Almost every significant aspect of the investigation to bring the London terrorists to justice is the opposite of Bush's "war on terrorism." From the leading role of Scotland Yard to its close cooperation with police, the British effort is at odds with the U.S. operation directed by the Pentagon.

Just months before the London bombings, British counterterrorism officials were startled upon visiting the Guantánamo prison that they did not meet with legal authorities but only with military personnel; they were also disturbed to learn that the information they had gathered from the CIA was unknown to the FBI counterterrorism team and that the British were the only channel between the two U.S. agencies. The British discovered that the New York City Police Department's counterterrorism unit is more synchronized with their methods and aims than is the U.S. government.

The Italian counterterrorism operation that was essential in the capture of one of the alleged terrorists fleeing from London is itself in open conflict with President Bush's "war." Last month, an Italian prosecutor filed indictments against 13 CIA operatives who allegedly betrayed their Italian intelligence colleagues in surveillance of an Egyptian Muslim cleric, by using their information but not telling them about the "rendering" (that is, kidnapping) of the suspect to Egypt rather than permit his arrest in Italy. Now the CIA agents are fugitives from Italian justice.

International counterterrorism is running afoul of Bush's imperatives for what has become a "dirty war." Although Bush's "war on terrorism" is a phrase his administration last month declared was obsolete (only to have Bush reimpose the slogan Wednesday), the dirty war remains very much in place.

Since Sept. 11, 2001, Bush has proposed a sharp dichotomy between "war" and "law enforcement." In his 2004 State of the Union address, he ridiculed those who view counterterrorism as other than his conception of war: "I know that some people question if America is really in a war at all. They view terrorism more as a crime, a problem to be solved mainly with law enforcement and indictments ... The terrorists and their supporters declared war on the United States, and war is what they got." During the 2004 presidential campaign, Vice President Dick Cheney contemptuously criticized the application of law enforcement as effeminate "sensitivity." In June of this year, Bush's deputy chief of staff, Karl Rove, attacked the very idea of "indictments" as a symptom of liberal weakness.

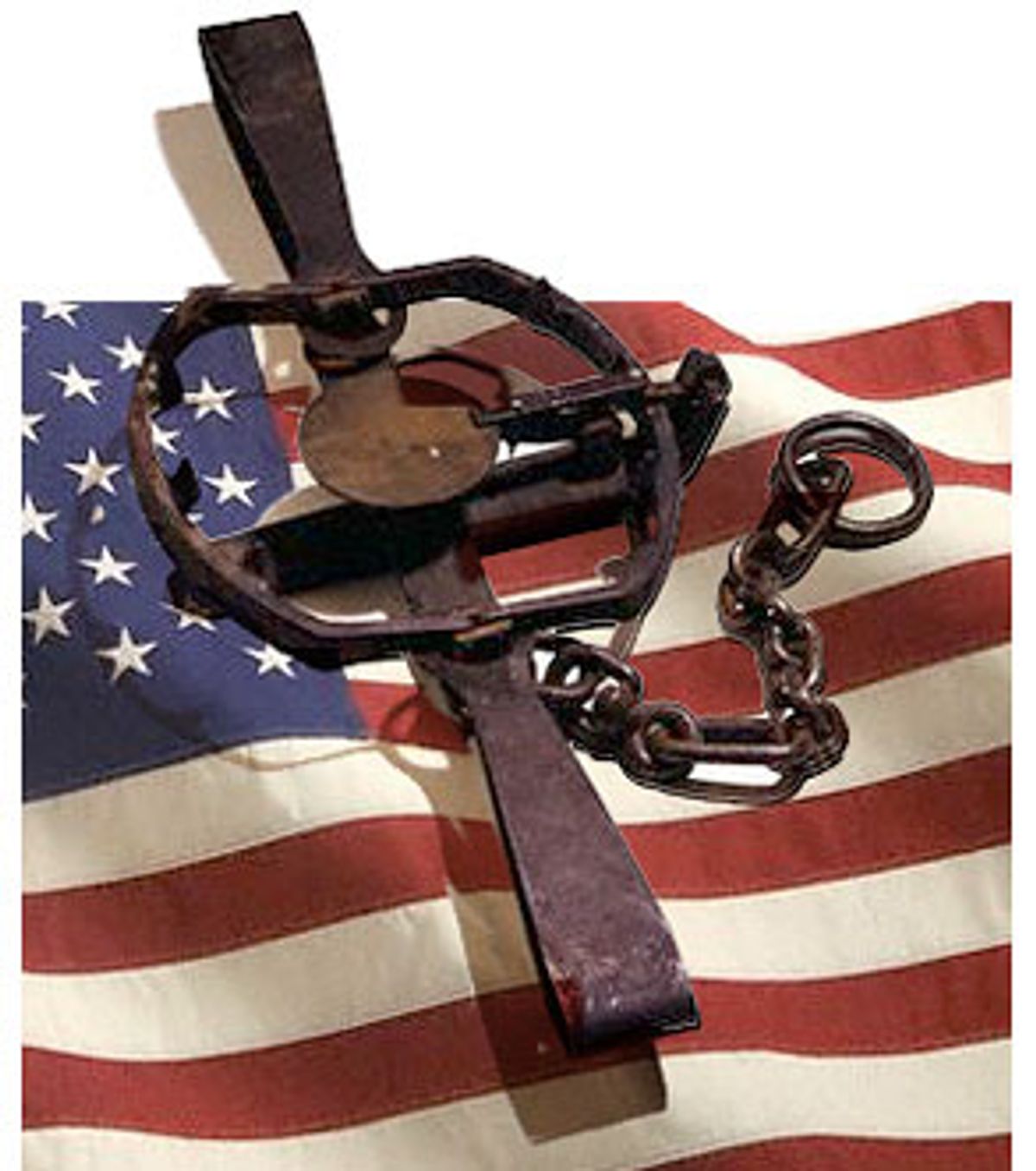

Against the strongest possible internal opposition from senior U.S. military officials, the military's corps of lawyers, former Secretary of State Colin Powell and the FBI, Bush disdained the Geneva Conventions and avoided legalities, especially trials, to pursue a policy of torture. He created a far-flung system of prisons run by an unaccountable military chain of command apart from traditional counterintelligence. It has been operated clandestinely, removed from the oversight of Congress. And Bush has fought in the courts against the intrusions of due process to retain supreme presidential prerogative.

Yet Bush is increasingly embattled in defense of his dirty war. The Pentagon has appealed a federal judge's ruling to make public 87 photographs and four videos from Abu Ghraib depicting "rape and murder," according to a senator who has seen them. Meanwhile, the Pentagon has quashed the recommendation of military investigators looking into FBI reports of torture at Guantánamo that its former commander, Maj. Gen. Geoffrey Miller, be reprimanded for dereliction of duty.

Last month, three top military attorneys from the Judge Advocate General Corps for the Army, Air Force and Marines testified before the Senate that they had objected from the start to the new abusive techniques of interrogation of prisoners. One memo revealed by Maj. Gen. Jack Rives, deputy judge advocate general of the Air Force, said, "Several of the more extreme interrogation techniques, on their face, amount to violations of domestic criminal law."

In response, three Republican senators -- Lindsey Graham, John McCain and John Warner -- have proposed legislation that would in effect abolish Bush's dirty war. Their bill would prohibit "cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment" of detainees, hiding prisoners from the Red Cross and using methods not authorized by the Army field manual. One of these senators, McCain, himself a prisoner of war in Vietnam, released a letter signed by more than a dozen retired senior military generals and admirals as well as prisoners of war: "The abuse of prisoners hurts America's cause in the war on terror, endangers U.S. service members who might be captured by the enemy, and is anathema to the values Americans have held dear for generations."

Cheney interceded to attempt to force the senators to withdraw their bill, claiming they are hurting the "war on terrorism," but they have refused. McCain declared that the debate is not about the terrorists: "It's not about who they are. It's about who we are."

But the dirty war that damages the difficult work of counterterrorism continues unabated. It goes on for reasons beyond domestic political consumption. At its heart lies the drive for concentrated executive power above the rule of law.

Predictably, Bush's dirty war is having a counterproductive effect, just as dirty wars did in Vietnam, Algeria and Argentina. For every militant abused or killed, a community of like-minded militants is inspired. Hatred, resentment and vengeance are the natural outcomes. There has never been a victory through a dirty war over these forces. To the extent Britain responds with the assertion of the rule of law, it serves as a notable counterexample to Bush's dirty war.

Shares