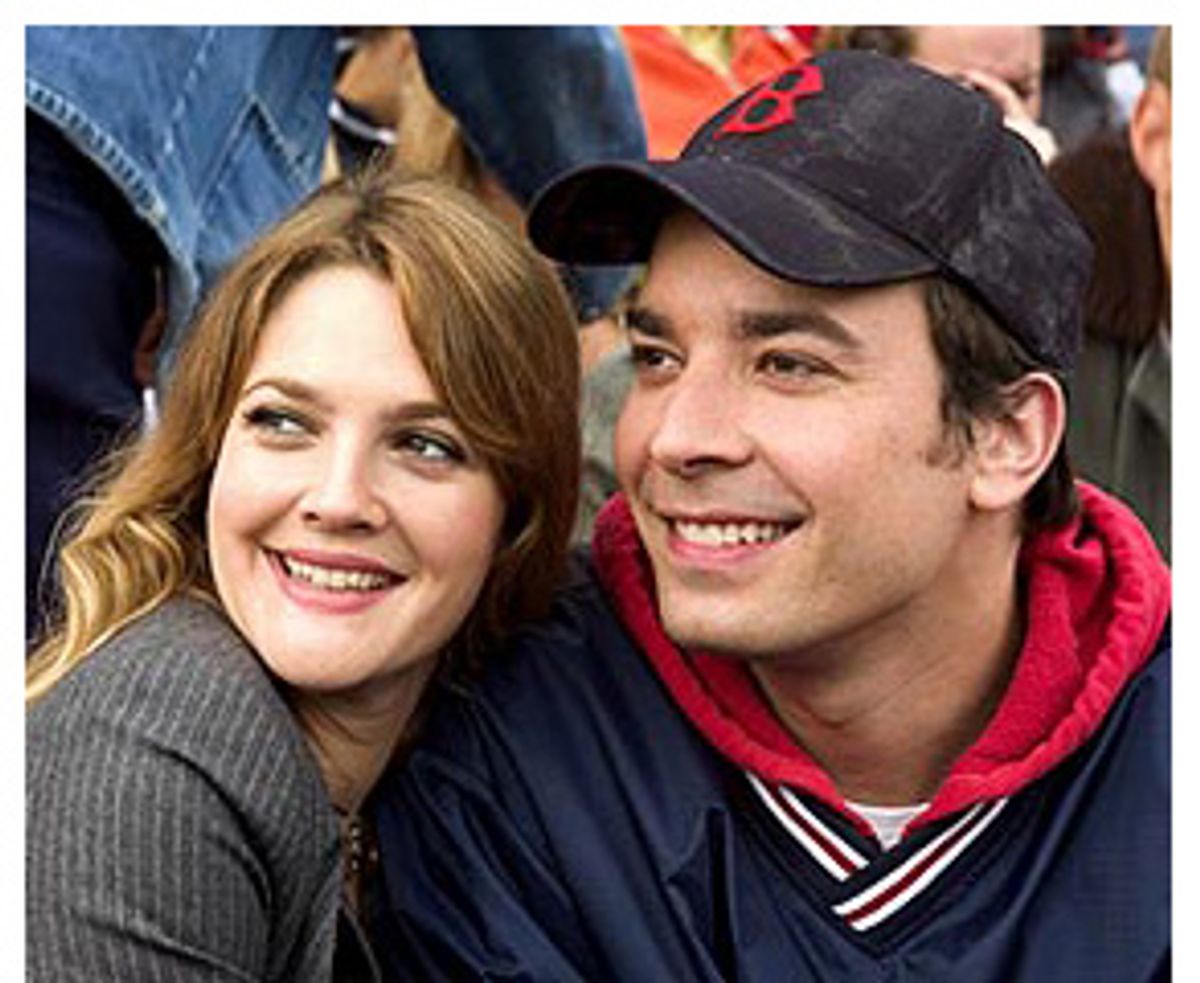

The end of an 86-year losing streak is a great backdrop for a romantic comedy, the perfect metaphor for finding love against all odds. In the Farrelly brothers' "Fever Pitch," Drew Barrymore and Jimmy Fallon find true love, just barely, as the long-beleaguered Boston Red Sox wend their way toward winning the World Series. The picture is supposedly about a character who puts his love of baseball before his love of actual people. But in some ways, the picture itself does the same thing. By the end of it, we have a vivid understanding of how desperately Red Sox fans care about their team. But the human-to-human love story tucked in amid the dementia feels like an afterthought, a workaround to the problem of being consumed by the love that, in New York City, at least, dare not speak its name.

Like nearly every Farrelly brothers movie that has come before it, "Fever Pitch" is made with so much genuine affection, and such obvious good intentions, that it seems churlish to treat it too harshly -- the picture is reasonably entertaining and shows glimmers of the Farrellys' characteristic offhanded sweetness. Yet my disappointment in it makes me feel I've been banished from Eden. "Fever Pitch" lacks that Farrelly spark, that warm, crazy glint that made movies like "Stuck on You" and the unfairly maligned "Shallow Hal" glisten, even through their flaws. That may be partly because the Farrellys didn't write "Fever Pitch": The script, inspired by Nick Hornby's 1992 memoir, is by Lowell Ganz and Babaloo Mandel, who specialize in sleek products like "Splash," "A League of Their Own" and "City Slickers." "Fever Pitch" may at times look and feel like a Farrelly brothers movie. But get too close and you see all the ways in which it just doesn't move as it should. It's an impostor in the correct uniform.

Fallon plays Ben, a 10th-grade math teacher whose shirttails are always dangling beguilingly over the waistband of his ill-fitting corduroys -- in other words, he's the kind of shy, smart, schlumpy charmer that, in the movie universe at least, women need to be convinced to look twice at, even though underneath it all he's supposedly the best kind of catch a woman could hope for. Luckily, successful, adorable career-gal Lindsey (Barrymore) does look twice, even though at first she's convinced Ben isn't her type. But their relationship gels immediately: On the night of what's supposed to be their first date, Ben tends to Lindsey (and cleans up) when a nasty stomach bug lays her low. Her dog adores him. The three of them have picnics in the park, during which Ben lists the things he loves about her -- you know, those inventories of stray freckles and unconscious instances of nose-crinkling that movie characters so often feel compelled to make.

But that's during the winter. What Lindsey doesn't know is that once baseball season starts, Ben belongs to the Red Sox. He has season tickets, and the seats are amazing: He inherited them from his uncle (played in an all-too-brief cameo by Boston comic Lenny Clark), who ignited Ben's adoration of the game when he was just a lonely, awkward kid. His friends (among them the always likable Willie Garson, from "Sex and the City") clamor for the opportunity to be his guest at select games.

Lindsey, at first, is happy enough to tag along with him, despite the fact that the "regulars" in the nearby seats clearly distrust her for not liking the game enough (or maybe for just not being working-class enough -- a bit of reverse classism that you wouldn't expect from the Farrellys, who are among the few filmmakers I can think of who actually get class). But before long, Lindsey realizes that the Red Sox schedule rules Ben's life. No family event is ever more important. He owns almost no grown-up clothes, other than sneakers and T-shirts. Tensions arise. She loves him, but what should she do?

All of that makes "Fever Pitch" sound disarmingly mild. You're probably wondering, "What's the girl's problem? He's a great guy, and he loves baseball -- so what?" And that is, ultimately, exactly what the movie wants you to feel, even though Ben's harmless love of baseball causes him to do some not very cool things. The Farrellys, New Englanders by birth, love the Red Sox so much that they forgive their lead character a multitude of sins that, in any of their other movies, they'd be too gentlemanly (and too humane) to ever allow. When Lindsey excitedly announces that she has to go on a last-minute business trip to Paris and is going to whisk him off for a romantic weekend there, he hems and haws -- he'll have to miss an important game. Understandably, she's stung. Meanwhile, we're left with one crisp image ringing through our brains: A weekend in bed, in Paris, with Drew Barrymore. What kind of schmuck would pass that up to watch a bunch of guys running around in tight pants?

Ben finally does allow himself to miss a game, only to ruin an exceedingly romantic moment -- the sort of moment at which both men and women are at their most vulnerable -- by grousing about not being at Fenway. And worst of all, when Lindsey is struck and knocked out by a foul ball while Ben's back is turned, he's more interested in high-fiving the guy who caught it; only after that does he notice his girlfriend, slumped unconscious in her seat. Later he watches this horrifying moment played out on TV, and while he flinches momentarily, the incident ends up meaning nothing to him. As Ben is written, he's the kind of great "catch" women would probably be better off not looking twice at. He's one of those ostensibly nice guys who's really not so nice at all.

Of course, by the end of "Fever Pitch," Ben has supposedly changed. But we don't believe it for a minute. Fallon is extremely well-cast as Ben -- in his early scenes, especially, his stammering awkwardness makes him at least vaguely appealing. But by the movie's end, we're long past the point of just wishing he'd grow up -- we've begun to suspect that his lost-puppy routine is just a coverup for an essential lack of character. And Barrymore, as always, is luminous and delightful, but the role is beneath her. (She needs to stop taking these cheerful girlfriend roles, especially in movies that she's involved in producing, like this one.)

"Fever Pitch" is really a love story about baseball, and considering the sport is our national pastime, there's nothing wrong with that. In Hornby's book, the game in question was football (that is to say, soccer), so for an American movie the switch to baseball makes sense: The perceived reality, at least, is that baseball fans -- particularly those persistently dreamy Red Sox types -- are much more delightfully innocent than those scary Anglo and European football fans. How many times have you seen the words "baseball" and "hooligan" used together?

But the reality is that, maybe particularly in Boston, baseball attracts its fair share of boozy loudmouths, as I can attest after having lived near Fenway Park for four years in the '80s. During baseball season, just getting home from the subway after work (dressed in ordinary work apparel, not expensive yuppie togs) meant trudging through bands of noisy cretins whose "love of the game" apparently translated into a special license to harass anyone not kitted out in a backward baseball cap. I would see parents, particularly dads, headed out to the ballgame with their kids, and feel bummed out that they had to reckon with these yobbos just to enjoy an evening at the ballpark. And I could never get over the fact that although Boston is an incredibly racially diverse city, the faces I saw coming to and from those ballgames were almost universally white.

That's not to knock baseball, a sport many people love for all the right reasons. (And the charms of Fenway Park, even to people who aren't baseball fans, are undeniable.) But to use romanticism of the sport as a substitute for actually writing a character -- "He's not a bad guy, he's just a crazy dreamer!" -- is lazy and dull. And while boyishness is charming, outright immaturity masquerading as boyishness wears thin pretty quickly. At one point in "Fever Pitch," Lindsey throws open Ben's closet door and, facing a sea of Red Sox jerseys, jackets and sweats, laments, "This isn't a man's closet!" It isn't a man's life either.

Shares