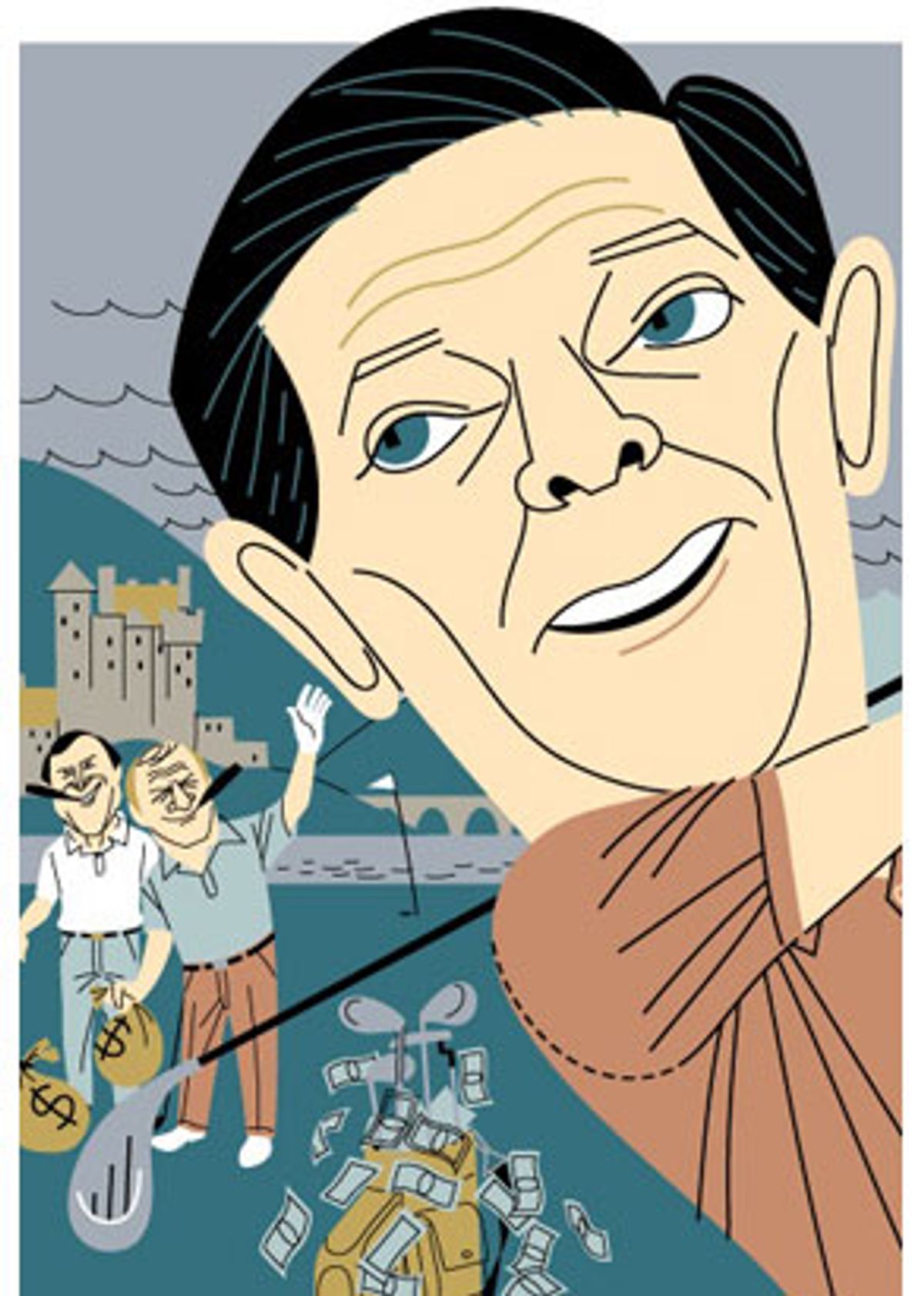

In the fundraising empire that has come to be known as "DeLay Inc.," few figures have been more central to filling the coffers than Warren RoBold. Last September, a Texas grand jury indicted RoBold and two other DeLay aides on charges of illegally raising political funds from corporations and funneling them through one of DeLay's political action committees.

At the same time that RoBold was suspected of laundering corporate money, prior to the 2002 elections, he also raised money for another DeLay PAC to help get the House GOP leader and other Republicans elected to Congress. But RoBold's fundraising duties for DeLay extended beyond the purely political. Tax records also show that back in early 2001, RoBold earned $50,000 to raise corporate donations for DeLay's nonprofit foundation for abused and neglected foster children.

RoBold's multiple fundraising roles for DeLay's various enterprises exemplify the close relationship between DeLay's charity work and his political machinery. Indeed, a review of tax records, financial-disclosure forms and campaign-finance records by Salon from the past five years shows that DeLay's political operatives have routinely worked both for his PACs and his charity organizations. And doing double time, the fundraisers sometimes simultaneously hit up corporations with big stakes in bills before Congress.

Legal experts say such a round robin of political operatives and charity employees does not break the law. But nonprofit watchdogs point out that charity work allows lawmakers and corporations to avoid a raft of rules and disclosure requirements -- thus sidestepping campaign-finance law and congressional ethics guidelines. Rick Cohen, president of the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, has called DeLay a master of combining politics and charity work.

News reports have focused on how effective DeLay's nonprofit work is and whether his charities are being funded by corporations who may be looking for legislative payback on Capitol Hill. The connection between DeLay's political machinery and his charity work, however, is a significant new concern to those who have already suspected that DeLay's nonprofit work is not much more than a cover for corporations to cozy up to DeLay and his congressional allies. Experts agree that the close involvement of DeLay's political operatives and charity fundraisers at the very least creates the appearance that his philanthropic endeavors are but a sideshow to the main event: selling access to politicians.

"Clearly, Delay's charitable activities provide a conduit for him to further his political intentions," Cohen said. Cohen thinks DeLay has run his charity organizations so that "the highest bidders gain crucial face time with and political access to DeLay and his associates -- and to other members of Congress."

"Also questionable is DeLay's use of his political campaign staff to run his charities," Cohen said, "most of whom do not have much specific expertise in the charitable realm but lots of expertise in campaign and PAC fundraising, signaling to potential donors a message that reads as much politics as charity behind the operations of Congressman DeLay's nonprofit endeavors."

The connections between DeLay's political machinery and charity organizations run deep.

Campaign-finance law and congressional ethics rules have contribution limits and disclosure requirements that regulate financial discourse between corporations and lawmakers. Most of these, however, do not apply if that discourse takes place for the stated benefit of a charity. A corporation can't give a lawmaker a $250,000 check over dinner, but it can cut the check to his charity during a lavish weekend charity golf getaway funded by corporations. And the charitable transaction remains anonymous.

"When people blur the lines between campaign-finance law and charitable tax law ... it mixes the intent and it makes it unclear what the real purpose of the organization is, whether it is charitable or political," said Betsy Reid, a research associate at the Urban Institute's Center on Nonprofits and Philanthropy. "It's not that there is a legal problem, or that the groups are not doing good works in the end," Reid said. "It is almost a value-added thing. The charitable sector becomes a value added for the political sector."

In DeLay's case, as he and various political operatives have become the focus of ethics questions, so have the operatives of his charitable organizations -- because they are often the same individuals. For example, the Washington Post reported last Sunday that DeLay's food, telephone and other expenses during a 2000 golf trip to Scotland were billed to the credit card of his former chief of staff Edwin A. Buckham, then a Washington lobbyist.

But Buckham is also connected to DeLay's charities -- he appears as a board member of DeLay's nonprofit for abused and neglected foster children between the summers of 2002 and 2003, tax records show. At that time, Americans for a Republican Majority had just finished sending hundreds of thousands of dollars to Buckham's Alexander Strategy Group for political fundraising, according to campaign finance documents.

The details of that Scotland trip remain murky and may be one focus of an investigation by the House Ethics Committee. In general, golf trips paid for by lobbyists are a violation of House ethics rules, but charities can wine and dine lawmakers pretty freely -- thanks to DeLay. As the first order of business in the 108th Congress, DeLay pushed through in January 2003 a reversal of rules that had barred lawmakers from accepting free trips to charity events. At the time, the DeLay Foundation for Kids was planning its spring golf fundraiser.

It should be said that DeLay and his wife Christine appear to be genuinely committed to helping abused and neglected children. The couple have helped raise three foster kids themselves. DeLay spokesman Dan Allen has always characterized DeLay's charity work as altruistic. "We understand the problems that plague the system and the needs of children that go unmet each day," DeLay and his wife wrote in a letter appearing on their Web site. "It is the mission of the DeLay Foundation for Kids to address the significant needs of abused and neglected children."

But so far, tax records show that DeLay's foundations have spent far more on golf fundraisers than on programs for children. (There are two foundations: The DeLay Foundation for Kids is one; it raises money for a second foundation, Rio Bend, a housing development under construction for foster children.) Over the past four fiscal years, DeLay's foundations have spent almost $600,000 on golf fundraisers at exotic retreats. That is more than seven times what DeLay has so far handed out to unrelated organizations that are actively helping kids, according to tax returns through the most recent filings of June 2004. Golf retreats are the only fundraising activity apparent on the foundations' tax returns.

DeLay's own personal financial-disclosure reports show him traveling to golf in Virginia Beach, West Palm Beach, Miami, and West Hampton, N.Y., at his charities' expense. (An anonymous DeLay foundation official told a reporter from Broward Daily Business Review in 2003 that DeLay would pay his own way to the functions.) The golf trips paid for by the DeLay Foundation for Kids appear in his personal financial-disclosure forms covering 2003, while nothing appears for previous years' golf fundraisers. It is unclear who paid for those trips. His office did not return repeated calls seeking an answer to that question.

At the lavish golf outings, DeLay's foundation has pulled in nearly $7 million from corporate bigwigs. DeLay is not required to reveal the names of contributors to his charity golf outings. That anonymity has fueled speculation from charity watchdogs that the fundraisers are simply an opportunity for lawmakers, corporations and lobbyists to skirt campaign finance and ethics rules as they get together in swank private retreats.

The New York Times reported this month that contributors to the DeLay Foundation for Kids have included AT&T, the Corrections Corporation of America, Exxon Mobil, Limited Brands, and the Southern Company, as well as Bill and Melinda Gates, the Microsoft founder and his wife, and Michael Dell of Dell computers. Tax records show some individual contributions have run up to $250,000. Individual golf outings have raised well over $1 million, according to the IRS documents.

At the charity fundraisers, contributors get to golf with DeLay at places like Key Largo's Ocean Reef Club, described on its Web site as "a very exclusive" 2,000-acre destination country club "known for its Caribbean flair, unparalleled yachting and diving waters, exceptional club service, meetings expertise and wide array of activities." It reportedly has a 4,000-foot lighted private airstrip.

Of the $7 million collected at these events since 2000, tax records for DeLay's two charities show that only about $80,000 has been distributed to various groups doing work to help children. Officials with DeLay's foundation said tax records so far have shown little money being spent on kids because they have been saving it for a major project that is now in progress.

Last December, construction began at DeLay's "Rio Bend," a 50-acre plot of donated cow pasture on the banks of the Brazos River in Richmond, Texas. Construction is well under way on nine homes and a chapel in what the DeLays envision will provide permanent homes and a sense of community for 48 foster children and their families from Fort Bend County. Rio Bend might eventually hold 192 kids. "Right now the foster children move from home to home to home. Our goal is to have a child never be asked to leave Rio Bend," said Jim Jenkins, president of the DeLay Foundation for Kids.

Jenkins said DeLay needed $4 million to break ground at Rio Bend. While tax returns show the DeLay Foundation for Kids had that much cash on hand by the end of the summer of 2003, Jenkins said drainage problems at the site delayed construction for over a year. Future returns filed with the Internal Revenue Service will show the new construction and how much the foundation has started to spend on foster kids. "We had to get to a certain level of funding in order to get under way with the first project. We needed around $4 million to break ground," Jenkins said. "The purpose has always been to support abused and neglected children."

Social service officials in the area said Rio Bend holds promise for helping some foster kids. "This is really unique," said Sam Sipes, president of Lutheran Social Services, the largest provider in Texas of residential services for foster children. His group will screen and place kids at Rio Bend. "The idea behind Rio Bend is it would be a permanent placement for a child," Sipes said. The lack of a consistent home and a supportive community is a serious drawback for the current foster care system in Fort Bend County, which Rio Bend would work to correct. "Those kids typically get bounced from foster family to foster family," and often show up at a new foster home with all their belongings in a trash bag, Sipes said. He said the families will be required to pay rent to live in the 4,000-square-foot homes with seven bedrooms, but it will be far below the market rate.

Typical of DeLay's ethical controversies, even the long-awaited construction at Rio Bend comes with a subplot. The construction company at Rio Bend is Perry Homes. Perry Homes is run by Bob Perry, a major financier of Swift Boat Veterans for Truth. Jenkins said Perry will be paid $26 million if all the construction at Rio Bend goes forward. A Perry spokesman told the Times that he was building the homes at cost. Perry has also donated $44,000 to DeLay and one of his political action committees over the last three election cycles, according an analysis of campaign-finance data for Salon by the Center for Responsive Politics. Perry also donated another $10,000 to DeLay's legal defense fund, DeLay's personal financial-disclosure reports show.

The DeLay Foundation's fundraising is not the first time the congressman's charitable work has come under scrutiny. After some unflattering press, DeLay scuttled a charity event dubbed "Celebrations for Children" that had been set for the Republican National Convention last summer. Bad publicity for the event focused on late parties, yacht cruises and gatherings with lawmakers in luxury suites for donors willing to fork over a half million dollars. The money was supposed to go to the DeLay Foundation for Kids. DeLay's spokesman, Dan Allen, told me that the Celebrations for Children charity is dormant.

Charity fundraising among politicians is bipartisan, of course. Arkansas Democrat Sen. Blanche Lincoln was set to host "Rockin' on the Dock of the Bay" at the Democratic Convention in Boston last summer. Donors were asked to pony up as much as $100,000 to hang out with Democrats at the event, meant to benefit the National Childhood Cancer Foundation. It too was called off after bad publicity. Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist also raised a few eyebrows in the nonprofit world by raising money for his AIDS-related World of Hope charity from donors at a gala during the Republican National Convention.

Some political observers worry that the end of such events -- helping kids -- is not necessarily justified by the means -- politicians hobnobbing with corporate donors -- which can look like a degradation of the political process, typical as such networking is in Washington. While charity fundraising can certainly accomplish good things for good causes, critics say the blending of politics, money and charity is a bad mix. "I think charitable activity is great," said Fred Lewis, president of Campaigns for People, a nonpartisan nonprofit group seeking to ease what he says is the sway of special interests in Texas politics. "But it appears to me that political leaders are getting involved so they can get the good glow from being part of charitable giving, and the corporations are giving for access and influence. I think it is bad for charities and bad for the political process."

Shares