I had a rental car and a little time to kill in Lincoln, Neb., one sunny afternoon this week, so I headed south on Interstate 77 to State Highway S55H, known locally as "Hallam Road." I drove west, more or less retracing the route that Larry Ohs, a local attorney, longtime resident of Lincoln, and storm spotter for the local SkyWarn Network, had taken in his Chevy Suburban on the evening of May 22, 2004. Ohs is one of many trained SkyWarn storm spotters who volunteer themselves for the unglamorous duty of driving to points along a grid system in Lancaster County, parking their vehicles, and watching to see what develops by way of big weather. At 8:32 p.m. that night last year, Ohs passed through the town of Hallam, which was pitched in darkness; a powerful storm moving in from the southwest had knocked out its power grid. Not a soul stirred. Ohs didn't know it at the time, but he would be the last person to see the village of Hallam intact. Minutes after arriving at his spotter location, the largest tornado in history, a two-and-a-half-mile-wide cyclone, came rumbling to within a thousand yards of Larry Ohs and his Suburban. To this day, the sound of a passing freight train can set his heart racing.

Hallam was flattened, but a great deal else was also damaged along a 52-mile swath of rural Nebraska. Beyond the town of Wilber, to the southwest, livestock was killed or scattered, fences were knocked down, farms and farm equipment completely destroyed, the hard work of generations of Nebraska farmers brought low. And on the next day, another kind of storm kicked up: the media storm.

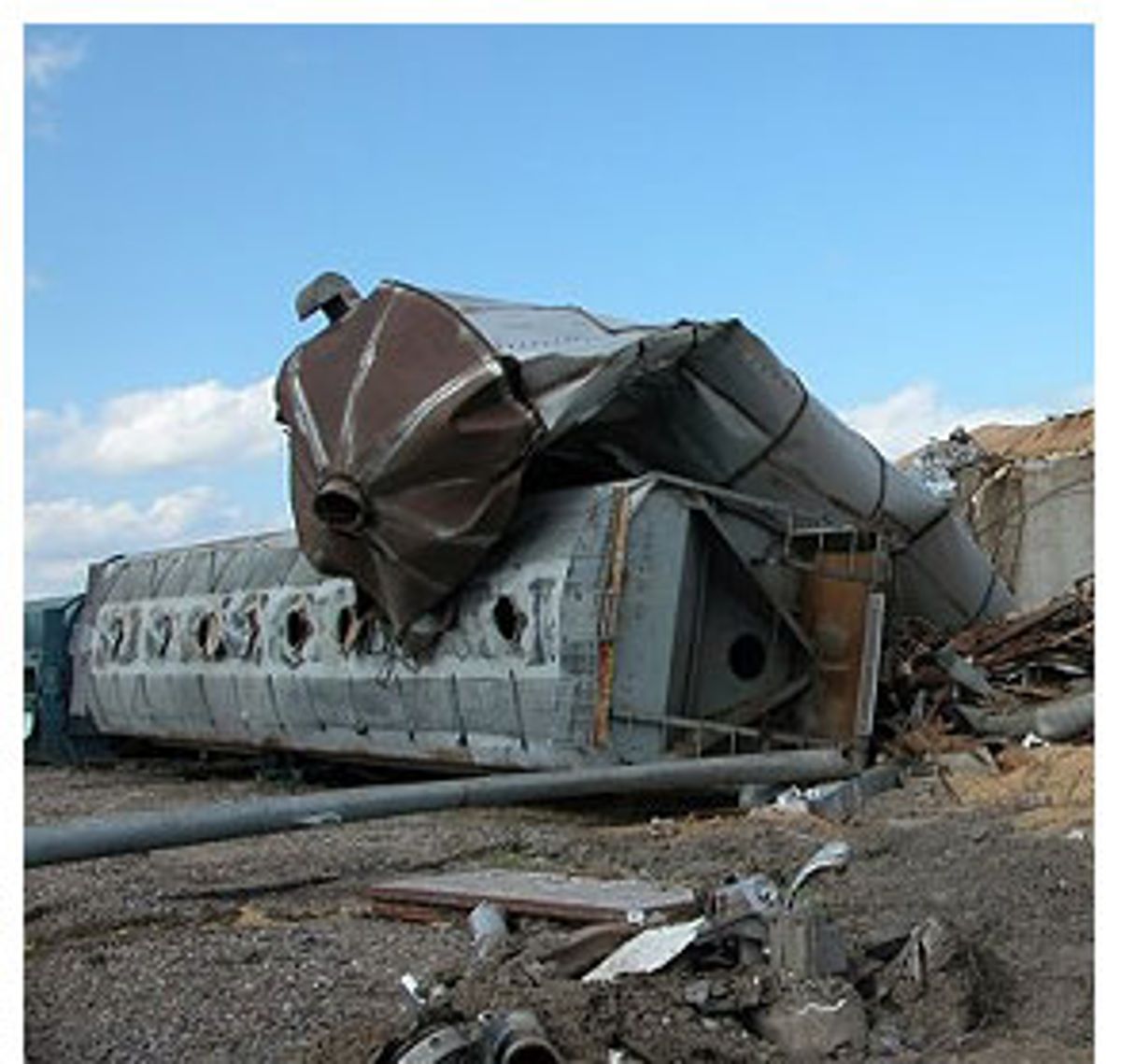

Wilber and nearly a dozen other small towns had to make way for Hallam. The images of destruction beamed across the nation were unbelievable -- 300-foot grain elevators stoved-in like crushed and discarded beer cans; a freight train toppled for as far as one could see; beautiful old houses completely flattened or lifted off their foundations. To many Hallam residents, the media presence was an unsolicited and largely unwanted second wave of attention. But as the flurry continued, some who had suffered beyond the glare of the cable trucks that lined Hallam Road for a mile began to take umbrage. "It was all about Hallam," one resident of Wilber observed, a bit ruefully, as if to say that at least the losses suffered by the residents of Hallam had been recognized. Against the media's big, blathering embrace, everyone else along the damage path, it seemed, was left to gather what remained of their ruined farms, alone and unheralded. A subtle episode of disaster envy began to emerge just beneath the surface of everyday conversation, starting with the very name of the tornado itself.

Typically, a tornado is marked and named, tagged and recorded into history, by taking the name of the town it destroys -- Woodward (Oklahoma), Xenia (Ohio), or Wichita Falls (Texas)-- or the town nearest to its destructive path. In North America, where more than a thousand tornadoes descend each year, a seemingly endless list of place names emerges, some of them etched in regional memory, others more obscure but offering a strange litany of destruction, like a catalog of ships from the Iliad: the Siren tornado (Siren, Wis., where the tornado sirens failed to function); the Happy tornado (Happy, Texas, where one person was killed); the Manchester tornado (Manchester, S.D., a hamlet that was completely erased from the earth). It speaks to the power of names and naming -- and the anxiety of being left unnamed, of being left behind, written out of history -- that a mild contretemps arose about the "Hallam tornado." Nobody from the Wilber area, for instance, begrudged Hallam's place in the limelight -- the town had sustained the most damage and had lost one of its own, beloved citizens (Elaine Focken, an elderly woman who was struck by falling debris). Even so, many non-Hallam residents cast their allegiances in small ways -- by calling the storm "the Hallam/Wilber tornado," for instance, the locution like two freight cars coupled together, in order to make a subtle but important point.

But what of Daykin or Swanton? What of Clatonia and Firth? Would Palmyra and Hickman and Bennet and Holland and Cortland and Western be forever forgotten? As the one-year anniversary of May 22 approached, Theresa Gomez of Caring Communities, a FEMA-sponsored disaster relief organization that specializes in "community healing, mental health and disaster recovery," began to suggest that the event be commemorated in some way. Hallam's initial response, it seemed, was to wrap a protective cloak around itself. "They wanted to be by themselves -- without the media," recalled Cindy Togstad, whose farmhouse near Wilber was lifted up and flung a hundred yards by the tornado and whose two sons, trapped in the family basement, were famously rescued by the Twister Sisters, Peggy Willenberg and Melanie Metz-Trockman, storm chasers from Minneapolis. At the urging of Wilber resident Jana Nicholson, Togstad began to organize an entirely different memorial event, one that would, in effect, form a coalition of the unsung -- of tornado survivors who, finally, on May 22 of this year, gathered to tell their stories in something that they called "A Celebration of Re-Building," which took place at the American Legion Park in Wilber.

On the morning of the celebration, I caught up with Cindy Togstad -- who is short and pretty, with deep blue eyes and a ready laugh -- organizing door prizes. Local companies had donated, among other things, a grandmother clock, a stained-glass American flag, a carpet cleaner, cash prizes that would be awarded during an all-day Bingo game, and T-shirts that said "Been to Oz and Back" on one side, followed, on the back, by a punch line: "And all I have left is this darn T-shirt." All raffle proceeds would go to the Wilber disaster relief fund. Togstad was full of energy, this woman who had lost almost everything last year. She noted, dryly, that the two Lincoln television stations were going to broadcast live all day -- from Hallam. "All we got was an announcement on the local TV that we were having a barbecue." She seemed too busy, however, to linger over such slights. The Shriner clowns were coming. There were hot dog buns to order. A bounce house for the kids to set up. The Twister Sisters would soon be arriving, as would the Wilber Fire Department, the Sheriff's K-9 unit, and a National Geographic camera crew to film it all.

But what to call the event that was being commemorated? Some simply punted, settling upon the bland but inoffensive "southeastern Nebraska tornado," which, according to climatologist Kenneth F. Dewey, had almost no chance of surviving as a name. History is unkind. For good or ill, the storm that affected so many lives would probably be remembered as the "Hallam tornado." A year ago Sunday, that tornado had removed most of Hallam, had picked up its contents and blown it for miles where it began raining down from the clouds -- canceled bank checks were found as far away as Omaha. And in the aftermath, a town's destruction, its near complete removal, had strangely put it once and for all on the map.

Shares