As Todd Pinkston hit the grass last week, his Achilles tendon torn, the Philadelphia Eagles' chances of winning the Super Bowl this season took a severe blow. With one of their starting wide receivers from last year's NFC Championship team out for the season, the Eagles were suddenly dependent on petulant receiver Terrell Owens, whose demands for a new contract have poisoned his relationship with the team. On Wednesday, the Eagles suspended Owens for a week after a heated argument with head coach Andy Reid. Now the Eagles have to decide whether T.O. (for whom quarterback Donovan McNabb has a feeling that "borders on hate," according to Peter King of Sports Illustrated) will be around this year, whether his noxious presence would be worse than his absence.

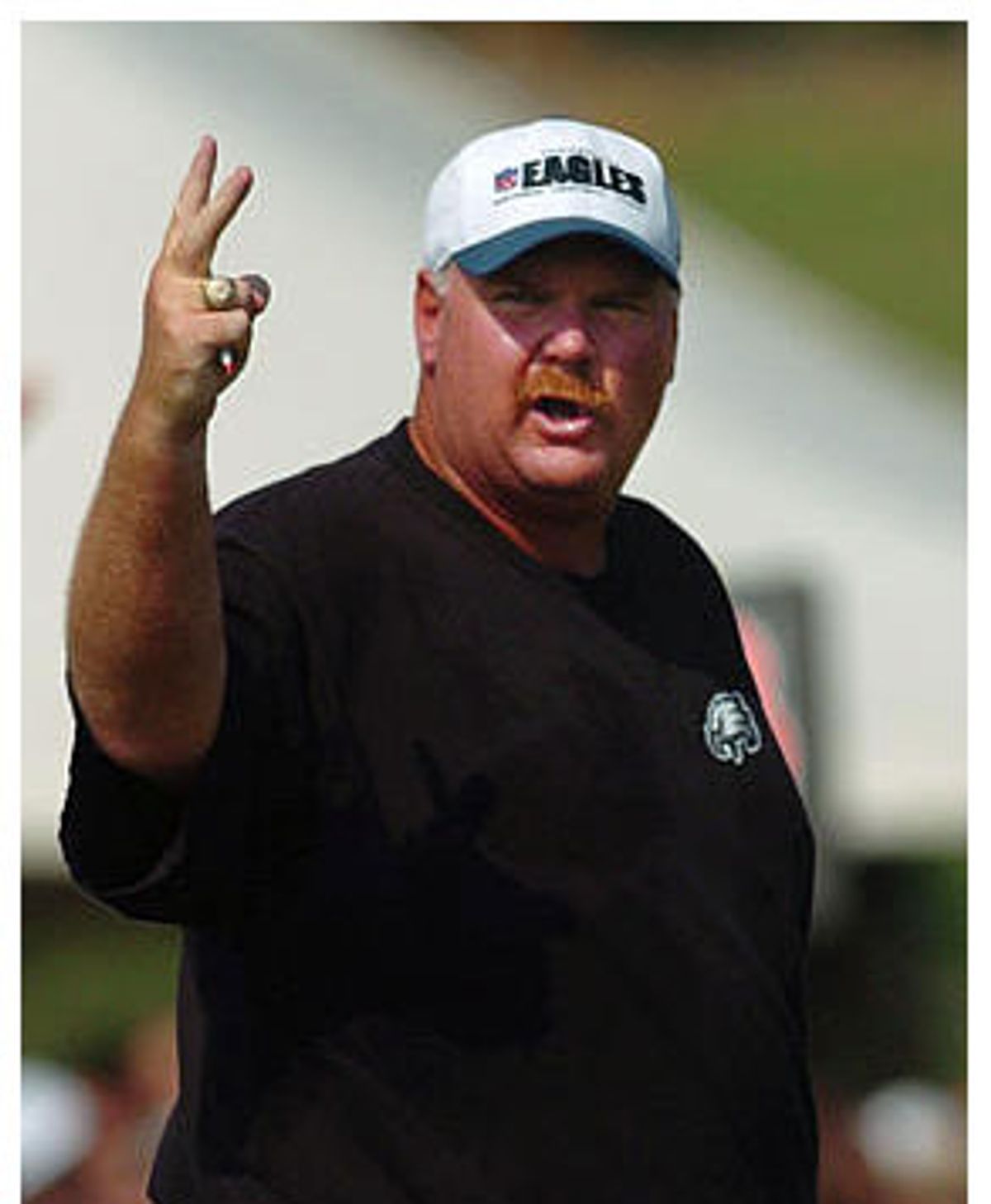

There's a lot to dislike about how this has turned out. It's too bad that T.O.'s career in Philadelphia appears to be over because his first year with the Birds in 2004 -- from the boisterous love Philly fans showered on him to his outstanding performance on the field -- looked like the beginning of a beautiful friendship. With the psychologically disordered Owens trashing Eagles management and bad-mouthing McNabb on ESPN Thursday, it now looks almost certain that he will be traded or benched. Which is a shame, because otherwise the Eagles would begin the season with arguably the best, most complete team the organization has ever fielded. The worst thing about the rotting relationship between T.O. and the Eagles, however, is that it overshadows the greatest obstacle to the Andy Reid-era Eagles finally winning a Super Bowl: Andy Reid himself.

By leading the Eagles to four straight NFC Championship games, Reid has earned the respect and admiration of Eagles fans. But despite his role in making the team one of the elite franchises in professional sports, Reid is plagued by two character traits that may block the Eagles from going all the way. As a big-game strategist, Reid is a timid coach who becomes more conservative under pressure. And his aversion to running the football runs counter to everything that history has taught us about how teams win Super Bowls. Now that the Eagles are once again having personnel problems at wide receiver, their inability to move the chains on the ground could prove fatal to their Super Bowl ambitions.

Even before Owens went nuclear, Iggles fans entered the season with a nasty hangover. They'd limped away from the television after the Eagles' Super Bowl loss to the New England Patriots with lingering questions. Chief among them: Why Donovan McNabb has a habit of vomiting during big games, but more important, why the Eagles didn't show any urgency during the penultimate drive of the game. After all, they trailed by 10 points with less than six minutes to go. Where was the hurry-up offense? They finally did score a touchdown but by then there was not enough time to get the ball back from the Patriots and tie the game with a field goal.

But if Eagles fans thought they'd get some straight answers about what happened, they were mistaken. Vomitgate went unresolved, with different people giving different accounts. As for Reid's brain lock in the fourth quarter, he refused to answer the question after the game, then on Monday made one of the more cerebellum-paralyzing statements ever made by an NFL coach. Claiming that he didn't really remember the Eagles' tortoise crawl up the field, Reid told reporters that he had "put that away a little bit," as if he were repressing an unpleasant memory. Then he said he was done addressing the issue.

As Eagles fans regrouped during the offseason, they had every reason to be leery of their quarterback and head coach. Any Eagles fan who has paid attention over the past few years is painfully aware of the tics that pervade Reid's offensive play-calling -- the quick out pattern to the physically unimposing Todd Pinkston, for instance, which has maybe once gained more than 1 yard in all the times Reid has called it. But these idiosyncrasies are part of a larger pattern.

First, there's Reid's strange lack of chutzpah. For a man who loves the trick play and who has opened more than one game with an onside kick, he pulls his head into his shell in the pressurized atmosphere of the post-season. The Eagles' Sunday stroll in the fourth quarter of the Super Bowl was not the first time that Reid lacked aggression in a high-stakes playoff game. The Eagles took their time developing a sense of urgency in their 14-3 loss to the Carolina Panthers in the 2004 NFC Championship Game, and in the 2003 championship game against the Buccaneers Reid declined to go for the jugular when the Eagles intercepted a Brad Johnson pass in Tampa Bay territory with a 7-3 lead in the first quarter. With the delirious crowd at Veterans Stadium howling for blood, Reid responded with ultra-conservative play-calling. The Eagles went three and out and wound up punting. That cleared the stage for Bucs wide receiver Joe Jurevicius, not known for his speed, to take a 10-yard crossing route on third down and, as Eagles fans watched in open-mouthed horror, race 71 yards down the sideline, setting up a 1-yard touchdown run by Michael Alstott. The Eagles never recovered.

But Reid's strange mix of recklessness and conservatism is not his biggest flaw as a coach. That distinction goes to Reid's well-established aversion to running the football. The West Coast offense that Reid employs is predicated on the short passing game. And to a certain extent, coaches who run any version of the West Coast offense substitute short passes for runs. But none of the coaches who have wielded the West Coast offense with any great success since Bill Walsh established it in the 1980s have eschewed the running game as much as Reid has in his six years as coach of the Eagles.

Being able to run is critical to a team's success. A team that runs the ball allows its offensive lineman to go on the aggressive and pound the other team's line, wearing it down, rather than backpedal in pass protection. A successful running game keeps the opposing defense off-guard: Rather than charging straight upfield at the quarterback, the other teams's defensive linemen have to be prepared to hold their ground. Success in the running game opens up passing lanes by forcing opposing linebackers and safeties to cheat up to the line of scrimmage, creating opportunities for the play-action pass.

Reid runs the ball less than all his West Coast counterparts except for Seattle Seahawks coach Mike Holmgren -- and less than all the coaches who ran Super Bowl-winning dynasties in the '80s and '90s. According to the unofficial statistics at pro-football-reference.com, 56 percent of the plays that Reid has called during his six years with the Eagles have been passes. Holmgren also averaged 56 percent during his seven years with the Green Bay Packers, but Holmgren's offense was less radically anti-run than Reid's. For one thing, the Eagles run stats are inflated by the fact that Eagles quarterback Donovan McNabb has averaged 65 rushes per season over his career, about 25 more rushes per season than Packers quarterback Brett Favre. And Holmgren's offense featured the power running of Dorsey Levens, as opposed to Reid's finesse approach.

The three most successful West Coast offense head coaches -- Bill Walsh, who won three Super Bowls in 10 years with the San Francisco 49ers; his successor George Seifert, who won two championships in eight years; and Mike Shanahan, who won back-to-back titles with the Denver Broncos -- all ran the ball more than Reid does. And in all seven of those Super Bowl seasons, their teams ran the ball more often than they did in non-championship years. Shanahan ran the most balanced attack of the three in his Super Bowl victories in '98 and '99. With Terrell Davis slashing downhill through the defense and John Elway throwing over the top, the Broncos passed the ball on just 50 percent of their plays.

And the same logic applies to the other coaching dynasties of the past two decades: Jimmy Johnson's Dallas Cowboys, who won Super Bowls in 1993 and 1994; Joe Gibbs' Washington Redskins, who won championships in 1983, 1988 and 1992; Bill Parcells' New York Giants, Super Bowl champs in 1987 and 1991; and Bill Belichick's Patriots, who have won three of the last four Super Bowls. All those teams ran the ball more often than Reid's Eagles, and they ran the ball with even greater frequency in the years they won the Super Bowl.

There are a couple of exceptions to the rule that stand out. West Coast acolyte Jon Gruden took over the Tampa Bay Buccaneers in 2002 and led them to the championship in a season in which they passed the ball 58 percent of the time. But with bruising running back Mike Alstott, Gruden's Bucs could run the ball when they had to. And they had the advantage that year of a dominating defense, which returned three interceptions for scores in their Super Bowl rout of the Oakland Raiders. The St. Louis Rams won the Super Bowl in 2000 after a regular season in which they passed the ball 55 percent of the time. But that team was loaded with a sickening array of talent -- two All-Pros at receiver in Torry Holt and Isaac Bruce; a future Hall-of-Famer in his prime at running back in Marshall Faulk; and a quarterback, Kurt Warner, having one of the best seasons of all time. While running the ball a lot doesn't guarantee victory, teams that can't run the ball don't win championships.

Reid's offensive philosophy is not without merit. The way he "flexes out" Brian Westbrook, for example, using him as a wide receiver, creates mismatches that opposing defenses struggle to parry. And Reid has myriad other positive qualities as a coach and general manager. But his disinclination to incorporate a power running game into his offensive philosophy runs counter not just to football wisdom but to the football gods, who ultimately award NFL championships to the teams that are most adept at kicking the snot out of their opponents, not tiptoeing around them.

Reid's run as coach of the Eagles represents the third time in the past 25 years that Philadelphia has controlled the NFC East. It happened first in the early '80s with Dick Vermeil, then for a brief period in the late '80s under Buddy Ryan. But none of that dominance has yielded a Super Bowl trophy. In that same period of time, the Eagles' division rivals, the Cowboys, Redskins and Giants, have won a total of eight Super Bowls. Today, Reid runs the risk of becoming the NFC equivalent of AFC coach Marv Levy, whose Buffalo Bills lost four straight Super Bowls from 1991 to 1994. None of Reid's success will count for much if the Eagles don't win it all while he's here. And unless he changes his offensive philosophy, that could be his legacy.

Shares