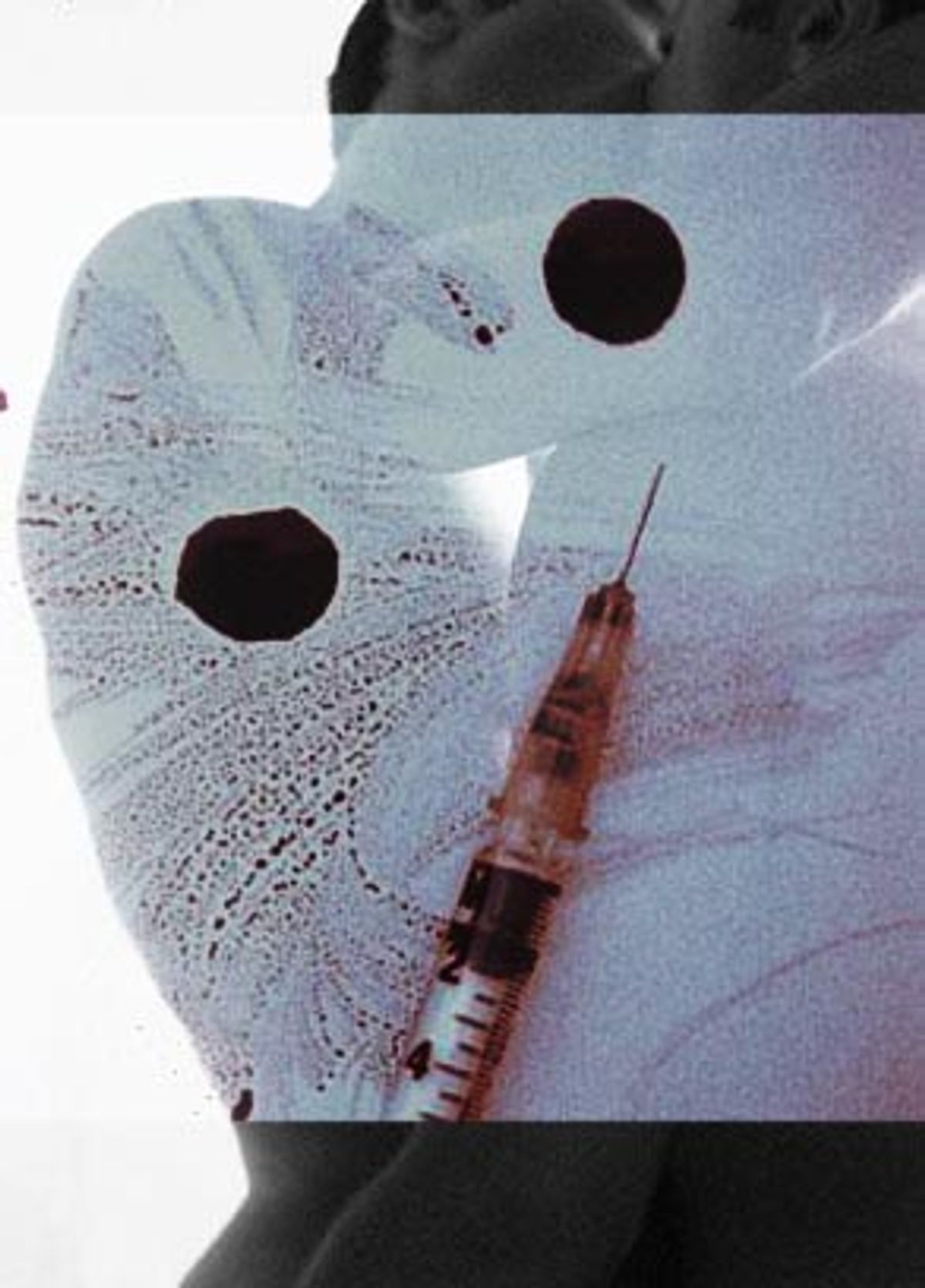

A week after the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene announced the discovery of a deadly new strain of HIV -- a discovery later questioned by AIDS researchers -- the initial alarm heard around New York City has died down. It has been replaced by an intense public debate among activists and health officials, as well as serious soul searching among New York City's gay community. Interviews with 15 gay men this week found that while these New Yorkers were worried about being exposed to the potential new strain, they were more concerned with the decline of safe sex and AIDS awareness in their community, especially among those most at risk.

For those old enough to remember the early days of the AIDS crisis in 1981-84, last week's headlines prompted a feeling of déjà vu. "There's a sense of, Goddamn it, why are people still doing this?" says Dan Cherubin, a 39-year-old librarian who works for a Dutch Agricultural Bank. "Seeing the news," he says by telephone, "made me think of Patient Zero in 'And the Band Played On,'" the first case of the "gay cancer" chronicled in Randy Shilts' landmark history of the AIDS crisis.

Cherubin has lived in New York all his life and remembers those days well. One difference between then and now, he says, is that in the early days of the epidemic the safe-sex message was ubiquitous. "I remember going to bars and seeing big bowls of condoms everywhere," he recalls. "At Gay Pride parades they'd just throw those things at you. You don't see that anymore."

Younger gay men, Cherubin says, have become complacent. He recently watched HBO's production of "Angels in America" with some friends who are in their early 20s. "They were shocked by the lesions, at the sense of being ill. They'd never seen what AIDS even looks like." And that, he says, scares him. "This is going to lead to someone not thinking about it."

"It's hard for my generation to put a face to the disease," says Matt Grieves, a 24-year-old medical student with brown hair and piercing blue eyes, sitting in Café Big Cup in Manhattan's Chelsea neighborhood. "How can you be afraid of hell if you've never seen Satan?"

Some say this complacency has spread with the cure. Since the development in the mid-90s of the retroviral drugs -- taken as a combination of pills commonly known as a "cocktail" -- AIDS has indeed become more manageable. And while patients have different reactions to the medications, most can keep up with their normal activities. AIDS experts and public health officials have long maintained that since the introduction of cocktails people don't see AIDS as the threat it once was and as a result have been less vigilant about practicing safe sex.

According to Sean Stroob, who founded Poz magazine in 1994 -- its mission was to "give back the possibility of survival to those living HIV" -- this learned complacency is "a problem with any kind of treatment. The more readily treatable [a disease is] perceived to be and the less invasive the treatment, the less fear. There's no question that fear motivates people's behavior."

"I was one of those people that had been lulled into the belief that AIDS was a manageable disease, not a death sentence," says Reggie Grayson, a 39-year-old co-owner of a New York design firm. But not anymore. The new strain, Grayson says, was a wakeup call. "I wasn't even aware I'd come to think of AIDS that way."

Grayson, who uses Web sites like Craig's List to meet men, has in the past week scrutinized online dating profiles much more carefully. "People have to write, 'Safe sex only.' It can't be vague in any way."

Likewise, when Carlos Ojeda, a 30-year-old agent at a modeling agency, first started dating as a teenager, he never asked potential partners about their status. "You figured people would have the common decency to tell you." But this, he discovered, is not always the case. "I'd met this guy through a friend. We hit it off and started seeing each other. I was waiting for the right time to be intimate. He was just as patient, which was odd. The day finally came. He told me after the fact that he was HIV positive. Luckily we'd had safe sex."

It took John, an editorial director with a retail fashion house, who didn't want to use his full name, years before he got into the habit of practicing safe sex. Having been a 21-year-old house boy (providing light cleaning and sexual favors) on Fire Island in 1979, he remembers a lot of fun before AIDS came into the picture. But even after losing a friend very quickly to AIDS in 1981, he still took risks. Then in 1988 John's brother got sick with AIDS and in the mid-'90s was "snatched from the jaws of death" by a progressive doctor who got him onto the cocktails. "At this point we were all practicing safe sex."

But something interesting happened in recent years. John, who today works as an editorial director for a retail fashion house, says he's witnessed a rebirth of sex parties "not seen since the '70s." And in the late '90s he started bare-backing (having anal sex without condoms). "Of course it was stupid," he admits, "but when I did it I thought, This is really hot and maybe it's not so scary. I'm having sex with someone who looks really healthy." At the time he was taking meth and using the Internet to organize parties. "That was a compartmentalized part of my life."

Many of the men interviewed by Salon said that the use of methamphetamines often impaired their decision making and said that fears about the new strain would make them think twice before using again. Alternatively known as crystal meth, speed and tina, methamphetamines have surged in popularity in the last few years. Health officials say that in addition to lowering inhibitions and increasing incidents of risky behavior, the continued use of meth breaks down the body's resistance.

"Meth takes over your body, and you become a sex-hungry monster," says Ojeda, who used meth recreationally for four years. "You'll have sex with anybody and anything. When you're that high you don't care." Ojeda quit using the drug five years ago, and is now so careful he's almost paranoid. "I won't go down on anyone anymore," he says. "I won't even kiss someone if their mouth looks weird."

Meth first gained popularity on the West Coast in the late 1990s -- in cities like Seattle, San Francisco and Los Angeles -- where it fueled all-night dance parties in clubs in much the way Ecstasy and cocaine did in the past. But in recent years the drug has taken hold on the East Coast, where it plays an integral role in many anonymous sexual encounters, especially those arranged online. On sites like Craig's List, AOL, Manhunt.net and Gay.com, men can anonymously seek out one-on-one or group sex and can specify whether they want to PNP -- party and play (do drugs and have sex) -- or not. A typically pithy posting on Craig's List reads: "must travel, groups a plus. looking to pnp. pics for pics."

Brian McConnell, a 34-year-old software developer, blames the combination of meth and the Internet for the possible emergence of a new super-virulent strain of AIDS. McConnell spends half the year in New York and the other half in San Francisco, and observes dating habits on both coasts. "I wasn't surprised," he says of the news that a new strain had come to town. "Before the Web, [speed] was used in a social context. People had to leave the house to get laid and had to be presentable in public to do so. The Internet changed all that, and now speed is a very anti-social drug, with most users spending their time trolling the Web for sex and more drugs."

McConnell says that while news of a super-virus might prompt some people to change their habits, the people who pose the greatest danger to others are the least likely to change. "Everybody I know from my peer group is negative except for the people that got into crystal. All but one of them are positive." McConnell not only refuses to use meth himself, he won't hook up with anyone who does. "Once you know what to look for -- fidgeting, rapid speech, grinding teeth -- you can spot it a mile away." He laments that his new rule "eliminates a large percentage of the dating pool," but he'd rather stay healthy.

Asked whether he thinks crystal meth plays a part in the rise in infection, Stroob says, "It is a factor," but adds, "It's not as big as a factor as our failure to give appropriate information to people." According to Stroob and many others working in the field, the greater challenge to curbing HIV infection today is the conservative political environment, which pushes abstinence-only education, content restrictions on prevention materials, and funding cutbacks.

George Ayala, director of the Institute for Gay Men's Health at Gay Men's Health Crisis, argues that the Center for Disease Control and Prevention doesn't address the needs of the groups most at risk for infection. "You are asked to choose from a list of 16 prepackaged interventions. Of those maybe four address gay men," he says, referring to the template workshops and training sessions funded by the CDC. "And if you're of color only one addresses gay men."

Carlos Nietos, a 40-year-old doctor with a heavy-set build and closely cropped brown hair, sitting in Café Big Cup, said when he first heard about the super-bug through a friend, his initial reaction was, Oh no, are we back to those days? When he was a medical student in the mid-'90s, treating young people with AIDS was "soul-wrenching," he says. But where AIDS patients used to be the center of his life, he now goes days without thinking about AIDS as a killer. "You feel better being a peacetime doctor than a wartime doctor."

Nietos thinks that even if news of a drug-resistant, fast-acting virus does succeed in making people more cautious, "there's something else operating that makes certain people seek out and enjoy taking risks. I don't understand it."

Christopher Carrington, a professor of sociology and human sexuality studies at San Francisco State University, is trying to understand it. Carrington, who's working on a book called "Circuit Boys," a book about sex parties, is finding that many gay men engage in what he calls "negotiated safety." If a man's considering having unprotected sex and is choosing between someone he knows nothing about and someone he knows is HIV positive but who has a low-viral count, he'll go with the man with the low viral-count. 'They're taking risks, but they're calculated risks," Carrington says. "Sex is a very important benefit. That becomes part of the calculation."

Asked whether he thinks news of the super-virus will change people's behavior, Carrington answers, "It might change. But it might not be positive change. When these kinds of announcements occur and there's no real epidemic that follows, people begin to doubt the messages that are coming out. That's what's dangerous."

Shares