Steven Spielberg's "War of the Worlds" is the ugliest little movie of the summer. Extravagant in movie terms but stingy in emotional ones, it embodies all of Spielberg's bad impulses and almost none of his good ones: It's a grand display of how well he knows how to work us over, and yet the desperation with which he tries to get to us is repulsive.

Spielberg knows what we're expecting when we come out to see "War of the Worlds": a scary picture about an alien invasion, based on a 107-year-old novel by H.G. Wells and featuring one of the world's biggest (and dullest) movie stars. But he also needs to show us how savvy he is about our national mood -- that's part of his little pied piper's song and dance. At one point the camera scans a wall covered with fliers of missing loved ones (presumably humans who have been abducted or just plain disintegrated by the marauding aliens), as direct a reference to post-9/11 New York City as you could make. I can't possibly divine what Spielberg intends by that shot. Are we meant to nod solemnly, jolted by the recognition that this alleged bit of summer fun has a real-life parallel? Is he trying to make us feel guilty for enjoying the jolts and thrills he's obviously working so hard to give us? Or is he just a really cheap, shallow guy? It's bad enough that Spielberg has lost faith in his own sense of decency, but it's even worse that he's lost faith in the decency of his audience.

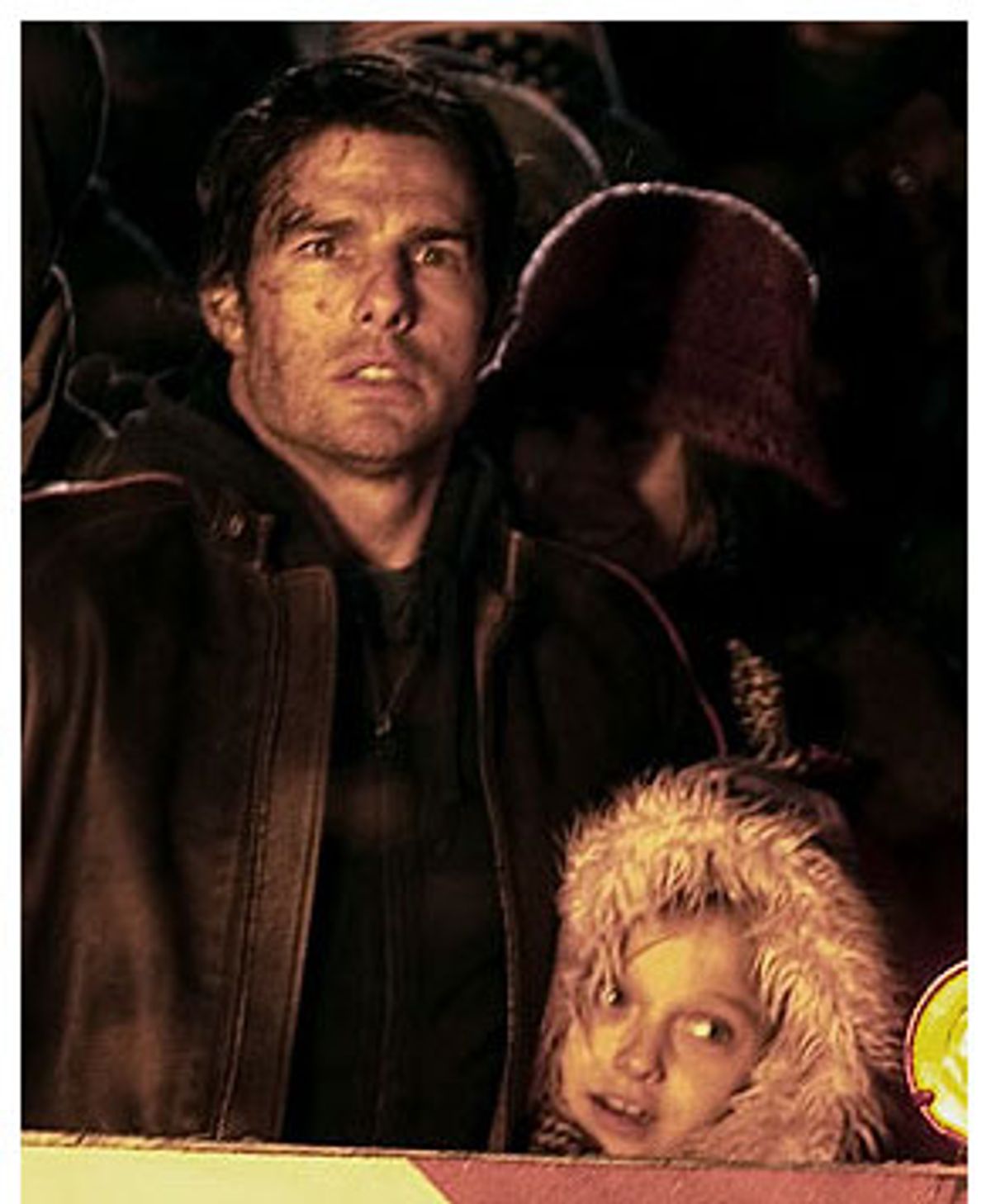

"War of the Worlds" is a delusional work of craftsmanship -- it's all visuals with no vision. Cruise plays Ray, a divorced dockworker who doesn't have the greatest relationship with his kids, 10-ish Rachel (Dakota Fanning) and teenager Robbie (Justin Chatwin). Shortly after his ex-wife (Miranda Otto), now remarried and pregnant, drops those kids off at his modest, messy New Jersey house for the weekend, a weird lightning storm changes the color of the sky and the fate of the world. Ray goes into the center of town to find out what's happening, and, along with a crowd of fellow citizens, watches in horror as a massive metallic "creature," poised on three spindly legs, breaks up through the concrete and begins zapping buildings and humans, willy-nilly. These so-called tripods are really vehicles of some sort, with moist, skinny aliens inside: They've been planning this attack for millions of years and they waste no time getting down to business, not just in New Jersey but in locales all across the globe.

All good horror and sci-fi movies build a sense of dread: We get that sickly feeling in the pit of our stomach as we begin to realize that evil is creeping our way -- it's the body's way of dropping anchor against runaway flights of the imagination. But Spielberg doesn't just build dread; he pimps it. The picture is dark and dank-spirited (a quality that many moviegoers often mistake for complexity, as if all shades of darkness were created equal).

The "tripods" themselves, at least when we first see them, are magnificent and imposing -- they've got shiny, sleek wedge-shaped heads, and their sinister determination is weirdly graceful as they amble forward on those supermodel daddy long legs. But there's grim glee in the way Spielberg shows us the horrors that these creature vehicles wreak: When their deadly rays hit human flesh, skin, bones and tissue disintegrate immediately, although the shell of clothing around them remains intact -- pants and shirts flutter helplessly, still airborne even though the terrified, running bodies inside have already turned to ash. (Later in the picture, this image will be reused: The ghostly picture of bodyless clothing drifting from the sky is unnervingly, and obviously intentionally, reminiscent of the melancholy flutter of debris that inhabitants of lower Manhattan and parts of Brooklyn remember from the morning of 9/11.)

Dakota Fanning's knowing-but-innocent face comes in handy for Spielberg, over and over again. More often than I could count, Spielberg would move the camera in on her terrified face, as if he were expecting us to get our jollies from fixating on the fears of a child. He mercifully spares us from seeing major world landmarks destroyed, although the generic horrors he puts in their place serve the same purpose anyway: We see a church facade crumbling to the ground (though not before the sunlight streams through its central stained-glass window), and a crashed plane split into numerous clumsy parts, although, conveniently, there are no bloodied bodies (presumably, the aliens have already sucked them out). Later, the aliens cast a web of blood-engorged vines over everything in sight; we see crows pecking greedily at these throbbing red streaks. Spielberg presents all of these horrors not with a sense of fun, or even an over-serious sheen of import, but with a self-satisfied smirk. Each succeeding image reads like a boast: How does that grab ya, kids?

There's plenty more, most notably a weird interlude in which Tim Robbins appears as a deranged freedom fighter who thinks he's going to get the better of the aliens via a surprise shotgun attack. (This scene also includes a bizarre exchange between Robbins and Fanning notable for its not-so-subtle child-molester vibe.) And did I mention the sequence in which a crazed, terrified guy claws through a broken windshield with his bare hands?

Obviously, all of these incidents and images are serving some greater purpose in Spielberg's mind, if not actually on the screen. Just as it has been decreed, ad nauseam, that all '50s sci-fi movies are actually about the fear of communism, Spielberg's "War of the Worlds" must certainly be about our fear of terrorism. In a recent Reuters article, Spielberg himself said the movie is "certainly about Americans fleeing for their lives, being attacked for no reason, having no idea why they are being attacked and who is attacking them."

But in addition to all that heavy-handed symbolism, there's a sadistic, mean-spirited vapor hovering around "War of the Worlds." I suspect Spielberg wants to cover all the bases: "War of the Worlds" can be a political movie for those who want to see it as such, and a mindless entertainment for everyone else. But no matter how dazzling or advanced its special effects are, it's far less sophisticated than Byron Haskin and George Pal's 1953 version of the same material.

That "War of the Worlds" is usually treated as a parable of Cold War fears, but I think that's the laziest reading of the picture. Haskin is more interested in human nature than he is in politics -- specifically, the possibility that human beings are their own worst enemies. But he also recognizes that we can overcome our worst impulses. Spielberg shows a similar distrust of humankind, specifically in a scene in which throngs of zombielike citizens, driven mad by their own fear, descend upon the car (the only working vehicle around) that Ray has managed to get a hold of. (A few of them dive into it headfirst through a back window, as Fanning screams in terror.) But compare that blinking neon message-moment with one brief shot that Haskin gives us: A child pilfers from an upturned ice-cream cart as the camera pans slowly to a hungry dog lapping up some of the melted contents -- an image that blurs innocence and savagery in a way that no scrap of footage in this modern "War of the Worlds" comes close to.

And in the midst of all this, where is Tom Cruise? Cruise, who has recently gotten so much attention for his love life, his wacko spiritual beliefs and his Oprah antics, is barely a presence in this monstrosity of a movie. The picture's recurring question, underlined repeatedly by the way Cruise screws up his face in an expression of extreme concentration, is, "How far will we go to protect our children?" That's supposed to be a deep, philosophical question, but it's actually a fairly hollow one. (Most people who have kids already know they'd go pretty far; and plenty of people without kids would go pretty far to protect other people's kids, too.)

At one point, just after Cruise has witnessed the first incident of alien-invasion horror, he stares at his reflection in the bathroom mirror, trying to get a handle on what he's just seen, and on the man he has now become. Wild-eyed, he scrutinizes his dusty, terrified visage. He's acting so hard the bones nearly pop out of his skin. It's not a good scene, but it's the only one in the picture where we get a gut sense that human lives are at stake. The rest of "War of the Worlds" is just smoke, mirrors and a once-great filmmaker's assumption that it's OK to mine real-life tragedy for the sake of movie magic. Welcome to blockbuster hell.

Shares