Shaquille O'Neal once gave a photo to George Mikan, the NBA's first great big man and first great star, inscribed, "Without you, there would be no me." The Miami Heat star repeated the sentiment earlier this month when he publicly offered to pay for Mikan's funeral.

It doesn't appear to be a sentiment widely held by NBA players, or by the league itself. In a little over a half century the NBA has grown from a struggling entity vainly hoping to fill hockey arenas on dark nights to a $3 billion international business that turns young ballplayers into millionaires by the dozen.

Tuesday night 30 such players, the first-round picks in the draft, will find out which teams will sign them to a guaranteed, multimillion-dollar contracts. The average NBA player makes $4.9 million a year. More than 20 players make at least $13 million.

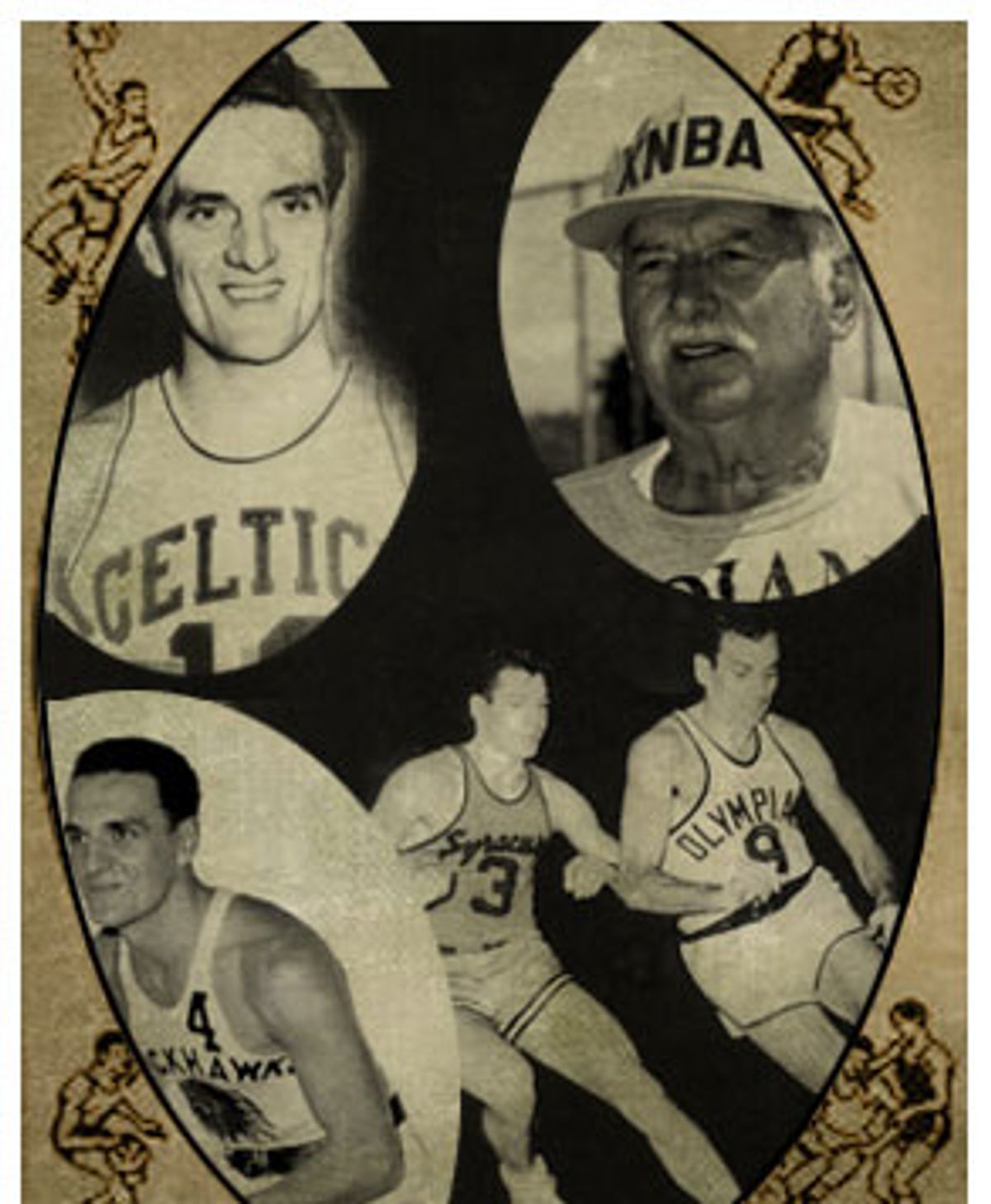

But as the finishing touches are being put on the league's new collective-bargaining agreement with the players union, some of the game's pioneers, men who played in front of small crowds for teams like the Chicago Stags and the Tri-Cities Blackhawks -- but also for the Boston Celtics and the New York Knicks -- are hoping for an increase in what they consider an ungenerous NBA pension.

Others are hoping, after two decades of fighting, to be included at all.

The former players in both groups are in their late 70s and 80s mostly, some of them doing fine and others in desperate financial straits. They see the billions being generated by the league they helped build and wonder why today's millionaires won't shake loose what amounts to chump change to help them out.

"We were responsible for starting the league and keeping it going," says John Ezersky, 83, who played in the old Basketball Association of America and then the NBA in a three-year career that ended in 1950. "I think we're entitled to a little bit."

Ezersky gets no pension, and he and his wife, Elaine, live on about $15,000 a year in Social Security. He retired five years ago after spending a half century driving cabs in New York and San Francisco.

"The league owes its very survival to these players," says Neil Isaacs, author of "Vintage NBA: The Pioneer Era (1946-1956)," a history of professional basketball's early days. "The league could not have survived unless these players played under extraordinarily difficult circumstances and kept at it for the love of the game."

What makes their fight so compelling, and the resistance of the league and the National Basketball Players Association so puzzling, is that, relatively speaking, what they're asking for is such a pittance.

Bill Tosheff, who leads a group of three- and four-year veterans who are not included in the pension plan, says $400,000 a year would take care of them all, diminishing annually as the bell tolled.

That's a little more than a third of what the San Antonio Spurs paid forward Tony Massenburg this year to sit on the bench. It's less than 1 percent of the average payroll of a single team. It's significantly less than what just two teams, the Celtics and the Toronto Raptors, donated to tsunami relief.

"They could put on four exhibition games, or one exhibition game per team, or T-shirts" to cover pensions, Tosheff says. Isaacs suggests using a fraction of the fines assessed to players over the course of a season.

"It's like we're pressing our noses against the window of a restaurant where everyone inside is just gorging themselves," says Bob Cousy, the Celtics point guard of the 1950s who is among the greatest players ever and one of the most prominent of the so-called pre-'65ers, men who played before the league's pension plan was introduced in 1965 and were thus excluded.

"They should be able to take care of everybody, not just the three- and four-year guys but even the ones who just had a cup of coffee. It wouldn't be a blip; they wouldn't feel it at all."

Or as Ezersky puts it, exaggerating a little, "My gosh, just don't go out for dinner one night and you could give me a whole year's pay."

Tosheff, a tenacious and energetic 79-year-old who was a successful general contractor in San Diego for 45 years, says that he has been able to prove the eligibility of 10 men who hadn't known they had pensions coming. "Some of them think I'm Jesus Christ, some think I'm Santy Claus, but it's just a matter of researching," he says. "The NBA won't do it, the players association won't do it, so I do it. And why aren't they doing it? Why am I finding guys and they're not?"

The 1965 collective-bargaining agreement created a pension benefit for all players from that point on who played at least three years. The payment is now $358 a month for each year played, which amounts to about $43,000 for a 10-year veteran. That could go up significantly under the new CBA.

In 1988, former Boston Celtic Gene Conley and his wife, Katie, organized a group of veterans that they called the NBA Old Timers Association, which included Hall of Famers Cousy, Mikan, Dolph Schayes and others. The association lobbied successfully to have pre-'65 players brought into the pension plan. But they came in at a lower rate, first $100 a month, since raised to $200 for 100 or so surviving veterans.

And for pre-'65ers to qualify, they had to have played at least five years, not the three that post-'65 players need.

That left out about 85 players with three or four years' experience -- "some of whom were every bit as good as the five-year veterans," says Isaacs. "It was not a good business to be in, and after four years they had to find a way to make a living."

Tosheff, who played two seasons with the Indianapolis Olympians and one with the Milwaukee Hawks before turning to minor-league baseball in 1954, has been battling to get his group of three- and four-year veterans included in the plan ever since, even going to Congress in 1998. So far, no dice.

The 85 have shrunk to 45, including four men he can't find and who might be dead. He says the league and the union, which have resisted him at every turn, are just waiting for the men he calls "my guys" to die out.

"Death cures a lot of things," he says.

While the league and the union have agreed on the new CBA, they're still negotiating the smaller details, including the pension plan.

"There's extra money being put into the pension, but they're still working out the specifics of how it's going to work," said NBA spokesman Tim Frank. Asked if it's possible the three- and four-year men would be brought into the pension plan, Frank said, "I wouldn't assume anything until they work out the details."

One thing that irritates Tosheff's group is a part of the 1988 agreement that allows pre-'65 players to get credit for a year in the league if they were in the military -- but only if their basketball career was interrupted or immediately preceded by military service.

"Most of my three- and four-year guys who are left out of the pension were in World War II," Tosheff says, "and then we went to college, and then we played in the NBA, and we don't get [credit for] military time. That is a kind of a hook in there that really bothers me a lot because we were all in the same war."

"It was a mishmosh in 1946; it was a league just starting out," says Walt Budko, 79, who returned to his studies at Columbia University after getting out of the Navy that year. He later played four years for the Baltimore Bullets and the Philadelphia Warriors. "I went back to school, graduated in 1948. I wasn't going to jeopardize my education to try out. In fact, I didn't even know they had tryouts."

Isaacs, the basketball historian, finds the military service rule ironic. "My thinking goes like this: Here's [NBA commissioner] David Stern arguing, with his 19-year-old minimum age, kids should stay in school, at least for a while," he says. "Now the guys who come out of service and go back to school, and then come into the league, are punished because they went back to school. It makes no sense."

A call to the league seeking comment from Stern or his deputy, Russ Granik, was not returned.

Tosheff says he has paperwork documenting that Cousy agreed to a secret "sweetheart deal" with Stern, in which Cousy and his fellows agreed to keep quiet, and stop lobbying publicly, in return for Stern's getting them pensions in the '88 CBA. Universally, the three- and four-year men say they knew nothing of the 1988 deal before it was announced, and many say they only began pushing for a pension after that.

Cousy says he's being given credit for power he didn't have.

"Yeah, they're mad at me," he says of Tosheff's group -- though he couldn't remember Tosheff's name offhand. "It's because they think we were sitting around the table negotiating, giving things away. It wasn't like that. The NBA said this is what we're going to do and we said, 'Thank you very much.' We were glad to get anything.

"And I have to say it wasn't brought up at the time. There was no one saying that we should have included the three- and four-year guys. I don't remember that argument being made at all. And if it was, I'd like to think positively of my guys that we'd have said something about it. But we just didn't think of it."

Cousy, meanwhile, who says he lives comfortably and plans to donate any increase in his own pension to needy former players, is unimpressed by O'Neal's gesture of paying for Mikan's funeral, calling it a P.R. stunt, though he says he liked O'Neal when he met him while making the movie "Blue Chips" in 1994.

"I'm 76 years old, and I guess when you get a little older you get cynical," he says. "If you" -- meaning Shaq -- "really want to help the old guys, why don't you put in a call to [union chief] Billy Hunter, who'll return your phone calls, and tell him, 'We should do something for them.'"

The players association didn't return a call seeking comment, and O'Neal couldn't be reached.

One issue that can't be avoided when looking at the NBA of today and the league in its early days is race. Most current NBA players are black. In the '50s, the league was overwhelmingly white. Could it be that today's black players are withholding help from their elders as a sort of payback for long-ago racism? Isaacs, the historian, doesn't think so.

"Maybe there are some current black players who think, 'Oh, well, they don't deserve anything.' I wouldn't deny that there may be some," he says. "I think there are just as many, especially those who take an interest in the history of the game, who would not buy in to that."

The more likely, more widespread problem is that not many active players take an interest in the history of the game.

"We were like that too," Cousy says. "When you're a professional athlete you're so wrapped up in what's going on around you, you just don't have time for anything else."

And so it goes. The NBA cash register rings and the men who helped build the league fight it and the union and at times one another for a small share.

"The two things we have left, probably," Tosheff says, "one is our faith, if we've got one, and number two our memories. And if our memories are not good ones, like being in the NBA, then we have a hard time sustaining the rest of our life."

Some of the excluded players are interested only in the principle of the thing. "I make no bones about it: I'm fortunate that I don't need their goddamn money," says Budko, who had a long and successful career in the insurance business and now lives in a retirement community in the Baltimore, Md., suburb of Timonium.

"But that still doesn't take away from the fact that there are fellows that are benefiting that in many ways my credentials far outdo whatever they did to contribute to the success of the league."

Others don't just want the money, they need it.

"I'm financially destroyed. I haven't got any money at all," says Ezersky, who lives with his wife in a condo in Walnut Creek, Calif., that a grandniece and her husband bought for them to live in. They pay their relatives a reduced rent.

Ezersky says he has only "the stupid head on my shoulders" to blame for not planning for his own future, and he doesn't begrudge current players their success. "I have no bad feelings. Hey, gosh, I wish them all the luck in the world. God bless 'em, we should all make $10 million a year," he says.

But he helped create the world those players live in, and, he says, "a little tiny bit would help quite a bit. Some of the guys don't need it, but some of us really do.

"I keep getting all these letters from the NBA and the players association. All the big affairs. How many rooms would I like? I always write back, 'How many rooms can I get for $1,265 a month in Social Security?' I always put that down. 'Thanks for the help.' I get no response."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Shares