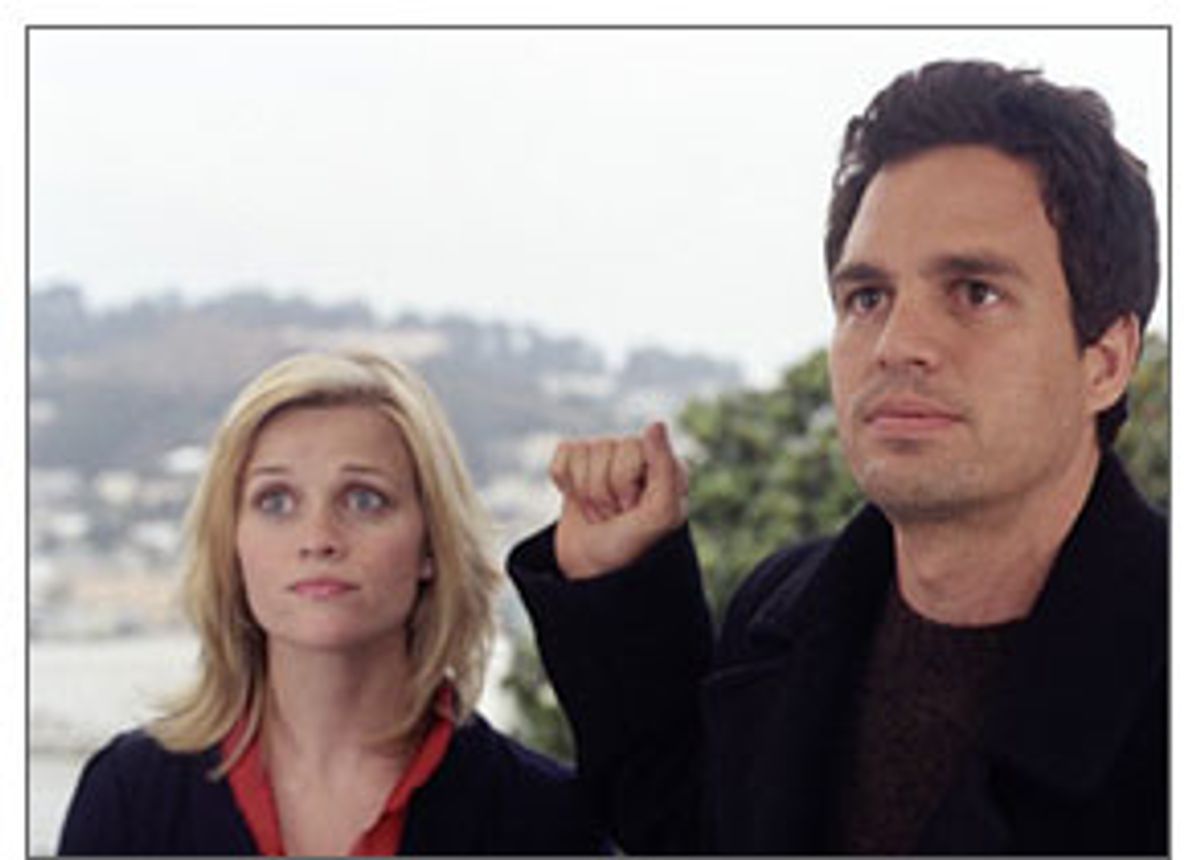

In "Just Like Heaven" Reese Witherspoon plays an ambitious young doctor who has sacrificed her personal life at the altar of Dr. Kildare. She's driving along one night, after having spent some 2,346 straight hours on duty, when -- sacre bleu! -- she's dazed by the lights of an oncoming truck. Cut to Mark Ruffalo schlepping, with a pushy real estate agent, through various San Francisco sublets, none of which is even close to right. Deeply depressed, for reasons we don't learn until later, he's essentially seeking a comfy couch with a few walls around it. He finally finds the perfect sofa for his despondent butt, and just as he's sinking into it, he begins seeing things: namely, Witherspoon, who shows up, along with her reproachfully pursed lips, to lecture him every time he puts a glass on the coffee table without using a coaster. What, she demands to know, is Ruffalo doing in her apartment?

All of that happens in the first 20 minutes of "Just Like Heaven." If you want the remainder of the picture to hit you like the ton of bricks that it is, please read no further. Those who prefer to keep their pates intact will want to know that Witherspoon isn't dead; she's only sleeping -- in a coma, to be precise. Her body lies in a hospital bed, attached to a bunch of tubes and wires, while her spirit roams the earth, nagging distraught young men about their housekeeping habits. Ruffalo is the only one who can see her, and the only one who can save her when an obnoxious hotshot doctor at the hospital (played with brio by Ben Shenkman), Witherspoon's former rival for a big job, tries to lobby for pulling the plug.

Let's forget, for just a moment, the whackbird ethical angles introduced by that plot twist. "Just Like Heaven" is really nothing more than your standard love-from-beyond-the-grave squishfest (even though the heroine isn't actually dead) done up in the dumb bonnet-and-bloomers get-up of contemporary romantic comedy. And maybe not surprisingly for a movie that so aggressively values the spiritual over the corporeal, it's desperately lifeless. The actors clutch at each other without ever stirring up even the most elementary chemistry: Ruffalo's trademark dazed quality has a narcotizing effect here, and Witherspoon comes off as a pert little nag. The jokes wobble and sail past their marks far more often than they hit. And the movie's ultimate message -- something like "Live your life to the fullest, lest you ever get hit by an oncoming truck" -- lumbers toward us with elephantine obviousness.

Even beyond that, the chiming right-to-life undertones of "Just Like Heaven" are especially distressing in the aftermath of the politicization of Terri Schiavo. (It would be all too easy for certain religious or political groups to seize the movie as an anthem for their cause.) But to be fair to the movie's director (Mark Waters, who made the highly entertaining and sharp "Freaky Friday" and "Mean Girls") and writers (Peter Tolan and Leslie Dixon, adapting Marc Levy's 2000 novel "If Only It Were True," a whopping bestseller in France), it's important to point out that the movie doesn't seem to have been crafted with any nefarious religio-political purpose in mind. (And it would already have been in postproduction, at least, when the Schiavo case exploded.)

What's worse is that the movie barely even recognizes that the decision to terminate life support is always -- no matter how we may feel about government intervention in the Schiavo case -- difficult for families. Witherspoon's sister (played by Dina Waters), when pressed for her reasons for pulling the plug, tearfully mutters something about how stressful the whole ordeal has been for her two little girls (who are seen in the background having a rip-roaring time at the little tea party they've set up, seemingly unfazed by the whole ordeal). Almost as an afterthought, Sis adds that she knows this is what her sister would have wanted.

Romantic comedies don't necessarily have to adhere strictly to reality. But they shouldn't manipulate us past the breaking point, either. Personally, I think protecting your progeny's right to a childhood full of angst-free tea parties is probably not a morally defensible reason for pulling the plug on your sister, but that's beside the point. The bigger issue is why we have to suffer the purgatory of romantic comedies like this in the first place. It's enough to make you feel like an eternally rootless spirit.

Shares