My mother stopped going to church a few months before she died. It was an odd time for a lifelong Catholic with terminal breast cancer to forgo the solace of Mass, but one day it wasn't solace anymore. She came home on a Sunday in early 1976 in tears. Looking for spiritual comfort, time with God, transcendence as she approached death, she'd instead been subjected to a sermon that was a fiery antiabortion harangue, in which the priest proclaimed that pro-choice Catholics weren't Catholic at all and were going straight to hell.

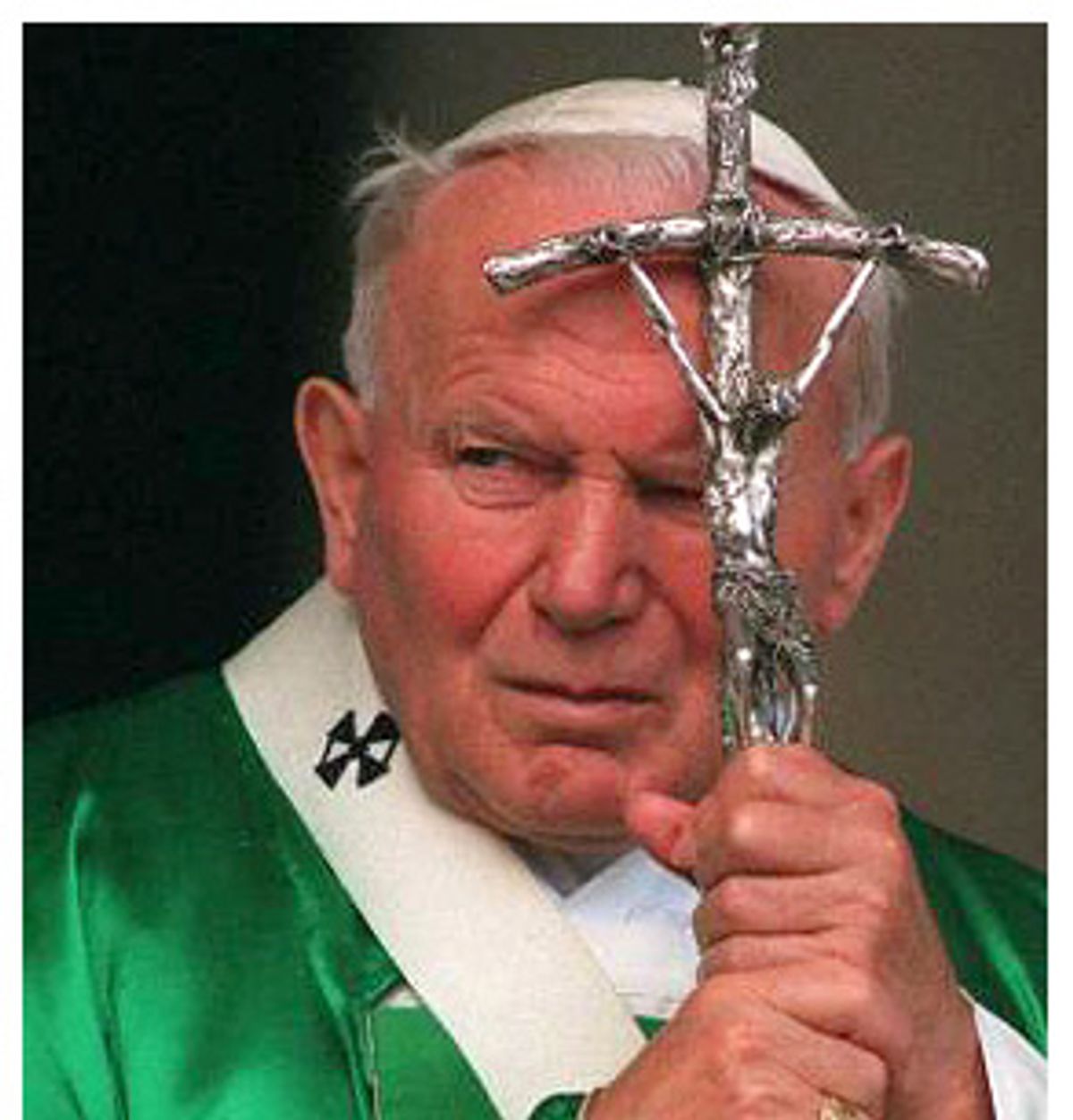

The sermon enraged my mother, even though I don't think she considered herself a pro-choice Catholic. I'm a little ashamed that I don't know for sure, but sometime in the early 1970s we stopped talking politics. I knew she was the house conservative, since my father's politics were well to her left. Still, she was appalled by the church's turn to blatant political campaigning on culture-war issues, especially abortion, at the expense of dispensing spiritual wisdom and comfort. I've thought about my mother all weekend as I found myself unable to mourn Pope John Paul II. Although he didn't reach the Vatican until two years after she died, when he got there he promoted leaders just like the antiabortion zealot who so wounded my mother. He cracked down on all dissent and toughened the church's teachings on issues of sexuality -- which happen to be issues of love -- which even my somewhat conservative Catholic mother was wise enough to know might require different answers for different hearts.

My mother and much of her family were proto-Reagan Democrats, pre-Ronald Reagan working-class Catholic ethnics who began to fear their party in the wake of what the movements of the 1960s unleashed. But my mom didn't start out that way. Early on she was warmed by the sunny breezes of curiosity, activism and hope heralded by the civil rights movement and feminism, but most of all by Vatican II. Pope John XXIII was a hero in my household (along with John F. Kennedy), and the two leaders' convergence seemed to usher in a new era of engagement for American Catholics. The English Mass, new roles for laypeople and women, the emphasis on a direct relationship with God, the overall opening up to questions and new thinking -- it seemed epochal, linked to a worldwide spiritual and political enlightenment. For many people the '60s died in 1968 with the murders of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy, but for liberal Catholics the year things went bad was 1963, when John Kennedy and Pope John XXIII died. My parents mourned both deeply.

Still, they took the promise of Vatican II seriously. They began going to ecumenical Seders at the local Temple Avodah, taking us to the morning Folk Mass, encouraging our spiritual questions. President of our Parish Council, my father defended my substitute teacher, who was nearly run out of town for holding an impromptu sex ed talk with eighth graders (we totally set him up) in which he mentioned condoms. I knew all about condoms; I'd found them in my father's sock drawer a few years earlier when I was putting away his laundry. I knew my parents loved the church but looked away from some of its harsher, anachronistic teachings -- three children were enough! -- and they were teaching my brother and sister and me to do the same.

But at some point the church began to fight that kind of relativism. And my mother was susceptible to the message, in national politics too, that the change had all been too much too soon. She was frightened by the tumult of the late 1960s and early '70s, where my father, who had studied to become a Christian Brother, opposed the excesses but embraced the rest of it. For the first time political argument shook my home, where consensus -- about the Kennedys, about the civil rights movement, about the Vietnam War -- once reigned. The worst was when my mother, reminding us that we enjoy a secret ballot in the United States, thank you very much, wouldn't tell us who she supported for president in 1972. We couldn't imagine that meant anything except that she'd cast a vote for Richard Nixon, and she died without telling us otherwise. It was a low point in my parents' loving partnership, but they mostly handled it with humor.

And yet, even as my mother began to count herself among the silent majority, to question the violence of the civil rights and antiwar movements, if not their goals, to embrace a certain authoritarianism in American politics and the church, she couldn't go all the way. Some of her resistance, I think, was the influence of feminism. She wanted a larger role for women in the church. She started using her maiden name, Webster, as her middle name and began to think about going back to work. And then her cancer recurred.

We didn't talk politics a lot in her last year, and yet I saw her shift back, a little, toward an acceptance of questions and uncertainty and rebellion. Dying I think does that. And while she was too much a traditionalist to completely accept abortion, from our conversations of the time I know she found the issue complex and painful. She was also too much a realist -- and, ironically, too much a feeling, compassionate Catholic -- to insist that there might never be a reason, a need, a crisis that caused a woman to make a different choice from one she herself thought was right. Dying and leaving behind three school-aged children certainly does that.

I don't completely know why my mother snapped on that Sunday when she heard the antiabortion sermon. Maybe she worried the priest was right, and even if she went to heaven she wouldn't see her pro-choice husband and daughter there. I just know that she was crushed, for that afternoon anyway. But I should note that my mother didn't die without the church. She'd befriended enough priests over the years that they came and said Mass at her bedside, gave her communion, provided her the last sacrament, the anointing of the sick. And they didn't trouble her with talk about abortion.

So I've watched the long goodbye to John Paul II a little aghast at the uniform tone of celebration, as though this pope had not presided over the shutting down of hope for so many Catholics with his 26-year reign. I applaud his commitment to youth, to the poor, to the Third World; his support for a Palestinian state and his opposition to the Iraq war. But I abhor what he did to the church itself. The priesthood is shrinking, thanks at least in part to the prohibition against marriage and against ordaining women. The sex-abuse scandal, which he did far too little to address -- and refused to directly apologize for -- drove more people away. And he enshrined a leadership cadre of close-minded zealots. We could next have a Nigerian pope, which would have thrilled both my parents, but like most of the cardinals appointed by John Paul II, Francis Arinze is a strident traditionalist who weighed in during last year's presidential campaign with the news that a pro-choice Catholic politician "is not fit" to take communion. I wonder if Arinze would have delivered it to my dying mother's bedside, given her doubts about the church's crusade against pro-choice Catholics.

This is not my mother's church, and it certainly isn't mine. I say that with a great sense of loss and sadness. Watching the pope's long death, I envied him the peace his faith gave him when he needed it most. I found it hard not to resent the fact that men like him denied it to my mother when she most needed it, choosing instead to harangue her about abortion. But she found the church she needed in the end. I don't expect to be so lucky.

Shares