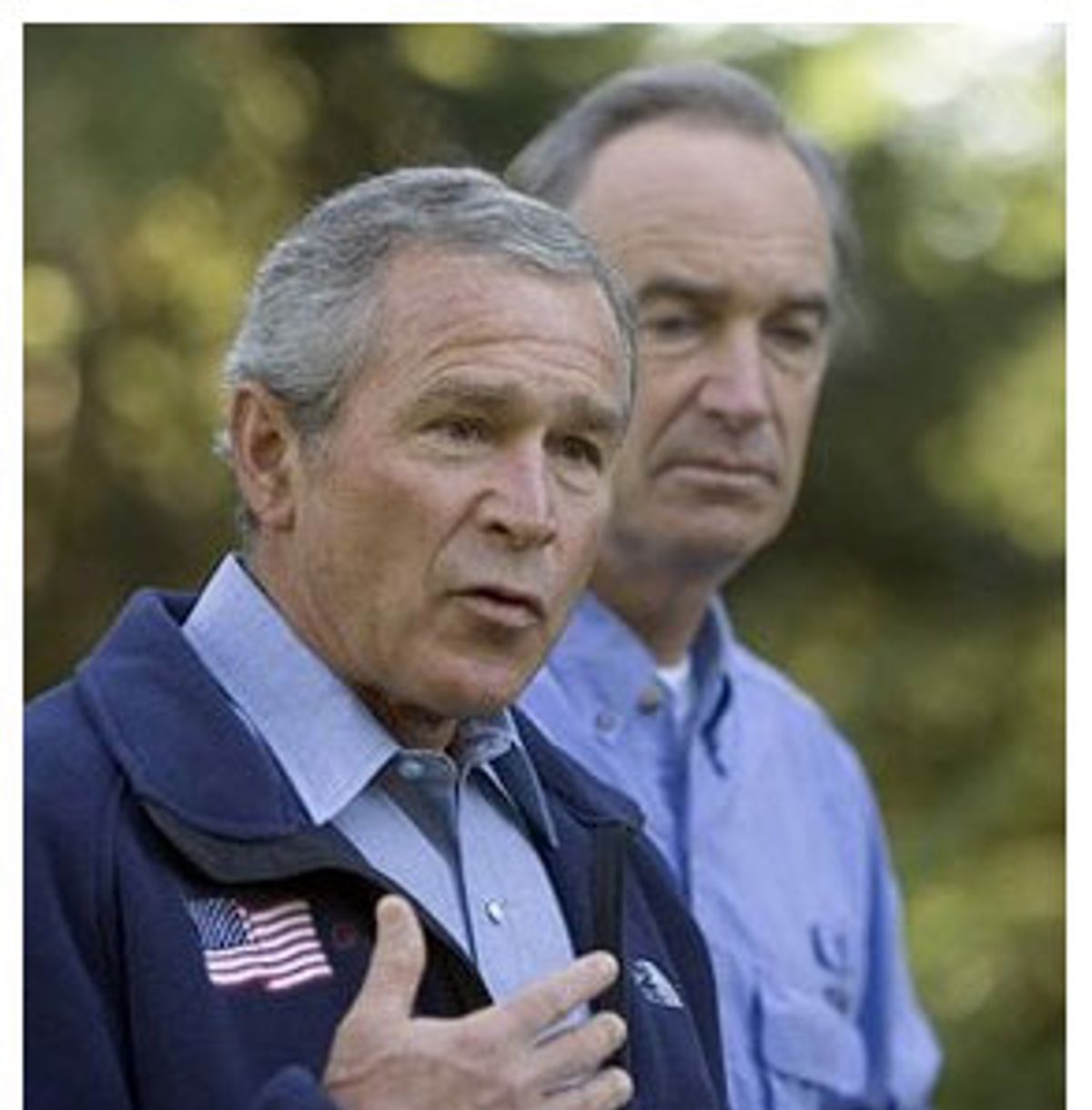

President Bush took a brief break this week from his monthlong vacation to deliver speeches in Utah and Idaho calling for staying the course in Iraq. Because American soldiers have died there, we must continue. "We will finish the task that they gave their lives for," Bush said in Salt Lake City on Monday.

He moved his vacationing in between to the Tamarack Resort in Donnelly, Idaho, where he made a short statement to the traveling White House press corps. He described the drafting of the Iraqi constitution as an "amazing event" in its guarantees of democracy and women's rights, and compared its deliberations to those at the Philadelphia convention that gave rise to the U.S. Constitution. "We had a little trouble with our own conventions writing a constitution," he said. Then he took a few questions.

"She expressed her opinion. I disagree with it," Bush said about Cindy Sheehan, the mother of a 24-year-old soldier killed in Iraq, who had camped outside the president's ranch asking for a meeting to hear her critical comments on the war. "I met with a lot of families. She doesn't represent the view of a lot of the families I have met with. And I'll continue to meet with families."

Later, Bush asked, "We've got somebody from Fox here, somebody told me?"

"Does the administration's goal -- I'll ask you about the Iraqi constitution. You said you're confident that it will honor the rights of women."

"Yes."

"If it's rooted in Islam, as it seems it will be -- is there still the possibility of honoring the rights of women?"

"I've talked to Condi, and there is not -- as I understand it, the way the constitution is written is that women have got rights, inherent rights recognized in the constitution, and that the constitution talks about, you know, not 'the religion,' but 'a religion.' Twenty-five percent of the assembly is going to be women, which is a -- is embedded in the constitution. OK. It's been a pleasure."

"What else are you going to do? Are you going to bike today?"

"I may bike today. Been on the phone all morning. Spent a little time with the CIA man this morning, catching up on the events of the world. And, as I said, I talked to Condi a couple of times. And tonight I'm going to be dining with the governor and the delegation from Idaho; spend a little quality time with the first lady here in this beautiful part of the world. May go for a bike ride."

"Fishing?"

"I don't know yet. I haven't made up my mind yet. I'm kind of hanging loose, as they say." With that, the questions ended and the vacation continued.

While Bush has allowed only abbreviated and controlled access for the press, he has been coddled by the Republican Congress, despite the spike in public disapproval of his conduct of the Iraq war.

In February 1966, Sen. J. William Fulbright, chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, held the first hearings on the Vietnam War, which were televised nationally for six days. The public was riveted by the penetrating questioning of administration officials and the debates among the members of the committee. Fulbright had been a friend of President Lyndon Johnson for years. Johnson, after all, had been the Senate majority leader, and Fulbright was a fellow Southerner. But the escalation of the war and the absence of a clear strategy of resolution prompted Fulbright to call the hearings. He held additional hearings in August 1966, in October-November of 1967 and, when Richard Nixon became president, in April-May 1971 for 11 days. Fulbright believed that it was his constitutional duty to exercise oversight of the executive.

No similar Senate hearings on the origins, conduct and strategy of the Iraq war have been held. During the Johnson period, the Democrats controlled both chambers of the Congress. But Fulbright did not feel that partisan discipline under the whip of the White House was a higher principle than performing as a check and balance. Fulbright was a Democrat raising pointed questions about the policy of a Democratic president. But no Republican Senate chairman has seen fit to follow the Fulbright example. The one-party Republican rule of the Congress has resulted in the stifling of inquiry. Abandoning its powers and duties, the Republican Senate as a body refuses to hold the executive accountable.

The Democrats, suffering the debilities of the minority, are a congressional party without authority to initiate committee hearings. They cannot set an agenda or command television cameras. Their Republican colleagues have shunted them to the sidelines; the White House is deaf to their entreaties. Sen. Joseph Biden of Delaware, the ranking Democrat on the Foreign Relations Committee, after fact-finding missions to Iraq, has offered numerous ideas to the administration, none of which have been accepted. Biden's good-faith effort at offering helpful practical advice has been ignored as though he had said nothing.

The opposition party cries in the wilderness. There is no specific policy on Iraq coming from the Democrats that the administration will heed other than blind support. It is impossible for the Democrats to be expected to arrive at answers to problems about which they, like the public, have been denied essential information. Why should Democrats produce polished answers when the administration won't or can't explain itself? Developing hard-and-fast positions on particular difficulties in Iraq will not make the White House hear them. The Democrats' greatest potential strength now is simply to ask questions.

The unanswered questions of consequence that might be asked, if there were a responsible Congress to pose them, are many, extending from Iraq to Iran, from public diplomacy to intelligence, and to the fate of our military.

On Iraq: Why was it necessary for the Bush administration to impose an arbitrary deadline on the drafting of the Iraqi constitution, the single most important document for a new Iraq? The constitution appears to undermine the administration's commitment to a unitary state and to democracy, and enshrines Islamic law as a basis of governmental legitimacy. Why didn't the administration allow the Iraqi communities to attempt to arrive at acceptable compromises on their own timetable?

Recent reports, including in the Washington Post, document the growth of sectarian militias that engage routinely in abductions, assassinations and other violence against domestic opponents. In many towns and cities, these militias have supplanted or run national security and police forces. What plans does the administration have to contain or disband them? Are there any plans for integrating these militias into national security forces so that they lose their sectarian identity and command structure? If there are no such plans, what analyses has the administration done to determine the future effectiveness of an Iraqi national security force in this environment?

On the U.S. military: Retired four-star Gen. Barry McCaffrey, reflecting the views of many senior officers, has stated that "the wheels are going to come off" the military in Iraq in 24 months and that the Reserve and National Guard systems are approaching meltdown. What is the administration's strategy for ensuring combat readiness and preparedness? Are the various conflicting statements by administration and military commanders on the withdrawals of some troops dictated by this meltdown or by some assessment, not yet publicly articulated, of the security conditions in Iraq?

Gen. Schoomaker, the chief of staff of the Army, has declared that U.S. troops may be stationed in Iraq for at least four more years. Where will these troops be found?

As of May 2005, the U.S. military has plans to build four large bases in Iraq -- each designed to hold a brigade-size combat team, aviation units and other support personnel -- that have the air of permanence. Does the administration intend to establish these as permanent U.S. bases? What is the long-term strategy behind their construction? How will the current levels of U.S. forces in the region extended over a period of six years affect other potential security contingencies?

On Iran: When asked about military action, President Bush has stated that all options are on the table regarding Iran. Has the administration drawn up military options? What are the assessments of military analysts of likely outcomes in exercising such options?

The administration has emphasized that Iran is a proliferator of weapons of mass destruction, a major supporter of terrorism, and a notorious violator of human rights. Recent reports in the press have documented that Iran is the principal funder of the leading Shiite political parties and militias in Iraq. Iran has also expanded its influence in Lebanon through Hezbollah's gains in legislative elections. What assessments has the administration made about Iran's response to any U.S. military action against it?

German Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder has declared he would not support such an action. Which allies have agreed to support the administration's military option in Iran? What responses has the administration planned to deal with a military action against Iran within international bodies including the United Nations Security Council and NATO?

On U.S. intelligence: Has the administration commissioned a National Intelligence Estimate for military options against Iran? Has the new director of national intelligence John Negroponte assured the intelligence community that its objectivity and integrity will be protected from any political pressure? Will the DNI prominently raise caveats from intelligence analysts where there are disagreements? Will any new NIE be shared with the Congress in a timely fashion before any debate of any action is undertaken?

The administration has used Republican members of the House of Representatives in the past to attack senators of both parties for raising serious questions about the administration's policies. (Rep. Duncan Hunter's attack on Sen. John Warner for conducting hearings on Abu Ghraib is a notable example.) Will the president take steps to ensure that the oversight responsibilities of the Congress are not compromised or inhibited? Will he make every effort to inform his political aides that they are not to interfere with the congressional oversight process so that information and analysis are not twisted by political criteria?

On oil: The president recently signed an energy bill that provided no new measures for lessening U.S. dependence on foreign oil. In the absence of a commitment to achieve more energy independence, what measures does the administration propose to Arab nations to guarantee a steady supply and stable price of oil? The administration's advocacy of opening the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil exploration would have only a marginal and transient impact. What conservation measures does the administration propose?

On U.S. alliances: A number of member states in the coalition involved in the Iraq war and occupation have withdrawn their troops. Has the administration drawn up plans for our military to fill these gaps now and in the future? What policies does the administration plan to create a more cooperative environment, especially within the Western alliance? Does the president plan to consult fully with our historic allies on military options in the future? Has the administration shared its military options involving Iran with key allies? If the administration does not plan to change its policies on extra-legal actions, such as going to war without advance consultation, how does it propose to strengthen our traditional alliances? With Iran and Iraq under the sway of Shia fundamentalism, how does the administration plan to encourage the cooperation of other Arab nations in the region?

On public diplomacy: Longtime Bush political aide Karen Hughes has recently been confirmed as undersecretary of state for public diplomacy and public affairs. Two previous appointees have resigned this post in frustration. With U.S. prestige at an all-time low throughout the world, according to several polls conducted by independent organizations such as the Pew Trust and the German Marshall Fund's Transatlantic Institute, what policies does the administration plan to change to reverse this trend?

Given that the draft Iraqi constitution enshrines Shiite Islamic law restricting the rights of women, how does the new undersecretary explain the administration's acquiescence in such an obviously undemocratic development? How does the undersecretary explain the administration's goal of spreading democracy in the Middle East given that the process of constitution drafting in Iraq has alienated secular Iraqis, Sunnis and Kurds and aligned the U.S. with the dominant Shiite factions heavily influenced by Iran? In pursuing its stated goal of democratization the administration has particularly focused on Sunni-ruled nations -- Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Syria. What does the undersecretary offer as incentives to these nations in the light of the administration's failure to protect Sunni and women's rights in Iraq?

The Pentagon continues to block a federal court order to publicly release photographs and videotapes of torture committed at the Abu Ghraib prison. The president has threatened to veto the military appropriations bill if an amendment sponsored by three Republican senators, John McCain, Lindsey Graham and John Warner, that would outlaw torture and abuse of prisoners is attached. How does the administration foresee any change in the international perception of the U.S. image if it continues to follow these policies?

The president's policy has involved his abrogation of U.S. adherence to the Geneva Conventions that protect prisoners against torture. Will the administration pledge to comply with these conventions in the future? Will the administration permit the International Red Cross unfettered access to all prisoners under U.S. supervision?

These are only some of the pressing questions that might be asked by members of Congress. The Republican Congress has left a vacuum of responsibility. Raising these matters would not merely foster necessary public debate. It would stir to life the legislative branch and begin to show what an energetic Democratic majority might do on the public's behalf.

Sen. Fulbright was the first to critique the pathology of the imperial presidency that he called "the arrogance of power." He also stands as a political exemplar. Fulbright's fearlessness, skepticism and precision present a historical model for the Democrats, even if they lack his committee chairmanship.

Only by asking questions can the Democrats hope to determine the substance of Bush's increasingly evanescent and futile policies to which they are supposed to respond. Only by asking questions can they demonstrate that they understand the nature of the Congress and should be granted control in it. Question time is their opportunity and obligation.

Shares