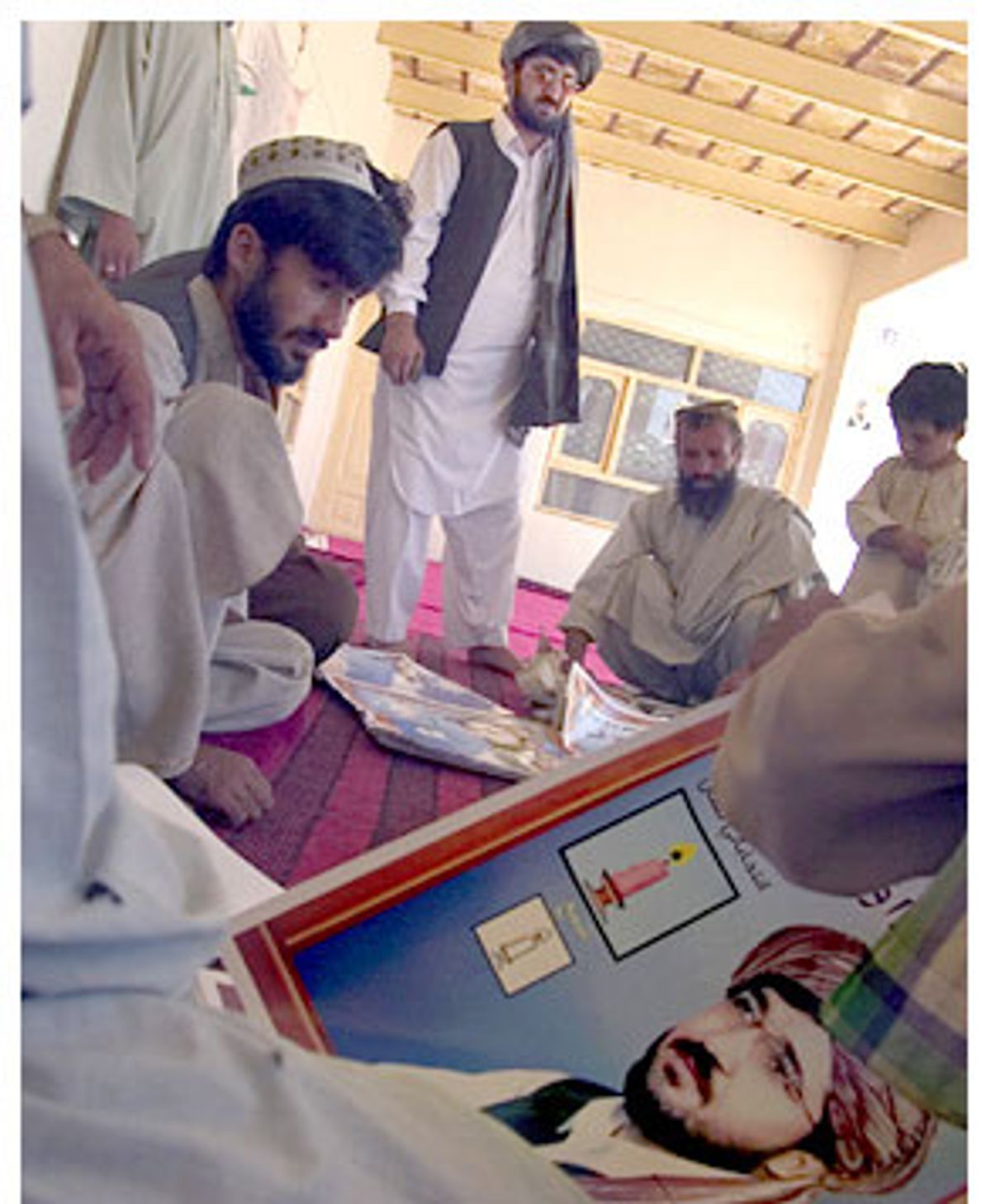

Fat for an Afghan, Mullah Salaam Rocketi is actually pretty nimble as he enters the room, tosses his turban to the side and plops on the floor. He starts popping grapes in his mouth before he speaks.

A former Taliban commander turned candidate for parliament in the restive southern district of Zabul, Rocketi explains why the American invasion of Afghanistan has yet to turn as nasty as the Soviet invasion and occupation in the 1980s. Rocketi says that most of the Pashtun tribes in the south and the east of the country -- who formed the backbone of the Taliban movement that swept to power in the early 1990s -- do not support the neo-Taliban insurgents who have killed more than 70 U.S. troops this year, making 2005 the bloodiest year for the U.S. since the 2001 invasion.

"Most of the Taliban [still fighting] had their own government regimes and power and lost them to the American invasion," he says. "So they want to fight to get the power back but they get no support from the people because [when they were in power] they acted too hard and selfish. They also killed many innocent people, so the people, they hate them."

He pauses for a moment and smiles. "But [the Taliban] are stronger than one year ago because they are supported by Pakistan," he declares.

It has been four years since the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks on New York City and Washington prompted an American invasion and occupation of Afghanistan to destroy the Taliban and the al-Qaida terror network it harbored. But despite last year's presidential election of Hamid Karzai and Sunday's apparently successful parliamentary elections, huge problems remain. Al-Qaida commander Osama bin Laden and Taliban leader Mullah Omar remain at large. There is increasing violence, not just by the Taliban insurgents but also by criminal groups. Drug cultivation and trafficking, often supported by corrupt government officials, are skyrocketing. Powerful warlords limit the writ of the Karzai regime, which has not dared to confront them; some of those warlords, who helped tear the country apart, may soon be elected governmental officials. And many ordinary Afghans resent international aid groups, which they see as wasteful, ineffective and cut off from the people they are supposedly helping.

These problems threaten what had the potential to be an international success story. The stakes are high: If the international effort here fails, Afghanistan could again become a haven for radical Islamist groups and a center of narco-terrorism. With Iraq a mess, the U.S. and the West would be ill-prepared to deal with a failed Afghanistan as well.

In a five-week investigation spanning much of the country, Salon researched the status of the military campaign against the Taliban, as well as the political and economic development of a country tied for seventh poorest in the world with an average per capita income of $800 a year. While there have been small steps toward stability, including a decent security situation in the capital of Kabul and other major cities, the attention paid to fighting the Taliban and holding a relatively credible and safe election has overshadowed major problems bubbling below the surface of this fragile peace.

The upsurge in attacks against U.S. and coalition troops has thrust the Taliban situation back into the spotlight. Representing about half the country, ethnic Pashtuns formed the backbone of the Taliban, just as ethnic Tajiks, Uzbeks and Shiite Hazara (led by Ahmed Shah Massoud, the legendary commander slain by al-Qaida agents just two days before 9/11) resisted them after they swept to power in most of the country. While the Taliban's neo-fundamentalism and almost literal interpretation of Islamic law alarmed the West, the civil war was not a battle between Pashtun fundamentalism and Tajik moderation. Rather it was a tribal fight for control of the country, as many Afghans of all stripes had become tired of the lawlessness and gangsterism of many of the old anti-Soviet jihad commanders who ran the country into the ground after the fall of the communist-backed regime in the early 1990s. Many commanders, of all ethnicities, were too busy fighting each other for control of lucrative trade routes -- and killing tens of thousands of civilians in the crossfire -- to pay attention to an austere bunch of villagers backed by Pakistan, and later al-Qaida, and dedicated to ridding Afghanistan of the jihad commanders' corrupt and brutal behavior.

But of course the Taliban, while able to provide a little more security, proved intent on imposing harsh Pashtun control over the entire country and became just as guilty of cruel and arbitrary governance. Moreover, they allowed a bunch of Pakistani and Arab terrorists to help run things, and regardless of religion or motivation, Afghans really hate foreigners telling them what to do. So most Afghans have seemed fine with their post-9/11 removal.

Despite the rise in the American body count for 2005, most Afghans familiar with the situation consider the neo-Taliban fighters to be less Pashtuns engaged in a grass-roots revolt against American occupation -- the equivalent of the largely Iraqi, Baathist resistance in Iraq -- than a bunch of creepy religious extremists backed by intelligence elements in neighboring Pakistan.

An Afghan intelligence commander, a former Talib whom Karzai persuaded to join the new government, agrees with Rocketi's assessment that the Taliban is unpopular, even in areas where it has some operational ability. He asked that his name not be used, as he is not cleared to talk to the media and does not like to advertise either his past as a Talib commander or his present as a general helping lead the fight against them.

"For the moment there are several groups fighting under the name of 'Taliban,' including Hizb al-Islamiya led by Gulibran Hekmaytar [a famous anti-Soviet jihad leader and the single biggest recipient of U.S. military aid during that fight]," he says. "There are also several groups in the provinces and the main group of them is backed by the ISI [Pakistani intelligence]."

"When there is a 'Taliban' attack near Kabul it is usually Hizb terrorists," he adds. "All of these groups are fairly weak despite Pakistan's support, so they cannot fight the [Afghan National Army] or Americans, so they must resort to terror tactics."

In stark contrast to its failure in dealing with the Iraq insurgency, the U.S. occupation in Afghanistan has done a much better job of fighting this threat. This is at least partly because NATO's International Stabilization Force (ISAF), which most Afghans see as an international effort and not a foreign occupier, patrols much of the country. (This suggests that if the Bush administration had been prepared to wait for U.N. support before launching its invasion, things could have turned out very differently in Iraq.)

"You see jeeps from Germany, France, Italy, not just the U.S., on the streets of Kabul and other cities, so Afghans like them," says Ajmal, a 27-year-old guesthouse owner and occasional translator for international media outlets. "Afghans wish they would do more security but we like them, we call them 'International Shopping in Afghanistan for Foreigners' because they are always buying things and don't seem like real soldiers," he jokes.

Rocketi, who is nicknamed for his legendary ability to operate rocket launchers during the fight against the Soviets, says that while some people get tired of the heavy-handed tactics of the American military in contested provinces like his in Zabul, the people know it is better than the alternative waiting for them in the mountains.

"The Americans have done a good job and if they were not here, my former comrades would burn me in oil," he says with a smile that belies his concern. "The Americans are not why they are fighting; they fight because Pakistan told them to win back their country."

The intelligence commander in Kabul agrees. "When the Taliban fell, most escaped to Pakistan and were given places to live and train and were told by the ISI, 'We will support you so you can go back to Afghanistan and get back your country,'" he says. "My intelligence shows that Pakistan tells the Taliban and other extremists, 'Now you will go to Afghanistan to fight, or we will turn you in to the Americans as al-Qaida members.'"

Afghan intelligence experts, law enforcement officials and Western security sources cite several reasons for Pakistan's alleged support for the Taliban. (Pakistan has vehemently denied backing the Taliban.) First, elements in the Pakistan regime have decided that having a population of dangerous militants at home is less preferable to having them walk over the mountains to be killed by American forces. Second, Pakistan is using Afghanistan to provide strategic depth against Pakistan's archenemy, India. As the intelligence commander also notes, a stable and democratic Afghanistan is a threat to Pakistan since the Afghan people have a warm relationship with India. Pakistani militants also use Afghanistan as a training ground before being sent to fight against Indian forces in the disputed territory of Kashmir.

Afghan and Western intelligence sources report evidence that the Iraqi resistance is sharing expertise with the Taliban fighters, using al-Qaida channels. This is likely to include more sophisticated roadside bombs and better information on U.S. tactics and capabilities.

A few dozen kilometers north of Kabul, a former Talib says that the fight against the Americans is legitimate. Mullah Kudus was once a spiritual and military leader of the Taliban and before that in the anti-Soviet jihad. Now he works a farm on the Shamali Plain, which lies at the foot of the Hindu Kush mountains and served as the front line during every Afghan war since 1979.

"This government obliges people to fight against them for being servants of America," he says. "These Afghans have to say yes to anything America says."

Despite his résumé as a Talib of some note -- "If I return to my town of Spin Boldak, the Americans will arrest me," he brags -- Mullah Kudus grew disenchanted with the movement after Pakistanis and Arabs linked to al-Qaida took control of it. But he hates the Karzai government and laughs at the reconstruction effort, which he sees as a spark that could ignite a new jihad.

"As you can see yourself there are huge numbers of people without jobs," he says. "The world community promised to help, but show me one factory they built here. Many of these [Afghan U.N. or NGO] workers had jobs in other countries or the companies and agencies are bringing in workers from Pakistan to work. These are not jobs open to our people."

Mullah Kudus disagrees with the current insurgency because he thinks the time is not yet ripe, that the Afghan people have not realized that the international aid effort is a sham.

"We are waiting for the people because they need to know what is happening," he explains. "The mujahedin [holy warriors] have to raise this issue themselves because people do not understand the reality. But if we fight, people will blame us, so we wait for the people to call for jihad first."

Although he does not threaten future rebellion, former planning minister Ramazan Bashardost makes many of the same points. Fired last year for unilaterally shutting down all international aid organizations and NGOs without checking with his boss, President Hamid Karzai, Bashardost is running for parliament on a platform of reform, not just for Afghanistan, but also for the international community.

"The NGOs, the U.N., and the large staff at the British, American, Japanese, French embassies has made a Mafia system of aid that lacks any transparency," he says while sitting in a campaign tent set up in a Kabul park.

Outside a dozen men and boys watch a television playing a speech by Bashardost, while the man himself greets guests and visitors in the tent.

"The Afghan people, the Afghan government, the donor countries, none of them know how the international community is spending their money here," he says. "This system works against the interest of the U.S. and Japanese people (and other donor countries) and against the interests of the Afghan people."

Bashardost argues that many NGOs are used for reconstruction efforts that would be best left to the Afghan private sector. He also notes a phenomenon that takes about five minutes in Kabul to notice. The international community -- thousands of embassy personnel, aid workers, private contractors and U.N. staff -- has almost no interaction with ordinary Afghans outside of their own limited local staff. Dozens of huge, white SUVs jam intersections, filled with armed security and covered in an alphabet soup of acronyms. "Why is it the international community in Kabul lives in luxurious guesthouses?" asks Bashardost. "They live like kings here and Afghans cannot even visit their offices -- but an NGO in Europe, where do they live? Near the poor people they are helping."

According to a Western analyst, the United Nations staff and some larger NGOs are all but barred for security reasons from interacting with Afghans not lucky enough to have jobs with them. They cannot ride in local taxis, eat in Afghan-run restaurants or shop in the many shops begging for foreign money. Most international organizations allow their employees to eat out in a handful of restaurants that not only cater to Western aid workers and journalists but actively bar entrance by locals.

How legitimate are these security concerns? There have been some attacks on international aid workers, including killings and a recent kidnapping. (These attacks were blamed on the Taliban, but were more likely carried out by warlords trying to weaken the government or settling business scores.) But all the major cities are reasonably safe. There is some crime in Kabul, but less than in New York. The really dangerous areas are the rural roads, plagued by bandits, and the Taliban-controlled areas where aid organizations never go.

There are also culture clashes between international workers and Afghans. Restaurants like the Elbow Room and Le Atmosphere serve cuisine that offers a half-decent imitation of high-end Western dining. Late at night these restaurants and a couple of nightclubs turn into drunken parties for aid workers, security consultants and U.N officials as they spend their per diems. According to one owner, who preferred not to be identified, the eateries and clubs can take in around $5,000 on a slow night, more than double that on weekends.

An Afghan friend of mine, a conservative Pashtun but one who's fairly comfortable around Westerners, recently asked me if it was true that the aid workers threw parties where alcohol was served and men and women danced together. Sparing him my memory of a journalist throwing back tequila shots as she danced on a table, I confirmed it was true. He commented, "This could be bloody bad. People might tolerate it for now, but when young Afghans start imitating this behavior, there could be real problems."

But isolation from the communities they are supposed to help, or cultural conflicts, isn't the biggest problem, according to Bashardost. He singles out wasteful spending without accountability. "I am not against NGOs," he says. "I am against NGO-ism. My problem is financial: How much did you receive and how much did you spend? I want to ask them why logistics account for 60 percent or more of their budget. The donors cannot go to Kandahar and see the school people said was built. They cannot check the quality of the school or the road project. I am trying to protect Afghans and the donors from this waste."

Khan Mohammed Donishgo, a journalist with the Hindu Kush News Agency, also charges that not enough aid money is reaching its intended target, the Afghan people. "Of something like $12 billion spent on aid and reconstruction in Afghanistan, it seems like 70 percent of it or more goes to the U.N. or non-Afghan NGOs," he says. "We know what happens here; a $100,000 project is awarded to an American contractor and gets subcontracted down to another contractor for $80,000 and then down again and again until it reaches the Afghans as a $20,000 project. We see it all the time."

Of course, some good is being done. There are more girls in school, in parts of the country medical care is much better, and some places have received food aid. There has also been some new economic development, although that might have come anyway. And in Kabul, international organizations hire many Afghans.

Despite these achievements, I never heard an Afghan praise the international aid effort. Afghans are angry because they see aid workers driving around in big cars, while the pace of change in their impoverished country is excruciatingly slow. The vast majority of places outside Kabul have not been significantly helped: Perhaps now a medical clinic is open within a six-hour donkey ride, where there wasn't one before.

The Afghan people's resentment of the shortcomings of the international community cannot be compared to the situation in Iraq, where many ordinary Iraqis joined the insurgency out of a combination of nationalism and outrage at the failure of the U.S. to provide services. But it is significant: Frustrated, unemployed men are dangerous in a country full of guns. Even if anger at the aid effort isn't driving people to enlist in the Taliban, it's not helping draw them away as much as it might if more cash got on the ground to Afghans.

And it is clear that the security situation is weakening.

Italian diplomat Antonio Maria Costa is aware of the problem. He told me last month that if he could, he'd "cut a lot of salaries and sell a lot of these 60,000-euro [Toyota] Land Cruisers that every international staffer seems to drive. I'd make a lot of staffers take Fiat taxis, if it were up to me." But as the executive director for the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime, he faces a far bigger problem. The single biggest threat to Afghanistan's stability is a group of sophisticated drug cartels that move about 80 percent of the world's heroin. And with a second year of bumper opium harvests, they are consolidating power in and out of the Afghan government.

"We definitely have seen an increase in violence related to drugs [as cartels] are fighting over routes and for the control of labs," Costa says. "The relation to cartels is like we have seen in Colombia. There are two, four, six, eight trafficking groups who begin to fight over one income."

The possibility that Afghanistan could become a narco-state is far more worrisome than the return of the Taliban, according to Costa, who estimates the international community will spend $500 million next year to persuade farmers to grow other crops.

"We are at the beginning of the process [of cartels] and it is one that will eventually end up in violence," he predicts.

Maj. Gen. Sayed Kamal Sadat, who heads the Counter-Narcotics Police, also worries that the drugs will destabilize the country.

"After two and a half decades of war some commanders remain armed and get drugs through gangs they control," he says. "Many of these men have connections to terrorists. It is the warlords and gangs working to destabilize the country, not for jihad but for money."

Costa is not sure the locals can handle the problem, in no small part because he finds the Afghan government to be rampant with narcotics corruption, a suspicion confirmed by narco-traffickers interviewed by Salon.

"Honestly? An efficient and independent judicial system is necessary and we don't have that yet," Costa concludes. "And government-sanctioned impunity only leads to more and more crime."

"Abdullah" (not his real name) is a 45-year-old midlevel manager for a large drug-trafficking organization active throughout the country and based in Mazar-I-Sharif. He doesn't know the exact size of his organization because it is divided into cells, but it has helped traffic "thousands of half-kilo packets of heroin into central Asia every year." And that's just his side of the operation.

The Taliban, he said, offered a good bit of protection to the trade: Traffickers could use Kabul International Airport to ship heroin but had to pay a customs tax. But the situation is far better now. With little fighting these days and an end to the seven-year drought, these past two years have set records for production and export. And the cartel has absolutely no fear of public officials or arrest.

"In this government, there are many government ministers and other people involved, not only little business people, but very big people, who control all the borders and the exports." He says his group does "not have to bother guarding our convoys because we buy everyone who can bother us." He uses a profane Afghan expression to explain: "Before you enter a house of a village elder, you pay the whole village," he says laughing. "Then [the elder will] even let you fuck his wife." As for the U.S. military presence, he shrugs. "They never bothered us even during the war and they don't bother us now."

With rumors -- in some cases later backed by arrests -- that many high-ranking officials in the current government are involved in the drug trade, as well as trafficking by warlords opposed to the Taliban, Costa says there has been a tendency by American and coalition forces involved in the hunt for al-Qaida targets to turn a blind eye to trafficking by allies.

"There is some evidence that this has been happening, but I think there has been a change in the conventional wisdom, toward the idea that a fight against drugs and poverty is also a fight against terrorism," says Costa.

Another major problem cited by Donishgo, the journalist, is Karzai's decision not to ban former warlords from the new parliament. Only a few dozen potential candidates were excluded for failing to disarm their militias. Any warlord or drug lord who bothered to try to look legitimate was allowed to run, according to Afghan and Western rights groups.

"Some warlords and drug lords are using the elections as a way to become official and are incapable of helping the people," Donishgo says. "Some people have been withdrawn, but voters all complain about candidates who have private armies."

Karzai, according to many analysts and observers, has lost credibility not just because of the perception that he is a pawn of the West, but because of his reluctance to confront warlords, who will likely become legitimate officials in the coming weeks as election returns are counted. Karzai and his backers argue that kicking powerful warlords out of public life is dangerous and could lead to new insurgents coming from the Tajiks and Uzbeks. But former planning minister Bashardost disputes this, albeit with evidence that is anecdotal.

Bashardost points to Ishmael Khan, the one-time governor of Herat province and a powerful commander who fought both the Soviets and the Taliban and is known to be ruthless and power-hungry. Khan's refusal to turn federal tariffs over to the Kabul government sparked a power struggle with Karzai earlier this year.

"[Karzai] said if we replaced Ishmael Khan, there would be a war in Herat," Bashardost says. "But I do not believe the Afghan people support these warlords. When Khan was removed there were riots for only one day and a few people attacked international community offices. That was all. The analysis of Karzai and his international advisors is wrong. If they are removed there will not be war because none of the people support them. They hate them."

Najia Hanifee, an Afghan woman working for a German NGO that helps build democratic institutions, agrees, saying that there cannot be democracy as long as the voting legitimizes the men who helped destroy the country.

"When I yell at my friend who works as an advisor to Karzai that he has let men with blood on their hands join the political process, he tries to tell me to be respectful because Karzai has brought elections. Well, Karzai didn't bring these elections, [American] B-52 [bombers] brought the elections. Karzai didn't even bring the B-52s, Osama bin Laden did!"

Shares