"No Direction Home: Bob Dylan" (which airs on PBS Monday and Tuesday) is, like the work of its subject, part fraud, part tease and part revelation, shot through with flashes of genius.

A great deal of time, care and talent went into its making, and yet it seems as sloppily made as the tossed-off albums that all but buried Dylan's reputation in the 1980s. Over the course of two installments and three and a half hours -- relentlessly focused on the first five or so years of Dylan's career -- "No Direction Home" offers little that is new and much that is already grindingly familiar to fans of His Bobness. And yet it is tremendously watchable and occasionally rewarding, even if it's apt to leave most viewers with the feeling that they have been served appetizers and dessert without getting so much as a glimpse of the main course.

Is it necessary, in the four decades since Dylan released his first album, to explain why a rock musician deserves a slot in the "American Masters" pantheon? A friend of mine recently spent a frustrating evening with a young woman who said, "Look, I know Dylan's a legend and all, but what's the big deal? Why's he important?"

The only response to such doubters is: If you value popular music as a venue for serious artistic purpose, thank Bob Dylan, who infused rock and folk music with blazing intellectual energy and visionary poetry. If you look back on the late '60s and early '70s as a lost era of pop music ambition and innovation, then thank Bob Dylan, whose 1960s albums were the benchmark that motivated artists across the pop spectrum, from the Beatles and the Rolling Stones to Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye, to stake claims for themselves as something more than purveyors of disposable junk music. And if you despair of the legions of puling singer-songwriters who followed in his wake ... well, don't blame Bob Dylan. The man can't help it if his imitators lack his outsize talent.

Recognize also that this talent came along at a fleeting, never-to-be-repeated moment when the record industry, baffled by rock music but eager to exploit its commercial potential, was still loose enough to give somebody like Dylan the space to grow, and when radio was still capable of making Dylan's 1965 breakthrough "Like a Rolling Stone" into a cultural watershed as well as a pop music landmark. Combine that with a manager, Albert Grossman, who shrewdly gave Dylan mass-market credibility by encouraging mainstream performers to release sweetened versions of his songs while preserving Dylan's own albums as pillars of harsh integrity. By the time mass-market listeners were ready to answer the challenge posed by the promoters at Columbia Records -- "Nobody sings Dylan like Dylan" -- their ears had been made ready by the likes of the Byrds and Peter, Paul and Mary. In the fragmented, highly corporatized music industry of today, there may be other artists who could match Dylan's talent, but none will ever equal his impact.

Dylan parted ways with Grossman decades ago, but the emphasis he placed on image manipulation and mystique maintenance was a constant throughout Dylan's career, and "No Direction Home" is best viewed as another addition to Dylan's hall of mirrors. Even the credits are deceptive. This is not "A Martin Scorsese Picture," except in the loosest sort of auteurist terms. As last week's Wall Street Journal made clear, "No Direction Home" is an in-house project from Bob Dylan's management team, conceived as a way to frame Dylan's legacy while the man himself is still around to supervise the work.

The rather desultory interviews with a glowing Joan Baez, a haggard Allen Ginsberg and other figures from Dylan's career were conducted not by Scorsese but by Dylan's manager and staff -- probably just as well, in light of Scorsese's fumbling attempts to interview members of the Band in "The Last Waltz" (a direct inspiration for the earnestly fatuous Marty DiBergi in "This Is Spinal Tap"). The fact that Ginsberg died in April 1997 gives an idea of how long this project has been in the works. The interviews with Dylan himself show the maestro in a disarmingly straightforward mood, offering flashes of the quiet wit and wordplay that make his recent "Chronicles" such an engrossing read.

Scorsese was brought into the project late and allowed to assemble the film only from archival materials vetted by Jeff Rosen, Dylan's manager. Scorsese's presence is most clearly felt in a moment of almost sublime goofiness -- a re-creation of Dylan's notoriously obtuse 1963 speech to the National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee, with Scorsese doing a Dylan impersonation that wouldn't pass muster at a high school talent show. He even drops the punch line, when Dylan baffled and offended the audience by claiming to feel kinship with Lee Harvey Oswald.

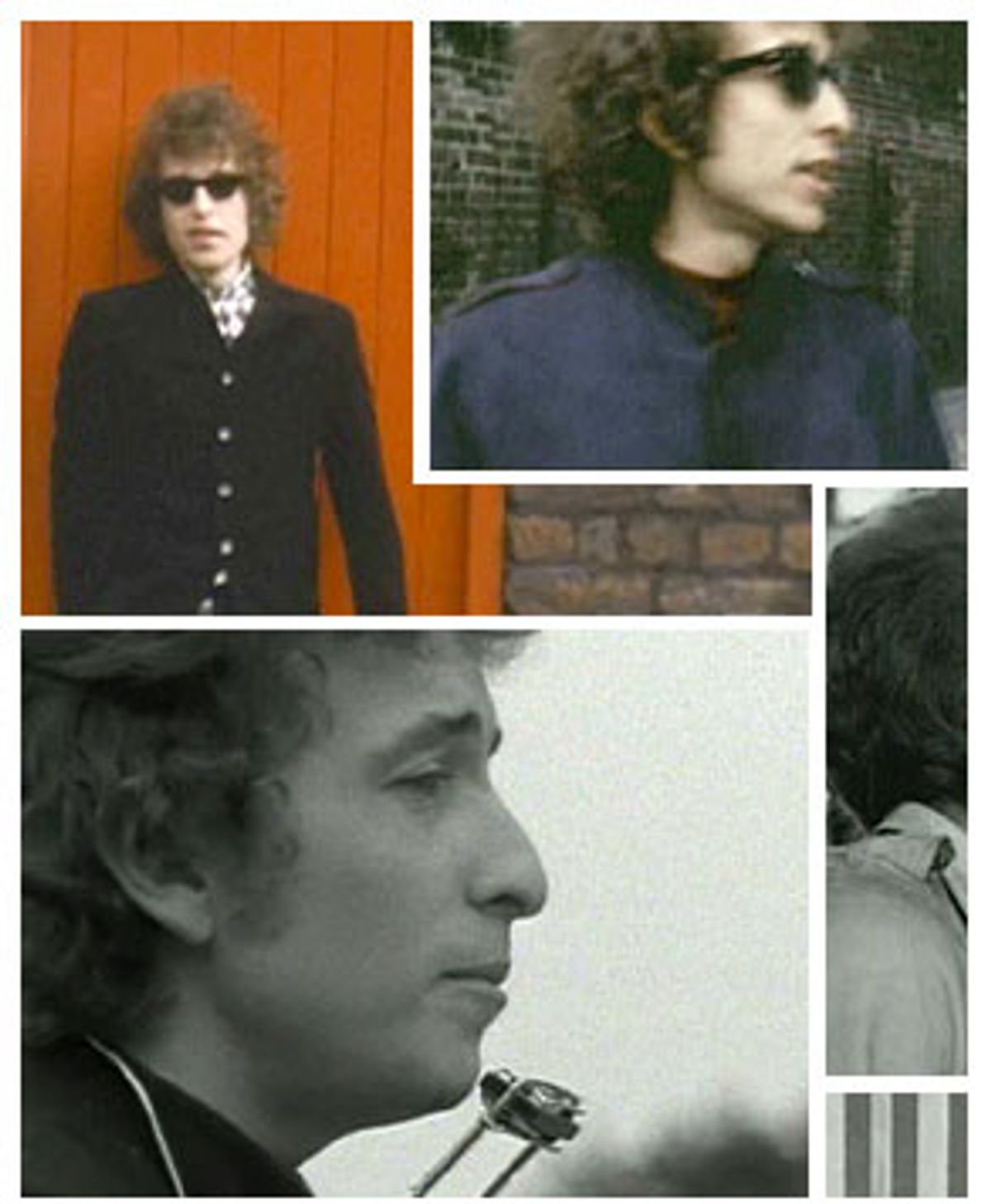

Scorsese follows a skeletal chronology of Dylan's progress from the iron hills of northern Minnesota to the folk clubs of Greenwich Village, but frequently leaps ahead to the clamorous performances of 1965 and 1966, when Dylan enraged the folkie faithful by dropping the Woody Guthrie poses and reinventing himself as a frizzy-haired rock hipster, culminating in the creation of "Like a Rolling Stone." After years of watching grainy bootlegs of "Eat the Document," the aborted documentary of Dylan's 1966 swing through England, it's great to have this footage in a clean, well-mastered form. I'm sorry to report that Scorsese doesn't include the gruesome limousine ride with John Lennon, which shows Dylan deathly ill from a combination of exhaustion and drugs while the Smart Beatle sits frozen behind his shades, clearly terrified that he might say something unhip.

It's all very watchable, but this is such familiar stuff. Heavy-breathing rock critics like Greil Marcus and Paul Williams have devised a veritable Stations of the Cross story line for this period, ending with the motorcycle accident that Dylan used to take himself off the celebrity treadmill and try his hand at something approaching a normal life. (Scorsese, curiously, omits the accident, which would at least have given "No Direction Home" a more shapely narrative.) Personally, I find the post-accident Dylan far more interesting as an artist and a human being -- given a choice between the icy hipster glaring from the cover of "Highway 61 Revisited" and the regretful, passionate husband of "Blood on the Tracks" and "Desire," I'll go for the more mature version. The magnesium-flare brilliance of "Highway 61" and its mid-1960s companions is undeniable, but it doesn't shed much warmth.

"No Direction Home" tells us nothing about Dylan we didn't already know, or thought we knew, but it could hardly have turned out otherwise, given the circumstances of its creation. "I don't know what he thought about," Baez says at one point. "I only know what he gave us." In "No Direction Home," Dylan gives us something to while away a few hours of viewing time, nothing more.

Shares