The pace of work has been relentless. I don't know if it's because I'm inspired or because I was starved for inspiration for so long. But I've been tapping off a power cell that seems to get charged only in fantastically edgy environments. Many times my partner here, photographer Dwayne Newton, has asked if I'm happy. It's tough to be happy amid such sadness but there are moments. "I'm happy when I'm writing," I reply. And it's true. To paraphrase Hemingway: If some places seem good, it's because we're good when we're in them.

Today, Dwayne and I pile into our muddy four-wheeler and stop at the Mercy Corps office to pick up the ever-patient Mr. Tangal, a local employee who will serve as our translator and liaison during our journey to Muthur. Muthur lies only 10 miles south, across Kodiyar Bay and along the coast, but we will have to detour far inland to reach the place. The camp itself is in a nearby village called Samboor.

The trip is significant, for this will be our first sojourn to a camp located in territory controlled by LTTE (the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam) or, as they're more infamously known, the Tamil Tigers. Since the early 1980s, the militant Tigers have been fighting, violently and futilely, to divide Sri Lanka into two nations: Sinhalese and Tamil.

We're making the three-hour trip for two reasons. The first is that I want to see if the rumors are true that the Tamil camps are being shortchanged in tsunami aid and neglected by the Sri Lanka government. The second is that Anna Young, one of Mercy Corp's expat dynamos, has asked us to see how the off-the-beaten-track camps are faring, compared to the ones we've seen around Batticaloa and Trincomalee.

It's another hat for me to wear. Three weeks in-country, Mercy Corps is still short-staffed and my role has expanded. At some point, my input on these scattered settlements won't be necessary. But for now, Anna says, any intelligence that we can bring back, along with our photographs and stories, will be useful.

As we're driving on the various roads, paved and otherwise, that will bring us to Muthur, Dwayne makes two observations. "You know what you never see here?" he remarks. "Sunglasses." It's true; in most Asian countries, cheap sunglasses are a sidewalk vendor industry. "And the other thing? No bugs on the windshield."

Goddamn, he's right. We've driven more than 600 miles and I haven't seen a single splattered insect. It's the sort of information that we can take no further; our interest in the subject ends with its articulation. But after a while, one begins to feel that every observation is somehow a key, no matter how small, toward unlocking the secret of this strange, polyglot land. It's as if the merest thing, like the way men hold babies, or the fact that elephants appear along the roadsides at 4 in the afternoon, will suddenly provide a cultural "Theory of Everything."

The road gets worse by degrees. As we approach Muthur, we're bouncing through rim-deep ruts filled with mud-red water. We stop at an army check post. Our driver, Sandy (a nickname he earned by miring us in Batticaloa beach), leaves the vehicle and approaches the soldiers. In a moment they smile and wave to us. A guardrail lifts and we amble through.

"Now we are in 'no man's land,'" laughs Mr. Tangal. "Passing from the government to the LTTE areas is like going to another country. Soon we will see the other border."

The dirt track crosses between these warring factions, which have been balanced, since 2002, in a fragile ditente. The road is full of pedestrians, walking back and forth from cosmopolitan Muthur to the Tiger-controlled areas. The women walk and wear saris; the men ride bikes. "These are all Tamils," says Tangal. "Even Muslims are not going into the LTTE zones."

No man's land ends at another checkpoint, where a young Tamil soldier converses with Mr. Tangal and peers at our driver. It's just as well the recruit can't read English; there's a "Singhalese Sports Club" decal on our windshield. But like all the soldiers we've seen, he's as friendly as a Bel Air waiter. The dirty Mercy Corps bumper sticker on our hood seems proof of our good intentions and we're granted entry.

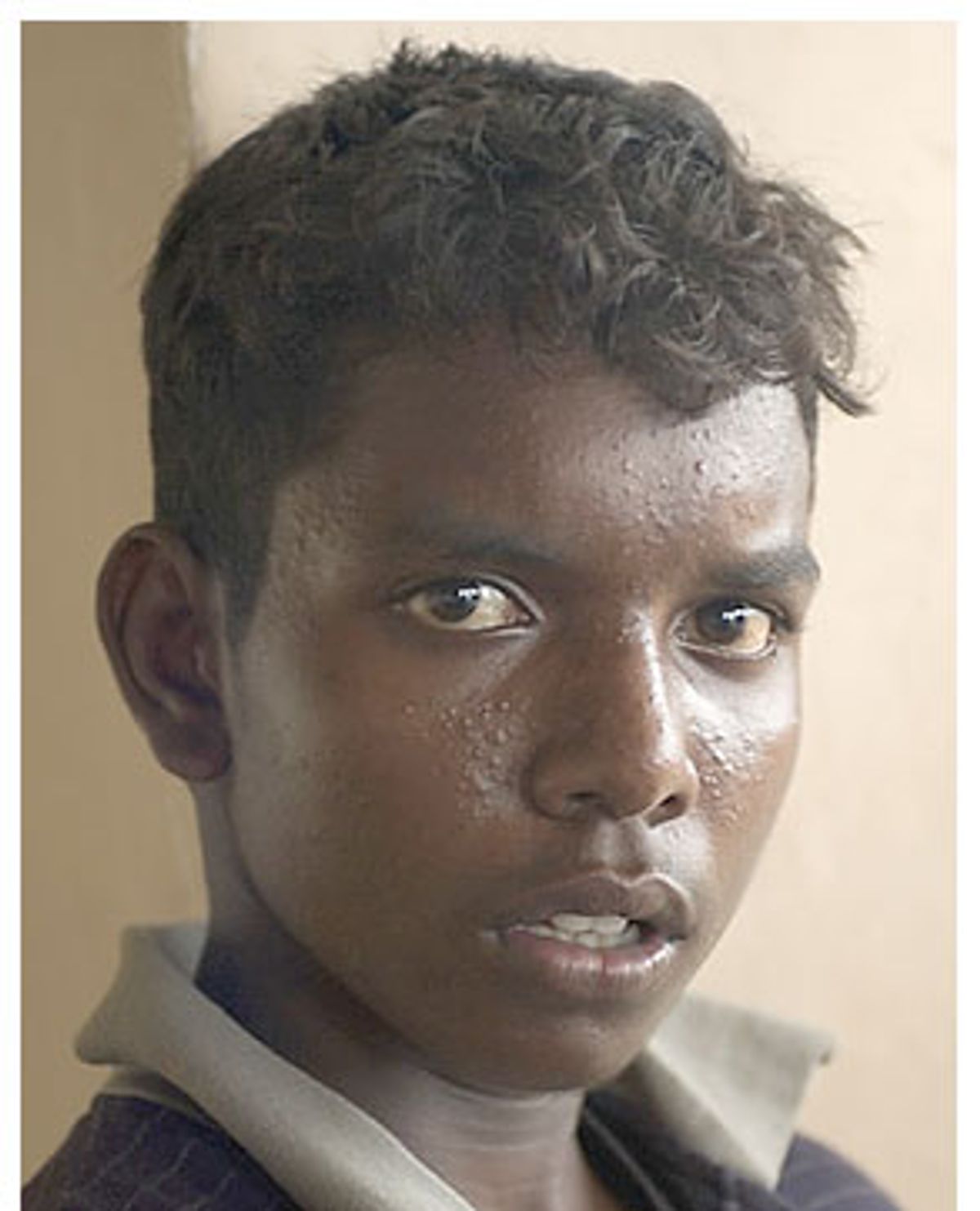

Samboor has been under the control of the LTTE for about 12 years. Entering the area, the tip of an iceberg of Tiger-controlled villages, is like stepping back in time. We see no other vehicles. Brightly painted memorials to fallen Tiger combatants appear along the road, displaying mounted photos of the young Tamil men who perished in campaigns against the Sri Lanka army. It's strange to navigate this backward, sequestered zone, which seems less a homeland than a very rural ghetto. Oxcarts churn the mud as we veer aside to let them by. The local post office is a lonesome edifice, worn as a Wild West antique.

Samboor has been under the control of the LTTE for about 12 years. Entering the area, the tip of an iceberg of Tiger-controlled villages, is like stepping back in time. We see no other vehicles. Brightly painted memorials to fallen Tiger combatants appear along the road, displaying mounted photos of the young Tamil men who perished in campaigns against the Sri Lanka army. It's strange to navigate this backward, sequestered zone, which seems less a homeland than a very rural ghetto. Oxcarts churn the mud as we veer aside to let them by. The local post office is a lonesome edifice, worn as a Wild West antique.

In order to enter the camp, we must have permission from the local LTTE headquarters. We arrive all smiles and shoeshines, parking beneath a bright red flag emblazoned with a roaring tiger, framed by crossed rifles. A meeting of some sort is ending; a dozen Tiger leaders emerge from the tidy white house, slipping back into their flip-flops.

Inside the sparse office, a wooden desk (with a miniature LTTE flag, which I quietly covet) rests beneath a large photograph of Tiger leader Velupillai Prabhakaran in full combat fatigues. There are two men in the room: a short, pudgy man wearing a Timberland T-shirt, and a friendly, gazelle-like youth who speaks no more than a few words of English.

Anyone who has traveled in the developing world, especially in the slowly developing world, is familiar with the bureaucratic gymnastics that attend even the most simple and direct request. Suffice it to say that, as the officer in charge is not in, and as nobody knows where to find him, approval for our visit to the camp cannot be granted.

In situations like this, I usually cleave to the journalist's credo: "It's easier to get forgiveness than permission." In this case, though, the anxious Mr. Tangal is wringing his hands. I see his point. We're not journalists; we're representatives of Mercy Corps. And Mercy Corps might prefer it if we didn't leave Samboor at high speed, a cadre of enraged Tigers on our tails.

It seems hopeless; my attempts to underscore our harmlessness and benevolence are met with long silences and muttered apologies. Finally, for lack of any other way to satisfy us, the Tigers serve us tea.

And it is very good (this is, after all, Ceylon). As we set down our cups and prepare to depart in defeat, another vehicle pulls up, this one from ZOA, the Dutch relief agency charged with managing the camps. Serendipitously, the woman in charge is a former colleague of Mr. Tangal's and has worked with him on myriad local relief projects.

Within moments of leaving the LTTE office we are following the ZOA 4Runner through Samboor, toward the largest of the TRO (Tamil Relief Organization) refugee centers.

It's been difficult to learn the truth about the Tamils in the LTTE-controlled camps. Statements issued by the Tigers' side have claimed interference by the Sri Lanka government and say that food and nonfood supplies earmarked for Tamil refugees are being diverted. It's part of a long campaign to paint the Tamils as victims of oppression and as second-class citizens in this predominantly Buddhist nation.

It's been difficult to learn the truth about the Tamils in the LTTE-controlled camps. Statements issued by the Tigers' side have claimed interference by the Sri Lanka government and say that food and nonfood supplies earmarked for Tamil refugees are being diverted. It's part of a long campaign to paint the Tamils as victims of oppression and as second-class citizens in this predominantly Buddhist nation.

Which, to an extent, they have been. But the fact is that, traditionally, the Sinhalese have long regarded themselves as the "chosen people" of Buddhism and have seen their homeland -- call it Serendib, Ceylon or Sri Lanka -- as the single place where Buddhism is fated to remain unsullied.

Tamils arrived here long ago, too, across what was once a land bridge linking Sri Lanka and India. More were brought over from India to work as low-cost labor on the British tea plantations in the central hills. The Sinhalese were unwilling to kowtow to the British and stuck mainly to the coasts. What emerged, to sketch with broad strokes, was a situation where the Tamils received British educations and went on to become teachers, doctors and other professionals, while the Sinhalese continued to hold the helm of government. We all know where that dynamic leads. There has been, most locals will admit, a strong bias in favor of Sinhalese regarding high-level jobs, places at university, and opportunities for advancement.

But the civil war for an independent Eelam, or Tamil homeland, has been a misguided struggle with no real progress. More than 30,000 people have been lost and the civil war has kept Sri Lanka in the doldrums while its South Asian neighbors thrive. Meanwhile, the ruthless capers of the Tamil Tigers have made the word "Tamil," in some minds, synonymous with fanaticism.

We reach the camp in five minutes. It is located on the edge of Samboor, in what was previously a government agricultural building. There are dozens of tents, set too close together. This is the largest of the camps, with 126 families. It's the only one we'll visit; the next is a two- to three-hour drive on roads that will loosen your teeth. But this camp, we're told, is typical. The people here have been twice displaced: first by the civil war, which forced a relocation, and now by the tsunami.

Nor can they stay here. ZOA has found another location, and is arranging for new homes, also temporary, to be built. Thayalan, the no-nonsense project coordinator for ZOA, agrees to speak with me. I lead with my toughest question: Do the people at this camp feel they're being treated fairly? He puts the question to the refugees standing around us. Yes, they respond; the camp is treated well. There are ample supplies and the refugees are not being shortchanged.

"But what about the rumors that their supplies are being diverted, or denied?" I ask. Untrue, the Tamils respond, shaking their heads.

"ZOA is distributing food and nonfood items," Thayalan elaborates. "And no restrictions have been placed on us. The LTTE is providing medical care. UNICEF has promised books and pens for the school-age children, but they have not yet been delivered." I nod; it's a complaint I've heard in other camps. "And outside caregivers are getting in as well," Thayalan says. At that point, as if on cue, a huge flatbed truck carrying a load of children's clothes and school uniforms backs in through the narrow gate.

"ZOA is distributing food and nonfood items," Thayalan elaborates. "And no restrictions have been placed on us. The LTTE is providing medical care. UNICEF has promised books and pens for the school-age children, but they have not yet been delivered." I nod; it's a complaint I've heard in other camps. "And outside caregivers are getting in as well," Thayalan says. At that point, as if on cue, a huge flatbed truck carrying a load of children's clothes and school uniforms backs in through the narrow gate.

There are a few bottlenecks, Thayalan admits, as two Sri Lanka-based NGOs don't seem capable of living up to their promises. I note this down for my report to Anna; capacity building is one of Mercy Corps' specialties.

As recently as last week, I was receiving concerned letters from friends in the U.S., who were outraged by reports that the Tamils were victims of aid discrimination. Mind you, there are hundreds of camps, and some on both sides of the no man's land are being shortchanged. But this seems to be more an issue of disorganization, or location, than of intentional slight. This observation is confirmed by Roy Wadia, a communications officer for the World Health Organization, as he returns from several Tiger-controlled camps near Jaffna.

"We found them well supplied and very well organized," Wadia tells me. "And we heard nothing from the Tamils that would indicate otherwise."

The fact is, it's difficult to be a refugee in any context. Wearing that label means that you are denied some very fundamental things. There is no doubt that some camps are on the radar of more NGOs and so better off than others. Others are simply more accessible, literally alongside roads, where the most off-the-cuff relief teams might stop to drop off a load of coloring books or Pampers.

From my limited research, I'm reasonably confident that the Tamil camps, in Tiger-controlled areas, are being treated as well as their Muslim, Hindu and Christian compatriots, and that the rumors of their neglect have been greatly exaggerated. Like the refugees I have visited throughout Sri Lanka, the Tamils are a people whose plight transcends religion or ideology.

Shares