In 2002, on the eve of her 30th birthday, depressed and dreading another year as an office drone, Julie Powell decided she needed a hobby. But while knitting or yoga might have appealed to some, Powell’s tastes ran to the absurd — and perhaps the self-destructive. Sitting at her kitchen counter thumbing a well-worn copy of Julia Child’s 1961 cookbook classic, “Mastering the Art of French Cooking,” Powell had an epiphany. She would cook every one of the 524 recipes in the book. And — damn it! — she would do it in one year.

And so the Julie/Julia Project was born. For 365 days, on a Salon.com blog of the same name, Powell chronicled her adventures in aspic, her battles with live lobsters, and her catastrophes with crepes in a frank and fearless style that quickly earned her a following. With her husband, Eric, by her side as resident drink-mixer and dishwasher, and from within the tiny confines of her Long Island City, N.Y., kitchen — with cracked walls, cramped countertops and maggots (yes, maggots!) collecting under the drying rack — Powell stewed and sautéed, sliced and diced, every kind of fish and fowl imaginable.

Like the star of an Internet reality show for foodies, she kept fans rapt with stories of marital strife brought on by carb-induced crankiness, midnight trips to the market, and a disastrous Sauce Ragout. Along the way, Powell also learned to scrape and slurp the marrow from bones, to deconstruct an entire duck, to savor the smoldering taste of liver. Countless pounds of butter and botched dinners later, she realized to her surprise that she had stumbled upon a spiritual salve. That, and a lucrative book deal.

How’s that for a fairy tale ending for a secretary from Queens?

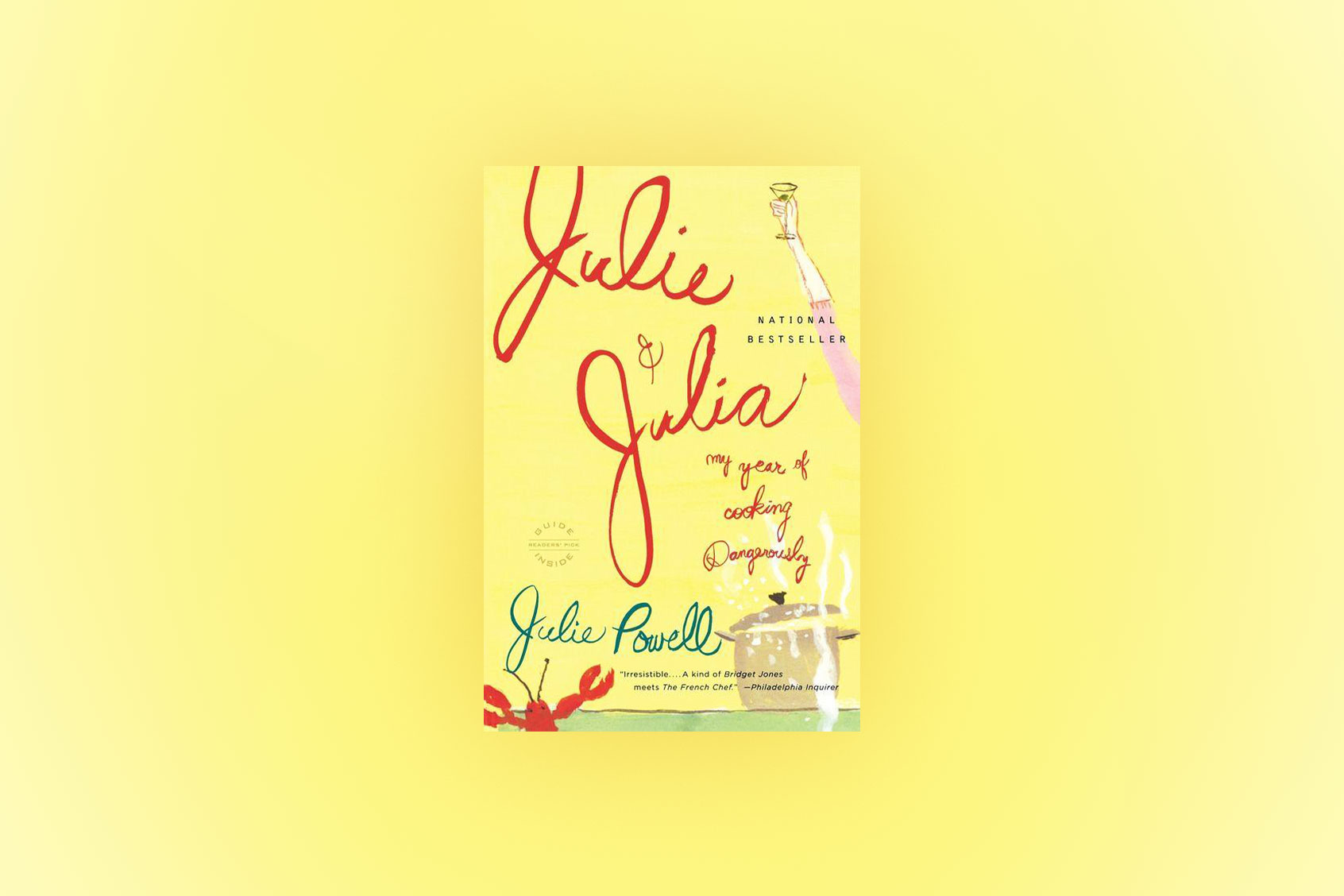

Powell, whose memoir, “Julie and Julia: 365 Days, 524 Recipes, 1 Tiny Apartment Kitchen,” was published late last month, recently sat down with Salon for lunch at New York’s Casa Mono. Over sweetbreads and Spanish olives, we discussed her dramatic good fortune, the frightening loyalty of her blog readers and her ongoing fascination with butchers.

A year and a half ago you were a miserable temp and now you have a new book deal and a steady, fairly glamorous gig as a food writer. Don’t you just hate yourself?

Life is really good — so much better now than it was a year ago. But I had this moment when I went into a bookstore and my book was already on the shelf, a full week before its release date, and it just completely freaked me out. My first reaction was like, OK, that’s done then. Maybe I don’t have a real gift for happiness, but it seems like those landmark events that are supposed to make everything great — they just don’t ever hit. There’s always that feeling that something else is going to happen down the road to make it coalesce into a great new fabulous life, and really it’s never finished. You just keep living.

Now new stresses come up and replace the old ones. The past few weeks have been hectic and I got myself overcommitted between writing articles and doing photo shoots, and at one point I found myself getting a little pissy about it. And then I wanted to just slap myself, because the worst day I have now is so much better than the best day I ever had as a temp.

So, I hear you have a thing for butchers.

Yes, actually. I really admire their skills. For a long time while I was working as a nanny in the West Village I got in the habit of going to Ottomanelli’s, a wonderful old-fashioned butcher shop, anytime I needed something special. Butchers are great because they sell you the duck, and they can also tell you how to cook it. If you go to a store, even a nice grocery shop like Whole Foods, you call them up and they have to patch you through to the resident butcher who is there three days a week until 5, and he’s the only guy who knows how to do anything. For my next book I want to train to become a butcher. My husband, Eric, of course wants me to butcher a dog in Korea and a horse in France.

Do you think people need to have a better understanding of where their food comes from?

Sort of. I did this article about ancient cuisines and I needed to find blood, because I had Mesopotamian recipes that used blood as a thickener. And I went everywhere. I went to people who raise and slaughter lambs for a living, and told them I needed blood, and they looked at me like I was fucking Dracula. I wanted to say, “You’re the one who killed them!” That got me thinking about how we have these limits based totally on our cultural circumstances. “I’ll raise and slaughter an animal, but I’m not going to eat its blood. That’s disgusting.”

In the beginning of the project, at least, your focus was on cooking. Why did you start a blog, too?

At first, the blog was supposed to serve a purely journalistic function. I was going to cook every night and then record it in the blog, and it was going to keep me honest and keep me working. But I found writing about what I was cooking every night to be extraordinarily boring. “I melted the butter” and “I browned the beef” — it quickly became very tedious. At first I tried blogging at night after cooking, but I was usually pretty drunk and tired, so I had to stop. Then I started blogging the next morning, before I had a shower, before I had coffee — and I’d write off the top my head, with no editing at all. To make matters worse, I had dial-up at the time, so I was constantly being cut off and so I just wanted to crank something out and post it before I was interrupted. The stuff about my life was just kind of squeezed in there, but it became the thing that the readers of my blog were more interested in, or at least as interested in. And the personal part made it more interesting for me, too, because the project became like the spine of my life, and everything else was built around it.

The food blogging community seems very insular. Are there any other blogs that you follow closely or admire?

I’m a terrible blogger and a terrible citizen of the blogosphere. I’m going to get in a lot of trouble, but the truth is, I actually find most food blogs really boring. I try to look at other people’s blogs and they have pretty pictures and they’re so proud — but really, I just don’t care. I don’t know anything about that person, and I don’t know why it’s important to them. Food in itself becomes just a mass of prejudices and snobbery and everyone looks like a prat when they write about food. For me, what I became more interested in was how my life began to inform my cooking and what I came into the kitchen with from my day. I don’t know if I would have ever come to that realization if I hadn’t been keeping a blog. If I’d just written in a journal, I’m not sure I would have finished, because the communal nature of the blog definitely kept me going.

I read not long ago that in the past four years, enrollment in culinary schools has increased almost 40 percent, and that the average age of the students has risen from 20 to 27. The explanation seems to be that young professionals are dropping out of careers in law and business and embracing lives in the kitchen.

There is a trendiness about food, which I guess is born out of greater access to all different cuisines and ingredients — like being able to buy sushi at the Stop & Shop. And the more our work is about sitting in front of a computer all day and feeling isolated — which, really, pretty much all work is these days — the less desirable it seems to hole yourself up in front of a typewriter or computer alone to write a book. Whereas food is a really physical thing, it engages all of your senses, and you have to move and stand up and your back hurts. There is the idea that food is community building. I cook for very selfish reasons. It just gives me pleasure. You could see it in my descriptions while I was writing the blog; when I made liver, I said it tasted like sex, like “the silky soul of steak.”

I find that cooking is actually therapeutic in the same way that sex is therapeutic, in that you’ve gotten so into your body and into your senses, that you can’t worry about the rest of the crap. You just have to let go of all that brainwork. And I think so many people, as we’re approaching 30 and don’t know where we’re going and have so many choices and we don’t know which path to take, your brain just starts to do this spin cycle and it feels like it never stops. For me, cooking made it still for a while.

With “Mastering the Art of French Cooking,” you seem to have zeroed in on a text that made you slow down in the extreme, partly because it is from a very different era.

One of the reasons “Mastering the Art” appealed to me was that it wasn’t a part of that trendy Food Network world where you always have to use the right ingredient. Instead, it’s elemental, it’s simple. It wasn’t about a trendy new cuisine. There was a lack of topicality to it, a timelessness. I had gotten sick of going to Whole Foods to get wasabi-whatever. At first I imagined I would just go to Key Foods and get some chicken and some Morton salt, and I’d be fine with those simple ingredients. [Laughs] Of course, that turned out to be wrong, but I do like the message the book brings to its audience of women, which is: This is not about shopping. It’s about taking foodstuff and making it beautiful and enjoyable.

Looking back I think one of the reasons the book really spoke to me at a gut level was that there was something about the prose. Yes, the recipes are amazing and you read them and think, “Oh my god, she says to use two sticks of butter!” — but aside from that, in the prose there is an enthusiasm that shines through, without being super-chatty. It is much more formal than that, but buried under that there was this person saying, “Look what I can do, and you can do it too, and this is so exciting.” To me it just seemed like incredible generosity. There was some reason that it was always on my shelf and I’d look at it as I was sitting around making my London broil and drinking gimlets, depressed. I would touch it and it gave me some kind of comfort.

Something that was not central to your blog but that you focus on in the book is the idea that the personal awakening that cooking stirred in you was actually parallel to one that Julia Child experienced.

My perception that there were these parallels really made me have a deep gut feeling of connection as I learned her story. Julia Child didn’t learn to cook, or even eat well, until she was older than me — she didn’t take her first cooking class until she was 36 or 37. And there is an appreciation that comes out of that. When you meet some hotshot young chef from California who was raised by hyper-conscious parents and now has opened restaurants in New York and Hollywood, even though he might be a great chef and know a ton about food, it always sounds to me as though he’s talking in sound bites.

That’s also why, though obviously the food was a big deal to me, in the end I’ve come to understand that the project and the book weren’t really about food. It could have been anything; you know, my husband is training for a marathon now, which I find to be the most excruciatingly boring thing in the world, but that comes out of a similar place. He didn’t run, he didn’t exercise, but one day he just said, “You know, I really need to do this.”

Funny you use that analogy, because it really did seem to me that the whole project was essentially an exercise in endurance. You said to yourself, I am going to go way outside the bounds of my normal existence, even if it drives me insane.

Well, it all goes back to turning 30 and having a profound sense of indecision. For years, I had temp jobs, and I would stay there for a year and they’d offer me a permanent job and then I’d run. I’d think, “Are you kidding? I’m not really going to do this.” I had this profound sense that making a choice I was going to have to stick to was like a prison sentence, a condemnation. And later, frankly, I sometimes even thought about the project that way. But at least it was my choice. Ultimately I think we get so scared that our choices are not going to lead where they need to, and we’re not going to have the right husband or the right career, that we just don’t make any choices at all. For me the idea of making my own choice and seeing it through to the end — even though there was no logical reason to do it — wound up being a freeing thing rather than a constraining thing.

Did the people around you understand what you were trying to do?

Not at first. Although my husband got it almost instantly; he actually got it before I even got it. He literally said, two days into the project, “You are going to be famous.” And I thought, “OK, sure…” But he just saw it as this wonderful opportunity, not for money really, but as an exciting project. Everyone else was some version of nonplussed. It took my mother about eight months to get over the idea that I was not mentally ill. She kept saying, “Why, why? You’re making yourself crazy, you can always stop, you’re getting fat, your skin’s bad. You should quit!” Really the blog stuff was what helped turn her around, because this support I was getting from strangers made my mom take notice. And then every once in a while, I’d get a reader who’d come to the site expecting some really fancy gourmet Julia Child food blog, and write some nasty comments, and then the rest of my loyal readers, including my mother, would jump on them.

Toward the end of the project, I’d get sick and not blog for three days and I’d get frantic notes from readers asking, “Where are you?” My friend Hannah would call me up and say, “You’ve got to post. People are freaking out.” So that was nice — a little creepy, but nice.

You attach most of your existential anxiety to your crappy dead-end job. But the fact is that you were a young woman married to her high school sweetheart and living in the outer boroughs — something that must have set you apart from a lot of your peers. Was the project also a way of getting back in touch with that world?

Absolutely. I had really cut myself off in a lot of ways. And it’s complicated, but the marriage had become what we did instead of the city. I don’t write about it so much, but it’s there underneath. We were completely devoted to one another, but there was also this feeling that I’m in my late 20s, and the marriage was just like the job — just one of a series of boxes I felt around me. I think the great thing about the project, for both me and my husband, was that it broke us out of that womb we’d built for ourselves and made us interact with each other, and friends, and even the city, in more difficult ways. I was always running all over the place looking for calves’ feet or kidneys or sending Eric out for some ingredient. We spent so much time worrying about keeping this fragile little project in place. But my husband got me though this thing. I literally could not have done it without him.

What happened when the project was done and I had the book deal, was that all of a sudden I had my own life. My life was not just about coming home to him at the end of the day and being miserable. And just like French cooking, you can’t master the art of marriage in a year, or even seven, but it’s nice that it made us engage in trying.

A lot of the comedy in the book comes from the fact that you really make your apartment seem like a hellhole. Now that you’ve gotten your big break — and a six-figure book deal — are you still living in Long Island City?

Yes, but hopefully not for long. But it’s funny how making obscene amounts of money is still not enough. Now we’ve been thinking, let’s wait for the next book to come out, and I have this movie money …

You have movie money? Oh my god, it’s worse that I thought. [Laughs]

No, I know, it’s ridiculous. I mean, we’ll see, but I do have an option.

Who’s going to play you?

I don’t know — that’s the million-dollar question. I keep arguing for Kate Winslet. I also love Catherine Keener, but she’s too old. I actually get much more excited by the idea of casting Eric. I’ve long had this idea that it should be Don Cheadle, because I have this image of Don Cheadle slumped in the doorway of my kitchen just watching me, exhausted and sympathetic.

No, they’re going to give you Steve Zahn.

Yeah, Steve Zahn, right. I did say I would take Jason Bateman, because I have a huge crush on him. I’ve always had a thing for that buttoned-up guy thing. I just want to unbutton them.