The best of all time. It's a silly expression, one that conjures up teenage arguments in which Eric Clapton squares off with Jimi Hendrix, or Shakespeare goes mano a mano with Dante. There's really no settling these arguments. Even in the world of sports, in which victories, records and statistics offer objective ways to measure greatness, the disputes will never end. Was Ted Williams greater than Barry Bonds? How about Unitas vs. Montana? Sampras vs. Laver?

But one athlete was so far above the rest that it is impossible even to imagine his competition. Jerry Rice, who announced his retirement Monday, was indisputably the greatest receiver of all time. "He was probably the greatest player of his era," his former coach, Hall of Famer Bill Walsh, said. And you could make a case that he was simply the greatest football player of all time -- period.

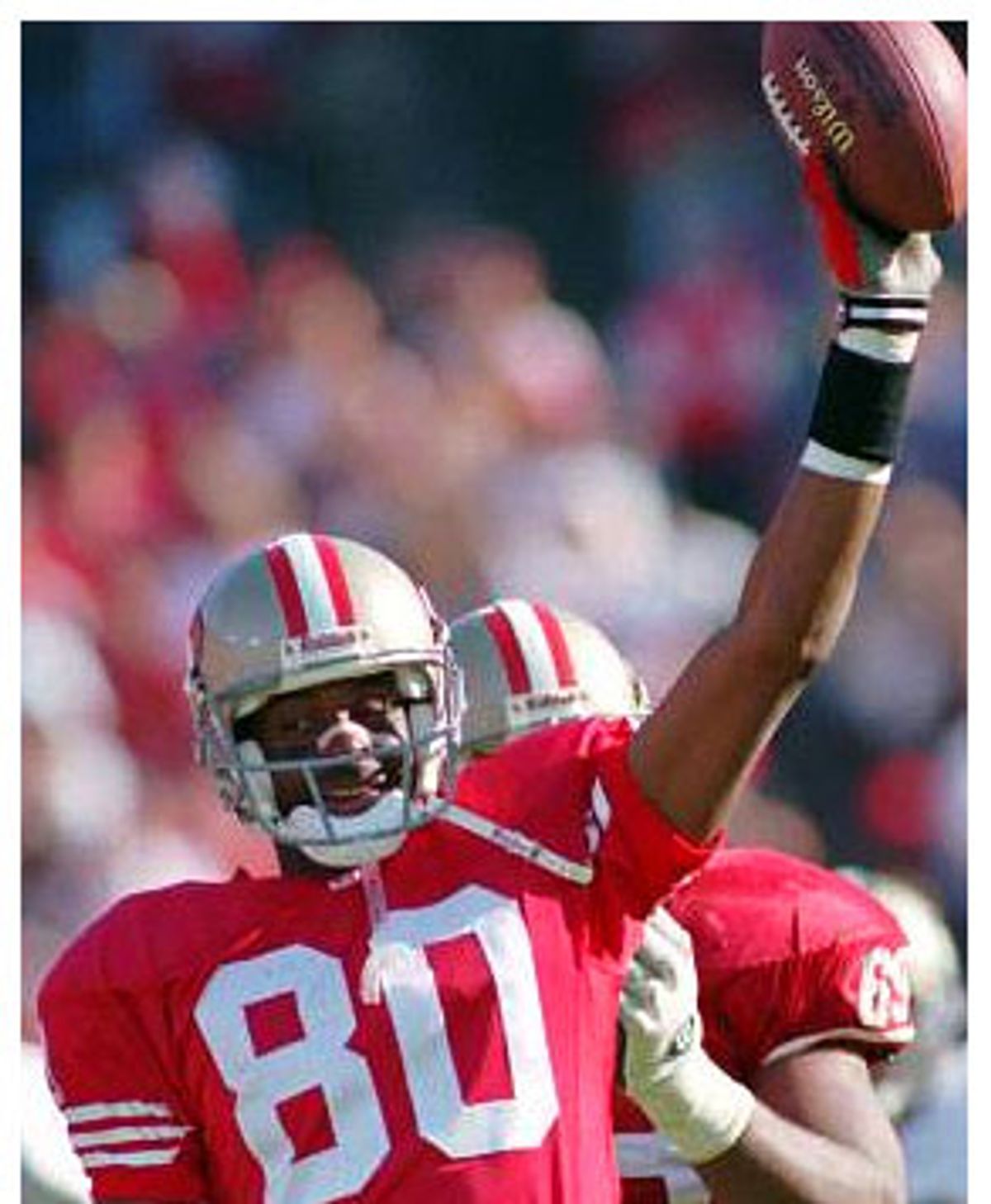

In 16 seasons, Rice played 238 games for the San Francisco 49ers. I think I saw 236 of those games. Like tens of thousands of 49er fans, and millions of football fans across the country, I was blessed: For 16 years we got to watch someone who was better at what he did than anyone else has ever been. Every sport has certain images that sum up greatness: Michael Johnson flashing around the final turn in the 400 meters, Michael Jordan drilling the game-winner at the buzzer, Willie Mays whirling to throw home. To that list, add this one: No. 80 reaching out to catch a pass, turning upfield and running -- and now that the image will never be more than a memory, running forever.

If God had sat down to make a wide receiver, he would have whittled out Jerry Rice. At 6 feet 2 inches and 200 pounds, Rice was taller and heavier than most cornerbacks, but just as fast as them, or faster, with the exception of a few blurs like Washington's Darrell Green or Deion Sanders. Receivers, like football players in general, are getting bigger and faster: Terrell Owens, at 6 feet 3 inches and 226 pounds, is a super-muscular freak, but there are more and more wideouts in the mold of Randy Moss (6 feet 4, 210). But since no one, no matter how big, is ever going to break even a fraction of Jerry Rice's ridiculous laundry list of receiving records, he gets to claim the prototypical body type.

Jerry Rice didn't do any one thing on the football field better than anyone else. He didn't have hands like Cris Carter, didn't have the strength of Terrell Owens, the speed of Randy Moss, or the grace of Lance Alworth or Lynn Swann. But no one else had all of those things combined as much as he did. And it wasn't what Rice did on the football field that ultimately set him apart. It was what he did off it.

NFL football is a brutal and exhausting game. Everyone on the field is world-class at what they do. There are something like 600 people who start in the NFL, and they are bigger, stronger and faster than anyone else, including the thousands of gifted athletes who play major college football. The game involves frequent massive traumas to all the muscles and bones in the body, followed immediately by all-out exertion. Your career can end at any moment. Every player drives himself year-round as hard as he can to make himself stronger, tougher, more agile, faster. Pain and sacrifice are the currency of the league.

In this elite company of willpower-driven warriors, Rice was the champion. His off-season workout regimen was legendary. "He just works harder than anyone else," Barry Bonds once said. Rice's workout routine consisted of morning cardiovascular work and afternoon strength work. Rice would run fast up a steep five-mile trail on a course called The Hill, pausing at the steepest section to do 10 -- yes, 10 -- 40-meter wind sprints. Roger Craig, the former 49ers running back and himself a superbly conditioned athlete, ran The Hill with Rice. Afterward, Craig said he felt like he was going to die. In the afternoon, Rice would do weight work -- 630 repetitions' worth.

It was an inconceivable amount of pain. But it would be paid back. It would be paid back in the fourth quarter, with the game on the line, when Rice would line up across from his body double on the other side of the line of scrimmage, a young man just as fast and tough and strong as he was, paid millions of dollars to follow Rice like his own shadow, but who maybe hadn't stuck through all of those 40-meter wind sprints when every breath was a spear in the chest. And so when Rice would burst off the line and run that slant, Body Double would start out right there, backpedaling fast, staying with the move, swiveling -- and then the debt would be collected, as Body Double's powerful legs wouldn't answer and suddenly Rice would be running free, alone, the way he ran up that trail.

They call what Rice had "football speed." Football speed is how fast you run in a game, not on a track with a coach clicking off your 40 time. Rice never came close to matching the speed of Bob Hayes or Warren Wells -- there were even reports in the days when they were teammates that Steve Young was as fast as he was (which wasn't that much of a dis, because Young was fast.) But on the field, in his prime, Rice was almost never caught. And when he was running under a deep pass, being chased by a free safety or a corner who on paper was faster than he was, he always got there first. Speed is about heart. Actually it's about two kinds of heart: the one that beats, and the one that beats other people. Jerry Rice had a lot of both kinds, which is why he beat more people than anyone else in the history of football.

I saw that football speed from a few feet away at the San Francisco 49ers' training camp in 1987. Here's how I described it years later.

"I was watching defensive backs drilling against wide receivers. No linemen were involved. Joe Montana was the quarterback, Jerry Rice the receiver. The players were in shorts and light pads. The defensive back, Darryl Pollard, lined up about four yards off the line of scrimmage from Rice. I was standing just behind Montana. A ringside seat at Mt. Olympus.

"At the snap of the ball, Rice took off upfield. On television, I had always noticed his odd running style, at once fluid, powerful and almost mechanically repetitive, with his upper body kept very straight. Standing a few yards away as he accelerated like a drag racer at the backpedaling Pollard, I realized, with a sympathetic shudder for the defensive back, not only that Rice was much faster than he appeared to be on TV, but worse, that his almost exaggeratedly efficient stride was absolutely unreadable: No shift in body weight, no slight tilt, betrayed either a fake or a move.

"It was like watching a very fast robot. After 20 yards, the robot's feet executed a double fake, rightleft. The two stutter steps took about a tenth of a second. Incredibly, Pollard didn't bite on the left move, but he was forced to react to it, turning his hips just slightly to his right. At exactly that instant, Montana released the ball and Rice pushed off his left foot and cut upfield to the right on a post pattern, not breaking stride, his body still as straight-up and robotic as ever. He suddenly appeared under Montana's pass -- which had been thrown before the cut to an empty space on the field -- snatching the ball out of the air with his big hands just as Pollard, who had spun back from his right and closed ground with extraordinary rapidity, jumped high into the air, missing the ball by inches. Rice jogged back to the line of scrimmage, expressionless."

Some critics try to play down Rice's greatness by pointing out that he played for Bill Walsh, whose West Coast offense befuddled defenses that had not yet figured out how to respond to its complicated short-pass system, with multiple fast reads for the quarterback and option routes. They also point out that the guys throwing balls at Rice for most of his career were named Montana and Young. That's all true. But after watching Rice run that post pattern that hot summer day 18 years ago, I don't buy it. Jerry Rice would have been great with Ryan Leaf throwing to him.

There are so many Rice memories, it's hard to pick one. But one play has always stood out for me. It was from perhaps Rice's greatest game -- Super Bowl XXIII against the Cincinnati Bengals, the thriller won in the last seconds when Montana hit John Taylor in the end zone after Taylor had lined up on the wrong side. Rice caught 11 passes for 215 yards and a touchdown and was named the MVP of a Super Bowl that some still say was the best ever. But the most important pass was not his TD but one he caught on the final drive, with the clock running out.

A penalty had put the 49ers in a deep hole -- second-and-20 from the Bengals' 45. Everybody knew the 49ers had to throw and pick up at least 10 yards. Everybody knew they were going to Rice. The Bengals knew it and double-covered him. Rice lined up on the right and ran a deep square-in. This was not a pattern he ran very much -- his signature patterns were the quick slant, or the post. It's a dangerous pattern. It takes the receiver horizontally across the field, where he can be creamed by a safety or a linebacker in a deep drop. It's also hard to throw -- it's tricky to lead receivers running sideways. Rice beat the double coverage. Montana led him perfectly and Rice snatched the ball out of the air, beat the safety, and ran for 27 yards. Taylor later scored the winning touchdown, but that was the play that won the championship for the 49ers. Afterward, one of the Bengals defenders said they had the play covered: "It took a perfect throw and catch."

Those who watched Rice grew accustomed to perfection. It's going to be a hard adjustment to reality.

My final memory of Jerry Rice has nothing to do with football. My aunt Wendy was a huge Jerry fan. She had his No. 80 jersey and screamed louder than anyone else at 49er games. She adored the guy. Wendy had hepatitis that she had incurred from a bad blood transfusion decades earlier. After defying all prognoses and living years longer than she was supposed to, her liver finally began to fail. No donor livers came in. Her other organs began to fail. She was dying. A nurse at the Stanford Medical Center who knew her happened to know Jerry Rice and mentioned to him that she might appreciate a call.

Jerry Rice called my aunt, who could no longer speak -- she could only grunt. A friend who was present told me that he talked to her for a few minutes, told her to stay strong. The man who embodied strength, who had faced down The Hill, was trying to raise the spirits of a dying woman who could no longer raise her head. No press was there and no one knew about it. Afterward, the friend reported that Wendy's eyes were shining. She passed away a few days later.

207 touchdowns. 1,549 receptions. 22,895 receiving yards. An infinite number of memories. And one phone call.

Thanks, Jerry. You were the greatest.

Shares