Yasser Arafat's gravesite is effusive. The plot is an explosion of color: a garden of flowers and rose wreaths, of ribboned banners from around the globe proclaiming respect and sadness for the deceased Palestinian president. A mausoleum of glass shields the site from weather, and three guards flank the grave day and night, keeping stern vigil over their patriarch. At the foot of the site is a Quranic verse: "God will give victory to believers."

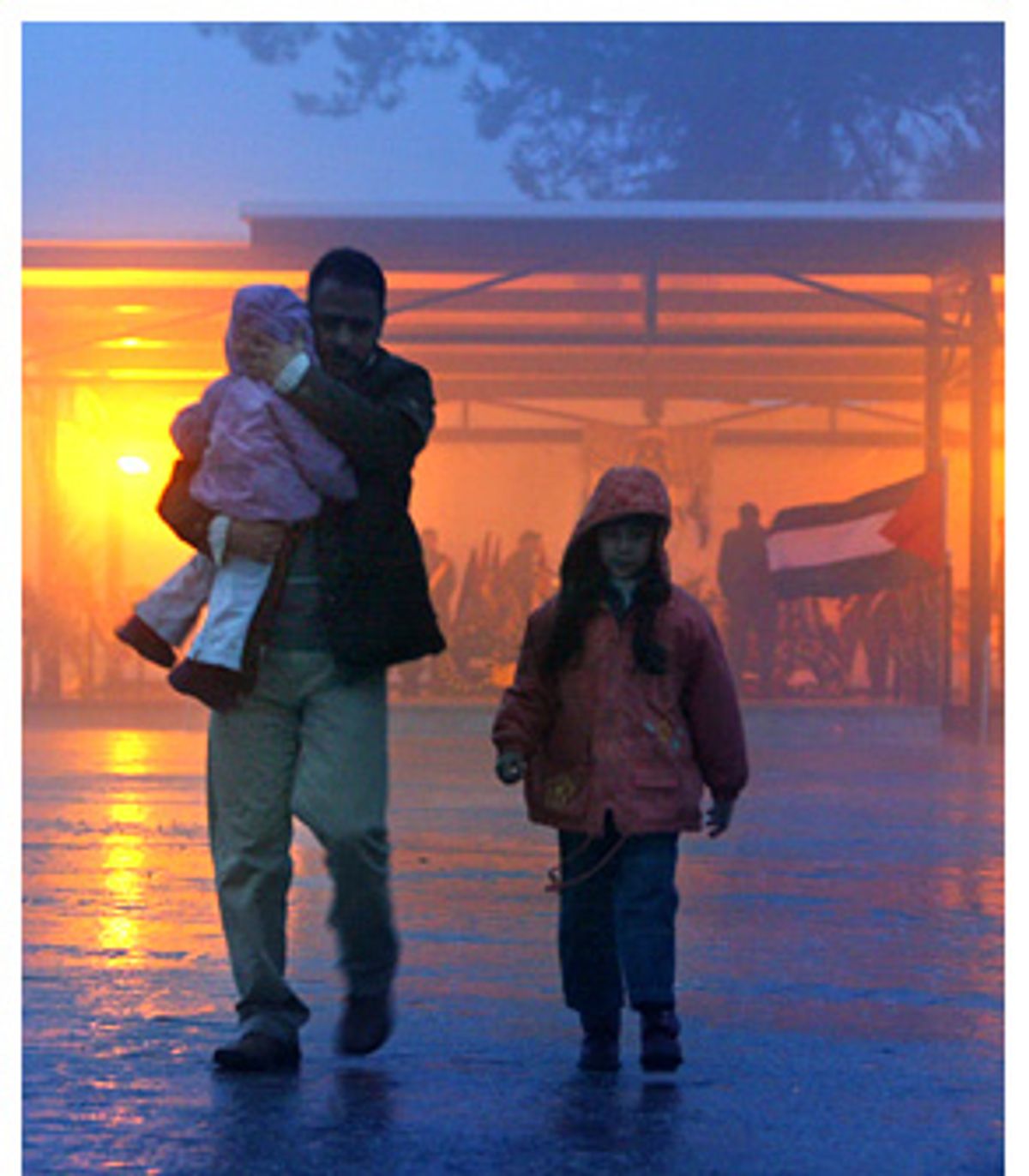

Though the gravesite, in the West Bank city of Ramallah, aims to exalt Arafat, it is a lonely place. Arafat died on Nov. 11, 2004. Three months later, on the afternoon of my visit, I saw few mourners. Those who did come paid their respects to the rais, as Arafat was known, and then drifted away, as quick and quiet as ghosts. The grave's location adds to its isolation: It's tucked into a far corner of the Muqata, the Palestinian presidential compound. The Muqata, the former British military headquarters from the old Mandate days, is an enormous expanse, but a virtually empty one. In 2002, after a series of Palestinian terrorist bombings killed dozens of Israelis, the Israeli army reoccupied Ramallah with the goal of destroying the city's terrorist infrastructure, smashing the Palestinian Authority and isolating Arafat. This incursion, part of a massive military campaign in the West Bank code-named "Operation Defensive Shield," destroyed most of buildings inside the Muqata. Today only two modest structures remain; the rest is pavement. Operation Defensive Shield marked the beginning of Arafat's confinement: After it, Israel forbade him from stepping beyond the front door. In this sense, Arafat's grave is as isolated from the life of Palestine as the Palestinian leader was himself during the last two years of his life.

Many people feared Arafat's death would set the Palestinian people dangerously adrift. He was not simply their national leader, but the symbol of Palestinian nationalism -- the embodiment of his people's aspirations for statehood and the man who brought them recognition from Israel and the world. More than this, Palestinians are a nation besieged by occupation and fractured by internal divisions: between West Bankers and Gazans, Muslims and Christians, insiders and outsiders, refugees and non-refugees, and scores of political factions. Without their keel, their stabilizing force, surely this nation would capsize.

Except it hasn't. Palestinians are looking toward the future with apprehension and even fear, but they are not in shock and they are not adrift. They found themselves without a captain and wasted no time in plotting a course for themselves. How effectively they navigate this course remains to be seen, and the actions of Israel and the United States will have a decisive effect on the outcome. But in the meantime, one thing is certain: Arafat may be immured beneath the Muqata, but his people are struggling to move on.

"In the past there was a national consensus about Arafat and his role as a national leader," Jabril Rajoub told me a few weeks ago. Former chief of security in the West Bank, Rajoub now serves as national security advisor to Mahmoud Abbas (better known by his nom de guerre, Abu Mazen), Arafat's successor. "There was always conflict between the old and young generations when Arafat was alive," Rajoub continued, "but Arafat controlled the rules of the game. With his death, the conflict is going on with new momentum."

Rajoub was referring to the long-standing division within Palestinian politics between the old guard and the young guard. The former describes the founding members of Fatah and the PLO, men who lived in exile with Yasser Arafat in Lebanon, Jordan and Tunis. Many of them were elected to the Fatah General Assembly in 1989 and occupy positions in the Fatah Revolutionary Council as well as the Fatah Central Committee, the movement's most powerful body. The young guard lived in the territories under Israeli occupation and won legitimacy among the people as fighters in the first intifada and as prisoners in Israeli jails. Though they shared ideological and operational links to the PLO (all based on armed resistance against Israel), the young guard were like orphans, forced to come of age without the guidance and protection of their parents.

The young guard, however, had a set of surrogate parents: the Israelis. Palestinians in territories may have learned occupation from Israel, but they were also exposed to Israel's democratic system of government.

"We learned democracy from Israel," one Palestinian woman told me. "If you discount Israel's treatment of the Arab Israelis (who are subjected to a great deal of de facto, and a certain amount of de jure, discrimination), they still have regular elections, parties, a working parliament. Even when we were under occupation we saw this."

That Palestinians in the territories understood and appreciated democratic ideals was evident in their universities and inside Israeli prisons, where elections were institutionalized and meticulously conducted. In contrast, the old guard developed their view of power and governance under the corrupt and dictatorial Arab regimes in which they were living.

This was not simply a question of rampant corruption but what many have called a crisis of administration within Arafat's Fatah party. Sami Sa'adi, president of the Cairo Amman Bank, explained it this way: "There is no clear mechanism inside Fatah to give the new generation a role in decision making. No clear channels between the top leaders and the ground. We need modern institutions: transparency, elections, rules to define membership in Fatah."

Sa'adi, who is in his mid-forties, spent his teenage years fighting the occupation and his early adult years in an Israeli prison. After his release, the Israelis deported him for his activism in Fatah. Sa'adi received a business degree in Egypt and upon graduation, the Israelis permitted him to return to the West Bank. He worked for the Palestine Development Fund and the Palestine Banking Corp. before assuming his position at Cairo Amman. In his sober suit on the top floor of a bustling bank, Sa'adi looked like a man who understood the workings of a modern institution. "The requirements of making a secret organization," he continued, "are not the same as making a public organization."

The first ten years after Fatah's establishment in 1958 was a precarious time for the movement. Arafat and his close associates, Saleh Khalaf and Abu Jihad, were being pursued by Israel and others for their terrorist activities in the Middle East and internationally. They were constantly only the move -- during this period, Arafat is said never to have slept in the same bed twice -- and their activities were highly centralized. The top leaders of the party today such as Abu Mazen, Abu Ala, Hani Hassan and others were not active in Fatah's military branch (Khalaf and Jihad were eventually assassinated by the Israelis), but the party's culture of elitism and secrecy has survived. At least until Arafat's death.

"After his death everything is defined," Sa'adi said. "We are approaching a new era of our modern history. Arafat was a patrimonial leader. Because of the significant efforts he made for the cause he had special respect. Now nobody has the same power. Now all of us are equal."

Sa'adi is so certain the political culture in Palestine is changing that he has considered resigning as president of the Cairo Amman Bank and reentering politics. He's not the only one. Sa'adi says he knows many Palestinian professionals who had distanced themselves from Fatah because of its corrupt and elitist culture but who are leaving their jobs to return to politics. "There will be a very big cost for myself and my family in our standard of living," Sa'adi acknowledged, "but I think it's time. There is now hope to make some change within Fatah."

The newly elected Palestinian prime minister, Abu Mazen, had alerted me to the prospects of such change. I visited him in February, two days after his return from Sharm Al-Sheikh, where he and Ariel Sharon agreed on the principle of a cease-fire. We met inside the Muqata, across the concrete expanse from Arafat's grave.

Abu Mazen has none of his predecessor's revolutionary flair. He wore a suit, not a general's uniform, and his gray hair was neatly combed -- no kaffiyeh. Abu Mazen was a founding member of Fatah and secretary-general of the PLO Executive Committee, and he led the secret negotiations with Israel that took place between the 1991 Madrid conference and the 1993 Oslo Accords. I asked him about his new role as leader of the Palestinian nation.

Abu Mazen, who is 69, leaned forward in his chair and looked at me intently. "It is time to hand the younger generation the flag," he said. "We are 60, 65 -- 70 years old!" The way he said it, he sounded surprised that one as old as he was sitting in the presidential chair. "We started in politics at your age," he winked at me. "It is now time to move on."

Abu Mazen illustrated this conviction a few weeks later over the question of cabinet appointments. Initially, Palestinian Prime Minister Abu Ala (Ahmed Quereia) proposed a cabinet full of former Arafat loyalists, but the Palestinian Legislative Council voiced such intense opposition to Ala's nominees that Abu Mazen stepped in to compile a new cabinet list. Of the 24 positions, 17 of his appointees are new to the cabinet, and nearly all of them are experts in their fields of responsibility. For example, Nasser Al-Kidwa, former PLO representative to the United Nations, replaced Nabil Sha'ath as foreign minister. Sabri Saidam, the new minister of technology, holds a Ph.D. in electrical engineering, and the agricultural minister, Walid Abbed Rabbo, received his Ph.D. in human resource management. Abu Mazen chose these ministers from a list of 100 professionals and did so in close consultation with Fatah legislators. By contrast, Arafat appointed his cabinet -- loyalists with little technical expertise -- behind closed doors.

Though this is a positive step, Abu Mazen faces serious challenges: foremost, the problem of corruption. Corruption runs through Fatah -- and not only the members of the old guard.

"It's about thinking, not age," explained one Fatah activist who asked not to be identified. This activist has worked for a number of high-level security officials in the Palestinian Authority, men who are considered part of the young guard but who, as he says, "are the most corrupt people you will see. They can be from Tunis or Nablus," this activist continued. "What matters is whether they put their personal agenda before the national agenda."

Kaddura Faris, a young guard member of the Palestinian Legislative Council, agreed. Abu Mazen, he said, is technically old guard. "But he's serious, very clear. He doesn't use a lot of symbolism." On the other hand, many members of the young guard who fought against the occupation and served time in jails see themselves as symbols of resistance, and it makes them feel invulnerable. "If a young man is arrested for stealing a car," Faris explained, "the police will receive many calls to release him because he's a fighter, part of Fatah, or because his brother is a martyr ... We have to have an accountable culture. When the people in the government respect these laws, the people will understand."

Khalil Shikaki, head of the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research (his office was once ransacked by Arafat goons for releasing some information that the rais did not like), took a more sobering view. "Abu Mazen is a member of the old guard, and even if he has good intentions, he's been socialized in this political culture for the last 50 years."

Shikaki's center polls Palestinians on issues from politics to the economy to the peace process. He says there will be serious consequences for Abu Mazen and for Fatah, if the Palestinian Authority does not immediately begin to confront corruption, set standards of accountability, and institutionalize the judicial process. Fatah's credibility among Palestinians has plummeted since the second intifada began in 2000. According to many Palestinians, there are three reasons for this: the Palestinian Authority failed to give them a state, stole from public funds, and propitiated Israel. In contrast, Hamas was renowned for its integrity as well as its active resistance against Israel.

Abu Mazen won the presidency with 63 percent of the vote and a 46 percent turnout. Hamas won 70 percent of the municipal seats in Gaza with an 88 percent turnout. Shikaki acknowledged that Hamas did not do as well in the West Bank municipal elections as in Gaza and that abstentions in the national elections (in which Hamas did not run) do not connote the public's support of the Islamists. But he fears a snowballing effect. It is certain now that Hamas will run for the Palestinian Legislative Council. If Hamas is emboldened by the local elections -- and there is one major round left before the PLC elections in July -- then Shikaki estimates Hamas could take 40 to 50 percent of the PLC.

"Half of the chiefs of security are corrupt," Shikaki said, "and the public believes that 99 percent are corrupt. From now until May [when the next and largest round of municipal elections takes place], Fatah's main objective should be to address corruption."

Shikaki outlined four steps for Abu Mazen. First, he must appoint a new attorney general who is given a full mandate to act on corruption. Second, he must appoint a new chief of police who can be arrested for noncompliance. Third, he must allocate a budget to the courts and rebuild the prisons, because Israel destroyed every single prison in Palestine during the second intifada. Finally, the new minister of the interior and the minister of finance must begin submitting files of men to be prosecuted for corruption. The problem with this last step, as many Palestinians told me, is that many of the men who should be prosecuted are those closest to Abu Mazen: those who helped secure his election, his trusted advisors, the officials he relies upon for national security.

Though Abu Mazen needs a loyal security force to disarm the militants and maintain a cease-fire, a physical approach to confronting Palestine's militant factions (the Islamists, mainly Hamas and Islamic Jihad, and the Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigades, a militant offshoot of Fatah) will fail without a political approach. The Palestinian Authority must establish itself as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people. In the past, Hamas could easily present itself as an alternative to the P.A., because as Shikaki points out, the P.A. excluded Hamas from the political process by manipulating the electoral system.

"That's what we did in 1996," he said. "Hamas decided to pull out anyway, but even if they had run, they had no chance because we created a majority system that excluded everyone but Fatah." Today, 77 percent of the Legislative Council members are Fatah.

Shikaki continued, "When you follow a policy of exclusion, people take the battle out of the political system and into the streets." For this reason, he notes, Fatah was unwise to persuade Marwan Barghouti (the militant Fatah activist serving five life sentences in Israeli prison) to pull out of the presidential race. If Abu Mazen had run against Barghouti and won, it would have sent a clear message: Fatah chooses nonviolence. He did not run, so the issue of whether factions of Fatah still maintain violence as a viable tool remains unresolved.

Where Hamas is concerned, Abu Mazen will be unable to win back the hearts and minds of the people unless he moves the organization out of the streets and into the political arena. Hamas pulled out of the last Legislative Council elections in 1996 partly due to Fatah's efforts to exclude its opponents but mostly because Hamas refused to recognize the legitimacy of the Oslo process, which gave Palestinians some control over areas of the West Bank but ultimately failed to create a Palestinian state, stop Israeli settlement building, or even improve Palestinians' lives. It was Oslo's failure and four years of intifada that pushed the public mind toward Hamas, but Shikaki's public opinion polls show that 80 percent of Palestinians want a mutual cessation of violence. Seventy-one percent of the people who elected Hamas in the local elections are calling for an immediate return to negotiations. The public has grown tired, but so has Hamas. Israel assassinations and arrests have decimated their military leadership -- Shikaki says it is defunct in the West Bank. Finally, I have heard whispers from Palestinians and others that Hamas is eager for diplomatic relations with Israel and the United States. Suicide terror will bring them no legitimacy with either party.

Hamas has not definitively sworn off violence. Ala'a Rimawi, a West Bank Hamas activist, was clear on this point. "Hamas will stop the violence only if the Israelis cease their assassinations, dismantle the settlements, and make steps to leave the occupied territories. If not, the situation will return." But Rimawi was clear on another point as well: "It is the reality that Israelis have many parts of our land, so [Palestinians] cannot talk about the '48 lands [captured by Israel after its war of independence]. We can only talk about '67." It's no longer about what Hamas wants to do, Rimawi said, but what Hamas cando.

Neither of these opinions are new to Hamas' mainstream. Although the Western media seems not to realize this, or if it does, it fails to report it, a large gap has always existed between the ideals of their charter (which calls for an Islamic state in all of historic Palestine) and their practical intentions. A year and a half ago I spoke with Ghazi Hamad, editor of the Hamas-affiliated newspaper al-Risalah. The paper is based in Gaza, Hamas' stronghold and, according to Hamad, reflects mainstream Hamas opinion.

"For a long time we have accepted a state within the 1967 borders," Hamad explained. "But in our literature and in our education we say '48." The reason for this discrepancy, Hamad said, was Hamas' belief that Israel would never give Palestinians a state. Hamas would cease its call for the '48 lands only when Israel fulfilled the Palestinian right to statehood.

The occupation presents an ideological threat to the Palestinians as well as a physical one. Most believe, with reason, that Sharon has long desired to undermine the Palestinian national movement, to snub out their national identity and, therefore, their will to fight for statehood. It is in response to this, as much as to the checkpoints and tanks, that every Palestinian home has a map of historic Palestine with Al Quds (Arabic for Jerusalem), Yaffa and Nablus. Tel Aviv doesn't appear on a single one. Palestinians express their support for a state within 1967 borders even while sitting directly below such maps. Many also understand that after the creation of a Palestinian state, the majority of refugees expelled in 1948 and 1967 will be unable to return to their homes, now located within Israel; still, they entertain at least the hope of return. And as long as Israel categorically denies the principle of the refugees' right to return, Palestinians will continue to express this hope in the form of a definitive bottom line.

Abu Mazen has expressed a willingness to compromise on the right of return in the past. In 1999, he offered the U.S. a proposal for a final deal that required Israel to accept the principle of recognition, without demanding that all of the Palestinians in the diaspora be allowed to return to their homes. It is far too early to ask whether Palestinians would follow Abu Mazen down the road to such a deal concerning the refugees -- or any final-status solution. His concerns, such as the upcoming PLC elections, are more immediate.

Hamas' desire to run in these elections next month is a sign of the organization's growing pragmatism. According to Rimawi, many people within Hamas believe the Palestinian Authority is committed to accepting Hamas as a legitimate political partner. "The Palestinian Authority has a new vision of Hamas," he told me. "Not a small group but a significant partner."

I asked Rimawi what will happen to Hamas' policy of armed resistance -- something quite fundamental to the organization's identity -- once it enters the political realm.

"If you are in the government and you decide to have resistance, you will not manage to do it," Rimawi said. "Maybe you can have resistance, but then you can't have the government."

This point contradicted Rimawi's earlier statement that Hamas would reserve the right to violently oppose Israel. Could Palestine become like Northern Ireland, where Sinn Fein and the IRA operate simultaneously, or like Lebanon, where the militant Hezbollah is also represented in Parliament? Pollster Khalil Shikaki did not think so.

"I believe very strongly that when you incorporate Hamas into the political system, you moderate their views immediately," Shikaki said. "You saw this with the Muslim Brotherhood in Jordan and Egypt. Hezbollah has been able to have its cake and eat it too, but that's only because of Syrian and Iranian support. That's not the situation here, because the government wants to disarm Hamas."

Still, it is uncertain whether Abu Mazen has either the political will or the strength to do this. Palestinians close to Abu Mazen have suggested to me that he is prepared to draw Hamas in through diplomatic means but not confront them militarily. There are three reasons. First, he lacks legitimacy on the street. This is due to corruption within Fatah as well as Abu Mazen's political position. He does not have one clear constituency within Palestinian society, and he does not like to manipulate, so he will not play different factions against each other (as Arafat did) in order to maintain favor. Second, while he has a great deal of international legitimacy, he lacks international support. If the United States made a concerted effort to pressure Israel and back Abu Mazen, then Palestinians would back a military confrontation with Hamas. Finally, without U.S. support and an Israeli partner that believes in a equitable solution to the conflict (which even many Israeli observers agree Sharon does not), Abu Mazen's security forces have no impetus to take up arms against their Palestinian brothers. Palestinians do not share the West's distinctions between "good guys" and "bad guys." Even if Fatah and most moderate Palestinians do not agree with Hamas' tactics, they see Hamas as a legitimate organization fighting Israeli occupation, not as a cadre of terrorists.

A year ago I met with Mohammad Dahlan, Gaza's former security chief, and discussed his relationship with Hamas. Dahlan grew up with Hamas' leadership and attended university with them before the organization came into existence. Dahlan socializes with these men, drinks tea with them -- and throughout the Oslo years, it was his responsibility to arrest them and confiscate their weapons.

While men like Dahlan are not prepared to confront Hamas with violence (at least not without external support), they can reason with them. Abu Mazen has essentially told the militants: try it my way. Let's show the world that we are serious about instituting democracy, reforming the P.A., and curbing violence. Even if Israel undermines us in the short term, we'll secure international and U.S. support to pressure Israel to withdraw in the long term.

For the moment, Hamas seems to have agreed. At a summit in Cairo in mid-March, Hamas agreed to continue its hudna, or cease-fire, until the end of the year. In the interim, Palestinian factions would establish a "new PLO" that would include Hamas and Islamic Jihad. The new PLO would then assume responsibility for setting the Palestinian national agenda, including the possibility of negotiations with Israel.

But it is unclear how far the militants are willing to follow Abu Mazen before they tire of his diplomatic strategy. The success of the hudna depends on Israel's fulfilling its commitments: releasing prisoners, ending targeted assassinations and house demolitions, stopping closures, turning cities over to Palestinian control, and allowing no provocations or deviations from the road map. In that light, developments in Israel -- and Washington's response -- this week were extremely ominous.

The Sharon administration's plan to greatly expand Ma'ale Adumim, the West Bank's largest settlement, is the kind of unilateral action that could easily sabotage Abu Mazen's administration. The fact that the Bush administration, after initially criticizing the Israeli move, caved in and allowed Sharon to continue, was a severe blow to the Palestinian leader.

At the Cairo summit, settlement construction was classified as an "explosive issue" -- one that could lead to a renewal of violence against Israel. And this particular settlement construction could not be any more provocative. The 3,500 new homes would not only create a barrier between the West Bank and East Jerusalem, but would complete a circle of Jewish neighborhoods around East Jerusalem, in which the majority of the population is Arab. This encirclement undermines the possibility of one day establishing East Jerusalem, home to the third-holiest site in Islam, as the capital of a Palestinian state -- one of the crucial final-status issues, and probably nonnegotiable for the Palestinians and for the larger Arab world.

Though Israel maintains that physical changes to the landscape such as the security wall and even settlement construction (evidenced by the planned Gaza disengagement) are not necessarily permanent, Palestinians are extremely skeptical of such claims. And they know that these policies, aimed at creating "facts on the ground," only foment anger -- among the people as well as the extremists.

Yet Abu Mazen's ability to draw Hamas into the political system is another way of changing facts on the ground. As Shikaki says, once you integrate Hamas into politics, you quickly moderate them. Of course, he assured me, Hamas will never become Zionists. And though they have accepted the idea of a state within the '67 lines, they won't officially legitimize that decision. "But eventually the distinction between de jure and de facto will blur," he said.

Over the possibility of further Hamas violence, Jabril Rajoub was emphatic. "Fatah made a clear decision! Either we fight together or we negotiate together. On the ground we have one authority, one police, one institution. Hamas knows that in order to join the political process, they should accept the idea of a sole authority."

Perhaps the greatest hope for the Palestinians to navigate their way toward democracy and statehood lies in Abu Mazen's commitment to making clear decisions. You can't paddle in two directions at once, which is what Arafat had tried to do: simultaneously condemn and acquiesce to terror; appoint the arbiters of reform but imbue them with little authority; promise elections but withhold them indefinitely. Now, it seems Palestinians have grown tired not only of violence but also of this type of indecision. Of course, they will remember Arafat as a symbol of their struggle, the man who won them international recognition, but they will also see him as the man who failed to win a state for his people. In the reverence that surrounds it, as in its loneliness, Arafat's grave reflects both of these legacies.

"When Arafat died, every Palestinian felt something was lost," one young woman at the gravesite told me. "But Palestine isn't only him. It's a nation, and this nation needs to live."

Shares