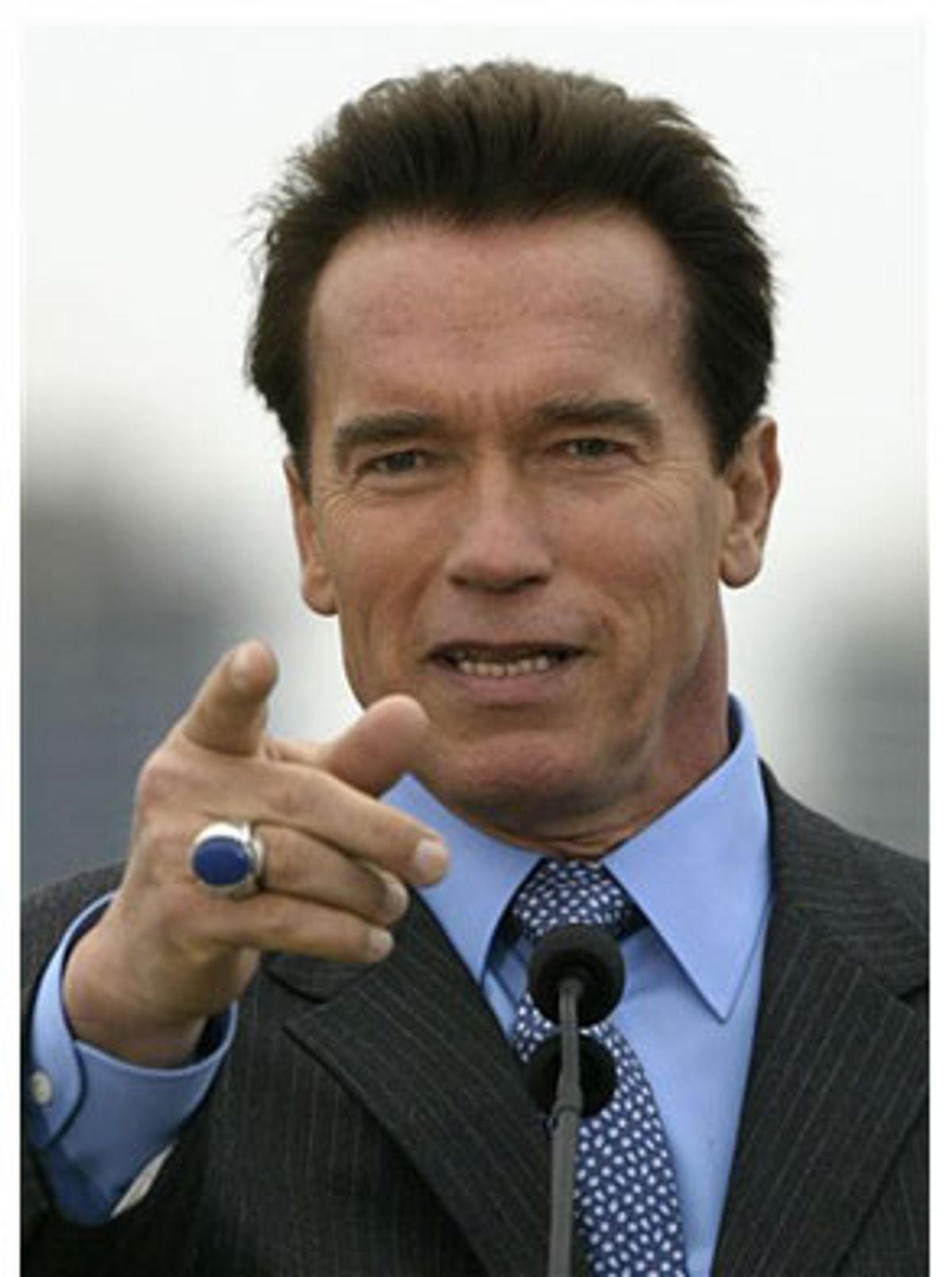

Titillated by the star power of his populist coup in California, the national media has swooned in Arnold Schwarzenegger's muscular embrace for over a year. The New Yorker profiled him as "Supermoderate!" Wired found him to be "surprisingly effective." The editors of the New York Times proclaimed, "The last action hero can seemingly do no wrong." On the cover of its January 2005 issue, Vanity Fair featured the leather-jacketed Schwarzenegger posing atop a Harley with his silken spouse, Maria Shriver. The story, like so many others, portrayed the glam couple as the future of American politics: bipartisan, moderate, effective ... presidential.

At first, the new governor sporadically fit the role of social liberal but fiscal conservative. He endorsed stem cell research, strengthened protections for domestic partners and supported access to public records. Conversely, he campaigned against reforming the penal law, called for setting up a DNA database for felons, and vetoed a bill allowing illegal immigrants to get driver's licenses. But, overall, people bought into his seeming moderation -- fully two-thirds of the state's general public favored his governorship. No California governor in modern times has enjoyed such a broad-based mandate to tinker with the government of the world's fifth-largest economy.

But with his defiantly immoderate State of the State speech in early January, when he proposed to drastically cut back education and social services in lieu of taxing the rich, Schwarzenegger blindsided liberal Californians with his nakedly Republican agenda. This week, the celebrity governor travels to Washington to mine his relationship with President Bush and the GOP-controlled Congress to boost federal spending for California. Since arriving in Sacramento, Schwarzenegger has:

For more than a year, proximity to the "Governator" has blinded Democratic Party leaders, reporters, editors and the public to the tawdry reality taking place in front of their eyes -- the huckstering of a conservative product line and the glorification of the Schwarzenegger brand in California's highest public office.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

The world was stunned and amused, and perhaps hopeful, on Oct. 7, 2003, when a huge plurality of voters believed Schwarzenegger would kick the "special interests" out of Sacramento. But since taking office, the new governor has collected $26 million -- in chunks ranging from $21,200 to $1,000,000 -- from individuals and companies involved in high finance, real estate, insurance, construction, energy sales, entertainment, pharmaceuticals, electronics, prison corporations and major news media. (In his first year in office, Gray Davis collected $13 million in special-interest contributions.) In addition, five nonprofit corporations set up to pay for such items as the governor's luxury hotel suite in Sacramento, and his trips abroad, are not required to disclose their sources of money.

His public donor list, however, is studded with the names of Republican businessmen, such as Fox News tycoon Rupert Murdoch and mega-developer (and San Diego Chargers owner) Alex Spanos. But it also includes big-time Democratic Party fundraisers, such as grocery store magnate Ron Burkle and financier Eli Broad. And then there is David Booth. Who is Booth? He is the chairman of Dimensional Fund Advisors, a $65 billion private equity firm in which Schwarzenegger has disclosed an investment greater than $1 million.

The governor makes a big deal about not taking campaign contributions from organized labor and public employee unions, which he labels "special interests." But his 2003 statement of economic interests reveals that he did not object to accepting more than $100,000 in dividends from Dimensional, which manages retirement funds for those very same special interests, including CalPERS, California's public employee pension fund.

Dimensional also handles labor union pension funds, such as the Empire State Carpenters, Pennsylvania Teamsters, United Mine Workers of America, and teacher pension funds in Missouri and Michigan. Playing both sides of the capitalist equation, Dimensional holds stakes in numerous corporations that do business in California, such as Merck, Pepsi, Raytheon, Sprint, Verizon, WellPoint, AT&T, and the Tribune Company (owner of the Los Angeles Times).

On a regular basis, the multimillionaire governor makes important executive decisions that could affect the health of his personal wealth reported to be as much as $100 million. At the same time, the California Political Reform Act forbids him to "participate in making or in any way use his official position to influence a governmental decision in which he knows or has reason to know he has a financial interest." When he has a conflict, he must recuse himself from action. So far, Schwarzenegger has not recused himself from signing or vetoing any legislation that could directly or indirectly benefit his personal finances.

"We have never had a governor with this many investments," says Robert Stern, president of the nonpartisan Center for Governmental Studies in Los Angeles. "Until these assets are sold off, the potential for a conflict still exists." Stern adds that state law requires the official to recuse himself for a full year after the asset been sold. He is also not supposed to act on matters that significantly affect a source of income from the previous year.

To shield a wealthy government official from being paralyzed by possible conflicts of interest, the Political Reform Act allows the officeholder to place assets in a blind trust managed by a "disinterested party." The theory is that, after a time, he will no longer know what he owns. The trustee (who cannot be a relative) is supposed to have little or no contact with the official. He is empowered to liquidate the original portfolio and to buy new assets, which are unknown to the official. In apparent violation of the reform act, Schwarzenegger designated as his trustee his close friend and financial advisor, Paul D. Wachter.

"We've been friends for 25 years and been in business together for less than 15 years," Wachter tells Salon about his relationship with Schwarzenegger. "I am his main person in the whole business, financial, legal area. And, obviously, a close confidant. As the blind trustee, I manage all his money."

It doesn't take a doctorate in ethics to see that Wachter is exactly the wrong person to serve as the disinterested trustee. "'Disinterested party' excludes family and business associates," says Tracy Westen, Stern's colleague at the Center for Governmental Studies. "The word 'blind' means that the trust is not being run by someone with whom you interact on an intimate or a daily basis. If the beneficiary of a blind trust were to get some sense of how the trust is being invested through a casual remark, or a deliberate remark, that might affect a governmental decision. If a longtime business partner is handling the trust, I would certainly question whether it was truly blind."

Last March, Schwarzenegger appointed his friend, Wachter, to a state jobs commission. In May 2004, Schwarzenegger took his personal financial advisor, Wachter, on a trip to Israel, Jordan and Iraq to look for business opportunities. In July, Schwarzenegger appointed his blind trustee, Wachter, to the Board of Regents of the University of California, which controls billions in state money.

Furthermore, Wachter is anything but disinterested in the link between the governor's political and financial success. Wachter's company, Main Street Advisors, has long managed much of the Schwarzenegger fortune. The economic disclosure statement that Wachter filed when he became a regent shows that he and Schwarzenegger are linked by millions of dollars' worth of partnership investments. Wachter, for example, also has more than a million dollars invested in Dimensional Fund Advisors.

The Schwarzenegger-Shriver economic disclosure statement filed in December 2003 reveals that the couple sold millions of dollars' worth of corporate stocks when the governor assumed office and set up a blind trust. Yet at the time Schwarzenegger's blind trust was created, he and Wachter were jointly invested in 10 partnerships, including Acacia Partners (which deals in public stocks), Angel Investors (a venture capital firm), Apollo Investment Fund (specializing in leveraged buyouts) and Pinpoint Investors (a stockholder in Cell Guide Ltd., which develops cellphone technology).

As his friend, confidant and financial advisor, Wachter is likely to share conversations with the governor that grant him inside knowledge of Schwarzenegger's plans and priorities. And Wachter certainly has every financial incentive to influence taxation policies and the government regulation of any number of industries, including, say, cellphones, in ways to benefit himself and his client. Wachter says that while he shares these investment "vehicles" with Schwarzenegger, he qualifies as a disinterested party. Why? His lawyers OK'd him as the blind trustee.

"We are not trying to create a blind trust which says the governor and I never met," Wachter says. "Or that I sold all his assets and he does not know anything in his portfolio. Instead, as of the date of his inauguration, he has no involvement with anything in the portfolio." When a new disclosure statement is released in March, says Wachter, it will show which of the original assets placed in the blind trust have been sold and which have been retained. "You don't have to liquidate everything," Wachter carefully points out. "The key point of a blind trust is that the governor is supposed to be kept away from real and apparent conflicts of interest. You do not want people even to feel like there might be a conflict of interest."

Despite Wachter's words, his close relationship with Schwarzenegger certainly presents at least the appearance of a conflict of interest.

See how you feel about conflict of interest when you visit the governor's business Web site, Schwarzenegger.com, where you can vote on whether he will go down in history as bodybuilder, movie star or governor. You might enjoy bidding for an autographed baseball hat on the "Arnold Auction" page or clicking on the link to an official press release about the governor's November trip to Japan. The site's brazen trading on Schwarzenegger's governorship is just one example of the synergy between his official duties and his business brand.

Not too surprisingly, the disinterested Wachter is tasked with building and protecting the Schwarzenegger brand, which is undergoing a makeover, according to an article in the Los Angeles Times Magazine in October, in which Wachter remarks, "We're still learning what the new brand is and what to do with it and what not to do with it."

In the 1990s, Schwarzenegger enjoyed a huge marketing presence in Japan as a spokesman for Hops beer, Nissan noodles and DirecTV. (Japander.com features these clips, noting that the Schwarzenegger ads are "the most popular on the site, especially now that he is the governor of California.") According to Rob Stutzman, the governor's director of communications, Schwarzenegger has asked Wachter to find a new advertising opportunity for him in Japan. "Since he became governor, there is a greater interest in him. He said he would take the money to open up a trade office on behalf of the state," Stutzman confides.

In November, Schwarzenegger took 57 state officials and businesspeople on a junket to Japan, where again his public and private fortunes converged. The trip was paid for by one of the privately funded nonprofits that the governor uses to subsidize his epicurean lifestyle (no commercial airline flights or per diem meals for him). In Japan, he met with officials of Toyota Corp., which has contributed $258,000 to his campaign committees, promising to "move mountains for them" in California, where the company reportedly wants to build a Prius plant. Then he made a series of campy public appearances pitching California as a business opportunity to audiences that are just wild about buying his DVDs.

There are other intersections between the governor's private and public capital. Schwarzenegger has been receiving income from six private Goldman Sachs partnerships worth more than $2.4 million. According to the firm's Web site, Goldman Sachs has a stake in the California energy market and would benefit from deregulation. The firm owns a power supply contract with the state Department of Water Resources. It also underwrote $3.3 billion in financing for Calpine Corp., another player in the electricity deregulation game.

Last year, Goldman Sachs helped underwrite the economic recovery bonds that Schwarzenegger campaigned for and used to plug last year's and this year's budget holes. Since the governor took office, the investment bank has participated in underwriting the sale of more than $23 billion in state bonds, including general obligation bonds and various pension and energy bonds.

At the same time that Schwarzenegger was pushing energy deregulation and deficit bonds on the state, he had a substantial amount of money invested in Goldman Sachs. Because of his history of partnering with Goldman Sachs, Dimensional and other financial management companies, Schwarzenegger is positioned to benefit, at least indirectly, from the privatization of California's public employee pension funds, which will need financial management services.

"Anytime a government official is in a position where the decisions he makes can financially benefit himself, a close colleague, a business partner or his associates, it is troubling," says Weston. "In this case, one would like to see the governor make decisions based purely on their merits, without any hint of self-dealing or favoritism. Unfortunately, arrangements like this sometimes create that impression."

This is not to say Schwarzenegger is deliberately plotting to enrich himself by creating underwriting business for Goldman Sachs, or by facilitating the firm's desire to deregulate the energy market, or by moving to privatize the $171 billion CalPERS portfolio. But by simply following his instincts, he cannot help but position himself to gain collateral benefits. Goldman Sachs and Dimensional could eliminate the appearance of conflict by cutting their business ties with the state for as long as Schwarzenegger is governor -- but that has not happened.

Government laws regarding conflict of interest were written by state officials to police themselves, so, naturally, they are riddled with loopholes. For a real conflict to occur, the official action must have a "significant financial effect" on the governor, or his family, or upon the source of his income that is affected by his action. The governor's veto last September of a bill that regulated the use of dangerous performance-enhancing dietary supplements (PEDS) by high school athletes appears to have met this criterion: The legislation posed a significant financial threat to a Schwarzenegger-owned corporation.

The bill, authored by state Sen. Jackie Speier (D-San Francisco), discouraged student athletes from using performance substances listed as dangerous by the state, and prohibited the sponsorship of school athletic programs by PEDS manufacturers. Signing it was a no-brainer from a public health point of view, as many of these products are anabolic -- they rip and shred muscle tissue, while exciting the cardiovascular and nervous systems. Popular performance supplements, such as ephedrine and androstenedione, have been linked to the death of young athletes. On the other hand, the bill threatened to destroy a California PEDS market easily valued at more than $10 million.

In 2003, Schwarzenegger earned more than $100,000 from a company he owned and operated, Classic Productions. The firm produces the governor's annual bodybuilding exposition, Arnold Classic, in Ohio. This event is sponsored by a score of PEDS distributors. The governor is also the executive editor of two muscle magazines that are plump with PEDS advertisements. Clearly, he should have recused himself from acting, thereby allowing the bill to become law. Instead, to paraphrase the Political Reform Act, he used his official position to influence a governmental decision in which he knew or had reason to know that he had a financial interest. But that's not how Schwarzenegger spokesman Stutzman sees it. "The veto of Speier's PEDS bill does not rise to the level of a conflict of interest," he says.

Regardless, says Roger Blake of the California Interscholastic Federation, a state-funded organization of high school sports officials, "The use of steroids and PEDS has grown to frightening levels. Just because Schwarzenegger vetoed the bill does not mean the problem will go away."

That Schwarzenegger's self-dealing is not seen as a minus by his team typifies the Reagan-admiring governor's approach to economics (laissez-faire) and accountability (none). (His Council of Economic Advisors includes such Reagan-era "supply-side" economists as Milton Friedman and Arthur Laffer.) Guided by council member James L. Sweeney, who is a vocal proponent of liquidating energy regulation, Schwarzenegger wants to open up California's electricity market to unregulated trading and gaming, despite the glaring failure of electricity deregulation, which has, so far, bankrupted the state's largest utility company and cost consumers tens of billions of dollars. To that end, the governor vetoed a bill in September that would have partially reregulated the electric utilities. Nor has he followed through on his campaign promise to negotiate lower consumer rates.

"When the Chamber of Commerce says 'jump,' Schwarzenegger jumps a mile into the air," says Rico Mastrodonato, Northern California director of the League of Conservation Voters.

Mastrodonato, like many liberals, still dreams that the governor will be more of a moderate than, say, President Bush. "Republicans are abysmal on environmental issues, but he has given us reason to hope he will buck his own party." The league was pleased, for instance, when Schwarzenegger signed bills conserving portions of ocean and forest and getting dirty diesel buses off the road.

But Schwarzenegger's environmental record, which supporters and the national press spotlight as evidence of his moderation, is seriously flawed. The record shows that Schwarzenegger vetoed legislation requiring utilities to generate 20 percent of their energy from renewable sources. He vetoed a bill to make public schools energy-efficient, a bill to reduce energy pollution in the Port of Los Angeles and a bill to limit the use of gas-powered vehicles in wildlife refuges. He put political muscle behind November's victorious Proposition 64, which weakens the public's ability to sue corporate polluters.

Implementing his anti-labor, anti-consumer agendas, Schwarzenegger vetoed a bill penalizing employers for locking workplace safety exits. He vetoed a 50-cent raise in the minimum wage, a bill requiring employers to tell employees that their e-mail is being read and a bill protecting used-car buyers from fraud. According to a UC-Davis study, Schwarzenegger reduced workers' compensation insurance benefits by as much as 70 percent, while failing to significantly lower the price of insurance.

The people's governor has consistently vetoed bills opposed by the hospital and drug and insurance industries. He rejected a reduction in prescription drug prices, a law requiring pharmacies to disclose kickbacks from drug companies, a law protecting uninsured people from excessive hospital charges, a mandate to reduce hospital-acquired infections and an attempt to improve breast cancer screening practices.

Six months into his term, an emboldened Schwarzenegger created a commission to reorganize government bureaucracy. This was nothing new. Since 1968, there have been 29 such commissions. But Schwarzenegger's version, called the California Performance Review, pursues a right-wing agenda and would centralize power in the governor's office. Focusing on ways to abolish government regulation and reduce business taxes, the panel's recommendations included killing property tax relief and renter assistance to low-income seniors and disabled people, and cutting state subsidies to child care providers. The panel advised eliminating regulatory restrictions on oil refining, weakening pesticide laws, and abolishing oversight of mining and dredging in San Francisco Bay. In January, the governor adopted many of the panel's suggestions. If the Legislature does not rubber-stamp his reorganization plan, the governor threatens to put it, and a series of constitutional amendments that disempower the Legislature -- including a redistricting plan that could give California Republicans more sway at the polls -- to a popular vote this year.

At the core of the "reform" plan is the abolition of 88 citizen-run boards that meet in public and operate independently of the governor's will. Many of these boards -- whose members are paid $100 per meeting -- make important regulatory decisions affecting workers' compensation, energy, waste management, water, seismic safety, pest control, library construction, education, guide dogs for the blind and oversight of managed-care corporations. Some of the boards targeted for elimination are responsible for licensing and monitoring technical professions, such as doctors, pharmacists, mortgage brokers, registered nurses, accountants, general contractors, dentists, optometrists, physical therapists, security guards and veterinarians.

Jean Ross, executive director of the nonpartisan California Budget Project in Sacramento, says that the plan calls for transferring the professional staffs of the licensing boards to the Department of Consumer Affairs, where decisions are made in secret and the governor rules by fiat. She says that will not save any money, although it will end public participation in the process.

"It's an enormous power grab to put a super-strong governor's office under the guise of doing the people's work," says Assemblyman Mark Leno (D-San Francisco). "It will increase the budget, and the Department of Consumer Affairs can't handle it."

California nurses are up in arms. Not only is Schwarzenegger refusing to implement a law requiring safe nurse-patient ratios in hospitals, he intends to abolish the Board of Registered Nursing.

"The board has been in existence for a century," says board member Jill Furillo, a registered nurse. "It was set up to take licensing away from the hospital industry and to operate outside its control. We certify schools of nursing, oversee licensing standards and testing, investigate complaints and operate in full view of the public."

When the governor spoke recently at a corporate-funded conference celebrating California women (organized by Shriver), a row of nurses chanted slogans protesting his healthcare policies. "Pay no attention to those voices over there," said the governor, as the nurses were booted out of the hall. "They are the special interests. Special interests don't like me in Sacramento because I kick their butt."

Of course, the reverse is true.

Schwarzenegger designed his initial campaign to replace Gov. Gray Davis on the premise that California's business economy was drowning in government regulations, high taxes and workers' compensation costs. And it worked. Fed up with Davis' constant fundraising and his blatant sale of public policy to the highest bidders, one in five Democrats voted for the Republican movie star, as did 44 percent of Independents.

But the state was not drowning in regulations, observes Elizabeth Hill, the nonpartisan financial analyst for the Legislature. California business profits were up sharply in 2003, Hill reports, due to increased sales, the availability of cheap labor, and hundreds of millions of dollars a year in government subsidies to business, called tax credits. For that matter, Fortune magazine rated California as the best state in America in which to do business in 2002.

No wonder, according to the latest figures available from the Franchise Tax Board: 52 percent of California's profit-making corporations pay only the minimum income tax of $800 each year. That includes 46 corporations that gross more than $1 billion each. Hill notes that personal income taxes in California account for 48 percent of general fund revenues -- up from only 18 percent 40 years ago.

The chief economist at the Legislative Analyst's Office observes that the huge deficit occurred because state revenue from taxation on capital gains income fell from $17 billion to $6 billion in one year after the dot-com bust in 2001. Plus, Schwarzenegger rolled back the car registration fee, digging the hole even deeper.

Despite the strong state economy, next year's $111.7 billion budget has a $9 billion hole. Schwarzenegger proposes to bridge the gap by borrowing $2.2 billion from Wall Street, diverting $3.8 billion from education and transportation programs, and cutting $4 billion from health programs, affordable housing, local governments, welfare services and public employee pension funds.

State officials are horrified.

Legislative analyst Hill says that the budget realistically portrays the size of the deficit problem, but it goes for the quick fix for the second year in a row and fails to find a permanent solution. The governor is prioritizing spending cuts over increasing taxes, she notes, primarily at the expense of mass transit programs, people on family welfare, K-12 schooling and higher education.

The state treasurer, Phil Angelides, says Schwarzenegger's policy of paying for operating costs with "credit cards" has increased the debt load by 40 percent since Gray Davis left office. State Controller Steve Westly says the massive social service cuts "will harm Californians now and threaten our competitiveness long term."

Assemblyman Leno, who sits on the Appropriations and the Revenue and Taxation committees, remarks: "It takes third-grade math to realize Schwarzenegger is not balancing the budget. He tours the state cutting an oversize credit card with a giant scissors at the same time he is borrowing more money than has ever been borrowed. It is less than honest."

Experts at the nonprofit California Budget Project estimate that the deficit could be wiped out by closing business tax loopholes and by reinstating the previously reduced personal income tax on earnings over $1.3 million (which would cost the average millionaire an extra $8,300). Studies show that, measured as a share of income, California's poorest families pay the most in taxes.

Remarkably, the governor intends to seize an $85 million cost-of-living increase in federal Supplemental Security Income money targeted to assist blind and disabled people, and use it to fill in the budget gap. He is also cutting family welfare grants (CalWORKS) by 6.5 percent, and deleting a scheduled cost-of-living increase for that program. Meanwhile, he is "augmenting" judiciary and prison budgets by $600 million.

"It is amazing that the working people in this state are being blamed for the cost of government," Leno continues. "Schwarzenegger is cutting support to homecare workers who take care of our elderly and infirm. He is cutting monthly stipends for young mothers transitioning to work. It is not about saving money. It is mean-spirited."

It is also about competence. Last year, educators agreed to a $2 billion reduction in classroom funds after Schwarzenegger solemnly swore to give the money back this year. He didn't. Schwarzenegger made a deal with Indian casino owners that was supposed to bring in a $1.3 billion jackpot for the state this year. It only netted $16 million. Again, the governor didn't come through.

Leah Shue, a veteran teacher in the Sonoma Valley Unified School District in Northern California, describes a recent faculty meeting where teachers expressed their anger at Schwarzenegger's educational "reforms," which include defunding schools, privatizing teachers' pension funds and, as he said during his State of the State address, a proposal that "a teacher's pay be tied to merit, not tenure."

"A lot of teachers in the room had voted for Schwarzenegger," Shue says. "For some reason, a lot of liberals saw him as approachable. They were shocked and hurt by what he said about teachers. I think they had trusted him and felt betrayed. Now they see that he had a hidden agenda -- a right-wing agenda."

During much of his career, Schwarzenegger posed naked in front of cameras wearing a figurative Buy Me sign. People love his image, and millions buy his brand. But in the Hollywood world in which money, media and mass manipulation are everything, it must be easy to lose track of who you really are, or who you might have been. Schwarzenegger recently told the Los Angeles Times, in all seriousness, "As far as I am concerned, no one can buy me."

Would that it were true.

Shares