The elections held on Jan. 30 in Iraq were deeply flawed as a democratic process, but they represent a political earthquake in Iraq and in the Middle East. The old Shiite seminary city of Najaf, south of Baghdad, appears poised to emerge as Iraq's second capital. For the first time in the Arab Middle East, a Shiite majority has come to power. A Shiite-dominated Parliament in Iraq challenges the implicit Sunni biases of Arab nationalism as it was formulated in Cairo and Algiers. And it will force Iraqis to deal straightforwardly with the multicultural character of their national society, something the pan-Arab Baath Party either papered over or actively attempted to erase. The road ahead is extremely dangerous: Overreaching or miscalculation by any of the involved parties could lead to a crisis, even to civil war. And America's role in the new Iraq is uncertain.

Despite the loftiness of the political rhetoric and the courage and idealism of ordinary voters, the process was so marred by irregularities as sometimes to border on the absurd. The party lists were announced, but the actual candidates running on these lists had to remain anonymous because of security concerns. Known candidates received death threats and some assassination attempts were reported. So the voters selected lists by vague criteria such as their top leaders, who were known to the public, or general political orientation.

Late in the election season, several politicians discovered that they had been listed without their permission and angrily demanded that the lists withdraw their names. So not only were the candidates mostly anonymous, but some persons were running without knowing it. These irregularities made the process less like an election (where there is lively campaigning by known candidates and issues can be debated in public) and more like a referendum among shadowy party lists.

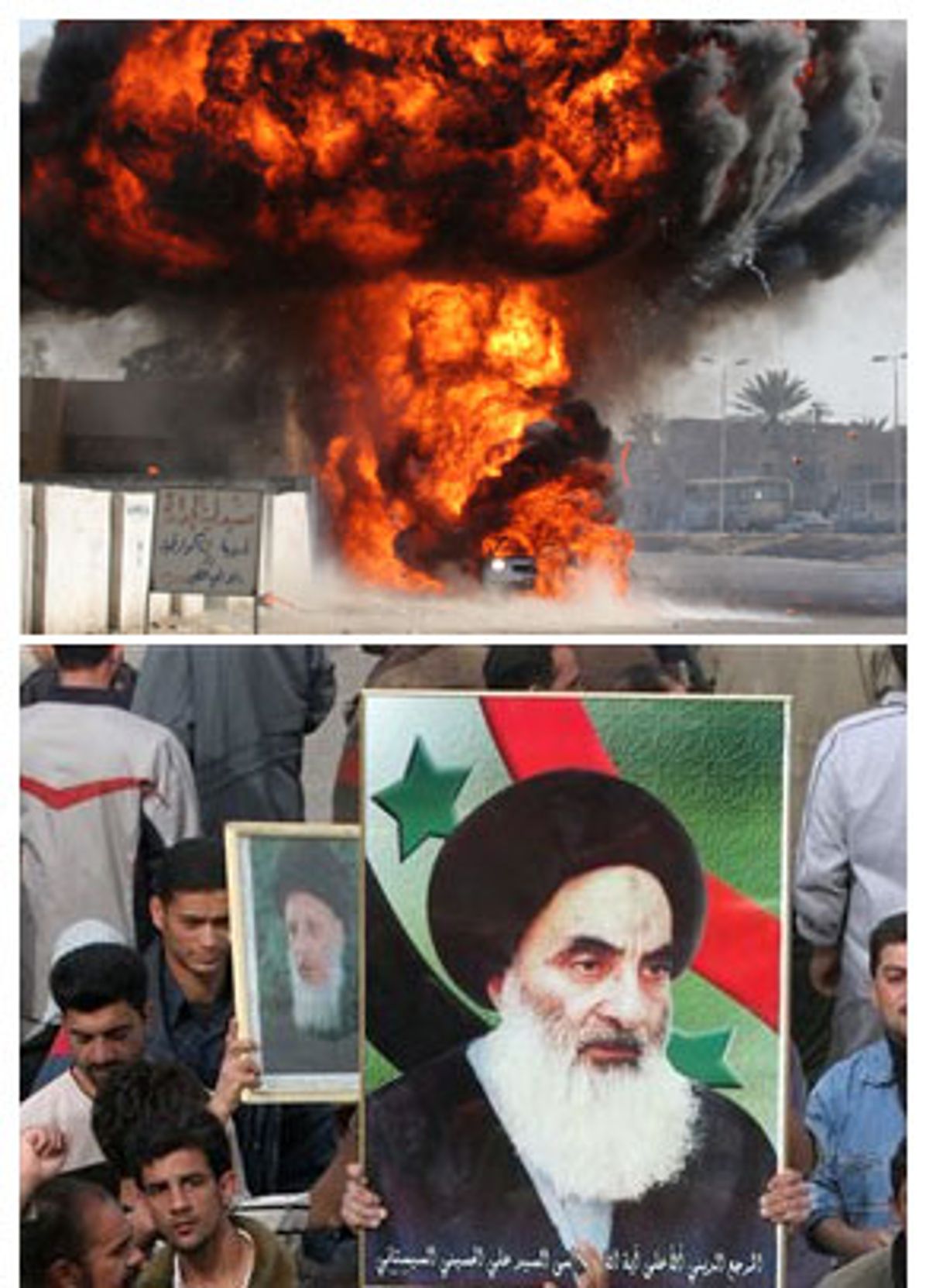

Nevertheless, enough was known about the major party and coalition lists to allow most Iraqis to make a decision. The United Iraqi Alliance was one of six major coalitions, grouping the most important of the Shiite religious parties. Shiites, although they constitute a majority of Iraqis, had never before had the prospect of real political power. Formed under the auspices of the Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, who appointed a six-man negotiating committee in an attempt to unite the Shiite vote, the UIA used the ayatollah's image relentlessly in its campaign advertising. Religious Shiites got the word to vote for "No. 169," the number given the UIA on the ballot, and were carefully informed that it was represented by the symbol for a candle. Its constituent parties, such as the Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI) and the Dawa Party, had in the past struggled to create an Islamic republic under Saddam's harsh repression. Most of them were more used to the technique of the clandestine cell and the paramilitary strike than to the hurly-burly of public campaigning.

Interim Prime Minister Ayad Allawi, an old asset of the American Central Intelligence Agency, led a list of ex-Baathists and secularists, both Shiite and Sunni. For those Iraqis who yearned for a strongman and valued law and order, Allawi's list had a certain appeal. In the north, the Kurdish parties formed a coalition that would attract virtually all of the Kurdish votes (they form about 15 percent of the Iraqi population). The Sunni Arab interim president, Ghazi al-Yawir, also formed a list, the "Iraqis," which had a decidedly secular cast.

The turnout for the elections was higher than had been predicted by the Iraqi Electoral Commission, which had suggested that about half of the eligible voters, or 6 to 7 million, would come out. By the Monday after the Jan. 30 elections, the commission was estimating that about 8 million, or 57 percent of the eligible voters, had cast ballots. This estimate was not founded on any exact statistics, which had to await the counting of the ballots, but appears to have been little more than a guess. The commission's earliest guess was 72 percent, a clear error. In any case, it seems clear that Kurds and Shiites came out in great numbers, and both will do well in Parliament.

As expected, voting was extremely light in the Sunni Arab areas. In Babil province, the trouble spots of Latifiyah and Mahmudiyah avoided violence, but few voters ventured out. The Arabs of Kirkuk, angry about a ruling allowing Kurds who used to reside in the city to vote in local elections, for the most part boycotted the process. In Mosul, the Arab quarters in the west saw firefights, though Kurds and Turkmens came out to vote in the eastern parts of the city. The four polling stations in Baghdad's Sunni Adhamiyah district did not even bother to open. Polling stations in Fallujah, Ramadi, Tikrit and Beiji were reported to be largely empty all day. In the sizable city of Ramadi, only 300 ballots were cast.

The Sunni Arabs of Samarra, a city of some 200,000, cast only 1,400 ballots. The U.S. military had conducted operations in Samarra in October as a prelude for its November campaign against Fallujah, insisting that these military actions would prepare the way for successful elections in these cities. Most of Fallujah was in refugee camps by the time of the elections, and a sullen and angry Sunni Arab population largely rejected the polls as illegitimate because they were conducted under foreign military occupation. The threats brandished by the remnants of the Baath military, which is waging a guerrilla war against the United States and the new order, also took their toll.

The guerrilla war being waged by some Sunni Arabs will not end with the elections. Their leadership is committed to destabilizing the country, pushing the Americans back out, and mounting yet another coup. The resistance consists largely of ex-Baath military along with some religious radicals (very few of whom are foreigners). They have enough munitions, money and know-how to fight for years, though in the end they will lose. The Sunni Arab populace continues largely to support the guerrillas. Over half in a recent poll said that attacks on the U.S. military in Iraq are legitimate.

One disturbing trend in this election was the reinforcement of ethnic political identity. Iraq is a diverse society, but has most often sought forms of politics that deemphasize ethnicity. The price of such an approach, however, has often been authoritarian rule, as under the pan-Arab Baath Party that ruled from 1968 to 2003. In the north of Iraq, Kurds predominate. They do not speak Arabic as their mother tongue but rather an Indo-European language related to Persian (and distantly to English). Their Islam is mystical, traditional and somewhat rural, and most of them are not very interested in the minutiae of religious law. In recent years they have urbanized, as at Kirkuk and Sulaymaniyah, but have developed a relatively liberal approach to Islam and politics. Kurds had long had separatist tendencies and faced severe repression from Baghdad. Under the American no-fly zone of the 1990s, they developed a Kurdistan Regional Assembly, virtually a semiautonomous government, and now fear being reintegrated into Arab Iraq as second-class citizens.

The center-north of Iraq is dominated by Sunni Arabs. Arabs are simply populations that speak Arabic as their native language; they are not a racial category. Sunnis constitute some 90 percent of the Muslims in the world, but are a minority of 20 percent in Iraq. They honor four early "rightly guided" caliphs, or vicars, of the prophet Mohammed and lack a strict clerical hierarchy. Sunni reformists often resemble Protestants in rejecting saint-worship and mediation between God and human beings.

East Baghdad and the south are Shiite Arab territory. Shiites honor the prophet's son-in-law and cousin, Ali, as the rightful successor of Mohammed, and invest the descendants of the prophet with special honor. The Iraqi Shiites do have a clerical hierarchy, at the pinnacle of which is the Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, the chief source of religious authority.

In Iraq, the Sunni Arabs have traditionally predominated, and they have held political power until Jan. 30. During the past three centuries, a conversion movement among tribes in the south has produced a Shiite majority in Iraq. But the Shiites were most often poor, rural and relatively powerless. In the past half-century, many have moved to the cities, gained modern educations, and thrown up religious parties that aim to establish an Islamic republic with a Shiite cast. These parties joined together to form the United Iraqi Alliance.

The UIA appears to have done extremely well in many Iraqi provinces and may well dominate the new Parliament. Because the Sunni Arabs did not come out in force to vote, the Shiite religious vote was magnified. That is, the electoral system is such that parties are seated in Parliament in accordance with their proportion of the national vote. If a party gets 10 percent, it will get about 27 seats. Because of the proportional nature of the election, if one group boycotts, the other groups do even better. The Shiite leadership will try to reach out to the Sunni Arab politicians, including them in the new government and in the constitution-drafting process. But since the Sunnis will have relatively few seats in Parliament, they may be even more sullen than before. Moreover, the politics of the UIA may not be to their liking.

If the United Iraqi Alliance can form a government, probably in coalition with smaller parties, it will almost certainly move in two controversial directions. First, it will seek to implement religious law in the place of civil law for matters of personal status, and possibly in other realms, such as commerce. Islamic law has provisions for matters such as marriage, divorce, inheritance, alimony and so forth. Muslim fundamentalists throughout the world have adopted as one of their main political goals the repeal of civil laws that were most often adopted during or just after the age of European colonialism (roughly from the mid-1700s until the 1960s), and to replace them with a rigid and often medieval interpretation of Islamic law.

This form of Islamic law (which in other hands can be dynamic and innovative) would typically deny divorced women any inheritance, give girls half the inheritance received by their brothers, restrict women's right to initiate divorce, restrict women's appearance in public, and make the testimony of women in court worth half that of a man. Middle-class Sunni Arabs and educated women, along with most Kurds, would likely strongly resist this initiative. The Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq, among the main Shiite parties, and Grand Ayatollah Sistani have already telegraphed their desire for this change.

The other big political fight likely to ensue in the new, Shiite-dominated Parliament is over a centralized government versus a loose federation. The Kurds want what they call a "Canada" model, or perhaps one modeled on the Swiss cantons, in which the central government cedes many rights to the provinces. In American terms, the Kurds want "states' rights." Their maximal demands are the creation of a Kurdish super-province, Kurdistan, on an ethnic basis; the joining to Kurdistan of the oil-rich Kirkuk area; no federal troops on Kurdistan soil; and the retention of petroleum profits inside the Kurdistan province.

In contrast, the Shiite political traditions in Iraq have all favored a strong central government, and Baghdad and Najaf are unlikely to want to give away so much to "Kurdistan." Since the Kurds will be well represented in Parliament, have a big, well-trained paramilitary, and have a veto over any new constitution, this particular struggle is one they will not concede without a fight.

Although the vast majority of Iraqis want U.S. troops out of their country immediately or soon after Parliament is seated, according to a recent Zogby poll, it seems unlikely that the new political class will call for a precipitate U.S. withdrawal. They are still afraid of being assassinated by the guerrillas. Over time a split may develop between the rank and file, impatient for an American departure, and politicians who still depend on U.S. forces for their own protection. When Iraqi leaders feel strong enough to deal with the guerrillas by themselves, they will have a strong impetus to ask the United States to leave altogether. All Iraqis remember Abu Ghraib and other missteps of the U.S. military in their country.

The new Iraq is forming, but its formation will involve struggle as well as compromise, strong stands as well as bargaining. How successful post-Saddam Iraq is depends very much on whether all groups are mature enough to make the necessary compromises and strike a balance between the religious and secular, and between the center and the provinces.

Shares