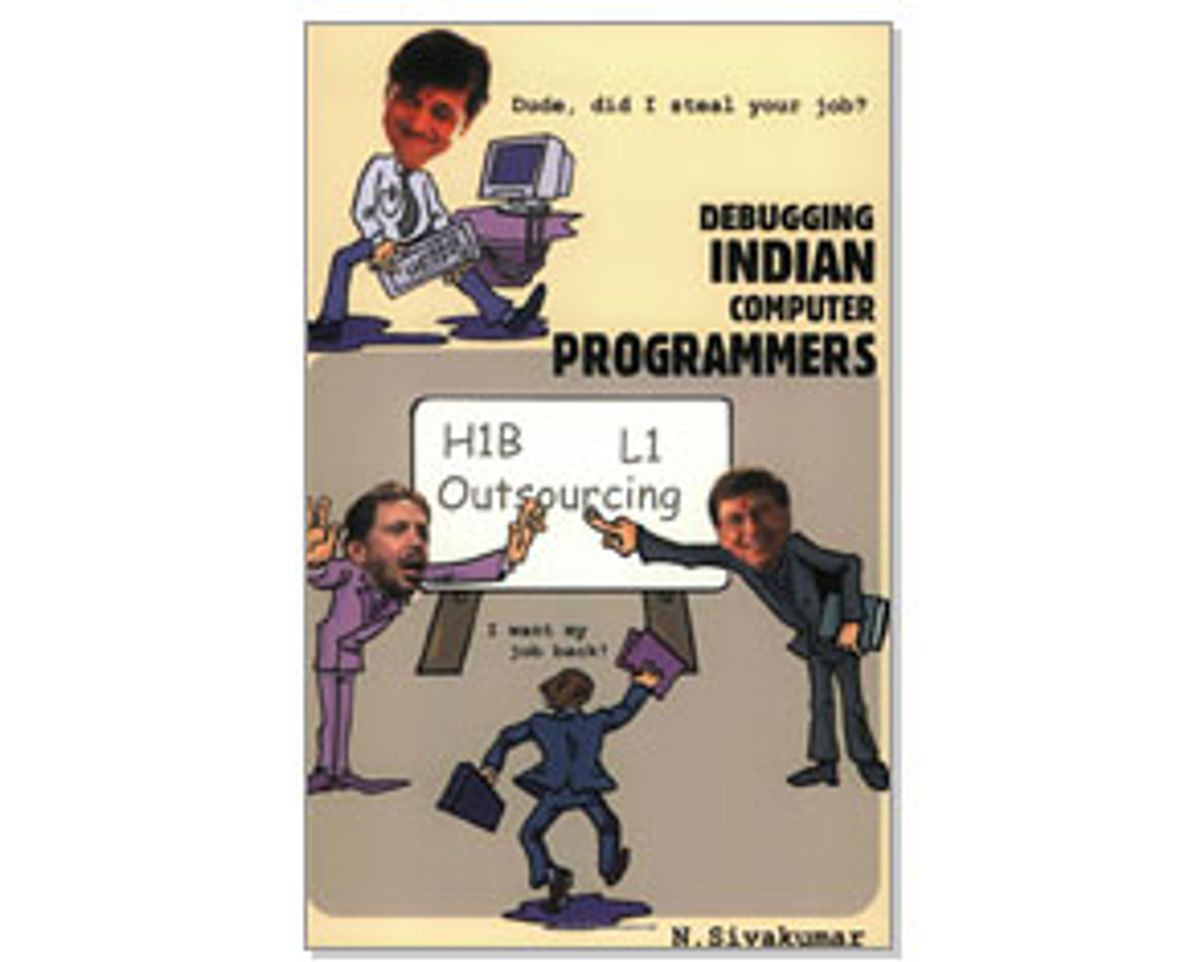

"Debugging Indian Computer Programmers" is a self-published torrent of insights and opinions about the lives of Indian programmers, the H-1B visa phenomenon, outsourcing, and America's hatred of outsiders. It is interesting not so much for the clarity of its prose and impeccable logic -- Sivakumar may be an accomplished programmer, but he isn't the greatest writer in the world -- as it is for the way it exposes to the world the mind-set and reality of the immigrant Indian programmer. Too often, in the debates about globalization and outsourcing and immigrant H-1B labor, the Indian programmer is reduced to a stereotype, a kind of faceless drone who theoretically will work harder for lower wages and who fits like a well-oiled cog into the gears of the globalized economic machine. But, of course, they're real people, with their own hopes and fears and insecurities, and the more we get to hear their side of the story, the less easy it is to define the problems of globalization as us vs. them.

Besides Sivakumar is funny. You know you're in good hands when right at the outset he notes that on his first flight to the United States he didn't know how to fasten his seatbelt. The flight attendent had to "almost hug me around my waist" to buckle it, he writes. "If it were an Indian movie, there would have been a duet song just after belt buckle process."

Sivakumar takes a touchy subject and brings both humor and fearlessness to it. He's not afraid to poke fun at the habits, and even smells, of Indian programmers -- nor is he afraid to tweak American programmers, some of whom, he says, aren't willing to learn new things when the job market requires it or do the "shit work" that an Indian will undertake. There is something in this slender book that will infuriate everyone, but there are also plenty of moments that will make your eyebrows rise in enlightened surprise. Who knew that it was an Indian-American who came up with the "I Love New York" marketing campaign?

Probably the greatest drawback to the book is that large portions of it appear to have been written as a response to anonymous Internet postings slagging Indian programmers. This gives them more credit than is due. People will say anything online. While one can imagine how painful it is for Sivakumar to read the postings of people recommending that China and India be "nuked" or moaning about how dreadful it is to be forced to take a lunch meeting with one's Indian superior at an Indian restaurant, it still probably isn't worth the time to try to counter that kind of bigotry and bitterness with rational analysis, or even lighthearted foolishness.

On the other hand, anyone who has watched "Lou Dobbs Moneyline" reports on outsourcing knows that the anger about the impact of globalization on American jobs is a potent political issue (though less so, it seems, after the end of the presidential campaign and the relative stabilization of the high-tech job market). So a voice from the Indian side of the equation is well worth hearing.

Sivakumar divides his book between tales of the lives of immigrant programmers and an analysis of the economic benefits of hiring those programmers and engaging in outsourcing. He takes pains to note that hiring immigrant programmers is not the same as outsourcing, a point that some labor analysts might dispute.

When he gets personal, he is especially engaging -- his stories about the impact of Sept. 11 on the community of Indian programmers in New Jersey and New York, where he was then living and working, are compelling and distressing. Indians -- mostly computer professionals working in the World Trade Center, made up the third-worst-hit nationality in the terrorist attacks. But in a particularly lethal double-whammy, after the attacks they had to bear the brunt of racial hatred aimed at them by people equating any dark-skinned foreigner with an Arab terrorist.

Sivakumar is a little less convincing when he defends outsourcing -- here he engages in pretty much boilerplate free-market ideology. Microsoft and Oracle are the kind of companies that make America great. How do they do it? By outperforming their competition, and that means hiring the best talent, wherever one can find it. If they aren't allowed to compete, argues Sivakumar, American companies would not dominate the global software industry.

But Sivakumar is careful to distinguish between the practice of outsourcing and the immigrant Indian programmer experience. Sivakumar is not working in Bangalore for peanuts. His first job in the United States was a $55,000 position. In the late '90s, there was a shortage of talent, and people like him were in demand.

The hatred and anger that got dumped on him for coming to the United States to work is the most distressing part of his tale. For, like many other immigrants, Sivakumar believes in the American dream a lot more fervently than most people born in the U.S. It's a cliché that can't be pointed out too often -- immigrants made this country what it is. Immigrant Americans are as real Americans as you can get.

Maybe the most interesting question raised by Sivakumar's American patriotism is one that he doesn't address at all. If the spread of outsourcing reduces the opportunities for immigrants to come and work in the United States, what does that mean for the future of the American dream?

Shares