Eight years ago, Camille Peri and Kate Moses hatched a plan on a San Francisco playground: They would start the kind of parenting magazine that they themselves were craving, a publication where how-to articles were banned, developmental milestones and birthday party themes weren't discussed, and Hallmark-inspired notions of motherhood were dispelled. Instead, they envisioned a "Narnia for mothers," a place where parents could drop in at any time of day and get some intellectual refueling. They decided to call their fledgling publication Mothers Who Think in honor of Jane Smiley's essay "Can Mothers Think?" about whether motherhood turns a woman's brain to mush. The site launched as part of Salon in 1997.

In essays like "Expecting the Worst," a takedown of the pregnancy bible "What to Expect When You're Expecting"; an anti-natural childbirth series (with pieces such as "Cut Me Open!" "Give Me Drugs!" and "Take Me to the Hospital!"); and "Molested," by a mother whose son sexually abused his younger brother, Mothers Who Think tackled issues that were ignored by mainstream parenting publications.

In 1999, a collection of essays from the site was published as "Mothers Who Think: Tales of Real-Life Parenting." Ironically, while they were busily working on the Web site and a book about motherhood, Peri (who is married to Salon founder David Talbot) and Moses (who is married to Salon executive editor Gary Kamiya) discovered they had little time to be mothers. A few years ago, Camille and Kate left the Web site to pursue other projects, and Mothers Who Think morphed into the broader Life section at Salon .

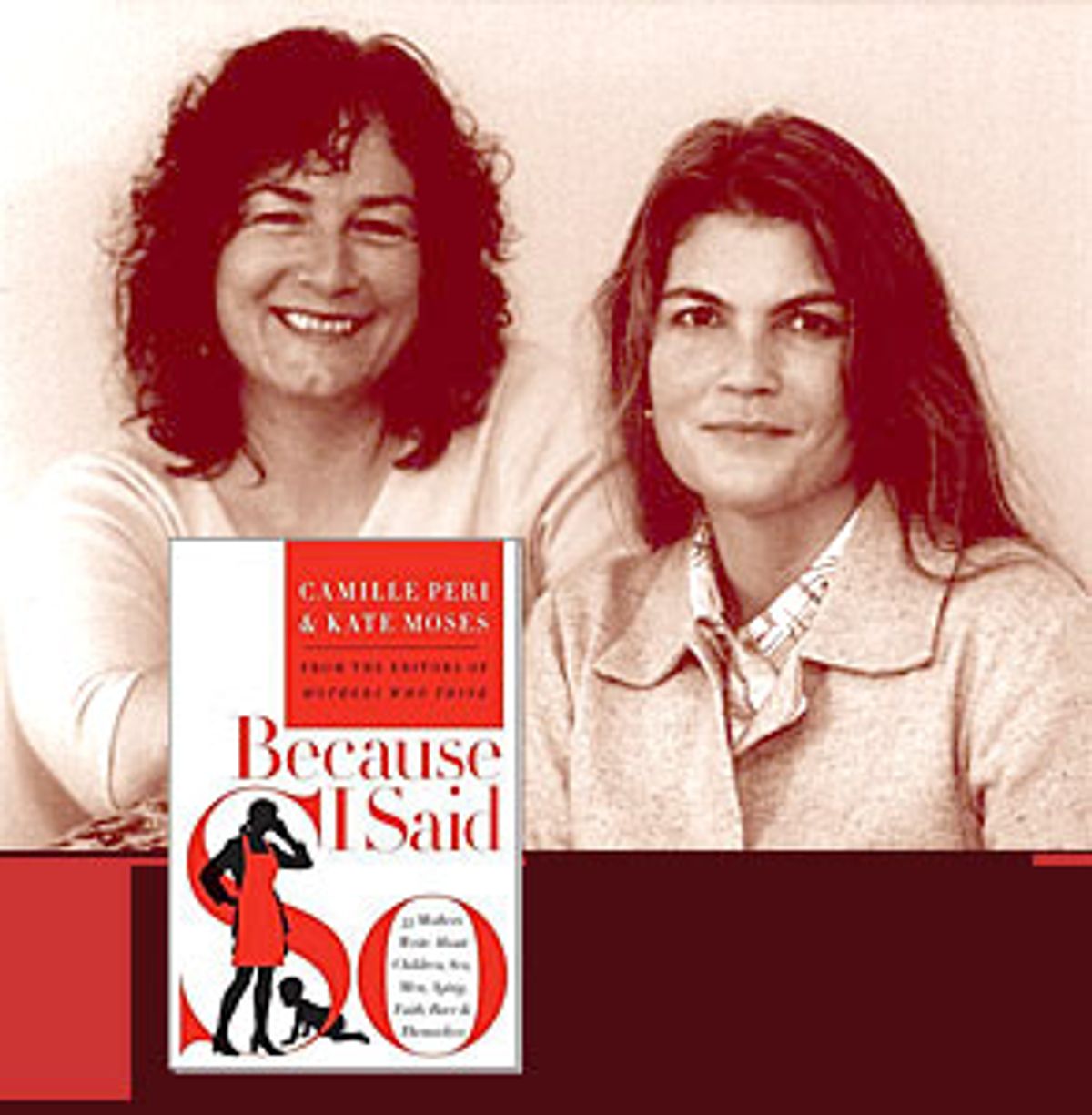

Now Peri and Moses are back with another anthology, "Because I Said So: 33 Mothers Write About Children, Sex, Men, Aging, Faith, Race and Themselves." In the spirit of Mothers Who Think, the collection (some of which was excerpted in Salon last week) includes an eclectic mix of essays, some devastating, some funny, all honest. Mariane Pearl writes about raising her son to be hopeful even though his father, Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl, was killed by terrorists; Andrea Gray reveals that she had to go on food stamps after losing her business, her house and her husband; and Kristin Taylor admits that her only wish after her baby was born was to be "thin, blonde and drunk."

Last week I sat down with my old colleagues to talk about their new book. Camille and I were in Salon's New York office and Kate joined us by phone from San Francisco.

The world is a very different place than it was when you launched Mothers Who Think. You dedicate the book to "children who lost parents to war or terrorism since the turn of the new century" and in your introduction you say that your parenting experiences have now been colored by war, terrorism and environmental havoc. Can you talk about that?

K.M.: It's not like it was a fair or innocent world back when we started Mothers Who Think, but it's become less and less fair and more and more cynical and insensitive. Our kids have almost been forced, because of the media glut, to be more politically aware. Third-graders like my daughter, Celeste, were aware of what was going on politically in the presidential election -- part of that was exciting, and something to be proud of, and in a way I was kind of awed by the sophistication of the kids' thinking -- but it was also really depressing too. It seems like the idea of childhood being protected is really archaic at this point.

C.P.: We grew up in the shadow of the atomic bomb, and when we were kids, there were those duck and cover drills at school. My brother used to say that if there was ever a drill, he was going to run home, because he wanted to die at home. So it wasn't like we didn't have big issues. But I think now it hits kids from everywhere. It's the environment, it's the war, it's race relations not improving fast enough. And I get this sinking feeling because it doesn't seem like we're fixing these problems and that the kids see our despair about it.

When you started Mothers Who Think your kids were toddlers and grade-school kids. Now you both are mothers to teenagers. How have your roles changed?

C.P.: When you first become a parent, I think you are stunned by the amount of stuff you have to do -- changing diapers, nursing, cleaning up projectile vomiting, retrieving Cheerios from every possible location, including inside the creases in your child's neck. The sheer volume of work seems to fill up all the space in your daily life. As they get older, you still have to do a lot of running around, but what becomes more and more clear is that they are who they are, and you become more focused on helping them develop morally and emotionally into adults against the pressures of the outside world.

Mary Morris writes about this beautifully in the book. Before she had a daughter, Mary was completely organized; her idea of heaven was the Hold Everything catalog. But her teenage daughter is just the opposite -- one of my favorite anecdotes is that when she showers, her daughter attaches loose strands of her hair to the bathroom wall. Her messiness, of course, is symbolic of all the chaos children bring into our lives. Mary needed to examine her own childhood and her parents' obsession with order in order for her to let go, to realize that imposing order and control is not necessarily the most important thing you can do for your child's emotional development.

K.M.: Motherhood is a job. With most jobs, the more you do it, the better you get at it. There's a certain learning curve and then you're fine. Motherhood is a job where the learning curve never ends. You're constantly trying to figure out the parameters of what's expected of you.

Did becoming the moms of older kids affect your decision to do this book?

C.P.: Definitely. "Mothers Who Think" was a snapshot of motherhood as we saw it then. But our experience as mothers didn't end with that picture. Since then, our lives, and the lives of our contributors and friends, changed so much. People went through things they never expected to go through -- cancer, divorce, financial ruin, antidepressants, PTA presidencies! And at the same time, the world was changing so fast. Not all of the stories are about women with older kids, but I do think that motherhood becomes richer and more complex as your kids age, and we wanted to do a book that reflected that. Ana Castillo's essay in the book is about being a lifelong feminist and single mother whose college-age son announces to her one day that he is a "hunter of women" and just in it for the chase. Susan Straight discusses the current style among girls -- and in some cases their mothers -- to wear belly-baring fashions and sport tattoos that point the way into their pants. As a parent of older children, you face these kinds of things all the time, and you have to make decisions about how much to expose them to, which values you need to discuss with them, what they are capable of. You need to give them freedom but also to keep them close.

K.M.: One of the phrases we used in the introduction was that, as our children became older and so did we, we felt like we were going over Niagara Falls -- had anyone else survived this before and lived to tell the tale? It seemed like we didn't have a blueprint anymore about how to be mothers.

And how does this collection help lay out a blueprint?

C.P.: There is no blueprint. Mothers Who Think at Salon was kind of the anti-blueprint of parenting, and I think this book, which presents such a vast portrait of modern motherhood, makes it even clearer how useless the one-size-fits-all parenting manuals are. In this book, there are inner-city black moms just trying to make sure their kids get home from school alive, mothers facing the possibility of giving up primary custody of their children in divorce. We don't provide social analysis or prescriptions, but we do present a picture of resilient, spunky mothers taking life by the horns, and it makes me feel less crazy and alone to hear all these voices of different women.

K.M.: Right, that's the rub -- there never was a blueprint! Motherhood is all about flailing around, cobbling it together as you go. But after you've done it for a few years, feeling you've at least got a routine down of balancing your work, your children's needs, and getting the laundry done if not folded, there's a sense of "I get this now." What "Because I Said So" offers is not a blueprint, but a context for mothers. When you hear or read the stories of other mothers, you realize you're not alone in struggling with complicated issues, or in being exhausted and distracted by the myriad little things that you have to manage every day.

The collection has stories about an unwed Muslim mother who is banned by her local mosque, a black mother who is mistaken for her biracial child's nanny, and a Guatemalan woman who came to this country to escape abuse at home. Were you consciously trying to get away from stories that only focused on white, middle-class women, the women who seem to be represented in most of the recent motherhood literature?

C.P.: We did want a really diverse group of women; and by that I mean racially diverse, people from different parenting situations, different economic situations. And then we just asked them what they were passionate about, what's the most central experience in your life. And as a result, I don't think the book feels forced. You don't get the sense from reading it that everyone was asked to write on the same topic. That was important to us because so much of the literature is focused on middle-class women. It's written for middle-class women and that's partly because middle-class women are the book-buying audience. But those books give you a picture of motherhood that's not complete. We wanted to have lots of different voices in the mix to get an accurate portrait of what modern motherhood is. For some of the women, this is the first time they've been in print. We heard about their stories, and we wanted to include them. And so we didn't just go to established writers whose experiences might have been really similar.

K.M.: I hate the word "diverse" -- but we really wanted it to be more realistic as to the variety of experiences of motherhood in America. But that kind of goal can backfire on you if you go out with a tally sheet and try to find a welfare mom and the lesbian mom who used a sperm donor. We didn't do that. And we were lucky because there was this snowball effect -- we couldn't even go back to all the contributors from the first book because it took off so fast. Suddenly, we had more stories than we could even use and we had hardly talked to anyone. Everyone knew someone who had a great story.

When Mothers Who Think launched, it broke new ground. Now, parents have blogs, there seems to be a trendy new motherhood book every day, Judith Warner's book "Perfect Madness" is a bestseller. Do you think the intellectual landscape has improved for mothers?

C.P.: It's funny now, but when we started, the big question was, will mothers go on the Internet; do they have time? We quickly learned that women who were starved for companionship and intelligent conversation would be online reading it whenever they could -- while breast-feeding or in the middle of the night, when they were awake with hot flashes. Now, of course, the Internet has become a major source of information and communication for mothers.

K.M.: I think that the amount of stuff that's out there now is overwhelming. It's hard to weed it all out. But in a way, that's good. It means so many more women are able to connect and to find community that didn't exist before. I remember some of the early letters we got from women who just felt so incredibly isolated but who found companionship on the site. Even though it's sort of a pain to sift though it all to find something truly intelligent, there's also a lot of good stuff.

You both have essays in the book. Camille, you wrote about getting breast cancer and finding solace during your treatment from the hard, blaring rap music that your eldest son Joe listened to. Kate, you wrote about traveling in Egypt and dealing with the devastation of a miscarriage -- at the same time you were dealing with three of your close friends receiving cancer diagnoses. Was it difficult to share such personal stories? Were there truths that you were trying to get at that you hadn't seen written about before?

C.P.: It was really hard, but it was definitely cathartic for me to write about my cancer. I knew that my treatment, losing my hair, wearing a wig, going through radiation -- and my son's new interest in rap, and his political awakening in light of that -- were connected somehow. But I wasn't sure how, until I wrote the story.

It's funny, because in some ways the cancer literature is similar to the motherhood literature -- some of it is really Hallmark card-y. "You'll survive!" "Find your inner peace!" Stuff like that. And I just wanted to write honestly about what it was like because there are funny parts of it -- and you have to have a sense of humor -- while at the same time it's of course really scary, and continues to be scary.

What was funny about it?

For example, my sons pasted pictures of famous bald women -- like Demi Moore in "G.I. Jane" and Sinéad O'Connor -- on the walls for me. My son Joey said I looked like Cal Ripken and how great that was. Molly Ivins once wrote a column about her cancer -- and of course it was humorous because she's Molly Ivins -- and she talked about how doctors, if you're not doing as well as they'd like, act like you're a disappointment to them, like it's your fault. And it was such a relief to read somebody be funny about cancer! Because it's not something most people feel comfortable making jokes about. And sometimes my kids and I, or my husband and I, would make jokes about it and people would laugh politely. But they didn't know how to react.

K.M.: The experience I write about in my essay happened while we were putting this book together. My pregnancy was unexpected, losing the baby was unexpected, my friends' illnesses were unexpected -- and it was very hard for me to suddenly find that I was no longer in control. You think you're just going to be fertile and fruitful but then you realize that just as your children are growing, so are you. It was a shock to me. For so much of your life you're trying not to get pregnant, or you just expect that your body can do things. And then you realize your body has other plans for you.

In the introduction you write about the irony that in deciding to do a book about motherhood, you had to give up almost all of your time with your kids. If you could give one piece of advice to every thinking, working mother -- whether she's at home or at an office or both -- what would it be?

K.M.: I think there's eternal strength in numbers. Just remember there are all of those people out there just like you. Whenever I send an e-mail to another mother at 1 in the morning and I get an e-mail right back, I always feel like I want to cry because it feels so good to know I'm not alone. This is a hard job. As isolated and exhausted as you may feel, knowing that 25 other women on your block are doing the same thing, I think, is comforting.

C.P.: This is a clichi, I know, but the more you can cut to the important stuff, the better off you'll be. We are so lucky to have so many opportunities -- my mother was a housewife who didn't have choices -- and I feel so lucky that I have both of these jobs, and sure it's stressful sometimes, but if you can, spend time with your kids wisely.

K.M.: Buy cookies instead of bake them if you have to! You just have to let go of a lot.

C.P.: Savor the time you do have. Make a certain amount of time with your child every day, whether it's reading or whatever, and then savor it. Of course, they don't always want to spend the quality time with you.

Shares