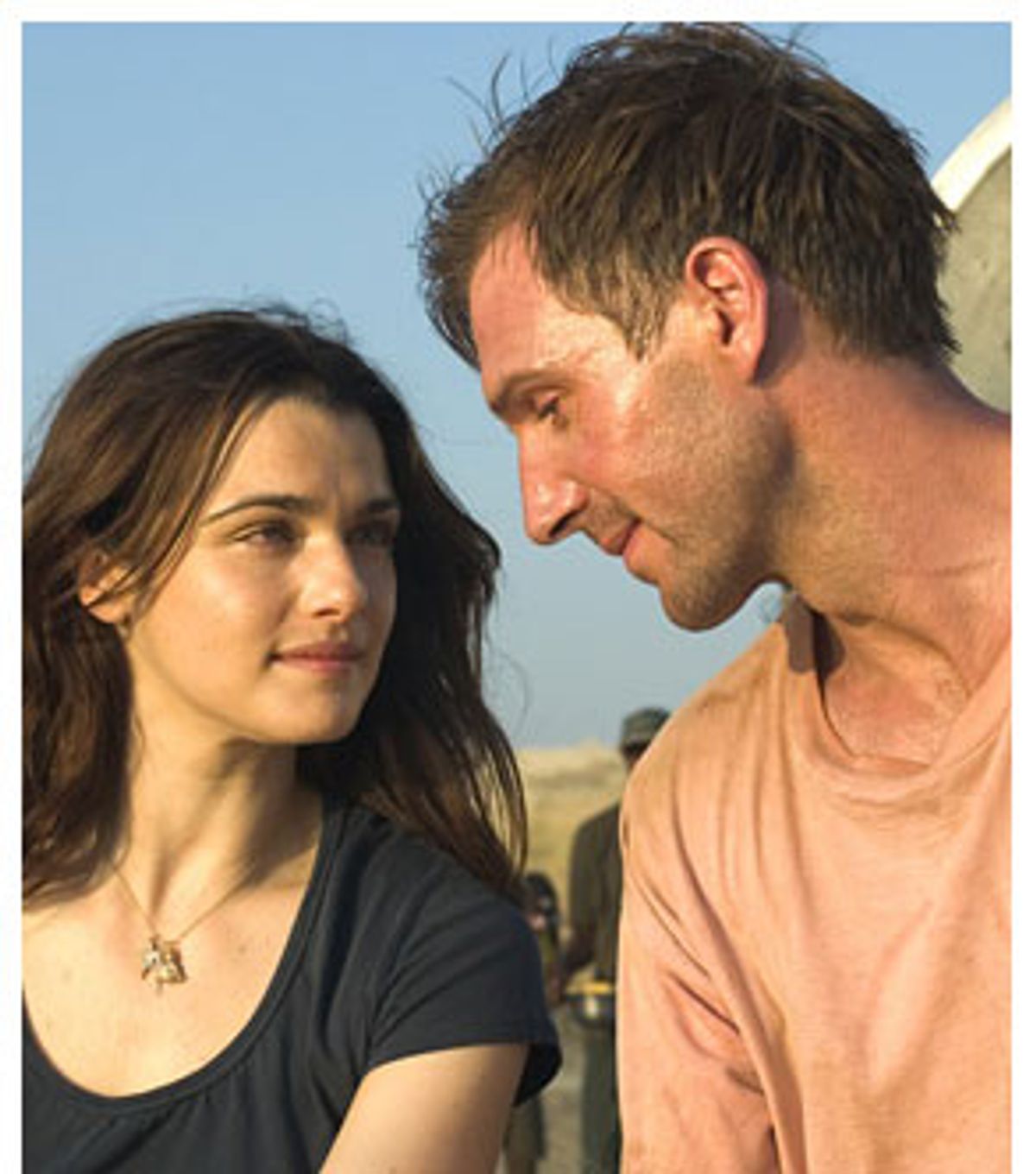

In a remark that may be more clever than it is true, Katharine Hepburn said of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, "She gave him sex; he gave her class." In Fernando Meirelles' adaptation of John le Carré's "The Constant Gardener," Rachel Weisz doesn't need class. But Ralph Fiennes needs sex, and part of the wonder of this earnest, carefully crafted political thriller is the way Weisz draws out in him a guarded sensuality that's all the more affecting for how tentative it is.

Weisz and Fiennes play husband and wife: He's a quiet, decent English diplomat, with the pheasant-under-glass name Justin Quayle, who believes he knows how the world works; Weisz is Tessa, an activist who actually goes out into that world to shake it apart. And while the "constant gardener" of the title is most obviously Quayle (he spends much more time fussing over his rhododendrons than effecting diplomacy), it's Tessa who does the more constant tending, and not just when it comes to sexual nurturing: The grand, dark joke of the movie is that it's she who exterminates his political naiveti, as if it were a deadly garden plague.

"The Constant Gardener" is a political thriller in which love saves the day, sort of, but we're talking about a deeply pragmatic kind of romanticism: This is love harnessed in the service of muckraking. Meirelles made waves a few years ago with "City of God," about a gang of kids running wild in a Rio de Janeiro slum, a picture that managed a rough kind of vitality in the corners -- in other words, when Meirelles wasn't meticulously drawing our attention to the grittiness of the story. Oddly, or maybe not, Meirelles is better at adapting le Carré: Instead of just riffing on stereotypes of English repression, he seems to understand that repression actually reinforces, rather than negates, the presence of sexuality. (If it weren't there in the first place, what would there be to repress?)

Meirelles is way too fond of jiggly hand-held-camera effects -- the camera is much more effective at capturing the subterranean emotional turbulence of the story when it's held steady. But he is in tune with his lead actors, and they're beautifully in tune with each other: Fiennes, for once, plays a man instead of a stick figure; even his seemingly toothless, jack-o'-lantern smile carries a hint of sadness here, instead of seeming like a liability he can't help, as it usually does. And Weisz, always a lively and appealing actress, is compelling here in a way she's never been before. Her character dies in the movie's early minutes (that's not a spoiler -- her death is the event that sets the picture in motion), but she lives on in flashbacks. Each time she appears, the movie gets a few more gradations of light and texture, and a few more provocative angles. Meirelles uses her scenes as if they were multidimensional, Escher-like building blocks, each one a mystery by itself, reaching up toward a shimmery conclusion.

As the movie opens, Tessa is headed for a remote reach of Kenya with her colleague, a doctor named Arnold (Hubert Koundé ). It's not immediately clear to us exactly what their work is, because Quayle doesn't know, either: He and Tessa, after an unlikely courtship, have married and come to Africa together. In a flashback scene, we see Tessa, before their marriage, begging Quayle to take her along. Quayle, surprised but intrigued by the proposition, mutters something about how they hardly know each other. "You could learn me," she implores, and a cautious flicker of a smile crosses his face, the first clue we get that her impetuousness speaks to something deep inside his solid heart.

It turns out that Tessa has come too close to unlocking a secret involving a pharmaceutical conglomerate. But Tessa's death reveals some other secrets to Quayle, and out of frustration, grief and an anger he doesn't want to allow himself to feel, he sets out to unearth the truth behind some of the mysteries she has left in her wake.

While Tessa sees bureaucracy as the enemy, Quayle is the sort of man who has always had faith in the system, and not just because it has given him such a comfortable life. He needs to believe in a sense of order -- he needs to believe that, with some brainpower and a bit of paperwork, everything will shake out right in the end. Although that may sound like stereotypically English stiff-upper-lip machismo, in Quayle it's the exact opposite: Unlike Tessa, Quayle is far too sensitive to face up to chaos. "The Constant Gardener" goes beyond making the point that the political is personal; it shows how the bureaucratic can be personal too -- the mechanics of the system can be a comfort to us not necessarily because we're lazy or uncaring, but because without them, we're not really sure how to proceed. (As Fiennes' superior, Danny Huston, in a rather too-large supporting role, comes much closer to a blobby version of the stiff-upper-lip cliché.)

Through much of "The Constant Gardener," Quayle is the very definition of uncertainty. This is a mystery, but the biggest question is not the exact nature of the corruption Tessa was about to uncover before her death (that's revealed fairly early in the plot); it's how far Quayle will go to set things right. This is a picture with a slow-burning sense of outrage: It's not nearly as passionate as, say, last year's "Hotel Rwanda." (What's more, it's not based on a true story -- although the movie's end credits include a note from le Carré, stating that even though his story isn't based on actual events, his research into the workings of pharmaceutical companies suggest that their practices may be even more heinous than what he's shown us.)

Even so, this is a picture with sturdy liberal underpinnings: It's just that Meirelles and screenwriter Jeffrey Caine do their crusading quietly, instead choosing to put most of the focus on the actors, and not just on the leads. Some of the movie's secondary characters increase its potency exponentially, considering they have relatively little screen time: The always-astonishing Bill Nighy appears as a lizardy high government muckety-muck -- he pulls off the amazing feat of uttering most of his lines while barely parting his teeth. And British stage actor Richard McCabe has a lovely turn as Tessa's cousin, Ham: In just a few small scenes he delineates the close kinship that sometimes thrives between people who've known each other all their lives.

Meirelles clearly trusts his actors, particularly Fiennes and Weisz: The plot of "The Constant Gardener" is fairly intricate, but in the end, the story is told mostly in their faces. Weisz has never been better: She's joyously expressive and alive, but there's gravity beneath that milkmaid complexion. She's grounded even when she's being flirtatious. And Fiennes has never been more moving: Occasionally, Quayle looks at Tessa with a kind of helplessness -- not weakness, but simply an inability to reconcile what's so wondrous about her with the clear-cut, organized world he so deeply believes in. In the end, he realizes that there's no reconciliation between the two. She's his tragedy, his salvation and his perfect partner: He does everything she does, only backward, and in oxfords.

Shares