The 265th pope is being announced, and Al Franken is watching it live on CNN. The Air America radio host has his back to the microphone, as he sits in a blue sports coat, jeans and white Nikes, staring at the television across the dimly lit studio. On the line is Franken's one-time "Saturday Night Live" comrade Father Guido Sarducci. The fictional Father Sarducci is supposedly live from Rome. But the comedian who plays him, Don Novello, the Vatican correspondent for "The Al Franken Show," is calling from San Francisco. (The Swiss Guard once arrested Novello for impersonating a priest in Vatican City.)

Then the news breaks: German conservative Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger is the next pope. "It's an inside job," Sarducci moans. "You won't see the pope involved in local politics in Poland, no more, it's going to be Germany. You are going to see the wall go back up." Franken is cracking up.

But the normally outspoken comedian won't comment about the new pope. "As a Jew," he explains later, "it's none of my business." It's a rare reticent moment for Franken. His job is to make everything his business. The restraint seems oddly decorous for the man who once, to his face, accused Fox News star Bill O'Reilly of lying about his credentials at a Book Expo, leading an infuriated O'Reilly to scream, "Shut up, shut up!"

But Franken is tiring of merely being a provocateur. Although in just a year his show captured 53 stations nationwide, including eight of the top 10 markets, the most recognizable face of Air America Radio is becoming restless, and ready for a new challenge.

Al Franken wants to be a senator.

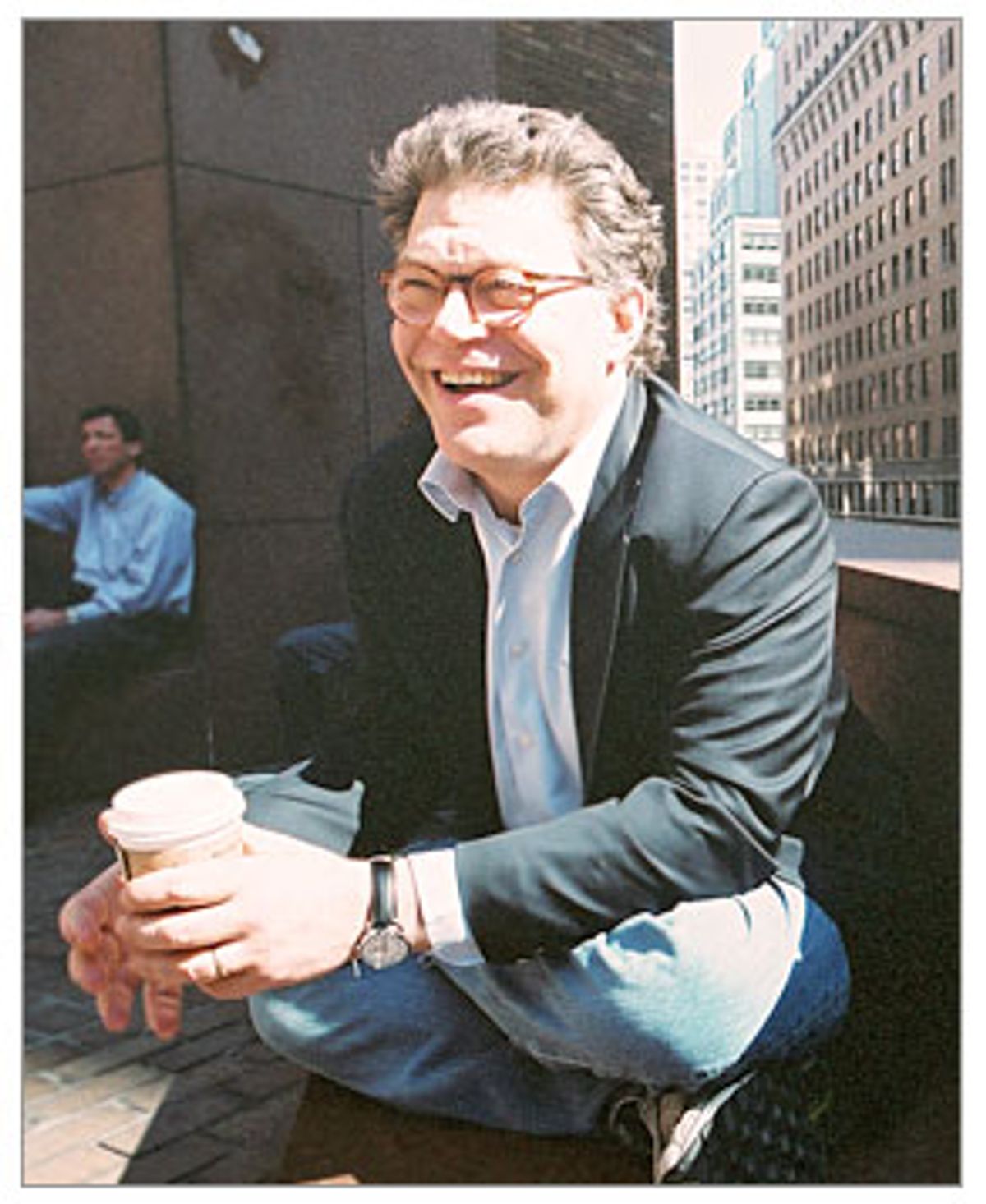

"I'd rather be part of [the process] than commenting on it," he insists. But he pauses, shrugs indecisively, a boyish chuckle follows. "I think. I don't know. That might be part of the calculus of whether I go for it or not." Whether Franken will "go for it" in 2008, against freshman Republican Sen. Norm Coleman, remains to be seen. "I can tell you honestly, I don't know if I'm going to run," Franken continues, as we now sit 41 floors below his studio, in the skyscraper's courtyard. "But I'm doing the stuff I need to do, in order to do it."

That stuff includes moving home to Minnesota after three decades away. He's buying an apartment in Minneapolis, and moving his radio show to the Twin Cities. He's talking about political action committees and fundraising with key state and national Democrats, looking to raise money for candidates in the 2006 elections. After years of stumping for Democrats nationwide, he has some chits to cash in. "He has national reach; his name and who he is will attract small contributors and large contributors from all over the country, so a lot of little folks too," says Democratic strategist Joe Trippi, who managed Howard Dean's 2004 presidential campaign. "In that way he's like the Dean campaign because he's really somebody that can energize not just Minnesota but around the country, to get involved and contribute."

For a man who exudes New York, who is an icon of the mythologized early days of "Saturday Night Live," who sips a latte now in half-lotus position (Franken happens to be an unusually flexible man), Minnesota may seem a world away. Then you meet Franken. You see he always wears sneakers. You notice he speaks too slowly to be a New York native. You listen as he talks about his Minnesota childhood from his first days in kindergarten, in a small town on the southern border, to his last days of high school in a middle-class suburb outside Minneapolis. And you finally realize: Like so many Midwesterners-turned-New Yorkers, Franken is an expatriate, in love with two lands.

"I feel comfortable in both places," the 53-year-old says, taking off his sports coat and setting it beside him. It's the first day in New York that feels like summer, over 70 degrees, the kind of day that makes adults consider playing hooky. "Remember, my parents stayed in Minnesota, so I went back all the time and I have certain friends that I see all the time that are really good friends, and I do feel like a Minnesotan. I am a Minnesotan and not just because I root for the Vikings and the Twins," he continues. "I like the Minnesota-nice sensibility. I like the liberal tradition; I like the Hubert Humphrey tradition fighting for civil rights."

But that's the Minnesota of Franken's youth. The purple Vikings now represent a purple state. Today, Minnesota has exactly as many Republicans as Democrats. Despite that, Franken feels ready to run. "Twenty years ago, I wouldn't have thought about it," he says. "But I've been thinking about it long enough that it doesn't seem so strange." Then he quietly chuckles.

He does that a lot. Franken cannot tell a joke without making himself laugh, but it's not a guffaw, a belly laugh or a giggle. It's a chuckle. He might do it a hundred times a show. But his candidacy, Franken insists, is no joke. The comedian might come off perpetually cheerful. His constantly crooked glasses, chubby face and dimples make him seem boyishly chipper. But Franken is serious when he cares about something. He wrestled in high school. During the 2004 New Hampshire primary, he pinned a man heckling Howard Dean. And in 2003, Franken upbraided Bill O'Reilly at a book fair, flustering the conservative commentator. (Neither O'Reilly nor Rush Limbaugh would comment for this article.)

"I do take politics very seriously even though I'm a comedian. I never thought there was a contradiction in it; I always thought that comedy and satire are a legitimate way of dealing with very serious things," Franken continues. "Having a sense of humor helps. If you look at terrorists, they really have no sense of humor." But then he changes gears, a little. "Minnesotans take their politics seriously and running for Senate is a big deal."

It's certainly a big deal for the Minnesota Democratic Party. "Franken's viable, no question," says Minnesota Democratic strategist Wy Spano, who is also the director of the Center for Advocacy and Political Leadership at the University of Minnesota at Duluth. "There's lots of buzz about him. I really do think that Al Franken as a star will bring lots of folks, and lots of money to the party."

Publicly, at least, Minnesota Republicans say they're looking forward to running against Al Franken, star of television and radio, darling of the Hollywood left. "I would love to see Al Franken in rural Minnesota standing in the cornfields with farmers and talking to them about farming and agriculture prices when he's spent the last 20 years in New York City in a very elite, sort of liberal environment," Minnesota's Republican Party chairman, Ron Eibensteiner, says. "Minnesotans experimented with a comedian-type unprofessional public servant with Jesse Ventura, and it didn't work out very well."

Former Gov. Ventura is no Franken fan, either. "People love to compare themselves to what I did. They did it with Schwarzenegger in California. He's just another Republican," says Ventura, who in 1998 stunned the Minnesota political establishment by winning the state governorship as a Reform Party candidate, with a mix of brazen speak and grass-roots realpolitik. "You have to remember something -- I took on two endorsed candidates of the Democratic and Republican powerhouses, Humphrey and Coleman, and defeated them. Al Franken would be just another Democrat."

Ventura makes a couple of good points: Unlike Ventura, Franken doesn't currently live in Minnesota, and he hasn't held elected office. (Ventura was the mayor of Minnesota's sixth largest city.) And Norm Coleman, Ventura notes, is no pushover. "Coleman is savvy. He's spun well. He's in very tight with President Bush," Ventura says. "The moment [Franken] declares his candidacy, he has to go off the radio. He has to look forward to having his entire past exposed. He'd better come clean and be honest with it. If he's done drugs in the past, he better be honest about that. He better be honest about things he did at Harvard, if he has anything in the closet," because, Ventura emphasizes, Coleman is "going to have the Republican machine behind him 110 percent."

Coleman wasn't always the darling of the right. He used to be a Democrat, but after one term as the mayor of St. Paul, Coleman switched parties in 1997. "The cities, St. Paul and Minneapolis, are as Democratic as you are going to get," University of Minnesota political scientist Lawrence Jacobs explains. "I mean San Francisco Democratic." But Coleman still won reelection in 1997, becoming the first Republican mayor of St. Paul since 1960. In 1998, he lost the gubernatorial race to Ventura by three percentage points. But a year later, he picked up an important ally: George W. Bush. He went from serving as the state party chair of Bill Clinton's candidacy in 1996 to heading George W. Bush's Minnesota campaign in 2000. It was President Bush who asked Coleman to run for Senate in 2002. Vice President Dick Cheney then pressured Coleman's Republican opponent to step aside. Coleman coasted through the primary, only to face liberal icon Paul Wellstone.

Despite the high-level GOP support, he was trailing Wellstone until the progressive icon died in a plane crash 11 days before the election. With the Democratic Party in turmoil, former Vice President and two-term Minnesota Sen. Walter Mondale was asked to step in. Quickly, Mondale took the lead. And just as quickly, the political momentum shifted, especially after a raucous Wellstone memorial service (Sen. Trent Lott and other Republicans who attended were booed) was depicted by conservatives in the media as an example of Democratic excess and dysfunction not seen since the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago.

To Franken, who attended the funeral and memorial service, it was Coleman who capitalized on the death of Wellstone, and the media firestorm that followed. It is this same political opportunism, Franken says, that motivated Coleman to call for United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan to step down at the close of 2004. Coleman made national headlines by stating that Annan was ultimately responsible for corruption in the Oil for Food Program. "It was grandstanding," Franken says. "I mean, there was no evidence of any wrongdoing; the secretary general didn't administer the program. It was mainly administered by the Security Council, the United States and Great Britain. So I thought it was a cynical indictment of a man trying to get on TV." After repeated efforts, Coleman declined to comment for this story.

Even some nonpartisan observers insist Franken will have a hard time unseating Coleman. "Al Franken is a comedian," Jacobs says. "He hasn't lived in the state for a number of years. Why do we take it seriously apart from the fact that this guy creates a scene?" Jacobs doubts that Minnesotans are ready to send a comic to the Senate, where despite the vitriol of modern politics -- even as the "nuclear option" looms -- senators refer to bitter partisan foes as "gentlewoman," "good friend," "distinguished." "You have to be very cautious as a candidate in what you say and how you say it," Jacobs points out. "Where's the record of Al Franken doing that? The one-liners don't work in politics; they really turn people off."

You could see both the promise and the risk of Franken's comic background when he did his friend Garrison Keillor's "Prairie Home Companion" one Saturday night early in April. Keillor is one of those who originally asked Franken to consider entering politics. At the New York studio broadcast, Franken did a long, moving monologue about his working-class dad. "My dad loved comedians, especially George Jessel, and he loved Henny Youngman and Buddy Hackett," Franken says. "We're Jewish, OK?" The crowd is cracking up.

Later in Franken's life, he met Hackett. And to the audience he explains: "The first thing he did was tell me a joke and it's my favorite joke, so I'm just going to tell it. This is it, Buddy Hackett joke: A guy goes into a doctor's office; he's got a dot on his forehead. The doctor says, 'Oh my God, I've never seen it before but I read about it in medical school.' The guy says, 'Well, doctor, what is it?' 'Well, in six weeks you are going to have a penis growing out of your forehead.' The guy says, 'Well, doc, cut it off.' [The doctor replies] 'I can't cut it off; it's attached to your brain, you'd die.' So the guy says: 'So, doctor, what you're telling me, is that in six weeks, every morning when I wake up and look in the mirror, I'm going to see a penis growing out of my forehead?' And the doctor says, 'Ah, no, no, no, no. You won't see it. The balls will cover your eyes.'"

Listening on the radio was Tom Taylor of the broadcast trade magazine Inside Radio. Though the audience burst into laughter, Taylor complained that the joke was inappropriate "in that context" because "it is a gather around radio in the living room family show." You can just imagine stuffy GOP operatives huffing about Franken making penis jokes on the beloved "Prairie Home Companion." And yet Franken's wry humor usually wins people over. Later in his "Prairie Home Companion" monologue, it lightened a poignant story about Franken's father's last days. A rabbi requested to visit his father as he lay on his deathbed, Franken told the audience. "I go into the bedroom where he is," Franken tells it. "[My dad's] very weak. It's five days before he died. So [my father's] laying there and I say, 'The rabbi, Rabbi Black, is here and he wants to talk to you.' (Franken shifts to an old Yiddish voice and imitates his father.) "'I don't really know him, but if [the rabbi] feels it'll do him some good.'" The crowd loved it.

"I suspect some people will tell him he has to curb a little bit the tendency to crack wise and that might be difficult to do, but then again you listen to the show and he tries fairly hard to not just do jokes," says Minnesota Democrat Wy Spano. "He tries pretty hard to get into substance and the people in the party know that.

"He can get back to Minnesota-value talk very quickly," Spano continues. "I've seen him perform and been in conversations with him. He doesn't sound all that much like a New Yorker to us and the Minnesota values piece is mostly what he talks about, and I think he probably spends some time making sure that rhetoric is good by checking in with a lot of people around here."

The challenge for Franken, Spano believes, is to appreciate Minnesota's very personal brand of politics. "It's a very tricky job, but [Al Franken] has to be respectful of and nice to all those folks who make up the Democratic Party, the hundred some on the state central committee and the thousands who go to precinct caucuses, all of those that have a little bit of power. He has to be respectful and nice to the folks, but he can't appear to the party to be pandering to them."

Franken's convinced he can do it. He knows his detractors will say he is a joke, a liberal elitist. But he insists, in the end, he'll win over Minnesotans.

"How is Al Franken an elitist compared to George W. Bush?" Franken asks rhetorically. "I grew up in a house that was built in the early '50s that we bought for $19,000 or $11,000," he recalls. "My dad didn't graduate from high school, ended up being a printing salesman, probably never made more than $8,000 a year. My mom sold real estate and did it part time. I don't think we ever had a year where my parents made more than $15,000, but I never felt that I wanted for anything, because I got three squares, could watch as much TV as I wanted, and could go outside and play."

Today, Franken reaches back to his youth to find his home. He speaks of his time in New York as if he is an expatriate. Like fellow Minnesotan F. Scott Fitzgerald, can he really be both New York and Minnesota at the same time? Well, he'll try. And while he has not lived a Minnesota winter for three decades, Franken insists that he feels "more in tune with the majority of the people in Minnesota" than anywhere else. "It's weird, I'm so traditional," he continues. "I've been married 29 years. I arranged my career so I could always be home. Anybody who knows me knows that I live out my beliefs."

"It takes a while to understand what is the appeal of Al Franken because he's not the greatest comedian who ever lived, he's certainly not the greatest talk-show host who ever lived, and he hasn't proven himself yet as a politician," says Michael Harrison, the publisher of the radio trade publication Talkers. "So why Al Franken? That's because, as best I can analyze it, Al Franken is larger than the sum of his parts. There is something about the guy that has credibility." And credibility will be important to Minnesotans. "Early in the campaign, I had my doubts that I could beat Coleman because he was so smooth and I felt I could never be as smooth as him," Ventura says. "And then it dawned on me about five minutes later that I wanted to be just the opposite of him, that I wanted to be rough around the edges, that I didn't want to be so polished."

Certainly, in a time where action star Arnold Schwarzenegger serves as the governor of the most populous U.S. state, Franken's candidacy doesn't seem far-fetched. He has, after all, already helped put Air America on a talk-radio map that's bright red. At the time of the network's launch, of the 15 top political talk-radio shows, 10 were conservative and none were liberal, according to Talkers magazine. Though still dwarfed by his counterparts on the right of radio, Franken has grown from more than 700,000 weekly listeners last spring, to 1.5 million weekly listeners today, not including his recent expansion to Los Angeles, Dallas or Washington, D.C. Still, Rush Limbaugh earns 20 million listeners weekly; Sean Hannity, 12 million. Yet, because of Franken's radio persona, he is arguably the most widely known liberal commentator.

Though he has written five books, including two New York Times No. 1 bestsellers, Franken has radio to thank for his newfound stature. He has beaten back the skeptics. "You could argue that conservative talk lends itself more to talk radio because it speaks in short, easy-to-grasp ideas: lower taxes, less government, and you get off in the Terri Schiavo case, and you get culture of life," says Taylor, of Inside Radio. "These are easier concepts to talk about than a lot of progressive ideas. You know the famous Bush thing, 'I don't do nuance'; progressive talkers do nuance and it tends to slow them down."

Franken does nuance. Unlike many on the political left, he does not support a set troop withdrawal date in Iraq. He would have voted for NAFTA. But bring up healthcare, and the lefty wonk in Franken comes out. "The more I do this show, the more I realize that healthcare is a huge issue," Franken says. "We were just talking about the bankruptcy study and Elizabeth Warren from Harvard did this study and 50 percent of bankruptcy is because of some kind of medical problem and most of that is because we don't have universal healthcare and then you look at reservists returning from Iraq and they don't have healthcare." He says he is not a pure party loyalist. "There are a lot of problems I have with the Democratic Party. That 18 Democrats voted for that bankruptcy bill, that says a lot. That should have been a bill where we said no."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Back in the Air America studio, "The Al Franken Show" is on an advertising break. Franken and his co-host, Katherine Lanpher, are on a tirade. They're livid with the credit card industry.

Lanpher: "I think Big Credit is just as guilty as Big Tobacco."

Franken: "It's predatory lending."

They say credit-card companies coerce Americans into debt and are now lobbying Congress to force Americans to pay that debt through new legislation that makes it significantly harder to declare bankruptcy. Their new guest, Newsweek's Jonathan Alter, argues that this results in Americans essentially becoming creditors' indentured servants. He squarely blames the Republican-controlled Congress for serving the credit-card industry instead of their constituents, pointing out that usury, the lending of money at interest, is forbidden in the Bible. "If you could just get those Republicans to follow the Bible," Franken quips.

That's the paradox of Al Franken. At his core, he remains a comedian. Yet the more he involves himself in politics, the less he wants to be seen as a joke.

"I'm a genuine person. Well, that's easy for me to say," he adds with a chuckle. "I really believe that and I think people will respond to that. Of course they are going to go after me in all kinds of ways, but I'm also a fighter."

Is that what we witnessed with the Dean heckler in New Hampshire?

Franken takes the opportunity to clear up the record.

"I did not body slam him," Franken responds. "The guy made a break for the podium, so I grabbed his legs," he adds, as he squats down and shows how he pinned the heckler. "I wasn't a great wrestler."

But you chose to get on the mat?

"Well, I'm not afraid of anybody."

Including Norm Coleman?

Franken scoffs, "Oh, God, no."

Shares