The light of the West Texas sky streams through big plate-glass windows and illuminates Jason Willaford and his wife, Rea, sipping freshly ground coffee in the Marfa Book Co. The slim and attractive couple, who met in Los Angeles, moved to Marfa last summer to open Galleri Urbane, a boutique specializing, like so much of the town, in contemporary art. So far, their experience has been wonderful. "Marfa's a lot more sophisticated than most places," Willaford says. "When someone here sets out to do something, they do it nice. That's why people like it here -- no Wal-Marts."

When Tony Trento imagines Marfa, his voice, thickly upholstered with his native Long Island, N.Y., accent, grows excited. "Marfa needs more retail stores and affordable houses," says the developer, who owns the American Plume and Fancy Feather Co., based in Marfa, which crafts boas and masks from turkey feathers and sells them to exotic dancers and Las Vegas showgirls. "There could be a truck stop, a McDonald's, or maybe," he says, contemplating something truly special, "a Wal-Mart."

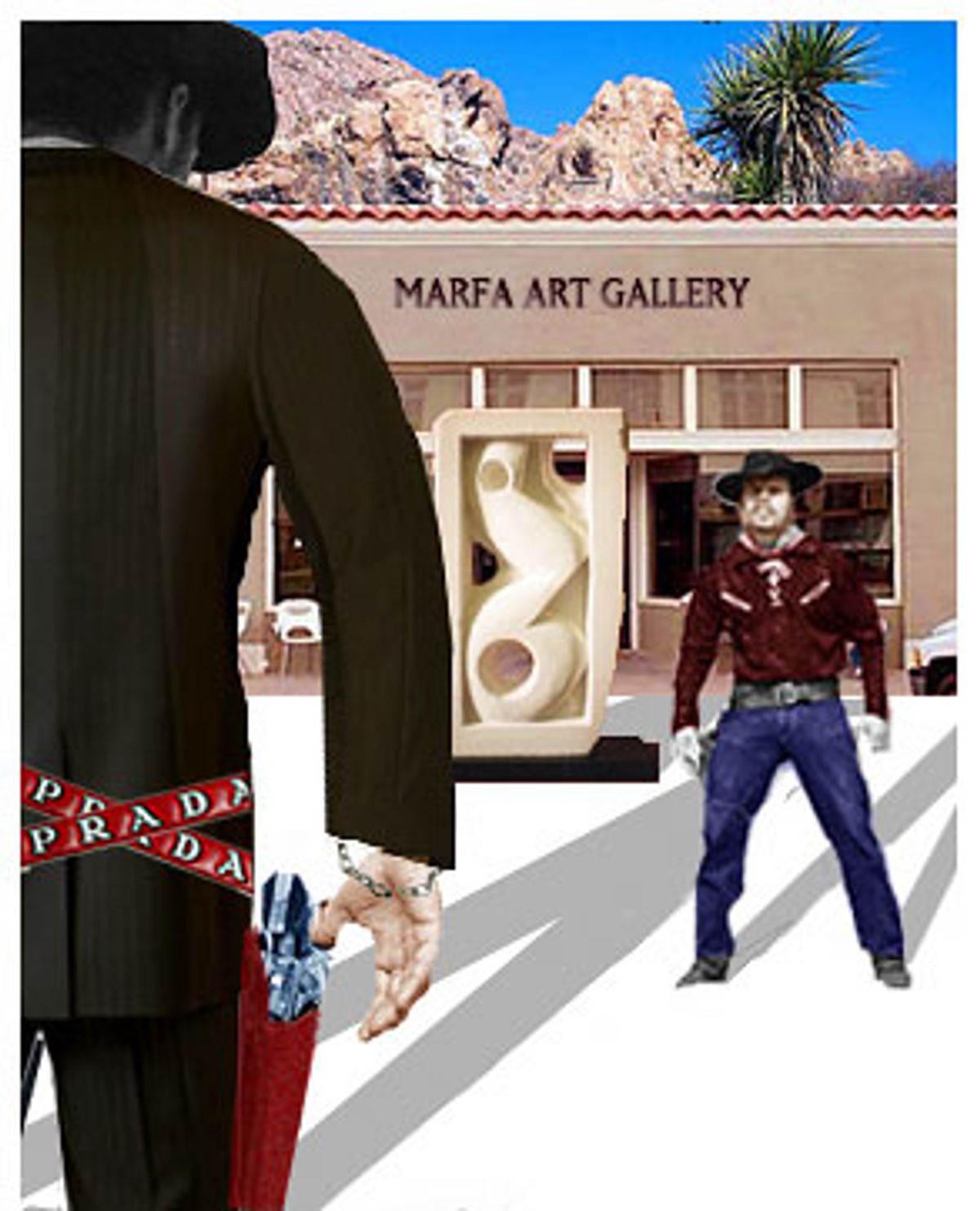

A classic Western showdown has come to the hottest little town in the country. Set amid the cedar-shaded, yucca-dotted lands of West Texas, surrounded by grasslands as wide as the Serengeti, Marfa may be the last un-Starbucked place in America. In the past few years, a covey of A-list artists, corporate players and real estate speculators have descended on the tiny town (pop. 2,121). Enchanted by its spare beauty -- think "The Last Picture Show" with a Christian Liagre makeover -- they're also drawn by elite cultural institutions like the Chinati Foundation, dedicated to hip installation art, and the Lannan Foundation, a prestigious literary organization.

Trailing in the trendsetters' wake has been the national media. Marfa's press clips glow like newly lit luminaria. Publications such as Vanity Fair, Elle and ArtForum venerate Marfa's Victorian ranch houses and Texas Territorial adobes, the burgeoning art scene and its rich patrons. The movie "Giant" was filmed in Marfa 50 years ago, when its stars James Dean, Elizabeth Taylor and Rock Hudson could be seen kicking around town. These days, the scene makers include Dan Rather, Frances McDormand, Dwight Yoakam and Tommy Lee Jones. A National Public Radio station is coming. The real estate madness already has. Four years ago, Marfa adobes were selling for $40,000. They're now $200,000 and no doubt a good deal higher after the recent New York Times story, "The Great Marfa Land Boom."

It's a familiar pattern. Western havens like Aspen, Colo., Taos, N.M., and Missoula, Mont., were Marfas once, playgrounds for coast-hugging hipsters who could slip into jeans and the rustic camaraderie of the outback. But those towns are full up now, victims of their popularity. Now the sagebrush Medici come to Texas, piloting the corporate Gulfstream into tiny Marfa Municipal airport and bellying up to the jes-folks atmosphere of Joe's Bar, where the Bud Light costs $1.75. The town remains an aesthete's dream, devoid of Olive Gardens, Best Buys and any sign of the suburban middle class. Rather, Marfa is the honest texture of adobe and fine art set against a big sky. It's the simplicity of line and the haunting emptiness of the land.

But this isn't what Marfa means to everybody in Presidio County. Most residents don't own much in this southwest corner of George Bush's Ownership Society. The county is 84 percent Mexican-American; 36 percent of its residents live below the poverty line (the U.S. average is 12 percent). Marfa itself is 70 percent Hispanic.

Today, on Marfa's main street, tony art galleries and wine shops are driving away traditional cafes and shops, whose local owners can't afford the new sky-high rents. Everywhere you go the townsfolk, independent Texans to the core, lament the changes to their community. The term "ChiNazi" is used locally to describe anyone from out of town who arrives with artistic ambitions and a superior attitude. Observes one local cattle rancher, who asked to remain anonymous: "We're filling up with triple A's -- artists, assholes and attorneys."

Some of the new businesses hire people who were born and bred in Marfa, and that helps the local economy. At the same time, the cost of living is rising above their means, and they welcome Trento's plan for big-box retail and ranchettes. To them, a steady job and an affordable home near extended families are more enticing than living in little Bauhaus on the prairie.

The ever-widening chasm between social classes in America has reached West Texas, with acrimony erupting all around. Trento's plan threatens Marfa's art community, spearheaded by the Chinati Foundation, which is determined to prevent the ambitious developer from besmirching its views. The tussle between subdivisions and sightlines stirs up questions to make the culturati squirm in their Eameses. Are the aesthetic desires of an elite more important than the economic needs of the majority? Will Marfa be a town where working-class residents can thrive or will it become Marfa's Vineyard, a weekend sandbox for people whose tastes veer more toward pinot noir than Dairy Queen? Are big-box retail jobs less desirable than "All Things Considered"? Should you sell a Frenchman your adobe? What price arugula? Marfa is about to find out.

Marfa has always entertained great notions. Founded in 1883, it was named by an engineer's wife after a servant in "The Brothers Karamazov." She read the Dostoevski novel while waiting for her husband to finish working on the Southern Pacific railroad. Soon enough, the town grew rich on ranching. In the 1930s and '40s, cattle barons attended elaborate balls and afternoon teas at the Hotel Paisano, an ornate, stuccoed affair that still stands and looks like a bit of Old Seville marooned west of the Pecos.

After World War II, Marfa was in trouble, its robust population having dwindled with the shuttering of its military bases. In 1971, the isolated town was just the place that hard-living Manhattan sculptor Donald Judd was looking for. He wanted a big backyard for his large works and here it was. A fractious and ornery character, Judd cottoned immediately to Marfa's seclusion and affordability. With help from the Dia Foundation, a New York-based cultural organization founded by German art dealer Heiner Friedrich and his wife, Houston oil heiress Philippa de Menil, Judd began acquiring Marfa real estate for his installations. After a falling-out in 1986, the partners reached an out-of-court settlement that created the Chinati Foundation. Judd oversaw the foundation until he died of lymphoma in 1994.

Minimalism wowed the contemporary art scene in the '70s, and because Judd was a giant in the movement, he drew disciples from all over the globe to West Texas. As minimalism increased in popularity, so did Judd's mecca. Many of the pilgrims today evoke religious metaphors for the stark beauty of his work and its setting in wild Texas. A bumper sticker seen around Marfa sports the acronym "WWDJD?" (What Would Donald Judd Do?)

Visit Chinati and you can see why Trento's planned subdivision is as welcome as a belch during a church service. Located in the low-slung barracks and Quonset huts of the former Fort Russell, the foundation and its spare, wind-swept grounds seem more monastery than museum. Buildings on Trento's property, just south of the foundation, would obstruct the sightlines.

Today, articulate docents lead art lovers on a four-hour tour of installations created specifically for the site by world-famous artists such as Claes Oldenburg, Dan Flavin and Ilya Kabakov. The foundation's prized pieces are 100 milled aluminum cubes and giant concrete rectangles made by Judd. These are dusted regularly by the resident interns, usually MFA candidates from Ivy League universities.

Chinati public affairs coordinator Nick Terry credits Chinati with Marfa's renaissance. "Over the past 10 years, the Chinati Foundation has revitalized Marfa, has activated the economy and the town's cultural life through manifold new initiatives," he says. "It has attracted new residents who contribute to the well-being of the region."

The foundation does try to be a good neighbor. In 2000, it lent the city storage space when Marfa was renovating its Victorian-era courthouse. Each year, Chinati waives its $10 entrance fee and invites the townspeople to its grounds to view works such as Tony Feher's piece of basalt atop a plastic Tupperware-like container, 75 of which were given to Chinati donors.

In January this year, according to Jack Strain, who oversees American Plume and Fancy Feather Co., Chinati director Marianne Stockebrand "asked in an offhand manner if we were interested in selling to Chinati because they are very much against development south of their property." Strain named a price, which he won't reveal, but Stockebrand didn't bite. "I never did think they were serious about making an offer that would reflect the value," he says. "He was asking a very high price that we couldn't afford," is all Terry will say.

Following the January meeting, Stockebrand embarked on a campaign to stop American Plume from developing its property. On March 7, she wrote a letter to Marfa's then mayor, Oscar Martinez, and Presidio County Judge Jerry Agan, expressing her concern about American Plume's plans and their impact on Chinati's views. Trento's development "will greatly impact Chinati in its unencumbered vistas of 30 or more miles, its contemplative setting, and its natural wildlife," she charged. To save the views, she raised some very high brows indeed, enlisting blue-chip museum directors and artist Oldenburg in a letter-writing campaign to force Marfa politicians to pluck American Plume's plans before they sprout.

Martinez was unmoved, stating his first concerns were for the year-round residents and their needs. "Perhaps the near future will bring us a pharmacy, a dental clinic, dry cleaning and laundry services," he responded in a letter to Michael Govan, director of the Dia Foundation, which supported Chinati. Judge Agan was also unmoved. "The letter they wrote us said they are all for the little people," he says. "Just not in their backyard."

Escaped feathers dance across the land surrounding the American Plume and Fancy Feather building. The company arrived in Marfa 13 years ago, when Trento, who currently runs the 83-year-old family business from Pennsylvania, discovered that Marfa's arid climate made it a perfect place to dry turkey feathers.

Times are both good and bad for the company. Despite an uptick in business following a 9/11 slump, explains Strain, Trento's son-in-law, American Plume is feeling the heat from Chinese competition. But thanks to Chinati's helping popularize Marfa as a destination, the land beneath the factory has appreciated in value, an irony the art foundation probably doesn't appreciate. In response to rising land prices, Strain and Trento plan to develop the property to boost their bottom line. On the drafting board are plans to subsidize the land into retail stores, 10-acre ranchettes, and a U.S. Border Patrol station.

Trento promises to build up to 20 affordable homes, priced from $40,000 to $60,000 -- far cheaper than the antique adobes in town. "The artists and the Chinati people have driven up the costs, scaring the town's residents," he says. "I want to make it so the kids that grew up in town and want to stay in Marfa have got a place to go. Marfa doesn't have much except for the scenery, its history and the open spaces." The inexpensive homes will be tract housing, but, he is quick to add, built in a handsome ranch style. "Not like the trailer I lived in when I first came to Marfa," he says.

Many residents welcome Trento's plan, even newcomers like AmeriCorps volunteer Emily Mahoney, who moved to Marfa last year to help develop regional social services. Finding a place to live proved difficult. "I'm pretty low-income and nothing in town was manageable as far as houses go," she says. "Marfa is becoming an increasingly difficult town in which to survive, especially if you have a family."

"I hope Trento sticks to it and achieves what he wants to do," says Presidio County tax appraiser Irma Salgado. "If not for us, then for our kids. They go to school, graduate, go to college and don't come back. One reason they don't stay is because there are no places like Wal-Mart here." Live 160 miles from a big supermarket or drugstore and Wal-Mart isn't viewed as the Beast of Bentonville. Instead it's seen as a symbol of prosperity, job opportunities and, above all, convenience. "Out here, Wal-Mart stands for everything you can't usually get in Marfa," Mahoney says.

American Plume employs 13 local women, mostly Mexican-American, to create its boas. They are proud of their work. Posters and newspaper articles hang in the factory's hallways. Their boas have graced Big Bird as well as coiled around Sandra Bullock in "Miss Congeniality 2."

Sarah Villa, general manager for American Plume, supervises the artisans, who put the finishing touches on work produced in a sister factory located 58 miles south in the border town of Ojinaga, Mexico. Villa watches as Bertha Gradeja carefully steams, combs and fluffs blue ostrich plumes, readying them for a headdress that'll dazzle them in Vegas. Above them, hundreds of brightly colored boas dangle from the rafters.

"We're making art here, too," Villa says. "These ladies are very talented. They've been here since we've been here," she says of her crew. "They're dedicated and hardworking and more like a family." She shakes her head over the Chinati Foundation's refusal to welcome more development. "I'm a lifelong resident of Marfa. All I want for Marfa is for it to thrive. We welcomed Chinati when they arrived. I don't understand why Chinati doesn't want Marfa to grow."

Marfa's growing reputation as an Aspen in the making is attracting the very rich -- not just cash-poor artists and writers -- who are giving the town its extreme makeover. The biggest threat to Marfa may not be Chinati or Trento but the town's incipient fabulousness. How else to describe the Prada jacket cuddling Rainer Judd's shoulders on a recent cover of Brilliant magazine? The Texas monthly specializing in debutantes, society party pix and lavish interior design devoted an entire issue last October to Marfa. To corral its rising buzz, the magazine trundled out two SUVs from Austin stuffed to the roll bars with photographers, stylists and fashion writers. They liked what they found. "Marfa Matters," announced its cover. Yes, but to whom?

Rainer's $34,500 little black number is $9,000 more than the average Marfa family sees in a year. Clearly the magazine wasn't directed at them. Rather it was focused on the fashionable moths Marfa's flame now attracts. Air-kiss arbiters Vogue and W have both profiled the Marfa Ballroom, a new arts organization, and its owners: two young Texas heiresses, Fairfax Dorn and Virginia Lebermann.

A more accessible cultural watering hole than Chinati, the Ballroom, housed in a former Mexican dance hall, opened in 2003 with a splash. The Ballroom maintains its independent cultural streak. It has screened Kurosawa retrospectives, hosted a performance artist named Lederhosen Lucil and various national DJs, and invited "Pink Flamingos" director John Waters to lecture in a packed theater for a Wild West evening that evoked the one in 1882 when Oscar Wilde visited Leadville, Colo.

Marfa's popularity also means economic opportunity for those who understand the outlanders' tastes. New restaurants like Maiya's and the Brown Recluse have opened to serve them, and since Marfa is far from the nearest big airport in El Paso, the Hotel Paisano and the midcentury modern Thunderbird Motel, run by Austin hotelier Liz Lambert, mean the minimalist art pilgrims' progress will be a comfortable one.

Some residents, meanwhile, feel community life has taken a giant step backward. And not just because they feel segregated from the artists. Seeing their town revitalized along the lines of Dwell magazine leaves them cold. "It's about all the new things going on here -- art galleries and things like that," says a rancher whose family has raised cattle in Marfa for generations. "Newcomers would be better off in local people's eyes if they did more that involved local people. Right now, you see them in the grocery store and eating together. But they're not putting in businesses or restaurants that most locals will go to. They've come to Marfa because of the quaintness, yet they're trying to change it, to citify it. Like the bookstore. It's doing very well, and so is the wine bar, but is that something that is natural to the area of Marfa? They've redone the Thunderbird Motel, and that's great, but is it doing much for Presidio County?"

It is for some Marfa residents, like Zane McWilliams, who's worked on local ranches, and recently landed a job as a barista at the Brown Recluse. "The Marfa boom's good if you can get a job from it," he says. "If I wasn't here at the Brown Recluse, I'd be digging ditches."

It's unlikely, though, that many locals could afford to buy a new home in town. "Houses worth $20,000 or $30,000 are selling for $250,000," says Presidio County appraiser Salgado. "Adobes worth $20,000 are going for $200,000." Like thirsty cattle who can smell water miles away, lowing investors are stampeding up Highway 90 eager to buy anything with daubed mud and a screen door. Their frenzy astonishes many locals.

"People call in and ask to get in on the ground floor," observes Marfa real estate agent Linda Jenkins. "I tell them they're six years too late." Still, the inquiries keep coming. From New York. From Dublin. From Singapore. Even the French, who are making Marfa the new Paris, Texas. "I've sold four properties to French clients," says Wright. "Guess they like the art."

Some longtime residents benefit from an increase in property prices, but they are burdened by them, too. "If [the real estate boom] doesn't stop, it will be so hard for the average taxpayer who has lived here forever to pay their taxes," says Salgado. "I have to explain to them that because Mr. Smith from Houston bought a house like yours I have to charge the same rate. They ask me, 'What have I done?' and I have to tell them, 'Nothing, it's just the market.'"

The glamour carries another price tag invisible to the tourists tripping in from St. Germain or Williamsburg. The new eateries and bamboo-floored galleries have meant the end of more prosaic retailers. There wasn't much to begin with, but what's left is going fast. In February, Mary Arrieta lost the main street location for her store Ave Maria, which sold the town its religious icons, wedding crystal, and greeting cards. At the time, she paid $300 in rent. The new owner needed the Highland Street space for upscale lofts. Mike's, the local cafe, had to move off Highland, too.

"For 29 years, I could afford to rent on [Highland]. Now I can't," says Arrieta. "It is sad the way the art crowd is working it out so that they don't have to lift a finger to put us out. Mike's Cafe was the only one left and he's going to be out by July. Marfa Cable [TV] is looking for a place. They say to me, 'Mary, where are we going to go?' We cannot buy socks or pants here. The other people are rich. They jump in their planes, fly to the city and buy what they need."

In the showdown between minimalism and big-box retail, there's no truce in sight. "I guess the feather company feels Chinati is snotty and Chinati feels threatened," says newly elected Marfa Mayor David Lanman, a transplanted Boston craftsman. Despite its protests, Chinati's campaign seems doomed. As Judge Agan points out, Trento's land is in unincorporated Presidio County. "He can build skyscrapers if he wants to," Agan says. "As long as he has a permit, there's nothing we can do." Currently, Trento is waiting to hear whether his subdivision will be home to a new U.S. Border Patrol station. He's in competition with another Marfa site and should know by fall. In the meantime, he continues to refine his blueprint for ranchettes and retail stores.

Lanman says the last thing he wants is to see Marfa become another Santa Fe. "When a town becomes a product and not a vision you lose something," he says. He points to a "Third Way," recognizing that Marfa must grow but in the process not ruin what is special about the town. "We're trying to develop guidelines for Marfa to encourage or limit the size of buildings in particular areas," he says. "People will have to apply for permits now -- they won't just be granted one over the counter [automatically]." (This won't affect Trento's development, as it's outside city limits.) Lanman hopes that new ideas, what he calls "frontier vision," will encourage townspeople to find solutions to how Marfa should grow. As an example that benefits everyone in town, he points to a new nonprofit health clinic, Marfa Health and Wellness, run by Kate Wanstrom, a local nurse practitioner, which opens this fall in an old Baptist church behind the Thunderbird Motel.

For now, though, the Marfa boom shows no signs of flagging. In fact, it is reverberating around the Texas big bend to Alpine, Fort Davis and Marathon. Each town is developing its own unique flavor. Austin politicos, such as columnist Molly Ivins, favor Marathon. (There's a boutique there called AUSTINTaTIOUS.) Fort Davis draws affluent retirees, especially from the Houston area. Alpine, the region's commercial hub and site of Sul Ross State University, attracts people from as far away as Germany.

For the next round of urban refugees, worried they're too late to cash in on Marfa's zeitgeist, fear not. The Texas Historical Commission, a state agency for historic preservation, says Alpine, the town next to Marfa, has the largest collection of historic adobe structures outside of El Paso. Drive to Alpine's south side. There, on Gallego Avenue, across from Our Lady of Peace, the pretty Catholic Church fashioned from native stone, sits an old adobe. A hand-lettered sign is affixed in front: "For Sale -- $25,000 -- Price Firm." Or said. It's recently been removed.

Shares