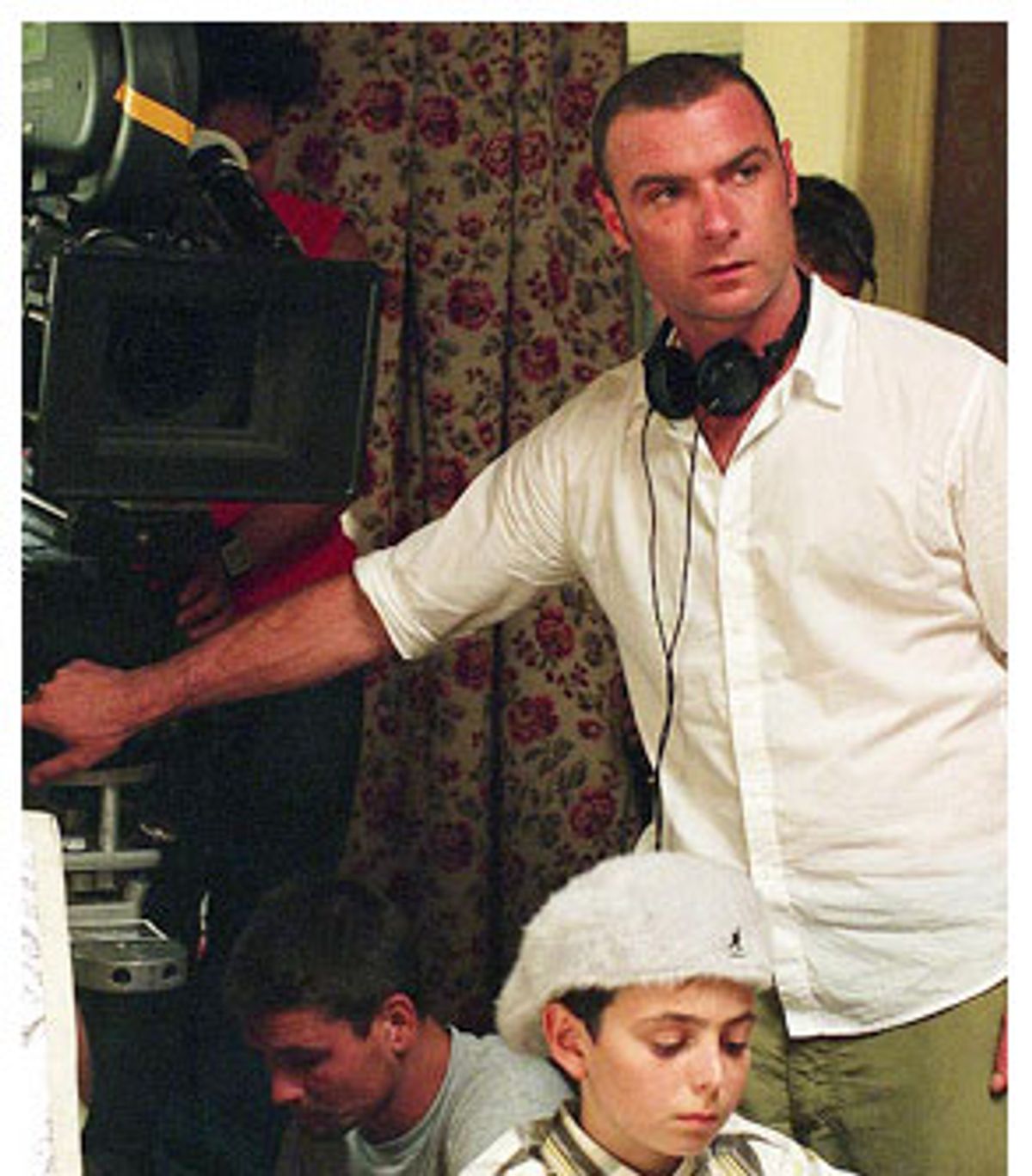

Liev Schreiber, 37, is among the most respected actors of his generation, with major roles on stage (he recently finished a run as Richard Roma in the Broadway production of "Glengarry Glen Ross," for which he won a Tony) and screen, where he's had savvy supporting roles in big movies such as "The Manchurian Candidate" (2004) and the "Scream" series, and memorable parts in a body of highly regarded smaller films, including "A Walk on the Moon" (1999), "Walking and Talking" (1996), "The Daytrippers" (1996) and "Party Girl" (1995).

But it wasn't until he became a director, Schreiber says, that he started caring about the critics. When I met to talk with him recently in New York, he noticed a local paper as we sat down.

"Oh, it's a review," he said darkly, and tossed it out of the way. "I never took things personally as an actor," he said. "I never took things personally at all, not until I started doing this."

"This" is his directorial debut, the film version of Jonathan Safran Foer's bestselling novel "Everything Is Illuminated." Schreiber's adaptation, which opened Friday, involves an American kid named Jonathan Safran Foer (Elijah Wood) who travels to the Ukraine to find his grandfather's hometown and the mysterious woman who saved his life during the Holocaust. A local, Alex (Eugene Hutz), and his own grandfather (Boris Leskin) shuttle Jonathan around the country, acting, respectively, as translator and driver. For the record, their dog (or, in the movie's parlance, their "officious seeing-eye bitch") is named Sammy Davis Jr. Jr. Part of the charm of both the novel and the film is Alex's bizarre English: "I am dubbed Alex," he says, and that his grandfather found Sammy Davis Jr. Jr. at "the home for forgetful dogs."

But beneath the story's giddy humor is a serious meditation on culture, identity and memory -- issues that, Schreiber says, he has personally been grappling with.

How did you end up choosing to adapt "Everything Is Illuminated" for your directorial debut?

My grandfather is an Eastern European immigrant from the Ukraine, and I was very, very close to him, and when he died in 1993 I started to write a lot about him, and eventually I began to develop the idea for a screenplay that was a story about an American who goes back to the Ukraine to find out about his heritage. And the structure of it was a road movie about a guy who gets involved with the mob, falls in love with a prostitute, and they rip him off and he ends up penniless, and that ultimately is what he decides it is to be Ukrainian. So I'm working on this piece and everything is going fine, and ... [the New Yorker publishes] a short story submitted by a guy named Jonathan Safran Foer, and it was called "The Very Rigid Search." It was a story about a road trip of a young man who goes to the Ukraine to find out about his heritage, and particularly his grandfather. And I was kind of blown away by the similarities between our two stories, and I guess what I was most impressed with, which was not as present in my own work, was his definitively Eastern European Jewish survivor sort of humor.

I met [Foer] and we talked about our grandfathers and talked about short-term memory and Eastern European culture ... and by the end of the night he agreed to let me adapt his short story, on the condition that I read the novel. He gave me the galleys that night, because the novel was unpublished. And I read the novel and was completely blown away by the quality of his writing, for such a young man to write with such maturity and humor and pathos. And basically it had the structure in place of a road movie, so it was just really a question of mining the novel I had read for the material I felt would be evocative in my structure. I finished the script a month and a half later; a week after that the book was published, and I opened the New York Times and there it was on the cover of the New York Times Book Review. And I realized that I was in for a ride.

So as the novel became clearly popular, did it make things easier for you in terms of getting the film off the ground?

It was a double-edged sword. On one side it made it very easy to set up a deal. Here I was the accidental owner of a very valuable property. And the novel just seemed to grow and grow and grow in popularity. And that made my job easier in terms of setting up the deal. Of course it increased exponentially the pressure and anxiety I felt about adapting a novel that was so beloved by the public.

But also people do have very strong feelings about that book and about Foer himself -- they either love him or they hate him.

Yes. I think the biggest anxiety for me in making this film -- and it only got exponentially worse as the book became more and more popular and more people read it -- but probably the biggest anxiety was the sense of responsibility I felt not only to Jonathan as a writer, but to my own family, because it's a story that's personally evocative for them, and of course for Jonathan's family as well. And that was crippling sometimes, that sense of responsibility and anxiety.

That's the nature of film: On one side of the coin it's a pragmatic, brutal kind of physical endeavor -- make the day, finish on time, do it with the money you've been allotted. And that's the reality of your day -- shoot the scene, pray it doesn't rain, hope that everything works, try to create an environment in which the actors can do their thing and still deliver the visual text that you're trying to deliver. You want to be almost emotionless to fulfill that, because it really is like a triathlon. And the more emotion and the more anxiety you feel the harder it is to get through the day. And when something doesn't go right, or if you think you haven't got it, to get caught up in the emotionality of "Christ, what's this going to do to my family? What's this going to do to Jonathan's family? What's this going to do to Jonathan and me?" -- that slows you down, stops you, and you just need to keep moving forward, and that was the hardest part.

My emotional responses to things as an actor are very useful, but as a director sometimes not so much.

Did you consult with Foer when writing the screenplay, or did he pretty much just leave you to it?

He read every draft of the script that I wrote. I wanted him to write it with me. I love his writing, he has a truly unique sense of humor, and I had some of that from my own grandfather and it was built into me somewhere, but I just knew there were riches in Jonathan's brain that I wanted. But he felt pretty adamant that he had done his part, which was the book. But we spent an awful lot of time, before I started, talking about what kind of movies we liked, what kind of things we liked, and we talked about that cultural sense of humor and what it meant in a deeper context. He had been in Europe working on his second novel, and I had been living in Europe as an actor, and we talked a lot about stereotypes and clichés of the American character that we felt were hurtful to us, and part of what we both liked about "Illuminated" so much is that it offered up a different kind of American character, a vulnerable American character, someone who has flaws, someone who was open, someone who was awkward, and more importantly than anything, someone who was looking for his own heritage beyond the borders of his own country.

It seems like it's much harder to win respect for a movie that's based on a book, because everyone's going to compare it to the book, and usually unfavorably. But in this case, I felt like the actors really looked and sounded like my idea of them in the novel. I've always thought of Jonathan Safran Foer as somewhat Elijah Wood-ish.

Good, I hope you write that, because I'm very proud of Elijah, and Elijah took a great risk to play this part. It's a hard part because it's such a stoic character, and it's so emotionless, at least at the beginning of the film. And part of the idea was to have somebody who was in a sense an empty vessel that would be filled with information over the course of the journey and then begin to emote. The characters are so vivid, and that's Jonathan's talent.

... Part of what makes a good film to me is when I'm transported to some place, and it seems like we had a really unique opportunity here with the Ukraine to take our audience to a place that was unfamiliar to them, which is in a sense what we were doing through our central character, Jonathan. I felt that it was very important that the culture and the characters and the location be as authentic as possible. That and the use of the Russian language -- as difficult an idea as that is to deal with, because nobody seems to like subtitled movies these days -- it was very important that we were being immersed in a foreign environment and that it was just as strange for us as it was for Jonathan. And to that end, there was no way I was going to use American actors who had to learn Ukrainian or Ukrainian dialects to play these characters.

The movie has nothing if not a deep sense of culture; it's about a cultural clash between East and West. I was trying to make the film feel more like an Eastern European film than an American film so that we could come down on their side, perhaps -- start on our side, and come down on their side. It's that kind of compassion that I think is evocative of the novel; you get a sense of a really broad sense of humor but at the same time you identify with them as not being really that different from us. And I think that was a real gift from Jonathan as a writer.

I wonder if your experience making remakes -- "Hamlet" (2000), "Glengarry Glen Ross," "The Manchurian Candidate" -- may have come in handy with adapting a written work to film. I mean, in both cases, you're dealing with work that has had a previous life -- with the films and plays, other actors who have played these roles, and with the book, there's the reader's idea of what the characters look like.

Ah, you jumped on the remake thing, didn't you?

Yes, I did!

Nice one! You know, approaching a story that's been done before, you don't do anything differently. The reality is that I don't know a story that hasn't been told before. How famous they are, how much people identify with them, that's something else. But I think that's the point of good stories, they have a way of repeating themselves. And if you are sincere about it, if you are personal, in other words you include yourself in the process, chances are other people will feel included because other people identify with you a lot more than you think they do. It's only when you try to be them, when you try to second-guess how they feel, that you risk missing the mark more often.

Sure, but you still have to make these things your own, and you do seem to have a large amount of experience with that. So how do you specifically do it?

Well, for instance, I have a pathological memory problem, I always have, and I've been to doctors about it because it got really serious. At one point I was upstate at my house with my brother, and the telephone rang, and I had no idea where I was. I didn't even recognize my brother. I walked in the house, and by the time I picked up the phone I knew where I was. So I started going to doctors, I had CAT scans and MRIs, they checked me from head to foot and said there's nothing wrong with you. And it had happened to me months before when I was in high school, when I was playing football, and I thought it was a concussion. After a play I was lying in the field and thinking, where the hell am I? And after about 30 seconds I was back. They said to me, maybe you should go to therapy. So I went and after talking to this therapist for a period of three months, basically I came away with the conclusion that I just have a terrible memory! I don't remember my childhood, I don't remember a lot of things, I have flashes of things, but talking to my friends I've found that this isn't so uncommon.

So for me -- now I'm trying to get back to your question -- for me, if you believe a human being is a collage or a collection of memory and history, if that's part of what makes up our personalities and who we are, then you start to freak out a little bit that if you don't have a memory then you get a bit of an identity crisis. Which is OK if you're an actor, because every month you get a new script. But when my grandfather died in 1993, I started to panic a little bit that I was losing things that were important to me. And I remember when I turned 34 I looked in the mirror and thought my hair was thinning, and you know how you get your hair from your mother's father?

Yes.

So I was thinking, was my grandfather bald when he died? And it flipped me out that the person I was closest to in the world, I couldn't remember if he had a bald spot when he died. And that was the beginning of the process of me writing about him, and that was the beginning of me being very concerned about my memory, and I started to collect things that would remind me of places and people. When I started to work on the movie, I had my assistant take Polaroids of the entire crew, and I would write their names on them because literally in a day I would forget everyone's name. So that was an element I gave to Jonathan, collecting things and putting them in Ziplock bags and creating this collage of artificial memory. And I think what moved me so much about the novel was that Jonathan was proposing, I felt, or what I interpreted because my big issue is memory, that a past lovingly imagined is as valuable as a past accurately recalled. And that was how I, as a writer and as a director, put my thing in the film.

In terms of acting, an example for me would be Eugene [Hutz], who I think is a fantastic natural performer, incredibly charismatic -- but Eugene's the frontman to a gypsy punk band, Gogol Bordello, and Eugene's used to playing to 800 to 1,000 people, and his favorite actor is Charles Bronson. So Eugene, having never acted before in front of a camera, had all these ideas of what acting was, and the whole journey for me with Eugene was getting him to accept that he was Alex, and he didn't need to play Alex, he didn't need to go to the Yale School of Drama, all he needed to do was to trust who he was and how he would react to things. And then it was just a question of scale -- you're not playing to 800 people, you're playing to a camera that is 6 inches in front of your face. And once we had that he started to blossom. It was the same thing for every character. Your personal story, which no one knows, is what people are going to identify with. That emotion comes through on camera.

The humor in the book version of "Illuminated" is largely in the language -- the goings-on are intensely serious, but then you have this comic voice narrating them. That type of voice-driven story usually adapts terribly to screen, but I liked that you retained lot of the humor by not only having Alex's voice-over narration, but also by transferring much of the quirkiness into the visual language of the film. For example, in contrasting the old and new Ukraine, you have a scene in which we see two old people sitting on a bench, but then the camera pans up and in the park behind them are all these young skateboarders. I'm sure there must have been directors who influenced those scenes.

I'm glad you noticed that. That was a big deal to me. I drew a lot of [those scenes] from the book, but I also drew a lot of them from my own investigations about culture. I started thinking about making this movie in the fall of 2001, and one of the things I was thinking of was that right after September 11, there was this window of compassion that I felt in this country. Remember when all the people were out on the Westside Highway with the signs? For the first time I felt there was an American identity, a sense of national pride. And I thought, well shit, what does it mean to be American? And because I was working on "Illuminated" I was thinking that, in a sense, this is a country of grandchildren. Then this flag waving started to happen that I thought interrupted this sense of national pride that I was feeling.

I was very happy that we were working on Jonathan's book because I felt like here was a way that we could embrace culture and in a way that would be bridging cultural gaps and reaching out internationally. So for me it was important to find ways to illustrate that culture effectively. And I guess the models I had in Eastern Europe, because I had never been there before were [Nikita] Mikhalkov, Milos Forman, [Emir] Kusturica, and there was a visual text that I had been learning since I was a kid -- what is culture visually to you? You can find examples and metaphors in the buildings, in the landscapes, in the color of people's teeth, in their fingernails, in their hair. What was so beautiful about Jonathan's book to me was here was a young person who was interested in old people, which is so rare nowadays. So for me that dialectic of old and new was really powerful, seeing old people and new people together, and old buildings and new buildings. The regrowth. I love that set we found in an old cement factory, where out of the rubble was growing grass and trees, straight out of the building. It's those kinds of things that articulate a sense of regrowth and rebirth.

Shares