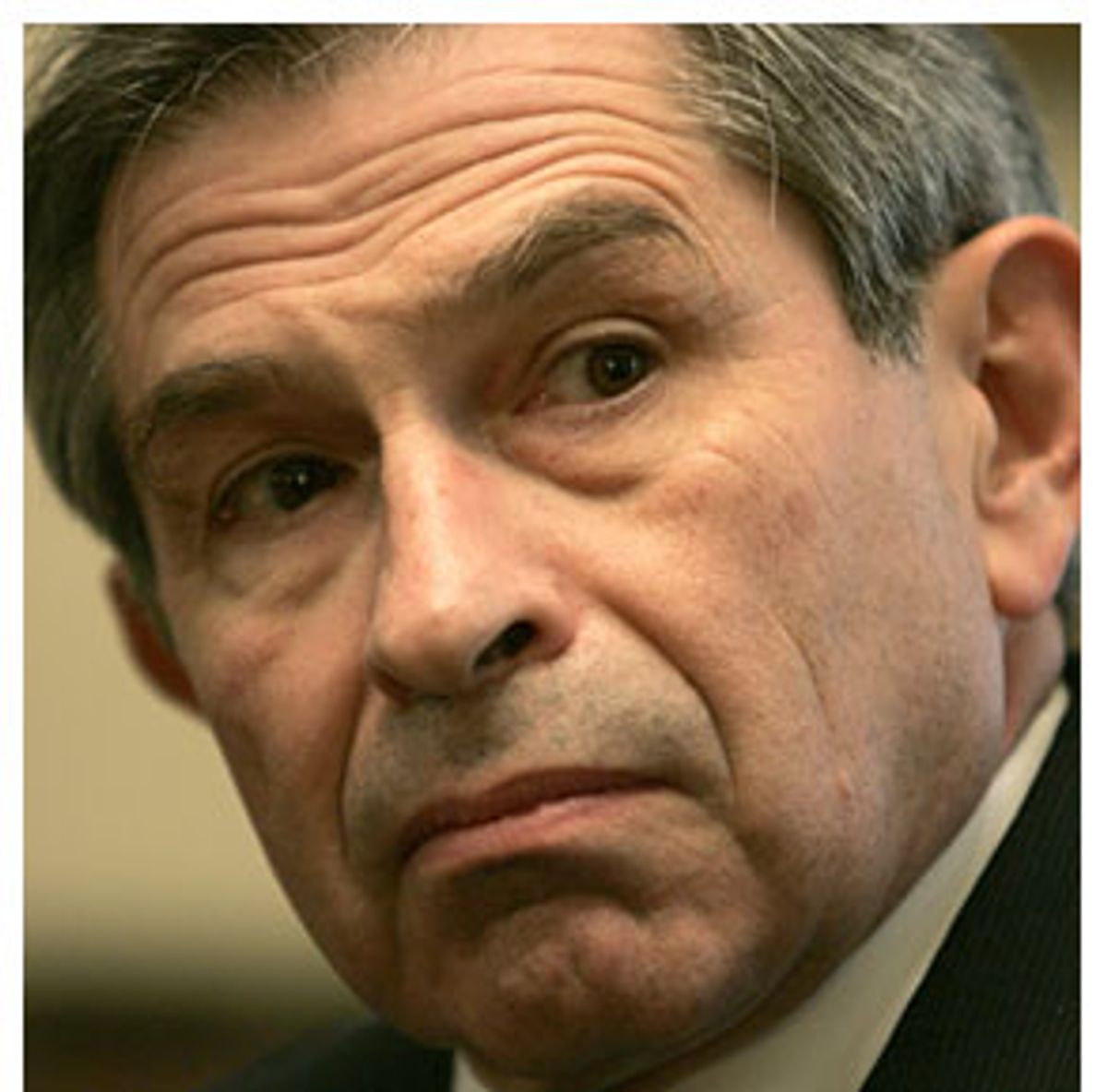

In announcing his nomination of Paul Wolfowitz to head the World Bank on Wednesday morning, President Bush offered two main reasons why foreign leaders should support the deputy defense secretary's bid. The first is that Wolfowitz is a good manager. "The World Bank is a large organization," Bush pointed out, just as "the Pentagon is a large organization." In other words, if Wolfowitz can manage the generals, he can certainly manage a bunch of bankers. Almost as an afterthought, Bush added a second thing Wolfowitz has going for him: "Paul is committed to development," he said.

It's possible that Bush is right on the first score. However dimly you may view his ideological and foreign-policy goals, it's likely that Wolfowitz's management experience at the Defense Department, which is an order of magnitude larger and more complex than the World Bank, has prepared him well to oversee that agency. But Bush's second argument, that Wolfowitz is interested in aiding the developing world, came as a surprise to experts in the field. If Wolfowitz has an interest in reducing poverty in Africa, Asia and Latin America, for example, global development experts have been unaware of it.

"I have looked for evidence of Mr. Wolfowitz having development goals -- I have tried to find it in his speeches, and I have not been able to," says Jeffrey Sachs, the Columbia University economist who heads the U.N. Millennium Project to reduce global poverty, hunger, disease, illiteracy, environmental degradation and gender discrimination by 2015. Neither, Sachs points out, does Wolfowitz have any professional qualifications for the job -- he's not an economist, nor a banker (as is the bank's current president, James Wolfensohn), nor a doctor who knows about fighting disease, nor an agronomist who can combat the developing world's food shortages, nor an environmental scientist who can assess how global climate change might affect the world's poorest nations. It's true that Wolfowitz has been a diplomat, which probably isn't bad professional experience for an organization that's frequently criticized by many nations across the globe. But one takes little comfort in knowing that for all his shortcomings, the World Bank will at least be winning the diplomatic expertise of Paul Wolfowitz.

During all of the posts he's held in his professional life -- in academia, at the State Department during the Reagan years, and the Defense Department during the first and second Bush administrations -- it's hard to find a single instance in which Wolfowitz has put international development anywhere on his list of global priorities. Sachs has worked on international development issues for more than two decades, and he knows pretty much everybody in the field. Wolfowitz, he says, "is not known in this field as having any role." Search Wolfowitz's official biography on the Defense Department Web site for words like "development" or "poverty" or "malaria" or "AIDS" or "debt" or "economic policy" and you come up with nothing. The document suggests that Wolfowitz has spent more time thinking about how to position naval ships than how to deploy bed nets to nations afflicted with malaria.

In "The End of Poverty," his engaging new book that outlines specific ways to dramatically reduce global poverty, Sachs points out the difficulty of diagnosing why certain nations fail to prosper while others succeed. Sachs writes that "it has taken me 20 years to understand what good development economics should be, and I am still learning." So, too, he says, are professionals at organizations like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, which have committed grievous missteps in their aid efforts over the years. In short, international development is not easy; understanding what you're doing takes years of dedication, even if you have a Ph.D. in economics, as Sachs does.

Not every president of the World Bank needs to have a doctorate in economics, certainly, and there have been others -- Robert McNamara after his stint as Defense Secretary in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations -- who've come straight from the Pentagon. But professional expertise is especially required right now, Sachs says, because we're on the brink of actually making things a lot better in the world. If organizations like the World Bank and the IMF do things right, we can end extreme poverty by 2025. But if they fail, history won't look on us kindly.

And just about any other nominee would be more likely to succeed in the job than Wolfowitz. Even pie-in-the-sky suggestions like Bill Clinton and the rock star Bono seem better equipped for the job -- at least each of them (unlike Wolfowitz) has expressed deep concern for those suffering in developing nations. In the foreword to Sachs' book, Bono writes movingly of the plight of the poor. "If we're honest, there's no way we could conclude that such mass death day after day would ever be allowed to happen anywhere else," he says of the statistic that 15,000 Africans die each day from AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis.

These global ills "are not amateur-hour issues," Sachs says. "We presumably wouldn't nominate Wolfowitz to be surgeon general. We wouldn't send him to the Supreme Court to argue a case. He's a defense specialist. This is not a qualification to be the head of the World Bank."

Sachs worries, though, that Wolfowitz's poor resume may not matter much in the selection process. He wishes that other nations would offer alternative nominations, but he says it's likely that Bush's choice will win out in the end, given the United States' longtime influence over the World Bank.

Shares