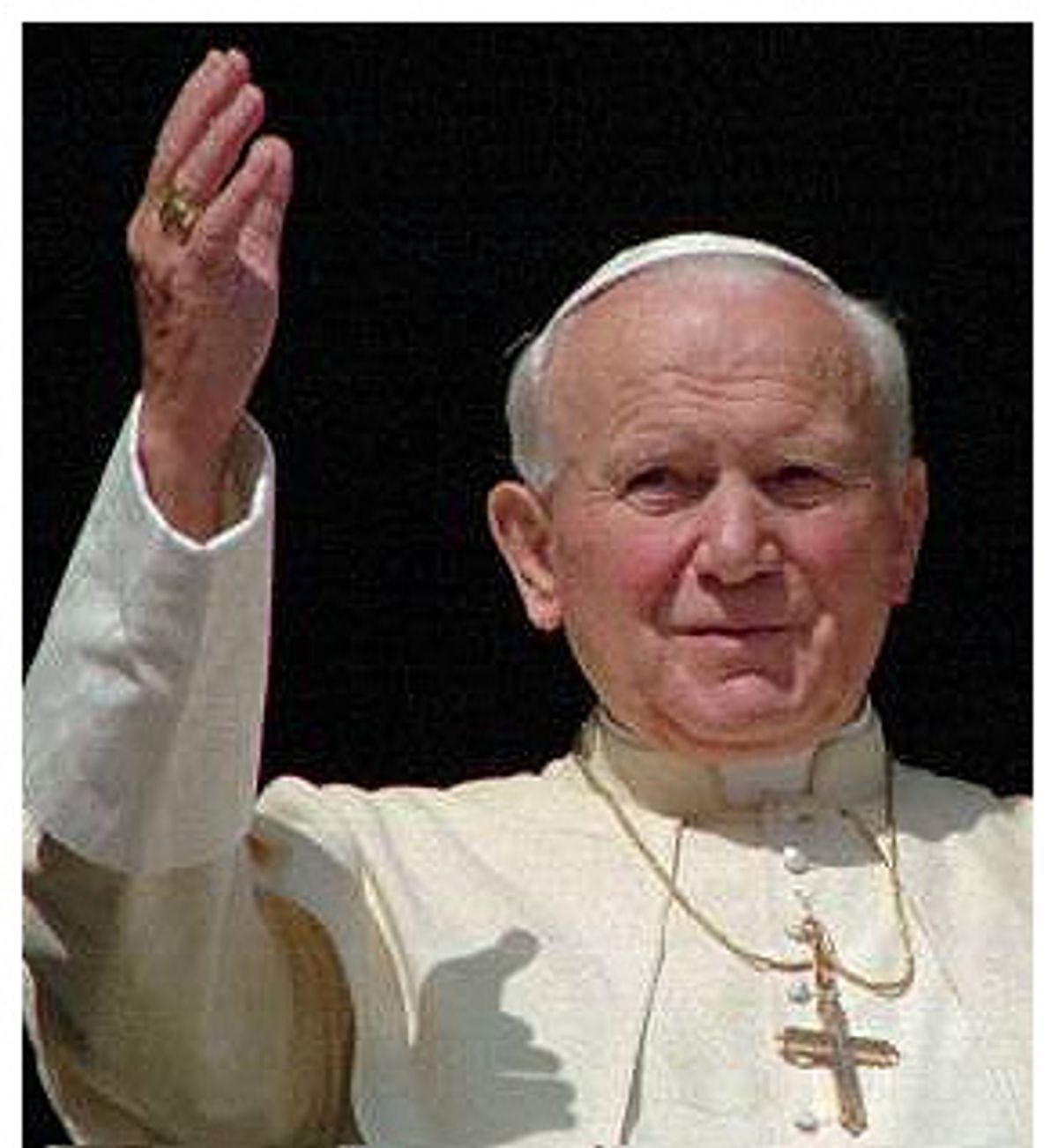

The pope is dead. Long live the pope. Although Pope John Paul II -- who began life in Krakow, Poland, as Karol Wojtyla -- died Saturday night at the Vatican, another man will soon be elected as his successor. Everyone knows that this is how it works, that the papacy is an office (albeit one invested with more spiritual authority and emotional resonance than the next), that it does end with the death of the man who fills the role. And yet such is the influence and impact of John Paul II that man and title have become nearly fused in one. We can no sooner imagine a new man filling his shoes than a new Elvis appointed as a replacement within weeks after Elvis Presley's death. It is unthinkable.

For millions of Catholics, John Paul II is simply the only pope they have ever known; his unusually long rule is the fourth-longest tenure among 265 popes over nearly 2,000 years. Throughout his 26 years as head of the Roman Catholic Church, John Paul II traveled to more countries than all previous popes combined. "He has changed the style of being pope," Father Thomas Reese, the editor of America magazine, told CNN. "It used to be that the pope stayed home in Europe."

In our contemporary celebrity-obsessed media culture, the pope was a ready-made star. The 1981 attempt on his life took place at the advent of cable news and was almost too good to be true for the nascent industry which, by the end of its saturation coverage, had turned the pope into an international star/almost martyr/hero. Even at the end of his life, the pope did not fade away quietly, hiding his decline behind curtains, but instead insisted on appearing to the public in his wheelchair, with breathing tube in place, as a symbol of suffering and in solidarity with the sick and frail around the world.

In practical terms, John Paul II has left a powerful mark on the Roman Catholic Church worldwide and the American church in particular, primarily through his teachings -- embodied most visibly in 14 encyclicals -- and appointments of Catholic leaders. During his papacy, he appointed the majority of bishops and cardinals currently serving in the United States. Long after his death, John Paul II's ideological positions and teachings will live on through the men he handpicked to lead the church.

Although American Catholics have constituted a significant portion of the population starting with immigration in the 19th century, it wasn't until the second part of the 20th century that the church really came into its own. The reforms of the Second Vatican Council -- primarily the work of Pope John XXIII -- played a large role in developing the modern American Catholic Church. But it was the leadership of John Paul II that shaped the Church post-Vatican II, setting the tone for Catholic engagement with the American public square and political life.

Many American Catholics believed -- and hoped -- that Vatican II would bring their church in closer alignment with modernity, perhaps even allowing more flexibility for the church to adapt to changing times. And it's possible that if another man had been elected to Peter's throne after the death of Pope John Paul I, the momentum of Vatican II might have swept more reforms through the Church.

John Paul II, however, while in some ways an unconventional selection -- the first non-Italian in more than 400 years, he spent part of his youth writing plays and had connections to the Polish Solidarity movement -- was theologically quite conservative. Under his stewardship, the church wavered little, even in the midst of turbulence. The Cold War came and went, sex scandals arose in the American church, and technological advances posed challenges to church doctrine. Through it all, John Paul II steered his church with an orthodox hand.

The pope's conservatism on issues of gender, reproduction and sexual orientation -- he staunchly opposed the ordination of women and took a hard line on homosexuality, abortion and birth control -- divided American Catholics. Yet the pope was not uniformly conservative in his thinking. Although the right wing embraced him, they were only able to do so by ignoring major aspects of his teachings. John Paul II's death, coming on the heels of Terri Schiavo's, is already prompting calls to honor his memory by embracing a "culture of life." But while the pope first introduced that phrase to our cultural lexicon, what he meant by it and what is meant by those who would claim his mantle are worlds apart.

You could be forgiven for thinking that "culture of life" was a concept created not by John Paul II but by George W. Bush. Few people have done have more to popularize the phrase -- if not its correct spirit -- than our current president, who used it even before his first presidential campaign in 2000. While the use of "culture of life" was almost always intended to communicate Bush's position on abortion, it was actually part of a larger strategy to reach out to Catholic voters.

The phrase was a central part of what is arguably John Paul II's best-known encyclical, Evangelium Vitae ("The Gospel of Life"), which he released in 1995. Bush's savvy Catholic advisors -- including conservatives Deal Hudson and Tim Goeglein -- knew that the phrase would immediately resonate with Catholic voters while indicating nothing more than vague pro-life sentiments to non-Catholics. Bush's communications staff did the same thing with Protestant hymns and phrases, using code words that went over the heads of those who didn't recognize them while resonating deeply with those who did.

During Bush's tenure, the phrase has been employed in the service of opposing abortion, stem-cell research, cloning and -- most recently and publicly -- the removal of Terri Schiavo's feeding tube. When, in the third presidential debate, Bob Schieffer asked the candidates a question about abortion, the first words out of Bush's mouth were: "I think it's important to promote a culture of life." A quick Internet search for the words "John Kerry and culture of life" and then "Tom DeLay and culture of life" revealed that the phrase is most often used by conservatives to attack Democrats who "flout the culture of life" and by liberals to sneer at Republicans and their "culture-of-life cronies." The culture of life has become cemented in American conventional wisdom as equaling conservative social issues.

But a fair look at John Paul II's use of the phrase and his political priorities must conclude that although he was undoubtedly concerned about abortion and stem-cell research and euthanasia, that list is far from complete. The pontiff also wrote about "the dignity and rights of those who work," and he spoke out against the widening gap between the world's rich and poor. He opposed both Gulf Wars in no uncertain terms and strongly communicated his outrage when the abuse at Abu Ghraib was revealed. During a 1999 visit to the United States, John Paul II spoke out against the death penalty, calling the punishment "cruel and unnecessary" and successfully petitioning for the commutation of a death sentence for a Missouri prisoner when he spoke in St. Louis.

Anti-death penalty, antiabortion, antiwar, anti-stem-cell, pro-worker, pro-poor, pro-sick. It's hard to think of any American politician whose positions reflect the entirety of John Paul II's "life" concerns. Even the American Catholic Church doesn't always reflect the pope's priorities. While John Paul II applied a fairly consistent ethic of life -- what the late Cardinal Joseph Bernadin called the "seamless garment of life" -- the National Conference of Catholic Bishops has taken a different stance. In 1998, the conference issued a letter called "Living the Gospel of Life: A Challenge to American Catholics" in which the bishops asserted that failure to following church teaching on abortion was more serious than any other issue, implying that a Catholic politician could neglect all other "life" issues and still be considered a good Catholic as long as he opposed abortion; at the same time, no amount of work for the poor or imprisoned or sick could save a pro-choice Catholic.

History will likely judge John Paul II as the pope of many firsts. He was the first pope to set foot in the nation of Israel, the first to enter a mosque and to visit a synagogue, the first to go to Greece since the Eastern Orthodox and Roman churches split over a thousand years ago. And he was the first to draw together centuries of Catholic teaching and vigorously promote them through the lens of "a culture of life."

His legacy, however, may be limited by an age-old reality: the tendency of political leaders and the faithful to hear what they want to hear and disregard the rest. "The culture of life" is not simply shorthand for abortion and gay marriage and Terri Schiavo. But those are the definitions that are well on their way to becoming the established understanding of the phrase. That would be an unfortunate, but not surprising, result of John Paul II's rule.

Shares