In 1994, Rachel DeWoskin left Columbia University with a degree in English and no idea of what to do with the rest of her life. So, of course, she did the practical thing -- she moved to Beijing.

Living abroad as a recent grad is a trade-off, an exchange of one problem (choosing a career) for another (ordering the vegetarian plate and getting stuck with the rooster head). In DeWoskin's case, things were even more complicated. Shortly after arriving and settling into the grind at an American P.R. firm, she met a man who decided her white skin was all the qualification she needed to act in a soap opera about American girls in Beijing. "I was like, 'Hell, no,'" she remembers. But it didn't take too many more late nights at the office, drafting reports, to change her mind.

The show's title, "Foreign Babes in Beijing," says it all. Two American exchange students (one played by a German) come to China and pursue romances with Chinese men. There's the predictable good girl-bad girl split: the blond Louisa, who loves Chinese culture almost as much as she loves her Chinese boyfriend, and the lusty, slutty, brunet Jiexi, the "dishanze" (mistress, or "third") who steals the honorable Tianming away from his hardworking wife and homeland. As Jiexi, DeWoskin got some lessons in soap opera acting -- for one low-tech slow-motion sequence, she was directed to actually run slowly, arms flailing and all -- and earned the affection of 6 million fans eager to catch a glimpse of the strange new expatriates just beginning to come into Beijing. And that was before syndication.

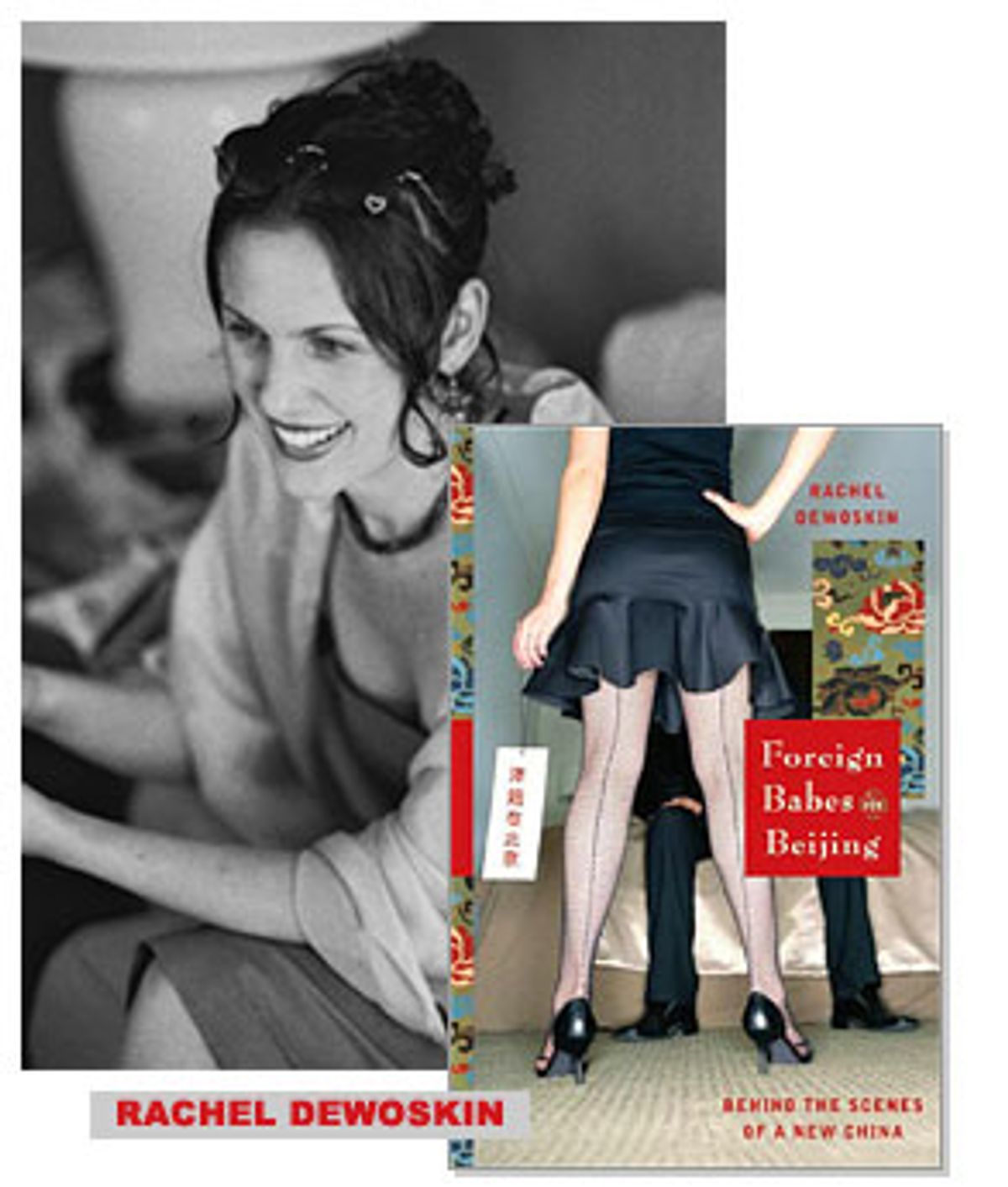

This month, DeWoskin's account of her years as a foreign babe -- and playing one on TV -- hits the shelves. "Foreign Babes in Beijing: Behind the Scenes of a New China" is a double story, a diaristic account of her experiences abroad interwoven with musings on Chinese and American politics and pop culture. "Before the 'Foreign Babes' script, I had never heard the stereotype that Chinese are lazy," a typical observation goes. "But Chinese believe that Americans believe it." She remembers (with a chuckle) the director of photography's wise appraisal of her hysterical attempt at a sex scene -- "Foreign babes are tigers!" "Funny," she drily notes, "I had always thought that was a stereotype of Eastern women."

Being both "Du Ruiqiu" (her name from college Chinese classes, which turned out to have the unfortunate meaning of "bumper harvest") and "Jiexi" -- not to mention "Rachel" -- lends DeWoskin the perspective to collapse the personal and political to great, and occasionally hilarious, effect. She's never afraid to poke fun at, as she says, "the monster in the mirror," and makes herself the first target of all criticisms, as well as primary perpetrator of all gaffes. As a well-to-do Westerner who is paid more handsomely than any of the Chinese employed at her P.R. firm, for instance, she's uncomfortable negotiating her "Foreign Babes" contract, so she settles for a laughable $80 per episode (this for a "Desperate Housewives"-caliber sensation that made its already rich producers even richer). She later learns that "they all found the foreign babes naive, and understood that we were willing to act for free because it was an honor to be on Chinese television, because we wanted to be pretty, and because we were deeply insecure." And, she concedes, "They were likely right."

DeWoskin insists that her book is not political, that she can only speak for herself. Yet even peripherally, the story of Sino-U.S. relations in the 1990s, a decade of previously unimagined opening, unfolds. American readers are treated to all the tiny details that make politics human: the mid-'90s, when the American media was focusing on the human-rights abuses against students in Tiananmen Square and the Chinese media was focusing on the human-rights abuses against Rodney King; the introduction of McDonald's and China's obesity "crisis" (it calls itself a nation of "xiao pangzi," little fatties); the relationships between her Chinese and American friends that were strained by the U.S. bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, Yugoslavia. The book succeeds not by putting forth any conclusion -- deciding that McDonald's is good or bad for Beijing -- but by throwing the politics that govern our everyday lives into relief, drawing attention to all of the tics and habits and assumptions that we, at home, so often fail to notice.

I met DeWoskin at a cafe near Columbia University, where her husband, Zayd, is finishing his Ph.D. We talked about the difficulties of writing about yourself, why American humor doesn't translate into Chinese, and Beijing, where she still spends half the year.

You wrote "Foreign Babes" almost a decade after your time in China. What made you decide to do it now?

I felt like my Chinese friends had such incredibly interesting lives, and I came back to America and immediately perceived that the idea of China in America was very much like the idea of America in China, which is to say, not accurate by my standards. You know, I would go to the bank teller to cash a Chinese check, and she'd be like, "Do the communists stop you and question you?" I just felt bewildered that Americans didn't have a better sense of how hip and engaging Beijing is, and how international young Chinese are, that in fact they're just like young Americans -- that they're edgy and they're interesting and they're sexy and they're spiking their hair and having premarital sex and doing all these things. It's a very hip environment, and I felt defensive that everyone here thought China was nerdy and caught in 1949.

I think of the book as the story of my friends. It's not a sordid, tawdry kind of kiss-and-tell. Mainly I left those things out, not because I'm coy, but because I don't think they're that interesting. It would be so self-loving -- I mean, you go live in China for 10 years or five years, and write a story of yourself?

In the book, you insist that the Chinese are sophisticated television viewers. They're used to Peking Opera and socialist melodrama. They know the histrionics aren't real, but yet they come up to you and think you're Jiexi.

Well, they think I'm Jiexi in the same way that they think Courtney Cox is Monica, or they think Jennifer Aniston is Rachel, or they think Teri Hatcher is a desperate housewife. People knew that I was an actress, but TV is a fantasy to be lived through, so in spite of the fact that they knew I wasn't Jiexi, really, they wanted me to be in love with Tianming anyway. It was such a lovely story that they wanted it to be true. But I argued, and I still argue, that Chinese audiences are sophisticated consumers of moral drama.

Do you think that they were sophisticated consumers of the political angle of the show, too, in terms of you standing in for all those loose, Western women?

I do. When the Western media accused the show of being a propaganda machine, I think the question that it failed to ask -- first of all, it failed to watch the show -- but the question that it finally failed to ask was, if the show is a propaganda machine, what message does it impart?

Louisa, the good girl, the blonde, of course, becomes an angelic China scholar, and lives out the rest of her days in the courtyard with her Chinese family, being a perfect daughter-in-law and rolling dumplings. And Jiexi breaks the heart of her Chinese family by taking Tianming away with her to America. But she redeems herself by calling the father-in-law "Father." And honestly, when the two of us leave for America in the last episode, it's a beautiful scene of exodus. It was not a xenophobic, panicked scene about me taking Tianming out of China.

So there are two ways to see the show.

Exactly. But both of them involve a long-term commitment to the West. I mean, in Jiexi's case, we got married, and I sacrificed everything for true love. And Louisa sacrificed America so that she could go to China. If you think that the show has a political message at all, it seems to me that the message is that we're going to continue this engagement. And the fact is that, on the street, people followed me around and bought whatever condiments I was buying. So the message to teenage girls was this liberated, free, strong, independent woman -- we want to be like her.

That's such a flexible idea of nationality -- it seems like Louisa actually becomes Chinese. It's hard to imagine a show in America that would so openly celebrate a white person identifying with another race. It would be too tense.

Well, what's tense in China is relationships between Western men and Chinese women. They would never have depicted that on television, although that's the reality of it. Most interracial relationships were not beautiful white babes with virile People's Liberation Army poster boys. Although, increasingly they're becoming that way. And you know, the depictions of Chinese men in America have historically been so hostile and overwrought, it's turning the tables a little bit to have the white girls be exotic and the Chinese men be macho. I was into it. I felt like we could relieve Eastern women momentarily of the burden of being mysterious. And for Chinese men to be kind of the heroes of propaganda films was very attractive to me. And the truth about Chinese men in my experience -- although I never gave this kind of sound bite in China because I was too defensive -- is that they're just like men everywhere. There's just a huge spectrum and they vary tremendously. And many of them are extremely macho and they're not inscrutable Orientals and they're not Charlie Chans and they're not houseboys. When people accused the show of promoting stereotypes, I couldn't help but say, "Have you ever watched American television? Have you seen Long Duk Dong recently?"

There's also an increasing interest in America in Japanese yakuza films and all kinds of Asian gang movies, sort of a hot Asian gangster thing --

No question. Even Jackie Chan. He's not a perfect example, but Bruce Lee -- any of these martial arts guys. I mean, "Hero" and "House of Flying Daggers," "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon" -- all of these movies are promoting a new macho China. And you know, China is becoming more and more of a superpower, so it makes sense that its men would be increasingly depicted as tough.

In your writing, you frequently create humor by relating a faux pas or mishap of communication just before you give the reader knowledge that you acquired much later. There's the time, for example, when you say "circumcised" instead of "strict." But how funny were all those miscommunications at the time?

Most of them were quite funny. Often in China, I was embarrassed by my own difficult grasp on the language. For me, fluency and eloquence -- these are the staples of my life. The thing I care most about is language. And I care very much about how words fit together and which ones I choose and other people choose. Grammar mistakes light up in my mind, as in Word. And so in China I just felt powerless in that regard. I had no nuance, and I had no ability to communicate subtleties, and I felt crippled by that. And in a way I'm grateful, because it was so humbling. Anybody who's self-loving needs to take a trip out of his own language and try to communicate. It taught me more about the power of language and it taught me something about my own capabilities, the limits of my own competencies. Some of my gaffes were incredibly embarrassing at the time, but even then I had an inkling of perspective. I mean, in order to have a reasonable life abroad, you have to have a sense of humor. And I've always been self-deprecating. That part was effortless for me.

But it seems like that self-deprecating irony doesn't always translate into Chinese.

It never does. Most of the humor doesn't translate. The two things I never could get and still can't get are sense of humor and gift-giving. I never once told a joke that any of my Chinese friends thought was funny, and I never gave a gift that anybody liked.

Still, in your writing, you're never afraid to make cultural differences a source of humor, to draw attention to the ways that the Chinese and Americans are different.

I tried not to generalize so much in the book. One of the things I came to think, not only while living there but also while writing the book, is that writers ask questions and propagandists answer them. So I never felt like I was in a position to answer questions about China particularly, and -- this is an important component of good poetry -- if you present an anecdote and then you make it universal in a way that's funny or attractive, you've been successful. If you present an anecdote and you do nothing to make it universal, you've been self-loving, because your anecdote isn't interesting unless it applies to other people. And yet at the same time, if you make it too general, then you're stereotyping.

One of the things I made an effort to do in the book was to choose characters -- choose my friends who are anti-stereotype. And the more people I met, the more I realized that even though certain patterns exist in terms of cultural behaviors, on an individual level it's just like my American friends. And that shouldn't have been a revelation, but it was for me. And if you're honest about that kind of thing, it is funny.

As the book progresses, the Chinese and Americans portrayed seem to understand each other more. But at the end, those relationships are damaged by the NATO bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, and it feels like a step backward. Did you see progress in terms of cross-cultural understanding?

I would say yes, there was progress. On the ground, it looks like coming to certain understandings. My feeling overall about China is that a policy of engagement, all the time, with positive interchange and people on the ground, is the best policy. And in a small sense, friendships in China create this. This is how we're building Sino-U.S. relations. I don't think it's a top-down process. I think it's bottom-up. I think it's grass-roots efforts, like when people go and live there. And I tell all of my students to go abroad. I think it's important. I think it's important for Americans to be in the world promoting a picture of America that isn't the picture our government promotes. What we don't want to do is go backward.

That's kind of what it feels like we're doing sometimes. It had to be really strange for you to come back to the U.S. right before Sept. 11.

It was very meaningful. When I came back to America, my perspective on the U.S. had changed entirely. In a way, China gave me a view not only of China, but also of America, and what it meant to be American. You know, you have to have an external reference point. China gave me that. I watched the American news as a sophisticated consumer of moral drama, rather than a credulous fan of CNN. And I began to see patterns, and I began to see similarities between our newspapers and their newspapers; our television broadcasts and their television broadcasts; our state-run media and their state-run media. And yes, those parallels became more and more dramatic as America moved into the 2000s.

How is the media different? How are political conversations different?

You know, the Chinese language is very flexible. Lawyers complain that it's vague, but fans of it talk about how flexible it is. In Chinese, you can "leave three sides open." People don't pin you into awkward conversations -- it's a place about keeping things open, keeping things flexible, "sideways negotiation," sideways conversation.

We don't do that in America.

No, we're very confrontational. It's funny, I really feel like I've toned that down. And I'm glad. I feel like China benefited me personally; my personality is better for having been to China.

Shares