About halfway through Jane Fonda's new autobiography, she recounts a 1988 meeting with a group of furious Vietnam veterans trying to bar her from coming to Waterbury, Conn., to shoot the movie "Stanley & Iris." The group has burned Fonda in effigy, so she suggests a group-therapy session to heal the wounds. She writes that one of the angry vets told her afterward, "'You walked in, and I said to myself, Oh, she's so little. Just one little woman.'"

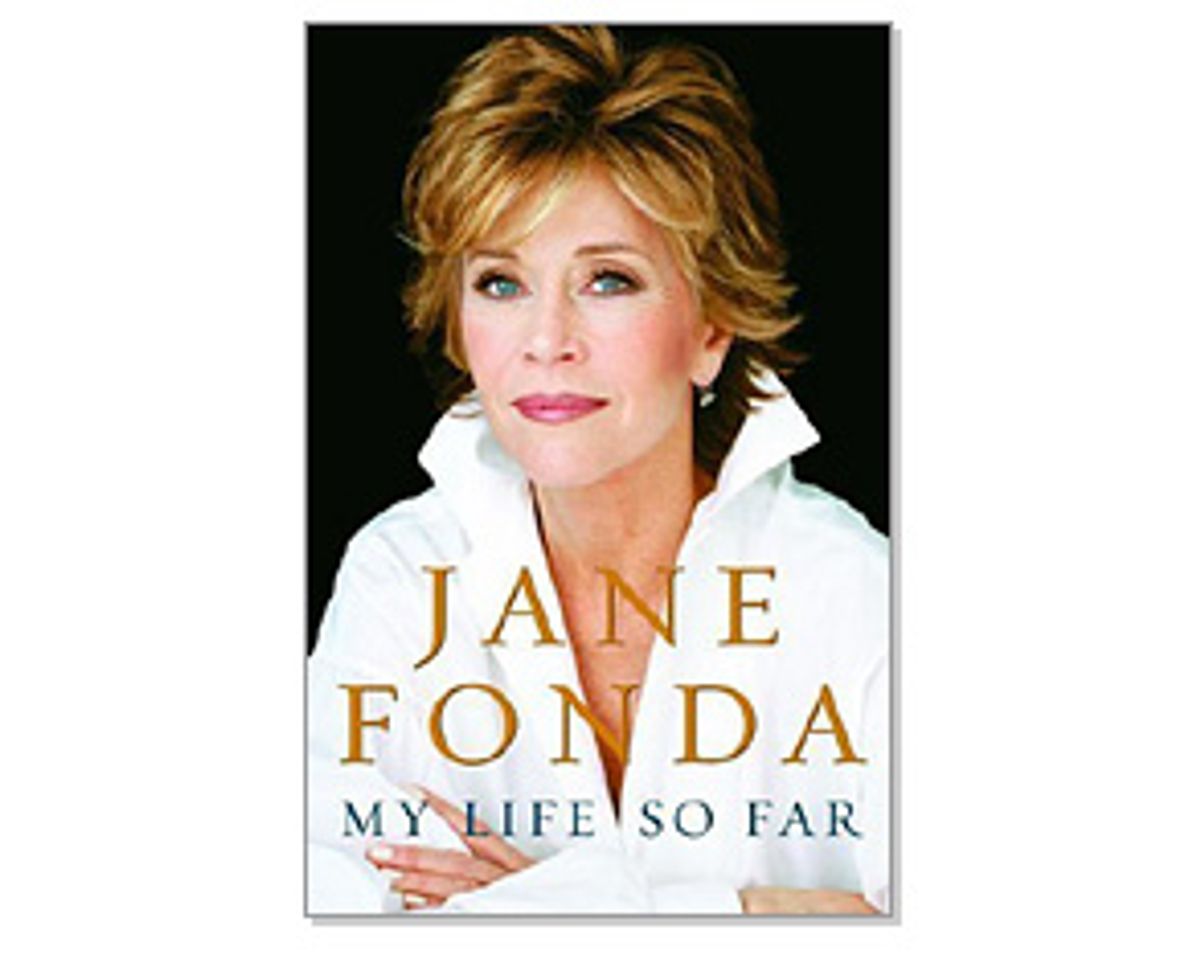

Jane Fonda may be one little woman, but she has written a big book. Her autobiography, uninspiringly titled "My Life So Far," chronicles her experiences as poor little rich girl in Hollywood, student at Vassar, space-age sex object in France, and activist in Southeast Asia. Involved in the feminist, civil rights and antiwar movements, Fonda has also won two Oscars. She revolutionized the exercise industry before marrying a mogul and giving up her professional life. She's suffered from bulimia, anorexia and a Dexedrine addiction. She has found God and runs a teen pregnancy-prevention program. Married to three wildly different men (French filmmaker Roger Vadim, politician Tom Hayden, CNN magnate Ted Turner), Fonda is biological mother to two children, adoptive mother and stepmother to a passel of others, including the daughter of a couple of Black Panthers. She has been an equestrian, learned to fly-fish, studied ballet, had fake breasts implanted and removed, and accumulated a hefty FBI file. It would not be a stretch to say that Jane Fonda has embodied a good deal of American women's history from 1937 to the present. Her 600-page autobiography -- which she wrote so that she could "own" her story, whatever that means -- is more personal revelation than cultural analysis, making it unclear how well Fonda understands the role she's played in history, or the way that history has played with her.

Fonda's series of timely transformations combined with her bumbling, slightly daffy attitude make her a Forrest Gump-ian figure. If something was happening in culture or politics, count on Fonda to have been nearby -- if not to have participated in it or created it herself. As the plane carrying her to Las Vegas for her 1965 wedding to Vadim rises out of Los Angeles, she happens to notice that Watts is on fire. While making "Barefoot in the Park" in 1967, her costar Robert Redford kvells about the little A-frame house he's just built in Utah. The house will become the Sundance Institute. In 1982, home-video magnate Stuart Karl suggests that Fonda turn her nascent exercise franchise -- founded to fund Hayden's political interests -- into a series of tapes. Fonda writes, "Home video? What's that? Like most people back then, I didn't own a VCR." "Jane Fonda's Workout" is, today, still the biggest-selling video of all time.

Fonda's book begins with disquieting recollections of her mother, a social butterfly named Frances Ford Seymour. By the time Jane (born "Lady Jayne Seymour Fonda") and her brother, Peter, are old enough to remember, Seymour has lapsed into periods of mental illness exacerbated by the fact that her husband, the actor Henry Fonda, has lost interest in their marriage. At 9, Fonda remembers watching her mother try desperately to get her father's attention by walking around naked. "She was probably still very beautiful, but -- oh, how I hate myself for this betrayal of her -- I saw her through my father's judgmental eyes," writes Fonda. "She wasn't doing the right things to make him love her. And what it said to me was that unless you were perfect and very careful, it was not safe to be a woman. Side with the man if you want to be a survivor." Fonda also recalls her disgust at seeing Seymour's mangled breast after an augmentation went awry. When Fonda is 11, her mother dies; Jane is told it was a heart attack. Soon after, she reads in a movie magazine that Seymour slit her own throat with a razor.

It's Fonda's guilt about her relationships with her parents that provides the foundation for much of her story: In trying to please her often-absent dad and not be like her mom, she winds up in three unfulfilling marriages to men as emotionally chilly as her father and repeats her mother's quest for physical perfection (including her own breast augmentation). She enters her father's profession, appearing in classics like "Klute," "The China Syndrome," "Barbarella," "Coming Home," "The Morning After" and "On Golden Pond." Having absorbed Henry's quiet, left-leaning politics, Fonda becomes a loud activist, and gets labeled "Hanoi Jane" after her 1972 trip to North Vietnam.

Fonda wrote her book on her own, without the help of a ghostwriter, and there are many places where it shows. Her chronology is often confusing: looping back and jumping forward, sometimes by decades. She doesn't seem to have much of a head for numbers, either; ages and dates don't always match up, and are often left out completely. Fonda's tone is conversational, and she dots many of her paragraphs with comic-book exclamations: "Wow!" "Weird!" "Ouch!" Her tenses jump from present to past so often that eventually they all blend together, and the text is riddled with emotionally emphatic italics, especially in chapters about politics -- "What are involved, informed citizens to do when presidents, vice-presidents, and secretaries of state give the public falsified evidence to justify war?" -- and her love life: "[Hayden was a] respected movement leader, passionate organizer, and strategist par excellence, who was even into American Indians." (Fonda has a thing for American Indians, and recalls praying to god, as a little girl, to make her brother, Peter, an Indian. She also likes men who are into bison. Seriously.) Fonda reports that "the Nixon Justice Department freaked" after the publication of the Pentagon Papers. At one point she disconcertingly asks readers: "Did you ever see the movie "Scent of a Woman" starring Al Pacino?" She is often "twitter-pated," experiences several "tectonic shifts" and sees many events as "germinal."

"My Life So Far" is also larded with the self-help-y assertions of a woman who has spent many years in therapy and a lot of time with Eve Ensler, as indeed Fonda has. There is a lot of talk about how she's been "disembodied" and needs to "own" her leadership, her voice, her sexuality, etc. Fonda apparently has never met a popular self-diagnosis she hasn't liked, so pages at a time are gunked up with Oprah-isms about "the disease to please" and Robin Morgan's "nictitating membrane" (the milky lid that cats have over their eyes) that Fonda writes "would settle over my being." To make use of Fonda's italics: What does that mean? The moments in which Fonda indulges in this sort of self-analysis are the weakest and dullest parts of the book.

But they are most frustrating because they distract from the deeply weird ride that Fonda takes us on. Her ability to absorb the ideas of those around her isn't always gag-inducing; it can also be pretty comical. Fonda claims to be a rapacious reader, and scatters quotations from other texts throughout her book. Of course she may have written her life story with a Bartlett's close at hand, but she deploys her references with an enthusiasm that suggests she has probably read most of the works she's drawing on. Among her favored sages are Rainer Maria Rilke, Carrie Fisher, Mary McCarthy, Florence Nightingale, Charlotte Brontë, Rumi, Philip Lopate, Carolyn Heilbrun, Quincy Jones, Thomas Edison, Katharine Graham, Joseph Campbell, Robert Heinlein and Howell Raines ("Fly Fishing Through the Midlife Crisis").

Fonda is not shy about showing readers how her consciousness has evolved, and how little she knew to begin with. She recalls how when her first husband, Roger Vadim, exclaimed in 1964 that America will never win a war in Vietnam, "I wanted to ask 'Where is Vietnam?' but I was too ashamed." A 1970 journal entry that Fonda reprints in the book reads: "Don't understand the women's liberation movement. There are more important things to have a movement for, it seems to me." "Did I write that? Whew!" is her present-day self-chastisement. Fonda scolds herself repeatedly throughout her autobiography. At times it feels as if every other sentence is about her anger at herself for having been so weak.

Her self-punishment makes a reader feel sad for this woman who is so much harder on herself than anyone else (except for a few thousand angry veterans) could ever be. There is something depressing -- if sort of charming -- about Fonda's aspirations to better herself. When she has a daughter, she names her Vanessa, partly in tribute to actress Vanessa Redgrave, whom she doesn't even know well at the time. But Fonda is fascinated by her because "she is strong and sure of herself and was the only actress I knew who was a political activist." True, Fonda admits, she "didn't know the particulars of her politics" back then. But she had once read in a magazine that Redgrave "went to bed studying Keynesian economic theory!"

Fonda's multiple and varied incarnations make for moments of vertiginous absurdity, especially during the 1960s when she is getting her consciousness raised while living in France with Vadim and making Hollywood movies. Al "Grandpa Munster" Lewis teaches her about the Black Panther Party on the set of "They Shoot Horses, Don't They?" And to satisfy her curiosity about what exactly is going on in Vietnam, she visits her mentor Simone Signoret, a leftist actress married to Yves Montand, at the couple's home outside of Paris. "Bringing a bottle of fine cabernet and a platter of cheeses, she took me out to the back porch, where we ensconced ourselves in an arbor," writes Fonda. Signoret fills Fonda in on the history of French colonialism, and how Ho Chi Minh petitioned Truman for help and was ignored. "She stopped to sip her wine," writes Fonda. "I took notes."

In the same vein is her awakening to the civil rights movement in America, which takes place while she is floating in an inflatable raft off the shores of St. Tropez, reading "The Autobiography of Malcolm X." "It rocked me to my core ..." she writes. "I began to search my soul to see which kind of white person I was. While theoretically I didn't think I was racist, I hadn't had enough contact with black people to know with certainty ... Malcolm had allowed me for the first time to have a glimpse into what racism feels like to a black man. What I was not ready to acknowledge was how the black women in his life were viewed as mostly irrelevant, voiceless, subservient." There you have it: major contradictions presented by the social movements of the mid-20th century, as considered by young Jane Fonda floating on her raft in St. Tropez.

Fonda's political thinking inevitably becomes more rigorous with age, and by the time she gets to the chapters about Vietnam and activism, she relies heavily on -- and footnotes -- documents like the Pentagon Papers and her own FBI files, which she has obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. At one point, she quotes transcripts of conversation between Nixon, H.R. Haldeman and Henry Kissinger as evidence that despite public denials by the government, the U.S. was bombing dikes in North Vietnam, leaving Vietnamese civilians vulnerable to drowning and starvation. This was ostensibly the reason she visited the country in 1972, enraging veterans by meeting with POWs, addressing troops on Radio Hanoi, and sitting on an anti-aircraft gun that had been used to shoot at American planes. It earned her the nickname Hanoi Jane, and her story about the trip will surely be the centerpiece of most of the press about her book.

Though her explanation of the trip is being billed as "an apology" for her actions, it's a vast overstatement. "I do not regret that I went," she writes. "My only regret about the trip was that I was photographed sitting in a North Vietnamese antiaircraft gun site." In the chapter, she claims that she was led by guides to the gun, and didn't realize how it looked until minutes after she stepped away, when she became horrified about how the image could be read. Now, she writes, "I realize that it is not just a U.S. citizen laughing and clapping on a Vietnamese antiaircraft gun: I am Henry Fonda's privileged daughter who appears to be thumbing my nose at the country that has provided me these privileges ... And I am a woman who is seen as Barbarella, a character existing on some subliminal level as an embodiment of men's fantasies: Barbarella has become their enemy ... I carry this heavy in my heart. I always will."

Gender ambivalence undergirds Fonda's entire narrative. It connects her childhood traumas, when she became obsessed with transsexual Christine Jorgensen because she herself wanted to be a boy, to her adult sexual relationships, in which she admits she gets subsumed in her male partners. She writes about women in politics, women in business, and women's health issues. During her marriage to Ted Turner, Fonda becomes interested in Christianity, but is concerned about her place in its patriarchal structure. There is a lot of Ensler-inspired writing about her vagina, and even a few pages in which she frets about the connections between gender inequity and overpopulation.

It's an impressive examination of how being a woman seeps into every corner of a personal, political, professional and physical life. But as fraught as she admits her relationship to her own womanhood is, there are complications that show up in the book that she doesn't even seem conscious of. At times it feels as though she gets as far as sex-positive therapy-heavy diagnoses but can move no further in her own analysis: She felt she had to be perfect, she sought out uncommunicative men, she needed to move her feminism from her head to her body. But there is a lot more going on in her story than she seems to understand.

Throughout, Fonda castigates herself for being the kind of woman who lives to please a man, starting with her willingness to place worms on a fish hook to impress her father while her brother is too grossed-out to do so. These impulses certainly play themselves out in her marriages. She allows Vadim to bring other women into their bed for threesomes she now claims to have hated. She stays with Hayden who, obviously threatened by her success, makes her feel insignificant and stupid. (Hayden comes off as the biggest loser in the bunch.) By the time she meets Turner, whose comically energetic desire for her can't mask the fact that he has no interest in what she has to say and that he insists she quit her jobs, it's tempting to shake a fist at Fonda and ask her why she can't just stand up to a man, already! It's not only a question for readers. Fonda reports that when she asks her grown daughter Vanessa to help make a movie about her life, Vanessa spits back, "Why don't you just get a chameleon and let it crawl across the screen?" Fonda admits that maybe she "simply become[s] whatever the man I'm with wants me to be: 'sex kitten,' 'controversial activist,' 'ladylike wife on the arm of corporate mogul.'"

But all the self-flagellation leaves something out: Fonda's obsession with women. Whatever she may say, Fonda simply cannot convince a reader that she prizes male over female every time. She may not have liked her mother much, but the rest of her story is full of respect and admiration -- both intellectual and physical -- for other women, and much of it sounds more authentic than her affection for men. As a teenager Fonda notices Greta Garbo's "healthy and athletic" body; she comments that friend Elisabeth Vaillard "was handsome in a Georgia O'Keeffe way," and describes her producing partner Paula Weinstein as "a tall brunette with sexy brown eyes." She is full of love for her onetime stepmother Susan Blanchard, for friend Brooke Hayward, for Signoret, and for Dot, her daughter's nanny. She mysteriously points out to Hayden that a baby sitter is sexy (he promptly initiates an affair). And hilariously, in the chapters about the unwanted threesomes with Vadim, Fonda writes: "I'll tell you what I did enjoy: the mornings after, when Vadim was gone and the woman and I would linger over our coffee and talk." Whether or not Fonda has lesbian impulses -- she denies the rumors that she and Vaillard were lovers -- her obvious desire to surround herself with beautiful, compelling women belies her claim that she played only to the guys. Fonda may have seen herself as a man-pleaser, but her story makes it clear that it was often other women who pleased her best.

The confusions about gender are nowhere clearer than in the book's chapter about the making of "On Golden Pond." Fonda was a producer and supporting actress in the film, which starred Katharine Hepburn and her father. "On Golden Pond" has always been read as a cathartic coming-together of Jane and Henry Fonda, since the fictional relationship between Chelsea and Norman Thayer so closely mirrored the frosty bond between the real-life daughter and father.

When shooting the pivotal scene in which Chelsea (Jane) tells Norman (Henry) she'd like them to be friends, Fonda makes her father's eyes well up by touching his arm unexpectedly. She describes it as a very moving moment. But when it's time for her close-up on the same scene, she finds herself unable to cry. Fonda spies Hepburn -- who comes across in this book as a whacked-out, crotchety Yoda figure -- in the bushes, clenched fists in the air, cheering her on. "Katharine Hepburn to Jane Fonda; mother to daughter," writes Fonda, "she literally gave me the scene."

Hepburn also goads Fonda into performing her own back-flip in the film, another of the major turning points in the fictional father-daughter relationship. Afraid of Hepburn's disapproval, Fonda forgoes a body double and spends all summer practicing the difficult dive herself. One day, she gets it. "As I crawled, battered and bruised, onto the shore, out of the nearby bushes appeared Ms. Hepburn. She must have been hiding there, watching me practice. She walked over to where I was standing and said in her shaky, nasal, God-is-a-New-Englander voice, 'Don't you feel good?'" Fonda acknowledges that the dynamic was skewed. "It was odd," she writes. "In the film the back-flip was to prove myself to my father. In real life I had proved myself to Ms. Hepburn. Dad probably couldn't have cared less if I'd done the dive myself or used a stunt double." Fonda may think she spent her life looking for her daddy's approval; scenes like this suggest that her dead mother may have left an even deeper scar.

Fonda's story, complete with its parenting "issues," its messy marriages and divorces, and of course its historical backdrop, is a peculiarly American document. Fonda spends a lot of time in her discussion of Vietnam insisting that she is a patriot, but her patriotism is perfectly evident throughout her life: in her obsession with her father's portrayals of Abraham Lincoln and Tom Joad and Clarence Darrow, in her examination of several presidential administrations, in her interest in social justice. But it's also clear in her unexpected fascination with the country's landscape. There are the lichen-covered stone walls of Connecticut and smoggy valleys of Southern California, sure. But what's surprising are Fonda's detours, like a too-good-to-be-true early-1980s bus trip she makes to the Ozark and Smoky mountains with her own personal spirit guide, Dolly Parton, in which she cooks and eats a possum. Fonda also writes rapturously of rowing through South Carolina swamps on an early-morning quail hunt with Turner. And then there's the chapter section she begins, "One day around the time I turned 59, I was participating in the annual bison round-up on one of Ted's New Mexico ranches."

There's an awful lot of personal terrain that Fonda only touches on in her book. Readers might have appreciated a clearer and more thorough discussion of her religious epiphanies, a longer look at what happened to her children and brother. Only a few sentences are spent on her own drug and alcohol use, and she declines to name several of the men with whom she had important affairs or go into detail on why her marriage to Turner ended. Of course, many memoirists could have woven individual books from each thread of Fonda's personal tapestry: Vietnam, eating disorders, growing up with a famous father, marriage to famous men, exercise dynasty ...

Fonda somehow mashes it all into one book. Does she contradict herself? Sure she does. She contains multitudes.

Shares