Shiite soldiers on the roof, Kurdish fighters down below, and no Sunnis to be seen. That was the picture at one polling station on Election Day in the violence-racked northern Iraqi town of Mosul. Now, in the wake of the publication of the election results, the question is whether that picture will prove to be emblematic of Iraq's future. Judging from the mistrustful, strained and often outright poisonous relations between Kurds and Arabs here, the prospects for harmony could be bleak.

The Hay al-Tahrir neighborhood in Mosul is mostly Sunni Arab, but the troops guarding the Jana'ain high school where the polling took place were pulled in from the Shiite south and the Kurdish north. The election officials who oversaw the polls were all from outside the city -- 11 of them Christians and one Yezidi. In fact, almost everything that had to with the elections in Mosul was imported, and hardly any of it was Sunni Arab.

Iraq's election results have led to much hand-wringing about the non-participation of the formerly dominant Sunni minority. For a stable Iraq, goes the received wisdom, Sunnis have to be included in the political process, particularly in the drawing up of the new constitution. But as always, politics are being dictated and overtaken by realities on the ground. And in Mosul -- as well as the oil-rich city of Kirkuk, which is being claimed by the Kurds -- the reality seems to be that the Sunnis are going to be mercilessly squeezed. It's payback time.

Both Shiites and Kurds harbor dark memories of decades of oppression by Sunni governments in Baghdad. They now eye an opportunity not only to exact revenge but also, as they see it, to roll back some of the inroads that the Sunni Arabs have made into their territories. This goes particularly for the Kurds. The Americans were aware of the dangers of sectarian tensions in Iraq after the invasion; indeed, they saw Mosul as a microcosm of the rest of the country. The American commanders there made early efforts to involve the local population in the running of their city. But locally recruited police and Iraqi National Guard units proved to be unreliable, melting away and allowing the city to be practically overrun by insurgents after U.S. troops chased them out of Fallujah in November. Since then the Iraqi government and the United States have relied mostly on Kurdish fighters from the north and some Shiite units from the south to secure the city.

"The insurgents actually did us a favor," said a senior U.S. commander in the region recently. The U.S. forces had been aware for some time of the "problems" with the locally recruited, mostly Sunni Arab, troops, he said. But because of "political sensitivities" they had been unable to do anything about it. They could not bring in loyal Kurdish fighters, because it would upset the Sunni majority in the city and anger Turkey, which is extremely wary of any expansion of Kurdish influence in Iraq. When the insurgents poured into the city and the security forces disappeared, the officer said, it gave Iraqi and U.S. authorities the excuse they needed to go ahead and send in the Kurds and the Shiites.

If the Jana'ain polling station was any indication of how a Shiite-Kurdish alliance was going to play out in the new Iraq, it offered a disturbing preview. Deeply suspicious of each other, the troops were bound together by two impulses: a realization that they would stand or fall together on a violent Election Day in this fractious city, and a hatred of the Sunni Arab "irhabi," or "terrorists" -- a label they applied to the whole of the population that surrounded them and that it was their mission to protect.

Many of the Shiite troops on the roof appeared to be shockingly young. Yet they belonged to the second division of the Interior Ministry's Special Forces and were referred to by the American soldiers in the area as "the commandos." They said their detachment had guarded Ayad Allawi, Iraq's interim, secular Shiite prime minister, until November. Since then they had been "hunting" terrorists in Mosul, they reported with the boastfulness that comes easily to young, heavily armed and well-supported militiamen.

As the plumes of smoke from explosions around the city crept toward the sky on Election Day, the soldiers on the roof bragged about their prowess. "I killed six terrorists just two weeks ago, in a mosque in the center of town," said Suheil, a young soldier from the Shiite holy city of Najaf. His friend Ahmed chimed in excitedly: "It was something big. We used an RPG to blast the mosque. These terrorists always hide in mosques." When a firefight broke out later in the day near the polling station, they said that their troops had apprehended 21 "terrorists" in a nearby mosque where they had been "planning attacks."

In between recounting war stories, the recruits cadged cigarettes, inquired about the West -- one soldier struck up conversation with a very graphic remark about the Michael Jackson child molestation trial -- and asked to use my satellite phone to call their mothers in Najaf. When it came to the situation in Iraq, they were very clear. Making cutting motions with their fingers across their throats, they said, "Don't go out into the streets here: The terrorists will kill you."

The Kurds, almost to a man, are even more ferocious in their attitude toward the local Sunni Arab population. They refer to Sunnis as murderous "dogs," two-faced liars, animals and other epithets that indicate a deep distrust and even hatred of a group clearly regarded as an enemy. They trot out a litany of complaints, mainly but not exclusively dating from the time of Saddam Hussein, when they say they were attacked, gassed and ethnically cleansed from their lands by Sunni Arabs.

Armies policing civilian populations rarely have a light touch, and the Middle East is not known for its enlightened policing methods to begin with. So it was unsurprising, but still disturbing, that in the space of just a few days, I observed Kurdish fighters in Mosul arresting and severely beating several suspects, at least one of whom was clearly no terrorist. In one case, the beating took place right after an ambush in which two soldiers were killed and tempers were frayed, but on another occasion it was obvious that the man in custody, though he had perhaps pilfered a few things from a disused army base, was certainly not an "irhabi."

The 104th Battalion of the 23rd Brigade of the Iraqi National Guard, which is to be integrated into the new "Iraqi Forces" made up of both ING and army units, is based at the Al-Kindi military base, a former chemical factory compound in Mosul. The battalion is made up entirely of Kurdish peshmerga fighters who for years battled Iraqi government troops from their mountainous redoubt in the north. After the Gulf War of 1991 and the imposition of the no-fly zones, the Kurds maintained an autonomous semi-state in the north, with U.S. help and international aid. After the Americans and their allies toppled Saddam in 2003, the Kurds rejoined the Iraqi political entity -- to a degree. They brook no interference in their internal affairs from the central government, but they do participate in the country's central political institutions and are considered the Americans' staunchest allies there.

Of the approximately 140,000 peshmerga, a little less than a third are integrated into the new Iraqi armed forces. But the integration is only in name. The units have a double structure: peshmerga and Iraqi. One colonel at the "Fermandiya," the sprawling peshmerga headquarters in Dohuk, dismissively said of one officer, "He's only a general in the Iraqi structure. In the peshmerga, I outrank him."

The peshmerga commander for the "frontier" that stretches from Mosul to Kirkuk is Gen. Ali Shamsadin, a wiry, gray-haired man who is also called Sheik Aloo by his men. Matter-of-factly, he lists the many roles his troops have played. The bodyguards for the interim government? Peshmerga. The Iraqi units that participated in the American assault on Fallujah? Pershmerga. The units that helped secure Mosul after it was all but overrun by the insurgents? Peshmerga.

"We want to play a role in helping to stabilize the country, but the Americans have sometimes been reluctant to let us carry out this role," he said in his large office at the newly built headquarters in the Fermandiya compound. As the Kurds are aware, not only is there serious internal Iraqi opposition to their taking on too many powers, but there is also a regional aspect. None of the three neighbors that abut the Kurdish area, Turkey, Syria and Iran, want to see either a strong or a independent Kurdistan, fearing that it would put ideas into the heads of their own Kurdish populations.

The head of intelligence in Kurdistan's Dohuk governorate, which borders Turkey and Syria, is adamant that much of the trouble in Iraq's adjoining Nineveh province, which contains Mosul, is being stirred up by the secret services of those countries. Sheik Aloo concurs and voices exasperation at American sensitivities, which he says have limited his ability to deal with the threats. But, he said, "lately it has become better and now we can operate more freely in Nineveh."

The 104th ING was sent down to Mosul in November when the insurgents threatened to take total control of the city. Brigade Gen. Muzaffer Derki is in overall command of four peshmerga ING units, the one in Mosul and three stationed in Kurdistan, but he spends almost all of his time with his men on the Al-Kindi base. A veteran of many battles with Saddam's troops, he talks about "the Arabs" in the same way his men do. "They need to be treated rough. You need lots of force when dealing with the Arabs. Otherwise they don't respect you -- they think they can rise up against you," he said, seated in a plush chair that he had his men bring out into the open air at a transportation base on the outskirts of Mosul. Wearing fatigues and bright orange shades as he lunched, he expounded on his views of the Arabs and explained why a seemingly innocent young man should be roughed up and be taken in for questioning.

"He is from a bad neighborhood where there are many terrorists," the general said. "We must talk to him to see if he knows anybody. If he is innocent, we will let him go."

The boy had been apprehended when the peshmerga unit had pulled in to inspect a disused army base in the "Hay al-Arabiyeh," the Arab quarter, in Mosul. They found five men in the grounds who had fled when the fighters approached. After a lot of firing, screaming, and punching and kicking, the five were led before the general, who set free four of them because they were Kurdish. The fifth was Arab, without doubt a terrorist, the Kurds said.

In the back of a pickup truck the accused terrorist sat sobbing into his blindfold. His name was Alaa, he said, and he was 16 years old. He lived with his parents in the insurgent-ridden Rashidiyeh neighborhood, but he said he had only come to the army base that day to buy bricks from the Kurdish family that lives next to it.

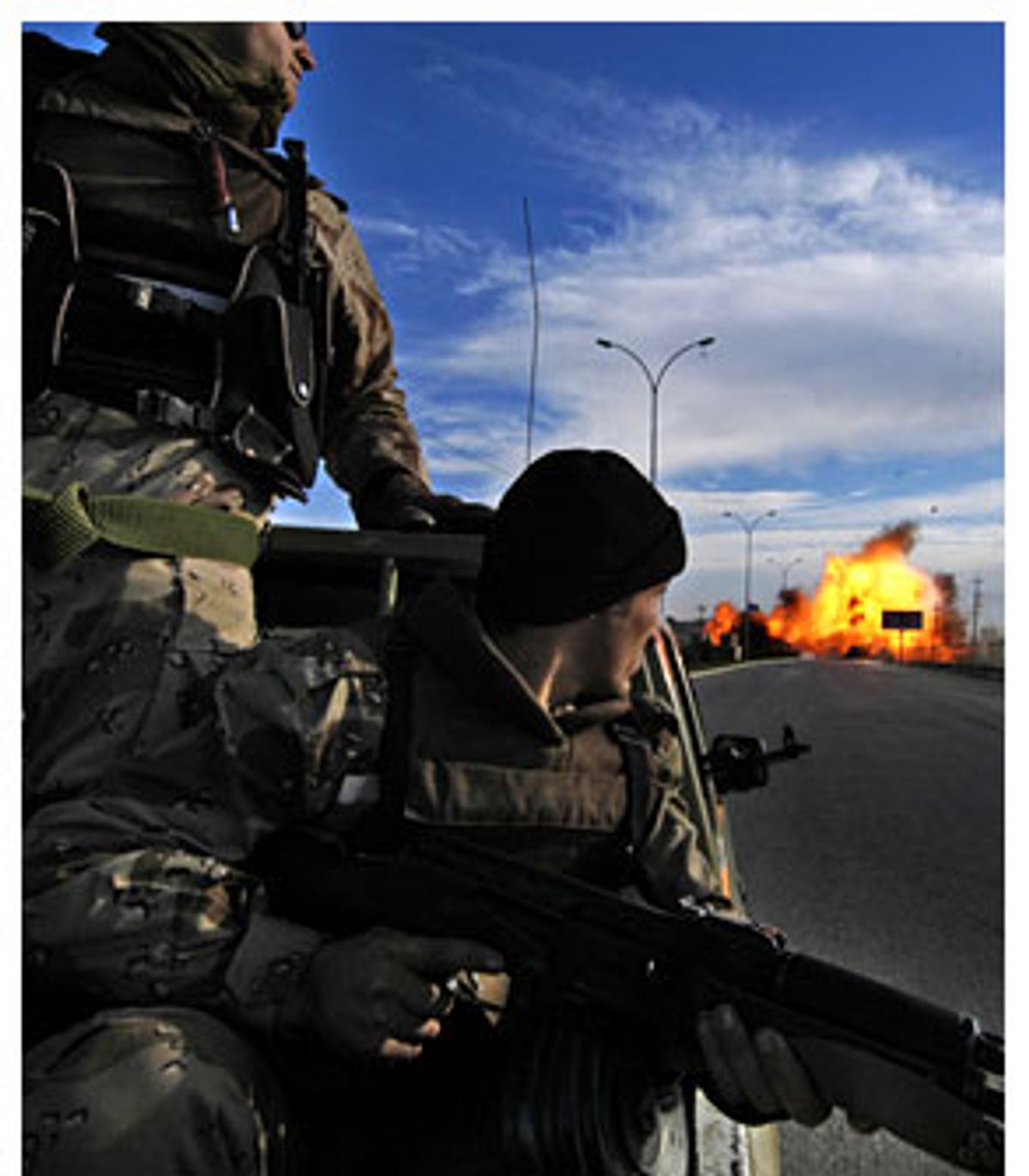

The Kurdish troops try to pick up as many Arabs as they can to help their intelligence effort. Because of the mixed Kurdish-Arab population of Mosul, they often get advance information of attacks. The same day, for example, Derki led his men back to the Al-Kindi base and received a warning at a checkpoint: A car bomb was on the road ahead. He decided to push on regardless. When a blue and white Toyota Land cruiser came into view, the nine-vehicle convoy simply crossed to the other side of the road. Seconds after the car carrying the general had passed, it was shaken by a huge explosion, and a large yellow and orange fireball seared the air. Everybody jumped out of the vehicle and threw themselves against a knoll as the heavy machine guns that were mounted on the peshmerga's pickup trucks opened fire on possible gunmen in the distance.

Derki stood up straight and calmly surveyed the scene. "Classical ambush, detonated by remote control, some shooting from the distance," he said as the whizzing sound of bullets filled the air. The ambush cost the lives of two of his men who had been traveling in a small bus, returning from leave in Kurdistan. Several of the peshmerga were covered in blood as they charged at the surrounding buildings. The Americans like the Kurds precisely because they are fierce fighters who do not wilt under fire. What they lack in organization, they make up for in motivation. The Kurds arrested two unfortunate Arabs, probably just bystanders, and proceeded to savagely beat them. The whole way back to the Al-Kindi base, they kept hitting the men with rifle butts and stomping on their heads with their army boots.

At Al-Kindi, the 104th is quartered next to the 101st, a battalion that used to be made up entirely of local Sunni Arabs. Even though many of the soldiers are now Kurds, the two groups do not mix. The men of the 104th speak with contempt about their brothers-in-arms in the 101st. "Stay away from them. They are Arabs and you can't trust them. But don't worry, we keep an eye on them."

Inside the 101st headquarters, the colonel who serves as deputy commander of the battalion said that most of the local men in the unit were intimidated and threatened by the insurgents. "Many signed up because they needed the money, but when they and their families were threatened they stayed away." He waved a list in the air with the names of 265 soldiers, about one-third of the battalion's strength, who deserted over the past 16 months. When the time came to confront the insurgents last November, the unit was no longer functioning.

The colonel said he was from a large and prominent Sunni family in the center of Mosul and did not want his name published. "They threaten to kidnap your children and burn down your house," he said. Several ING soldiers have been kidnapped and beheaded in Mosul. The videotaped executions were meant to scare off volunteers.

In the presence of a Kurdish officer, the colonel tried to sound understanding of the Kurdish position but did not quite pull it off. "Under Saddam Hussein, the Iraqi soldiers were taught to insult the parents in the presence of their children," he said. He should know, because he was an officer in the Iraqi army and was trained at the staff college in Baghdad. "Now that they are in charge, they take revenge for what was done to their parents," the colonel continued. "The weak become the strong."

Once outside, the Kurdish officer showed no sign of sympathy for the difficult position of his Sunni Arab colleague. "Yes, he runs a risk, but I still don't trust him. And he still has a choice, but you and I, we will have our heads cut off if his brothers get their hands on us."

Derki seemed to concur. Like his political bosses in Kurdistan, he made it clear he had no intention of ever letting Sunni Arab officers command him again. "These Arab officers, Kurds don't have to listen to them. Even the division commander is an Arab. But I only take my orders from the peshmerga."

Shares