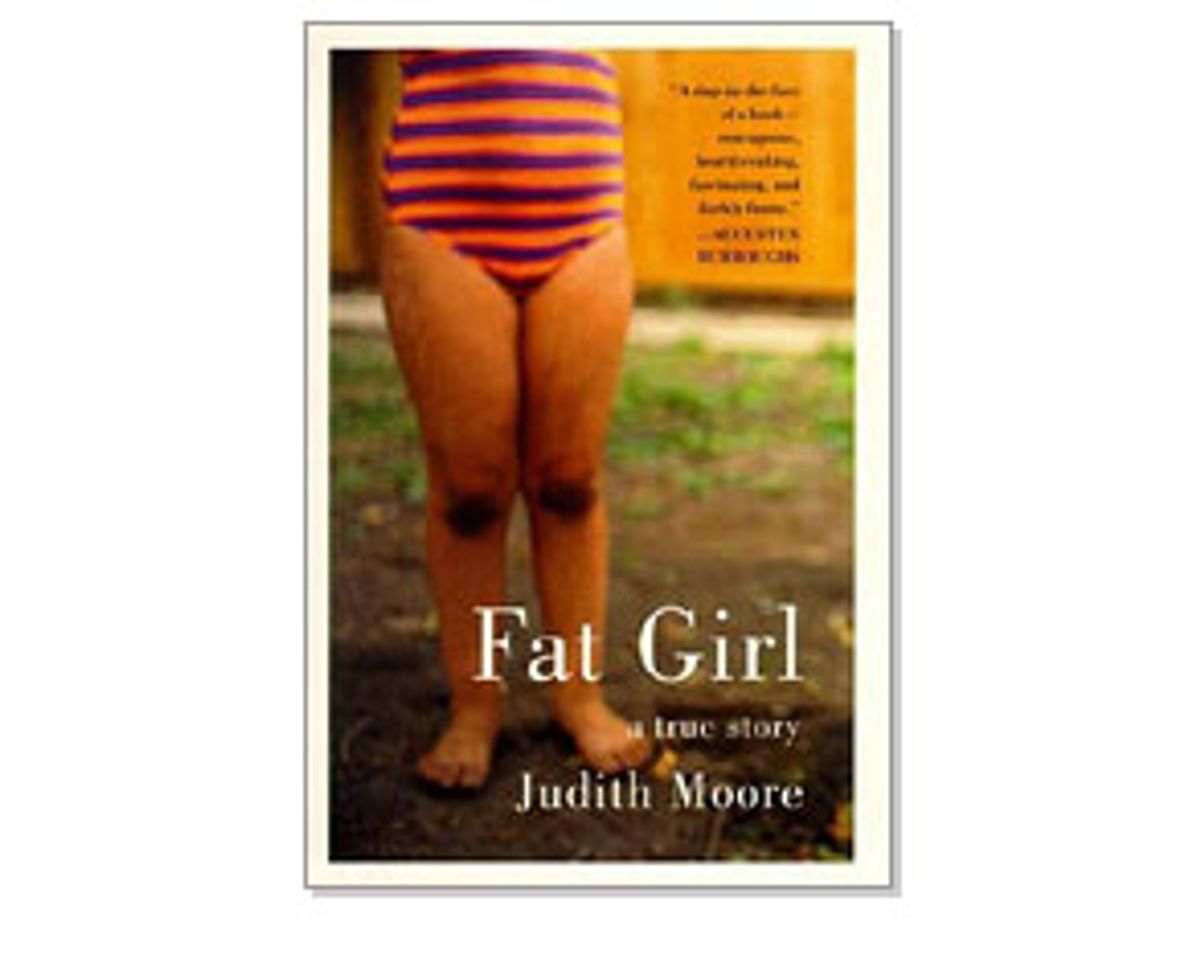

Judith Moore does not want your pity. From the very first line of her new memoir, "Fat Girl: A True Story," Moore's purpose is clear, her voice steady and unforgiving. "I am fat," she writes. "I am not so fat that I can't fasten the seat belt on the plane. But, fat I am ... All I will do here is tell my story. I will not supply windbag notions about what's wrong with me. You will figure that out. I will tell you only what I know about myself, which is not all that much."

While Moore's intentions sound simple, the story that emerges in "Fat Girl" is layered and complex. Hers is not a self-help book, nor an inspiring diet guide. Instead, in spare and often piercing prose, Moore bares the ugly truth about her past as an obese child starved of love, a ravenous "wild animal" of a girl who ate to fill the hole left by an absent father and an abusive, vindictive mother. Moore, whose previous memoir, "Never Eat Your Heart Out," also used food as a lens through which to examine pivotal moments in her life, again appraises herself -- and her flawed, fractious family -- with ruthless candor. "Fat Girl" chronicles what it felt like to weigh 120 pounds in the second grade, to be ridiculed by her only grandmother, and to repeatedly break into her neighbor's home to empty the refrigerator.

There seems to never have been a time when Moore has not been both repulsed by her own body and obsessed with it -- which itself is a heavy weight to bear. But between the pages of "Fat Girl," it is Moore's consuming self-hatred that is exposed and finally, painfully purged. Read an excerpt from Moore's memoir below.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

My mouth is dangerous. My lips and my teeth and my tongue and the damp walls of my cheeks are always ready. My mouth wants to bite down on rough bread and hot rare peppered steak and steamed broccoli sprayed with lemon juice. My mouth wants my maternal grandmother's biscuits and sunny-side-up eggs, whose gold yolks rise high above the white circles. My mouth wants potatoes sluiced with gravy and Cobb salad and club sandwiches and ridged potato chips and loathsome onion dip made with sour cream and dry onion soup mix.

When I walk through the kitchen -- when I walk through the world -- my mouth is on the prowl.

I am frightened of food. I flinch when I consider ice cream, especially flavors beyond strawberry, vanilla, and chocolate. Caramel macadamia crunch might as well be the A-bomb, I am so scared of salty nuts and unctuously sweet caramel. I am scared of the frozen cream that melts along my tongue and walls of my cheeks.

The two couches in my comfortable living room are upholstered with a dark gray fabric. On the skirt of the couch where I most often sit is a stain darker than the upholstery. I never see this stain without thinking of a terrible night.

I could not sleep. I wandered the lightless apartment. Lily the Dachshund, an exceptionally long roan-red dog with an exceptionally long tail, wandered behind me. I opened the freezer and took out a pint of strawberry ice cream and a round-bowled sterling soup spoon and sat on the couch in the moonless dark. Lily the Dachshund, fond of ice cream, nuzzled at my bare feet with her cold black nose.

I sat at the edge of the couch, legs slightly apart. My elbows were on my knees; I was hunched and full of sorrow. I wore a loose cotton nightgown. My breasts hung down inside the gown and swayed. I spooned into my mouth the first chilly strawberry dollop. Cream melted on my tongue, which didn't take long, because the ice cream was soft. I spooned in another bite. I wanted to say to the ice cream, "I love you." I wanted to say, "You are my mother." I wanted to whimper, "Mama, Mama, Mama." I wanted to weep.

I spooned out the last bite for Lily. The ice cream, by then, was runny. As I put the spoon into the empty carton so that Lily could lick it, ice cream dribbled down the couch's skirt. That dribble's what stained the couch.

I am scared of the big, hot hole my mouth is. My mouth always wants something and most of what my mouth wants, I can't give it.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

When I was in first grade no one paid much attention to me. I was occasionally teased. Mostly, I was ignored. No one talked to me at lunch and rarely did anyone allow me to join in a game at recess. Right away, in second grade, a group of older boys took after me. Out on the playground, after lunch, they circled me. They yelled, "Fat girl! Fat girl! Fat girl!" They sang, "I don't want her, you can have her, she's too fat for me." I saw the hairs in their noses, they got that close. I smelled boy BO.

The meanest was Dean, who every day wore brown plaid pants. He was the showoff of the bunch and he put his hands on his hips like a dancer and wriggled back and forth while he sang "I don't want her, you can have her, she's too fat for me." The others sang with him, off-key in pure boy soprano.

I never knew what to do. I stood and stared while their mouths opened and shut, while the hard dentals of "don't" and the soft labial "you" spit and slid from their mouths. They had baby teeth missing. We all did. Wide gaps where our square rabbit teeth would soon drop down.

Rodney, who was one of the most hateful boys, especially liked to poke a finger in my rear end, which in Brooklyn they called your heinie. He was a fourth-grader. He would breathe right down on me and stick a finger right between my buttocks and push and push. He had liver lips and his breath gave off a bubble-gum smell. He would put his liver lips right on my ear. One day he said the worst thing to me. He said, "I bet you'd eat my shit." Rodney also would come up to me on the playground and push me against the chain-link fence. When he got me pushed hard against the fence he would rub his hands over my huge stomach and ask me, "You got a baby in there, Fatso?"

Other times Rodney put his hand over my mouth and crushed my lips against my teeth and with his other hand touched the area between my legs that Grammy had called my "business." Finally one day I got my mouth open and bit his hand. He slapped me hard and said, "Maybe your ma should put a dog muzzle on you."

I told no one. I said not one word about my chafed thighs, about Rodney and his friends.

The fatness was my problem.

People said when I was a child that inside every fat person a thin person longed to pop out. I did not believe that. I believed that inside every fat person was a hole the size of the world; I believed that every fat person wanted to fill that hole by eating the world. It wasn't enough to eat food. You had to swallow air, you had to chew up everyone who got near you. No wonder, I thought, that nobody liked me or liked me all that much. I was like the wild animals in my Homes and Habitats of Wild Animals book who spent their lives hunting down other animals and eating them raw. Nobody much liked me, I thought, because they sensed that I wanted to bite into their bare arms and bare cheeks and rip off chunks of them and chew and chew and swallow. I wanted to eat them not because they looked particularly tasty or even because I was hungry, but because I was empty and I needed to feel full.

I built walls of fat, and I lived inside. When those boys said fatso, fatso at me what they said almost, but not quite, bounced off my fat walls. When my mother walked to her sewing machine and took out of its drawer the belt she kept coiled there and came at me with it, the belt went thud against the fat. The belt didn't cut as hard as it might if I were skinny. But if I were skinny would she have hated me so much? If I hadn't had fat arms like an old lady's maybe my mama would not have beat me so hard, or maybe she would not have beaten me at all. Maybe she would have looked at me and purred, "I love you, darling. I love you."

I looked out my fat-house windows onto the street along which passed thin people, pretty people, popular girls and boys. I was trapped in my fat house. But I was happy in my fat house. I built my house walls with cream gravy and Peter Paul Mounds and Baby Ruth and Mellomints. Inside, my house stayed cold and damp and empty. I had no furnace, no wood stove, no fireplace, no space heater, no clanking radiator. My house was cold.

I squatted down inside my house of fat. Sometimes I said prayers. Sometimes I sang songs. I was a little singer. I wanted to sing my way out of this house of fat. But mostly what I did was wait. I waited for my father, waited to look up into the kindly face that smiled down as the sun did when clouds parted. I waited for my father to take my hand and say, "My little girl. I am taking you away from all this."

Once I arrived at my father's home I had slender legs and slender arms and a flat bony chest. His new wife said, "How cute your little girl is!" We were dancing, he and I. We were kicking up our heels.

This never came true. This was what my mother called "wishing" and when I wished something, she said, "If wishes were horses, then beggars would ride." I hunkered down inside my fat house. I listened to wind shift branches against my fat-house walls. I listened for a voice that would whisper, "I love you." I listened in vain.

I waited for a knock at the door, a ring of a bell, a tap on the window, a shadow on the walkway.

I didn't eat all that much to get myself so fat. Sometimes I even stayed right on the reducing diets and did not cheat and did not steal nickels for Mounds bars and I still didn't lose much weight. All I was was so hungry that I would be dizzy and feel like the wind would blow me away or that I would fall down like movie ladies did in a dead faint and need smelling salts. I seemed to be able to inhale, and with each inhalation I expanded like a balloon.

I was filling up on the world. It wouldn't give me anything; I would eat it alive, its air, its trees, its houses, its people. Grammy was right; I was Man Mountain Dean. I would start with my family, then our furniture -- the couch, the bed, the dishes, the family photographs in the shoe box -- and then I would rub my huge stomach and walk down the sidewalk that led to our now-consumed house and I would start on passersby, would lift them up by the scruff of their jackets and pop them into my mouth like cool pale green seedless grapes.

I hated everyone and yet I wanted everyone to love me. I stood at the playground edge. I watched girls on swings. They had thin legs and pulled their white socks up high on their slender calves. They sailed high, long hair flying behind them. Smiles creased their faces and they opened their eyes wide. I watched boys watch these girls. I knew boys never would watch me this way. I knew they wouldn't chew a grass blade end and narrow their eyes and study my slender legs. I would never have long slender legs. I wanted to be invited to thin girl birthday parties. I wanted to see the cake their mother carried to the party table. The thin girl's mother decorated the thin girl's cake with pink rosebuds heaped one atop another. I could smell from far away the sweet frosting, the strong burning sugar scent.

I loved the boys, even my tormentors. I loved their plaid jackets, zipped up to their scrawny necks, and I loved their home-done haircuts. I loved the salty pork smell these boys gave off when they walked from the windy, cold playground into the steam-heated classroom. I sniffed at them as I sniffed at dinners cooking on the stove.

How could I get them to love me? I was at a loss to figure this. I tried. When girls clutched together near the merry-go-round, I dared myself to stride across the asphalt toward them. I dared myself to make myself a place in the circle they formed. I can still feel the smile form on my full-moon face. I see how I must have looked. I was as sizable as some of their mothers. I weighed more than some of their mothers weighed. I sensed their disgust. I did not want to believe what I felt.

Reprinted by arrangement with Hudson Street Press, a member of Penguin Group.

Shares