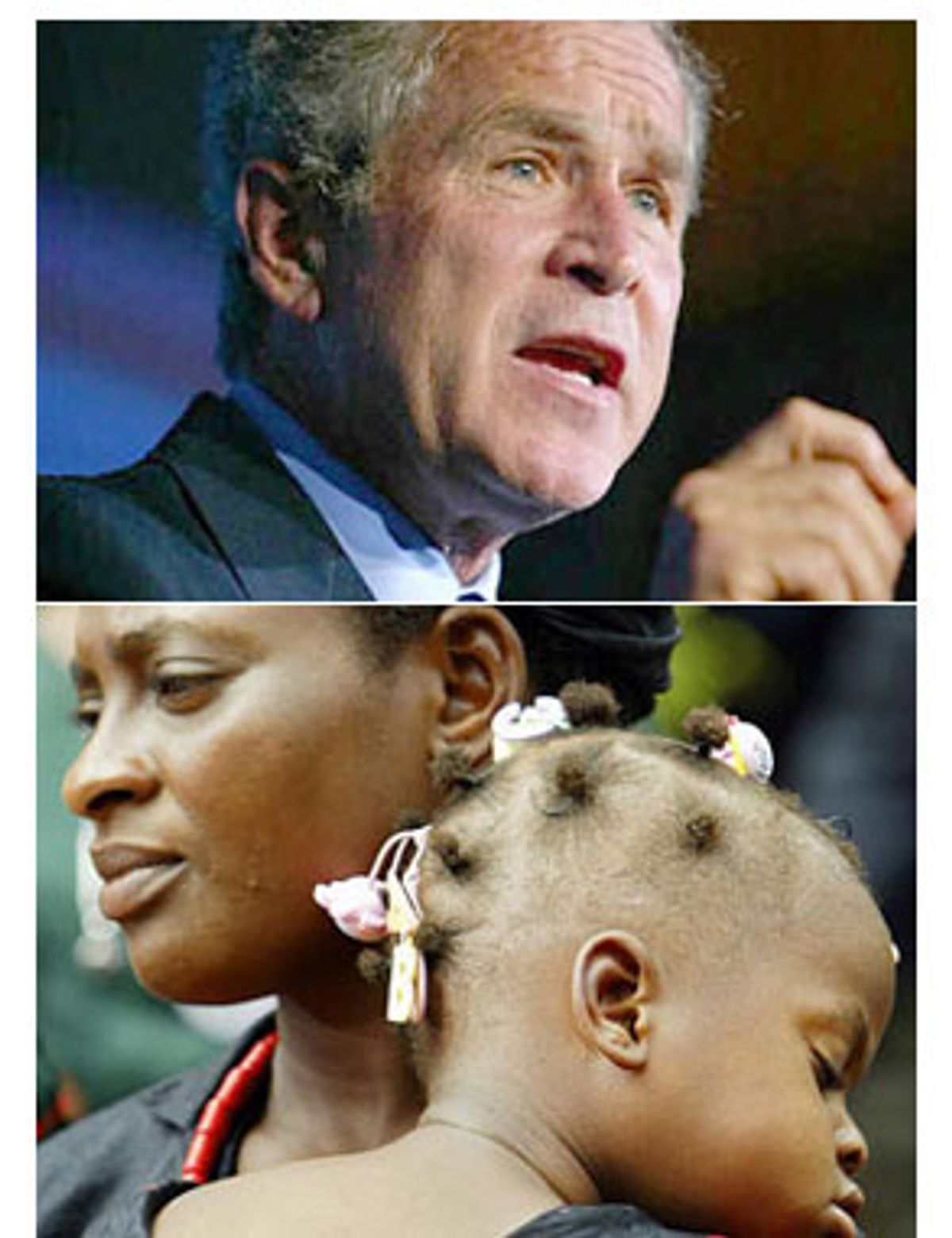

When President Bush introduced his global AIDS initiative in January 2003 -- "a work of mercy beyond all current international efforts," he called it -- the plan certainly sounded promising. Bush pledged to spend $15 billion over five years to provide life-saving drugs to at least 2 million people with HIV, prevent 7 million new infections, and care for the sick and orphaned in 15 countries. Most of the money would go to sub-Saharan Africa, home to the majority of the world's nearly 40 million people living with HIV and AIDS. "I believe God has called us into action," Bush declared during a trip to Uganda in 2003. "We are a great nation. We're a wealthy nation. We have a responsibility to help a neighbor in need, a brother and sister in crisis."

Dubbed the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR, the agenda provided the administration with much-needed P.R. at the very moment it was preparing to defy international will by invading Iraq. But from the start, Bush has been inexplicably stingy and mind-bogglingly slow to act.

Despite rhetoric about our moral duty to fight AIDS -- Bush has likened PEPFAR to the Marshall Plan, the Berlin airlift, and the Peace Corps -- the president has not committed the funds necessary to meaningfully tackle the crisis and even opposed attempts in Congress to fully fund his initiative. And much of the money Bush has provided is being derailed into moralistic and unproven programs that make abstinence the centerpiece of HIV prevention. Few Americans realize that the money flowing into disease-ravaged locales is being diverted to serve a right-wing political agenda -- at the cost of untold numbers of lives.

Bush requested only $2 billion for PEPFAR in its first year, at least a billion less than one might have expected, given his pledge. Then, when Congress decided to approve $400 million more than the president asked for, Bush unsuccessfully fought to block the increase. By the time the plan was fully implemented, nearly a year and a half had passed since the president had announced it -- a costly delay in fighting an epidemic that claims 8,500 lives every day.

As of this month, PEPFAR is expected to provide anti-retroviral treatment for an estimated 200,000 people, mainly in sub-Saharan Africa. "I think those numbers are cause for encouragement and optimism," Bush's global AIDS czar, Ambassador Randall Tobias, told me recently. "I think there's reason to believe this can be done." But in a region where 25.4 million people living with HIV are desperate for treatment, it's difficult to feel elated about our progress -- or our commitment.

Tobias, a former CEO of Eli Lilly and Co., has found himself under international fire as Bush's AIDS emissary. Last year, Tobias was booed at the International AIDS Conference in Bangkok by protesters carrying signs that read: "He's lying." And as a former pharmaceutical executive, he's taken heat for the administration's insistence on relying on brand-name AIDS drugs instead of generics that are two to four times cheaper. "There comes a moment in time," says Stephen Lewis, the U.N. secretary-general's special envoy for HIV/AIDS in Africa, "when you stop bowing to Big Pharma and recognize that the human imperative at stake of keeping people alive requires that we embrace low-cost generics because we can treat so many more people." Lewis rejects the administration's argument that generics are less safe and effective than brand-name drugs. "Everyone understands that the position which is taken [by the U.S. government] significantly supports major pharmaceutical companies," he said.

As it stands, what we're doing barely factors into the disease's devastating arithmetic. Twelve million people died of AIDS in Bush's first term. "Bush's initiative is going slow," says Dr. Paul Zeitz, executive director of Global AIDS Alliance. "We're not coming near meeting the need or what is possible. If I were Ambassador Tobias, I wouldn't be defending this current framework. I'd be going back to the president and saying: I know we have a role to play. Why not ramp this up so we can stop the dying?"

The truth is, we are doing something, but not nearly what we could be doing. Although other priorities dwarf Bush's AIDS program -- $136 billion in new corporate tax breaks, for example -- the United States is the largest single donor to the global AIDS fight. But it would be a tremendous embarrassment if we weren't: The United States accounts for one-third of the global GDP.

The administration insists it will meet its goals by 2008, saying it planned all along to gradually "ramp up" the program. This year, the United States is spending $2.8 billion on PEPFAR, and Bush has asked for $3.2 billion in 2006. But public-health experts say it looks increasingly unlikely that Bush will fulfill his promise of $15 billion over five years -- and that even if he does, the money will fall far short of what is needed.

According to UNAIDS, a partnership involving the World Bank and nine other international aid groups, the world needs to spend $20 billion a year by 2007 to wage an effective war against AIDS. What Bush proposes to spend annually, if funding remains constant, is less than half the $6.6 billion that America would be expected to contribute based on the size of its economy. "The fact that the United States can spend $300 billion on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan but cannot find a relative pittance to rescue the human condition in Africa -- there is something profoundly out of whack about that," Lewis says.

The president's AIDS initiative, like his invasion of Iraq, is a go-it-alone affair that ignores the clear global consensus on how to fight AIDS. In launching his own initiative, Bush has shifted the bulk of U.S. money away from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, an international financing mechanism established before PEPFAR and widely recognized as the best way to distribute AIDS funds. "Bush is starving the fund," Zeitz says. "It's despicable, frankly."

Unlike PEPFAR, which focuses on 15 countries -- inexplicably excluding the AIDS-ravaged nations of Swaziland and Lesotho among others -- the Global Fund has committed funds to 128 countries. Economist Jeffrey Sachs, special advisor to U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan, recognizes the Bush administration's modus operandi. "This group is so convinced they have to do everything by themselves even though they often know the least about the issue," he said. "They reinvent everything -- reinvent it wrong at the beginning, learn along the way, explain that it takes time, and here we are." Where we are, unfortunately, is much like where we were two and half years ago.

But the failures of Bush's global AIDS policy go beyond how much money is being spent. Perhaps even more disturbing is how it's being spent. Overlooking the grim realities on the ground, Bush is using AIDS funds to place religion over science, promoting abstinence and monogamy over comprehensive sex education that includes information about and access to condoms. This should be no surprise, given the administration's track record. Yet it is still shocking to observe an administration that claims to be acting in the name of morality consigning tens of thousands, perhaps millions, of people to death because of its policies.

In 2002, America joined Libya, Sudan, Iran, Iraq and Syria -- a veritable axis of the unenlightened -- to scuttle an endorsement of sex education from a global declaration on children's health. Before overseas groups can receive U.S. funding, the Bush administration requires them to take a "loyalty oath" to condemn prostitution -- a provision that AIDS workers say further stigmatizes a population in need of HIV education and treatment. Brazil recently became the first country to rebel against the oath, announcing in May that it was rejecting $40 million in AIDS grants from the administration. "What we're doing is imposing a really misguided and ill-informed ideology on top of a public health crisis," says Jodi Jacobson, executive director of the Center for Health and Gender Equity in Takoma Park, Md.

Just as U.S. abstinence-only programs that push partial or false information on teens have doubled under Bush, so are such morality-driven programs cropping up under U.S. auspices in places like Africa -- where the stakes are much higher and a lack of vital information can kill. PEPFAR is fast becoming equated with a notorious emphasis on abstinence education -- nearly $1 billion of Bush's global AIDS pledge is earmarked for abstinence promotion. Bush's plan calls for an ABC approach to HIV prevention -- which stands for "Abstinence, Being faithful, Condom use," but the administration is stressing the "A." In its first year, PEPFAR spent more than half of the $92 million earmarked to prevent sexual transmission on promoting abstinence programs. "It's only a matter of time before the impact of abstinence-only programs can be measured in needless new HIV infections," says Jonathan Cohen, an HIV/AIDS researcher with Human Rights Watch.

Administration officials deny inappropriately stressing abstinence over all else, and point out that the epidemic worsened in Africa and other nations even with condom promotion. "If there is a sense of focus on abstinence until marriage now, it's because we've never been focused on these important things," said Dr. Mark Dybul, assistant U.S. global AIDS coordinator. But there is a good reason global AIDS experts haven't focused on abstinence: Scientific evidence shows no indication that trying to persuade young people to abstain from sex at the expense of condom education reduces the spread of HIV. Studies show that such programs actually increase risk by discouraging contraceptive use.

What's more, focusing on abstinence and monogamy ignores the reality facing young women and girls in Africa and other impoverished regions, who are often infected by wandering husbands or forced to have sex in exchange for food or shelter. Among 15- to 24-year-olds in sub-Saharan Africa, studies show, more than three times as many young women are infected with HIV as young men. Preaching about abstinence and faithfulness to girls and women in risky situations "can't be made sense of on any level," Jacobson says. "It's not only contrary to public-health best practices, it's contrary to common sense and contrary to human rights principles."

The emphasis on morality is being driven by social conservatives who have made spreading the gospel of abstinence and monogamy to Africans their primary mission. "Condoms promote promiscuity," says Derek Gordon of the evangelical Christian group Focus on the Family. "When you give a teen a condom, it gives them a license to go out and have sex." At a congressional hearing in April, Rep. Henry Hyde, R-Ill., threatened to cut funding for organizations that promote condoms. "The best defense for preventing HIV transmission is practicing abstinence and being mutually faithful to a non-infected partner," Hyde declared. And under a proposal being pushed by Hyde and his Republican colleagues on Capitol Hill, Tobias would be given the power to divert even more money toward promoting abstinence. "All [conservatives] can think about is making Africans abstinent and monogamous," says a Democratic staffer. "It's the crassest form of international social engineering you could imagine."

Nowhere is the effort by conservative Republicans to turn back the clock on sex education more pronounced than in Uganda. By aggressively promoting condom use and sex education, Uganda has managed to cut its HIV rate from 15 percent of the population to barely 6 percent during the past decade, making it Africa's biggest success story. Social conservatives argue that an emphasis on abstinence and monogamy drove down Uganda's HIV prevalence -- and if only other African nations could adopt such rigid moral standards, they would see similar success. While it's true that partner reduction may well have helped lower Uganda's HIV rates, the role of abstinence has been distorted and overblown by evangelicals seeking to control U.S. AIDS funds.

Under pressure from the Bush administration, Uganda has taken a dangerous turn toward an abstinence-only approach. In April, the country's Ministry of Education banned the promotion and distribution of condoms in public schools. To make matters worse, the government has even engineered a nationwide shortage of condoms, issuing a recall of all state-supplied condoms and impounding boxes of condoms imported from other countries at the airport, claiming they need to be tested for quality control. As of this year, a top health official announced, the government will "be less involved in condom importation but more involved in awareness campaigns: abstinence and behavior change."

The Bush administration is supporting the shift by pumping $10 million into abstinence-only programs in Uganda. "One can put a dollar figure on the political pressure," says Cohen, who has closely studied the initiatives in Uganda. "Groups know the more they talk about abstinence, the more they'll get U.S. funding. And they fear that if they talk about condoms they'll lose funding -- or, worse, get kicked out of the country."

Tobias issued written guidelines to PEPFAR partners in January that spell out the administration's agenda. Groups that receive U.S. funding, Tobias warned, should not target youth with messages that present abstinence and condoms as "equally viable, alternative choices." Zeitz of Global AIDS Alliance has dubbed the document "Vomitus Maximus." He says, "I get physically ill when I read it. It has the biggest influence over how people are acting in the field."

The anti-condom order issued by Tobias is already having a chilling effect among the groups most effective at combating AIDS. Population Services International, a major U.S. contractor with years of experience in HIV prevention, says it can no longer promote condoms to youth in Uganda, Zambia and Namibia because of PEPFAR rules. "That's worrisome," says PSI spokesman David Olson. "The evidence shows they're having sex. You can disapprove of that, but you can't deny it's happening." What's more, conservatives are attacking PSI for promoting condoms -- a campaign that prevented an estimated 800,000 cases of HIV last year. Focus on the Family recently denounced PSI as a "shady" and "sordid" organization that is leading Africans into immorality.

And in April, conservative Republicans in the House invited Martin Ssempa, a Ugandan minister, to Capitol Hill, to berate PSI for "promoting promiscuity and condoms" in his country. "Today, we face a new enemy in the fight against HIV/AIDS, not only in Uganda but in all the other African countries," Ssempa told the House International Relations Committee. "That enemy is the Western belief that condoms can end the HIV/AIDS epidemic." The attacks on PSI have become so extreme and ideological that even some Republicans think they've gone too far: Utah Sen. Orrin Hatch sent a letter to USAID last month expressing dismay over "inaccurate information" being spread about PSI. Still, this year, U.S. funding for PSI has been reduced for the first time.

Religious conservatives intent on hijacking global AIDS prevention funds are putting heavy pressure on legislators and the Bush administration to strip funding from established public-health organizations like PSI in favor of faith-based groups that promote a moralistic agenda. Some faith-based organizations have long, admirable histories of working in Africa. But soon, even these groups could face a litmus test -- if they don't strictly adhere to abstinence promotion, they could lose funding to smaller, more ideological groups. "Throw out the window any public-health test," Jacobson said.

Groups that support the president's religious agenda, meanwhile, are beginning to receive money that has traditionally been devoted to more experienced organizations. The Children's AIDS Fund, a well-connected conservative organization, received roughly $10 million last fall to promote abstinence-only programs overseas -- even though the group was deemed "not suitable for funding" by an expert review panel. Fresh Ministries, a Florida organization with little experience in tackling AIDS, also received $10 million. "Bush has enacted policies that will redirect millions of dollars away from groups that have experience fighting HIV and AIDS and toward groups that don't but are members of his religious constituency," Cohen says.

In the end, say public-health experts, the administration's diversion of funds from tried-and-true HIV-prevention methods is more than a misguided experiment -- it's a deadly game of Russian roulette that could mark a calamitous turn in Africa's attempts to get a handle on the AIDS epidemic.

It's hard to imagine how the health crisis could get worse in sub-Saharan Africa, where life expectancies have plummeted below 40 in some nations and more than 12 million children have been orphaned by AIDS. HIV prevalence has been somewhat stable in recent years, but experts are worried that could be disguising the worst phases of the epidemic, with roughly the same number of people getting newly infected with HIV and dying of AIDS. Africa's fight against AIDS is a tragedy that, with all of the resources at our disposal, we could be doing something about -- but so far, we're not. "People will look back and say, Why didn't they stop the dying?" Zeitz says. "Why don't we show our compassionate selves? What kind of country are we?"

Shares