A couple of years ago I was talking to a prominent liberal political columnist at a New York cocktail party. We had met before, and knew we didn’t precisely see eye to eye. I said something pretty innocuous — or so I thought — about the 1972 presidential campaign, suggesting that it might be time for journalists and historians to take another look at that momentous event, which had so profoundly shaped American politics of the past 30 years.

“No it’s not,” said Mr. Columnist, cutting me off. “Because in this case the conventional wisdom is right. The left took over the Democratic Party, and it was a total disaster.”

I don’t really know whether Mr. C’s analysis is right or wrong; he is certainly more experienced in politics than I am. But what struck me was the fact that he didn’t want to talk about it. Three decades later, the Democratic Party mainstream still can’t face the living ghost of George McGovern, who challenged the party to live up to its ideals and then led it to one of the worst defeats in the history of American electoral politics.

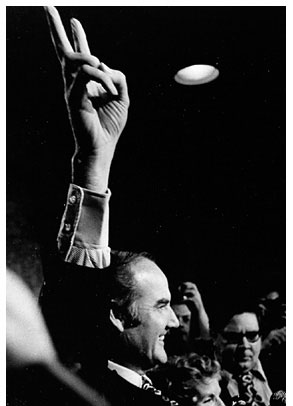

If that last sentence summarizes the facts about McGovern’s epochal 1972 campaign, those facts are open to endless interpretations, and pose more questions than they answer. Stephen Vittoria’s forceful pro-McGovern documentary, “One Bright Shining Moment,” offers one interpretation, and it’s not going to make Mr. C very happy. It’s a deeply flawed film but also an important one; if it does nothing else it should bring this decent and courageous prairie populist, whose very name has become a patently unfair term of abuse, before at least a few members of a new generation.

Drawing on archival footage, interviews with many key figures in and around the campaign — including Gary Hart, Frank Mankiewicz, Warren Beatty, Dick Gregory, Gloria Steinem and Gore Vidal — and extensive cooperation from McGovern himself, Vittoria argues that the South Dakota senator was never the wild-eyed radical or squishy-jawed pinko depicted by his opponents. Indeed, McGovern was a decorated World War II bomber pilot, a former Methodist seminarian and a history professor. His entire political career was predicated on a moral opposition to war and militarism, and a corresponding belief in America as a social, economic and political power.

McGovern was one of the very few American politicians to grasp in the early ’60s that the military establishment’s understanding of the situation in Vietnam was flawed, and that John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson were pouring American and Vietnamese lives by the thousands down a sinkhole. Parts of “One Bright Shining Moment” give you the sick feeling of a bad dream you keep having over and over again, as in the video clip of a Pentagon press conference in which a young Donald Rumsfeld hovers in the background, his slicked-down hairdo immediately recognizable. While it’s unwise to view the parallel between that Asian conflict and the current one too literally, it’s also impossible to resist the notion that on the psychological and mythological levels the right and left are still fighting the same old war.

Indeed, Vittoria makes a strong case that McGovern was one of the 20th century’s true political visionaries, as well as one of its paradoxes. By 1965, he had been banned from entering LBJ’s White House and was viewed by members of both parties as a Red-friendly loose cannon (paving the way, one might say, for what came later). Yet the voters of South Dakota, then as now one of the most conservative states in the nation, elected him to Congress twice and the Senate three times.

If Vittoria does a splendid job of placing McGovern’s career as a moral statesman in its fuller historical context, the crucial events of his earthshaking 1972 campaign go rushing past in something of a blur. If anything, there’s too much historical context, although it’s admittedly difficult to know where to draw the line. Can you understand McGovern’s emergence without understanding the dimensions of the Vietnam quagmire or the nearly total anarchy and chaos of 1968? Probably not, so we briefly glimpse the My Lai massacre; the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy; the catastrophic Democratic Convention in Chicago; and the cliffhanger election between Richard Nixon, Hubert Humphrey and George Wallace, each a subject worth its own movie.

But the genuinely paradoxical character of McGovern’s revolution seems to elude Vittoria, who is focused almost exclusively on a glowing portrayal of the man and his moment. Yes, the McGovern campaign was a triumph for small-“d” democracy; under his banner the antiwar movement came into electoral politics, sweeping aside much of the sclerotic Democratic machinery, the cigar-chomping backroom boys of Richard Daley’s and George Meany’s generation. Yes, despite the caricatures McGovern was admirably qualified to be president — although the thought exercise of actually imagining him in the White House is almost impossible.

There can also be little doubt that the 1972 Democratic Convention in Miami Beach, with its blue jeans, long hair, dashikis and Afros, its fractious floor fights and its undisciplined schedule, scared the hell out of many white heartland Americans. As a small boy in the California mountains, watching on my dad’s JCPenney black-and-white TV, I found it a thrilling spectacle. I thought that’s what grown-up politics was like, and I’ve been disappointed ever since. But that reaction, apparently, was not universal.

As former baseball pitcher (and McGovern delegate) Jim Bouton says in the film, Miami Beach was the last totally unscripted political convention. McGovern’s acceptance speech was the oratorical triumph of his career, a tear-jerking patriotic paean titled “Come Home America” (i.e., come home from Vietnam, and come home from bigotry, racism and heartless greed). He delivered it at 2:30 a.m. Eastern Time — as someone notes ruefully, it was prime time in Guam.

On a smaller scale, the question of why McGovern lost so badly (Nixon won more than 60 percent of the vote and every state except Massachusetts and the District of Columbia) is easy to answer. The convention snafu marked a transition from a grass-roots insurgency to a grossly unprepared national campaign. McGovern’s initial running mate, Missouri Sen. Thomas Eagleton, had an undisclosed history of mental health problems and was forced to quit. George Wallace left the race after being shot, meaning there was no segregationist third-party candidate to draw Southern votes away from Nixon. Large sections of the Democratic Party establishment, including the labor movement, Southern politicians and Cold War hawks (among them many of today’s neoconservatives) defected to the Republicans, some never to return.

But on a larger and perhaps more important question, Vittoria’s film is silent: Why didn’t George McGovern become the Barry Goldwater of the left? In 1964, Goldwater’s campaign had followed much the same script, going from a populist insurrection of true believers to an electoral disaster. But Goldwater’s followers did not scatter after their defeat; they consolidated their control of the Republican Party, went to work on school boards, city councils and state legislatures, and laid the groundwork for a generation of conservative hegemony over Congress and the White House. Could the McGovern left have done the same thing?

It’s a question historians may still puzzle over in 50 years, or 100. Mr. C’s answer, I imagine, is no: Progressives of 1972 were too fragmented by identity politics, too narrowly focused on feminism or gay rights or affirmative action or environmentalism to forge a pragmatic political movement after McGovern’s crushing defeat. Furthermore, the argument continues, the ground wasn’t ready: Goldwater’s revolution addressed the reactionary yearnings of a huge “silent majority” who felt alienated from both parties and the political process; McGovern’s maxed out at a smaller number of students, feminists, African-Americans and bicoastal intellectuals.

That all sounds plausible, but it may be too easy. History teaches us that at any major turning point, different outcomes are always possible, and that revolutionaries make their own reality. It also shows that — in contrast to the Republican example — the centrist Democratic establishment reclaimed most of its power after 1972, purging leftists and declaring McGovern and his movement anathema. One can argue about the results, but the party hasn’t exactly been going gangbusters since that counterrevolution. If you subtract the effects of Nixon’s resignation on the 1976 election and the third-party candidacy of Ross Perot in 1992, it isn’t clear that any Democrat since Lyndon Johnson would have been elected president.

McGovern’s name has become a dirty word in American politics — it was used to smear Howard Dean during the 2004 campaign — but the man himself has enjoyed a distinguished humanitarian career since leaving the Senate in 1981. Today, at age 83, he serves as the United Nations’ global ambassador on hunger. Vittoria’s film is packaged in shrill and overly narrow left-wing rhetoric that makes no effort to cross ideological boundaries, and that’s a shame. Both in the film and in life, George McGovern is a bigger man than that. As comedian Dick Gregory observes in the film, when the long lens of history finally focuses on McGovern’s contentious era, he’ll appear in the main text, named as a prophet, while Nixon will be a twisted king consigned to the footnotes.