Early on the morning of Nov. 3, 2004, and one day after voting for John Kerry, I turned on my computer to find an e-mail awaiting me from my mother’s cousin, who lives in Tehran, Iran. In all caps, the subject line jeered, “No More Ab-e-Taliban for You!” His message was short, composed at noon during the depth of my night, as I fitfully slept awaiting the U.S. election results: “Your candidate has lost everything, and you have lost Ab-e-Taliban!”

He was referring to a drink I fell in love with last summer on my first visit to my mother’s homeland of Iran. During that month, my cousin (whose name I’ve chosen not to reveal) and I had argued politics with fierce but playful energy on daily walks around Tehran. These were hours-long journeys, through hideous heat and traffic, to the oases of sidewalk shops displaying rows of blenders filled with vivid concoctions of mulberries and ice, bananas and milk, or different varieties of melon. I would always choose the “Ab-e-Taliban” (which means “Taliban water”), made with a fragrant, pale green melon. Sweltering under my required head scarf, eyeballs stinging from the pollution that smothers the city of 14 million, I’d gulp the heavy liquid down so fast it hurt.

Outside that plastic cup was a poisoned and repressed city; inside it, an ephemeral, green alpine lake whose frozen breeze cooled my face. My cousin, taking unfair advantage of my obvious delight, would often warn me that I would never get to come to Iran again, or that no one in Iran would ever serve me Ab-e-Taliban again, if I voted for Kerry. (This was kinder than some of his other political bullying, such as his threats to put me out on the street with a note pinned to my back that read “Down With the Mullahs!”)

Actually, the name of the drink wasn’t Ab-e-Taliban but Ab-e-Talabi (“Talabi melon water”), but I liked how my Iranian family laughed when I used the other name. “One is delicious, the other disgusting,” my cousin liked to say, for the Sunni Taliban of Afghanistan had long been bitter enemies of the Shiites of Iran, and partly for this reason, George W. Bush was his man. Bush, after all, had brazenly rid Iranians of not one but two adversaries: the Taliban and Saddam Hussein.

That morning after the U.S. election, I replied to my cousin that I was in no mood to joke and that I would never vote again — though of course I didn’t mean it. And as I sat at my desk I sadly recalled the many Iranians I’d met who’d expressed hope that given another term, Bush would rid them of a third enemy, the biggest of all — their own government.

“Do not take it so hard,” my cousin replied a few hours later from the basement of his three-story flat, where I knew he would be chain-smoking his delicate, brutally unfiltered cigarettes stamped “57” — for 1357, the year of the Islamic revolution on the Iranian calendar. “We have been depressed by our government for over twenty-five years.”

During my time in Iran, I had seen why this is so. Life is hard. So much is denied (though can be got, through a lively black market or with one eye trained to the back of one’s head): free speech, alcohol, mixed-sex parties, dating, extramarital lovemaking, dancing, certain types of music, satellite dishes and, for women, of course, dressing as they’d like. But lack of personal freedoms is not Iranians’ only burden. Add gross economic mismanagement, rampant corruption, relentless inflation and an unemployment rate as high as 20 percent, and what you get is an economically struggling citizenry with few of the social outlets meant to make such difficulties of life bearable.

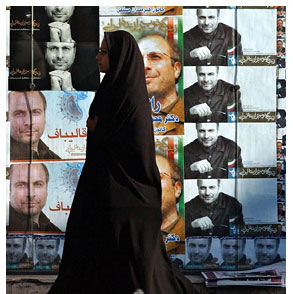

Friday it is my cousin’s turn to elect a president and try, as those blessed with even the smallest morsel of democracy do, to create a government that does not depress him. But like so many of his fellow citizens, he plans not to vote. Iranians have watched their once fabulously popular, reformist president, Mohammed Khatami, who was swept into office in an election that brought out nearly 90 percent of the population, and in whose presidency resided so many hopes of greater political and social freedoms, end his second term nearly impotent in the face of Iran’s hard-liner clerics. It is these unelected mullahs, led by Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who have the final say over the actions of all elected officials and who wield ultimate control over most institutions of government.

This time, voter turnout is expected to be as low as 30 percent. Seven candidates are in the running, with cleric Hashemi Rafsanjani, the former president and revolutionary leader, widely expected to win. Many reformists in the country have called for a voter boycott to signal rejection of the entire system of government. But those people who choose not to vote on Friday are more likely do so, like my cousin, out of sheer disillusionment and lack of hope. “Reformists, conservatives. They are all the same,” he wrote to me the other day. “It’s just a game they play to keep us busy. What is the difference between Dracula and any other vampire? They are all out to drain your blood.” And so he waits for some outside force to effect change in his country, for our president, perhaps, to choose his.

I had hoped to be in Tehran this week, to take walks and argue with my cousin. But I wasn’t able to make it. Though half Iranian, I am also the product of an American father and must apply for a visa to visit Iran. This year, for reasons unknown, I was denied that visa and access to my family, as I have been for most of my life as a result of war, politics or revolution.

So for now, but only, I hope, for now: no more Ab-e-Taliban for me, no democracy for my cousin.