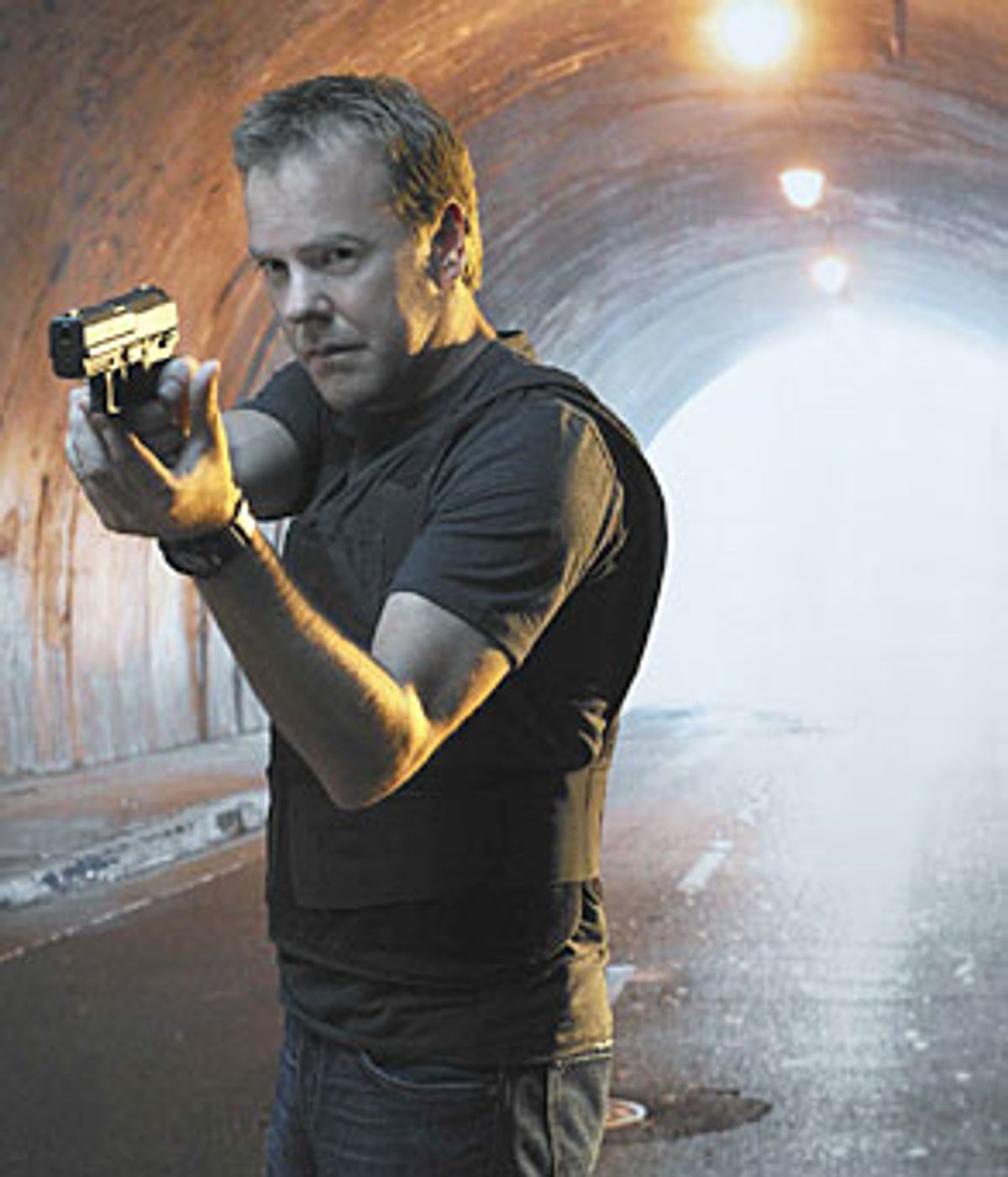

This season of "24" was inevitable. Along with his colleagues at the fictional Counterterrorist Unit (CTU), Jack Bauer, the unrelenting terrorism fighter played to crusading perfection by Kiefer Sutherland, has already faced plots to assassinate politicians, explode suitcase nukes, and launch massive bio-attacks. The CTU has taken out vengeful Serbs, ruthless drug lords and powerful oil interests seeking to manipulate the United States into launching a war in the Middle East. For your freedom, Jack Bauer even got himself addicted to heroin. But that was all foreplay. This year, for the first time, Bauer went up against the real deal: a vast and dedicated network of Islamic terrorists, including domestic sleeper cells, dead set on launching a multi-wave nuclear assault against the U.S. homeland.

Pitting Jack against the jihadists -- for real this time, not like the tease of Season 2 -- gives "24" the story arc it's been crying out for since its November 2001 debut. The secretary of defense is kidnapped, outfitted in a Guantánamo-style orange jumpsuit, and marched into a terrorist show trial broadcast live over the Internet. Defense contractors who have sold weapons to enemies of the United States deploy a team of mercenaries to kill government agents. Nuclear reactors remotely controlled by the terrorists melt down in the midst of densely populated areas. The only force able to protect America from total destruction, naturally, is CTU.

CTU's ridiculously capable agents fish through oceans of information to discover imminent attacks, lurk behind every security camera on every street corner, and have a license to torture detainees if it means preventing a nuclear nightmare. Executive producer Howard Gordon has described "24" as catering to the public's post-9/11 "fear-based wish fulfillment" for protectors like Jack Bauer, who don't hesitate to go to extremes. That's one way of putting it. Another is that "24" is war-on-terror porn.

Don't tell that to Gordon's colleagues. For the people behind "24," the sheer fact that the show deals with jihadist terrorism during "Day Four," as this fourth season is known, demonstrates the show's gritty verisimilitude.

"For it to have any believability and resonance, we had to deal in the world we're living with, with the terrorists and the jihadists," co-creator Joel Surnow recently told the Washington Times.

But don't tell that to the show's legion of security-wonk fans. For many of them, it's precisely the absurdity of "24" that makes the show so irresistible. "That's what we love about it," notes "24" addict Juliette Kayyem, a former Justice Department official who directs Harvard University's national security program. "Nothing seems to make sense if you actually piece it together." Adds Roger Cressey, a former White House counterterrorism aide in the Clinton and Bush administrations who admits to TiVo-ing the last couple of episodes: "Although the real world doesn't offer anything nearly as fast, or as good or bad, it's entertaining as all hell."

It's not just the official-sounding gibberish (in one of the show's finest word salads, the CTU chief instructs her staff to "double-source all intel through Homeland Security and CIA," which is sublimely meaningless). Many of the show's central elements strain plausibility to the breaking point. Every good genre show requires some suspension of disbelief. "24," one of the best, demands a cryogenic freeze.

So -- which scenarios in "24" should you really find scary?

Would this season's bad guy, Habib Marwan, really ally his Islamist terrorists with non-jihadis to attack the United States?

It depends what the non-jihadis would be used for. Jihadist or Islamist cells have been known to employ or otherwise utilize non-jihadis for money laundering, document forgery and other tasks to facilitate an attack. For example, Hezbollah operatives have linked up with non-Muslim organized-crime syndicates in the poorly policed Triple Frontier region of South America, where Paraguay, Brazil and Argentina meet, generating a source of revenue for the militant Shiite organization. Similarly, the Madrid train-station bombers financed their attacks largely through selling hashish, which has made European counterterrorism officials fear increased cooperation between jihadis and gangsters. "That part of '24' is not far-fetched," says Cressey -- though the show is "taking it to an extreme."

That's because these contacts with outsiders tend to occur on the periphery of jihadist activity, and not without the network's "being very sure to seal off knowledge of vital details" about a particular plot, according to terrorism analyst Jonathan Stevenson of the International Institute for Strategic Studies. What's more, arrests of terrorism suspects in Europe indicate that non-jihadis enlisted to assist with even marginal aspects of financing or travel facilitation are often radicalized Muslims, demonstrating the reluctance jihadists feel in venturing too far beyond the ranks of the committed. Even if jihadis turned to outsiders for assistance in obtaining WMD, they would be unlikely to involve them in any plot to actually use such weapons.

Marwan, by contrast, not only uses non-jihadis liberally but also makes them central to his operations. Most egregiously, Marwan turns to Mitch Anderson, a flaxen-haired disgraced Air Force pilot, to hijack an F-117A stealth fighter (stay with us here) and attack Air Force One, a critical step in an attempt to gain control of a nuclear warhead and sow fear into the hearts of Americans. More generally, from Chinese nuclear physicists to African-American spies at CTU to unscrupulous U.S. defense contractors, Marwan's hiring policy may earn a commendation from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, but it is pretty unrealistic.

Could an operation as extensive as Marwan's remain a secret?

First and foremost among the reasons why jihadists don't often stray far outside their ranks to pull off terrorist attacks is operational security. A high-ranking Yemeni operative of al-Qaida known as Khallad told U.S. interrogators that outside of a willingness to commit suicide, the most important criterion in selecting participants for the 9/11 attacks was the patience necessary to endure years' worth of planning and training while escaping detection. Opening an ambitious series of operations to individuals not bonded to a terror cell through strong ideological ties is an invitation to have a plot penetrated and compromised. It's no accident that the 9/11 hijackers restricted their contacts when inside the U.S. to as few people as necessary. Indeed, a Spanish police informant reportedly warned his contacts months before the Madrid bombings that the train station was being targeted -- information he said he acquired from his pot-dealing brother-in-law.

And even if Marwan's plan relied exclusively on jihadists, it wouldn't prevent careless errors. Key al-Qaida operative Ramzi bin al-Shibh informed Mohammed Atta during a July 2001 meeting in Madrid that Osama bin Laden wanted the attacks on New York and Washington expedited out of fear that having too many U.S.-based operatives for too long would jeopardize the plot. The detention of Zacarias Moussaoui shows bin Laden was right to worry. Within three days of Moussaoui's arrival at flight school in Eagan, Minn., in August 2001, INS agents arrested him on immigration charges. He immediately attracted the suspicion of his flight instructor through his stated desire to "take off and land" a Boeing 747 and his disinterest in earning a commercial pilot's license, not to mention his cash payment of an $8,300 training fee. While the FBI was never able to unspool information from Moussaoui into an understanding of the imminent 9/11 attack -- which the 9/11 Commission considers a missed opportunity to thwart the plot -- bin al-Shibh believes that bin Laden and 9/11 architect Khalid Sheikh Mohammed might have actually called off the operation had they known beforehand that Moussaoui was in custody.

Unlike bin Laden, Marwan isn't so troubled by operational security. He films his terrorist communiqué in the back room of a trendy nightclub -- so hot that its dance floor is pulsing during the worst terrorist attacks in American history! -- which his agents equipped with special catacombs for hasty exits. Marwan's sprawling network inside is abuzz with activity that should have made it low-hanging fruit for the data-mining juggernaut of CTU. The Araz family transformed an abandoned factory on the outskirts of L.A. into the terrorist equivalent of an office building, complete with secure Internet servers. A Midwestern cell stands ready to overwhelm a military convoy carrying a nuclear warhead at practically a moment's notice. While Dina Araz tells CTU that the cells didn't communicate with one another, Marwan checks in with everyone constantly. "Spot communication may not be such a problem, but maintaining cells that communicate regularly and crystallize a number of attacks probably would be more difficult," Stevenson says. "The more you communicate given operations, the more likely it is that the security authorities will find out."

Ironically, the inability of CTU to pick up on the terrorists' myriad sloppiness might lend an element of realism to "24" -- that is, good old-fashioned incompetence. If there's ever a 24 Commission, CTU director Erin Driscoll is in serious trouble.

What if the terrorists got their hands on the "nuclear football"?

By the time they did, it would be useless. On a day of spectacular attacks -- from the kidnapping and show trial of Defense Secretary James Heller to the meltdown of a San Gabriel nuclear reactor (there isn't one, in case you were wondering) -- by far the most traumatic is the airborne destruction of Air Force One. While incapacitating the president of the United States obviously has its utility if you're a terrorist, for Marwan it's merely a fringe benefit. What he's really after is the nuclear football, the briefcase containing the attack options and authorization codes for the nation's nuclear arsenal that never leaves the president's side. Blowing up Air Force One while the president is onboard and recovering the football from the smoldering wreckage just seemed the easiest path from point A to point B.

Why Marwan goes to the trouble is a mystery. Leave aside for a moment the question whether the titanium interior of the most important attaché case in history could survive a missile strike and then a 30,000-foot plummet. In the event of an attack on the president, says Globalsecurity.org's John Pike, the football "would have been inactivated immediately. [Then] the football that the vice president carries is hot." From the perspective of national-security procedure, the issue isn't the football, but the chain of command for the stewardship of its contents. If a scenario like Marwan's really played out, antiques collectors would have a greater use for a purloined nuclear football than terrorists would. As Pike puts it, "You might be able to sell it on eBay as a curiosity."

It gets weirder. Marwan manages to rip a page out of the football's codebook. He quickly informs his Midwestern operatives that it contains the location of a warhead in transit to a facility in Iowa and instructs his team to intercept the nuke. That's sheer fantasy. The football's crucial contents are the Single Integrated Options Plan -- the menu for ordering a nuclear attack à la carte -- and the authentication mechanisms to instruct the National Military Command Center at the Pentagon that the time is at hand. "It does not concern itself with day-to-day movements of anything," says a knowledgeable former senior administration official. "And it does not contain specific information needed to unlock a single nuclear weapon."

OK, but still... couldn't the terrorists detonate a U.S. warhead if they possessed one?

While it's not impossible, it's extremely improbable. Since at least the Kennedy administration, physical mechanisms have existed on the bombs themselves to prevent unintended use. The chief safeguard is what's known as a Permissive Action Link (PAL), which prevents the arming or launching of the weapon "until the insertion of a prescribed discrete code or combination," according to the Department of Defense. The encrypted electronic PAL codes are created and changed periodically by the National Security Agency and kept at tightly secured places in a small number of military command centers. (As noted, the nuclear football is irrelevant here, since it doesn't contain PAL codes.) Though PAL designs are highly classified and have changed significantly over the decades, all are constructed to interrupt the firing process, and some essentially destroy the weapon if a certain number of incorrect codes are entered into the weapon's code box.

And the PAL isn't the only safeguard against unintended use that the bombs possess: Environmental sensing devices ensure the nuke's firing circuits are interrupted unless it achieves a velocity, trajectory or altitude consistent with duly authorized use. Most weapons, especially the more recently developed nukes, use something called insensitive high explosives to compress the nuclear material for a chain reaction -- "insensitive" because "if you drop it, pound it, or subject it to some trauma, it's not going to go off," says Robert S. Norris, a nuclear expert with the National Resources Defense Council.

So Marwan's out of luck. On "24," he employs an engineer, Sabir, who's designed a "chip" that can control the warhead's triggering device -- which, to the extent it means anything, means disabling or overriding the PAL. "Absolutely not," says the ex-official. If a terrorist doesn't have the classified, secured and constantly changing PAL codes (and good luck with that one) he's not activating the warhead. "They've thought this through," says Pike. "They've spent considerable effort to make sure that if nuclear weapons are detonated, it's the result of deliberate national policy."

But if Marwan thought creatively, he might have a slim chance of pulling off a detonation. His engineers do have another way around the PAL: They could take the bomb apart and design another. "If you had a terrorist also intimately familiar -- and I mean intimately familiar, not vaguely familiar -- [with bomb designs] and if he had access to a weapon for very long period of time, then it is not inconceivable that the individual could obtain some nuclear yield," the former senior official cautions. However, even for such expert nuclear engineers, figuring out how to take the bomb apart and rejigger it would require "weeks" of work, and the team would only have a few hours before Jack Bauer captured or killed them all.

Alternatively, Marwan could decide to forgo a nuclear yield altogether and opt for the much easier route of using the plutonium inside the warhead for a dirty bomb. One of his terrorists makes a cursory mention of obtaining a "legacy" warhead, which raises the prospect that the stolen bomb contains conventional high explosive and not the insensitive kind. As the name suggests, conventional explosives in nuclear weapons are vulnerable to high temperatures, meaning the terrorists could subject the warhead to a fire in the hope of detonating the explosives. In such a case, it's highly unlikely that the explosion could trigger a chain reaction and hence a nuclear blast, but the plutonium would disperse and contaminate the surrounding area -- the classic dirty-bomb scenario.

Could the nation's nuclear facilities be subject to a terrorist-induced meltdown?

Nope. If "24's" producers intended to irritate the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, they succeeded. The show's drama kicks off with Marwan's agents stealing a device called the Override, the creation of a defense contractor that adds an external safeguard preventing a civilian nuclear reactor from melting down. According to "24," the Override can also induce a meltdown if a savvy hacker can successfully launch a cyberattack on reactor security. Once accomplished, the Override can actually get control of all nuclear plants in the U.S., creating an environmental disaster so intense that the country will be brought to its knees.

In response to a deluge of worried phone calls after the episode aired, the NRC released a calm-down statement throwing cold water on the idea that any device "could remotely operate all 104 U.S. nuclear power plants via the Internet." And that's because "there is no central nervous system that controls all the nation's nuclear power plants," Cressey explains. "It just doesn't work that way." Unfortunately for the NRC, as the show progressed, the (fictitious) San Gabriel reactor melted down, causing mass (television) chaos and prompting a gigantic (imaginary) evacuation. NRC released another statement: "Nuclear power plants in the United States have redundant safety systems and several very robust physical barriers as well as well-established emergency plans that help ensure people living near these plants are kept safe." When I called for an elaboration, a very polite spokeswoman, Sue Gagner, made it clear that the NRC prefers to put the "dramatic fiction" of "24" behind it.

That's hardly surprising. NRC has had the specter of cyberattack hanging over its head since at least 1997, when the Pentagon organized a famous cyber war game that demonstrated the vulnerability of civilian infrastructure to online assault. In January 2003, an online worm called Slammer disabled a safety monitoring system at the Davis-Besse nuclear power plant in Ohio after a contractor for its owner, FirstEnergy Nuclear, installed an unprotected high-speed connection at the plant to FirstEnergy's internal network. Davis-Besse had been shut down for a year, but even if it was operating, the damage caused by Slammer would have been marginal -- and could neither have caused a meltdown nor spread to another reactor.

Even so, NRC has been beefing up its cybersecurity guidelines: Its most recent draft, issued in December, specifically warns against establishing interconnectivity between plant networks and outside networks to prevent another Davis-Besse. Since the NRC's guidelines aren't mandatory, a terrorist like Marwan could try to exploit laxity by a negligent plant operator, but it's incredibly remote that he would be able to cause significant damage to one reactor through a cyberattack -- let to alone all of them.

Could a bleeding heart civil-liberties lawyer and an uppity judge stop a terrorism interrogation in progress?

Not even if this was the United States of Sweden. One of the show's most dramatic twists comes when an associate of Marwan's, an ex-Marine named Joe Prado, is arrested and brought to CTU for interrogation -- which, in the world of CTU, means torture. Marwan, who's now got his nuclear warhead, needs Prado to stay silent, so he turns to a sure-fire ally: liberals. A Marwan aide informs a legal advocacy group, "Amnesty Global," that CTU is about to torture an innocent American citizen. Within 15 minutes (!) of Prado's after-midnight arrest, a self-righteous and impeccably tailored shyster named David Weiss arrives at CTU brandishing a court order protecting Prado. Immediately Jack Bauer has two people he'd like to torture (three if you count the absent judge, who explains to CTU division chief Bill Buchanan that since Prado isn't a known terrorist, the interrogation must proceed with kid gloves if at all). When President Logan won't immediately intercede, Weiss marches Prado out of CTU safe and sound. (Don't worry -- once the lawyer drives away, Jack breaks Prado's fingers until he talks.)

There are a lot of implausible scenarios in "24." The idea of a judge stopping an interrogation in progress might be the most outlandish yet. "The chances a judge would step in seem relatively low, if not impossible," says Kayyem. It's tremendously difficult to determine what's legal in the world of "24," but if the Amnesty Global lawyer pressed his case to the judge based on the prospect of Prado's imminent torture, even to the most flagrantly liberal activist judge on the bench, he would have a high evidentiary bar to clear. "You can't just walk into court and make the accusation of torture and spring the guy," says the ACLU's Emily Whitfield, another "24" addict. "The judge will say, 'What's the basis?'" And, of course, the basis is -- well, an anonymous tip from a terrorist, which wouldn't get Prado out of CTU even if a pinko attorney had on hand a stack of circumstantial evidence suggesting that abuse occurs in terrorism detentions. Then there's the small matter of the political climate. Whichever judge issues an order to stop the interrogation of a terror suspect while the United States is under attack had better be prepared for an angry mob led by Sen. John Cornyn to rip him from limb to limb.

There's a brief scene where Buchanan contends that the PATRIOT Act duly authorizes Prado's detention. Actually, it wouldn't: The act's expansions of the government's detention powers don't extend to U.S. citizens like Prado. But the feds have other tools on hand. For example, Prado could be held for questioning as a material witness in CTU's ongoing investigation of the day's attacks, since he was discovered meeting with a man on a terrorist watch list. Judges tend to defer to the government's rationale for detaining individuals in such cases.

OK, but wouldn't a useful-idiot civil libertarian at least try to free Prado? According to Whitfield, whose organization is clearly the model for Amnesty Global, if the ACLU learned of a case like Prado's, "we might make a few calls to see if the person's being held and if a public defender has been appointed... We tend to do the big-picture stuff. We're not a criminal law firm." Of course, by the time the ACLU or anyone else learned of Prado's detention, his initial interrogation would have long since ended.

Could government agents really be so reliant on torture -- even for use on American citizens?

Not constitutionally. In the United States portrayed on "24," the law is an abstraction. If CTU were a real government agency, its agents would be criminals. President Charles Logan is appalled to hear that CTU wants authorization to torture an American citizen (Prado), suggesting that on "24," as in the real world, constitutional prohibitions on torture apply; when Jack does it anyway, Logan orders the Secret Service to arrest him. Yet all throughout the day, Bauer and his CTU colleagues torture practically everyone -- including U.S. citizens -- believed to have knowledge of the terrorist conspiracy. When suspected of concealing crucial information, Secretary of Defense Heller's son Richard is subjected to sensory deprivation, a CTU analyst named Sarah is repeatedly Tasered, and Heller's son-in-law Paul is electrocuted. And if President Logan's conscience is shocked, it's apparently because the accidental commander in chief is unfamiliar with what CTU really does. When Heller's daughter Audrey is jarred by watching Jack torture her husband, the defense secretary consoles her by saying, "That's his job ... We need people like that."

Sure, a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little TV critics. But to take the United States as shown on "24" on its own terms, CTU possesses some nebulous authority to torture recalcitrant detainees it considers to have intelligence value. The source for its authority is obscure -- otherwise, no judge would have intervened to stop Prado's brutal interrogation. But considering the nonchalance of old-pro Heller and the CTU staff, combined with the horror of newcomer Logan, it would seem that the previous administration of President Keeler -- perhaps in response to the terrorist attacks of the first three seasons of the show -- granted CTU some ability to torture U.S. citizens. That wouldn't resolve where Keeler got the authority from -- if Congress passed a law sanctioning torture on U.S. soil, presumably Logan wouldn't have had a problem with the Prado case, dubious constitutionality aside -- but it serves as the most plausible explanation for CTU's procedures. As Kayyem puts it, on the show "there's no law." Certainly not as we'd recognize it.

Instead, there's "protocol." When Audrey learns that Jack tortured Prado, she admonishes him that he can't just "violate protocol" -- that is, the president's wishes. Never mind that there's a court order to prevent Prado from being abused. For "24," the relevant authority is the policy decision of the commander in chief, not the law. Whether the writers of the show intend it or not, the logic on display is reminiscent of the argument made by then-White House counsel Alberto Gonzales and attorneys from the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel in early 2002: that the Constitution grants the president maximum authority in wartime to defend the country as he sees fit, and that the stated intentions of the president (to treat al-Qaida and Taliban detainees humanely to the extent consistent with military necessity) are a fit substitute for binding law. Sure, President Bush's aides were debating how to treat noncitizen enemy combatants -- and later, in the infamous (and repudiated) Justice Department memo of August 2002 defining torture narrowly, what interrogation techniques were permissible overseas. But "24" suggests that after a few more terrorist attacks, the slope may slip further.

So does "24" endorse torture?

Yes. It's true that the torture of Richard, Sarah and Paul doesn't result in any useful information -- and of the three, only left-wing Richard can't forgive CTU for the abuse. Sarah and Paul, by contrast, seem to brush off their unfortunate treatment in recognition that torture can yield reliable intelligence, even if mistakes occur. Hence, as soon as Jack shoots a Marwan associate named Sherak in the leg, the once-recalcitrant terrorist bellows that his comrades are targeting the secretary of defense, who's almost instantaneously kidnapped. (If only Jack had shot him earlier!) Most significantly, Prado's torture yields specific and accurate information on Marwan's whereabouts just after the nuclear warhead is stolen. When Logan's orders to arrest Jack for torturing Prado allow Marwan to escape, the new president loses all confidence in his abilities to defend the country during the unfolding crisis and essentially abdicates his office. Messages don't often come clearer than that.

Or more misleading. First, "24" presents the least likely and most academic of interrogation scenarios, the "ticking bomb" case, where an apprehended suspect is likely to have information that can potentially forestall an imminent attack and the only reasonable way of making him talk is to abuse him. These conditions are practically never met in the real world, and making legal (or, in the show's case, "protocol-based") allowances for ticking-bomb cases inclines interrogators to use in routine cases a tool intended for exceptional ones. Such abuses led the Israeli Supreme Court in 1999 to ban the use of "moderate physical and psychological pressure" that a state commission established in 1987 for ticking-bomb cases.

Second, information gleaned from torture is typically worthless. As Magnus Ranstorp, a terrorism expert at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland argues, the most useful intelligence on terrorism comes from "a broader repertoire" of largely psychological tools. CTU's repertoire is almost uniformly physical, which often says more about the quality of the interrogator than the toughness of the detainee. Chris Mackey, a military interrogator who squeezed intelligence from al-Qaida and Taliban detainees in Afghanistan, recalls in his memoir "The Interrogators" how his instructors at Fort Huachuca "hammered home the idea that prisoners being tortured or mentally coerced will say anything, absolutely anything, to stop the pain." Even if we were to posit a real-life ticking bomb case -- with that ticking bomb being a nuclear detonation -- the interrogation methods that "24" says are responsible will most likely endanger American lives by producing bogus information. Not for nothing did John Negroponte, Bush's new intelligence czar, state at his confirmation hearing last month that "not only is torture illegal and reprehensible, but even if it were not so, I don't think it's an effective way of producing useful information."

If we're to take Gordon's theory of "24" as wish-fulfillment seriously, that may be one of the great ironies of the show. When measuring the distance between counterterrorism reality and fantasy, all you have to do, in Kayyem's words, is "compare John Negroponte and Kiefer Sutherland." Who would have thought that Negroponte would emerge from that matchup looking better?

Shares