There were some things I liked about "Shopgirl," the film adaptation of Steve Martin's bestselling novella. I write those words with teeth firmly clenched, because it's basically a dreadful film that should never have been made. Actually, the things I liked can pretty much be summed up as Claire Danes, who brings her appealing, off-balance combination of gawkiness and sexual hunger to the role of Mirabelle, a young artist from Vermont lost in the diluted urban soup of Los Angeles.

Mirabelle is deliberately (I guess) presented as an oddball, a young woman in some version of the 21st century who doesn't seem to watch TV, listen to pop music or own a pair of pants. That might all be fine if "Shopgirl" presented her in some coherent social context, or possessed the aesthetic intensity to forge its own universe and make such questions irrelevant (like, say, this year's powerful British import "My Summer of Love"). But Mirabelle drifts like a ghost through a gloomy realm that looks like contemporary L.A. but is swaddled in a deadly concert-hall hush, facing horrors worse than those encountered by any splatter-movie heroine.

First she goes out with Jeremy (Jason Schwartzman of "Rushmore" fame), an assemblage of groan-inducing slacker stereotypes that Martin and director Anand Tucker apparently see as a satirical portrayal of Today's Younger Generation. Jeremy stencils logos for a company that builds amplifiers. He asks Mirabelle for her number at the laundromat, but doesn't have a pen. Or paper. He shows up to get her without cleaning the crap off the passenger seat of his old beater, then has to borrow money from her to go to the movies. A bit later in the evening, he pulls the "condom" out of his pocket only to discover that it's a mint, which he eats. OK, that bit's actually funny. But the general mode here is laborious shtick that might have felt vaguely current and halfway amusing in a Hollywood movie of 1989.

I would have been grateful, nay, delighted, to have "Shopgirl" stick to Mirabelle's tepid relationship with Jeremy, caricatured aficionado of corn chips and masturbation that he is. If, that is, we might thus have been spared Martin's terrifying performance in the sugar-daddy role of Ray Porter.

I'm not quite sure what has happened to Steve Martin; I was never his biggest fan, but some of his early movies are silly and fun and some of his mid-period ones, like "Roxanne" and "L.A. Story," are enjoyably sweet. If I were his therapist, I would no doubt applaud his desire to reinvent himself as an author of worldly-wise fiction. I haven't read "Shopgirl" and am hopeful that it's better on the page than on-screen (although Martin's snippets of voice-over narration are not encouraging: "...he had hurt them both, and he cannot justify his actions except that, well, it was life"). But his character in the film, resembling more a Madame Tussaud waxwork of Steve Martin than the real thing, crystallizes all the discomfort below the surface of "Shopgirl" and turns a dreary movie into an awful one.

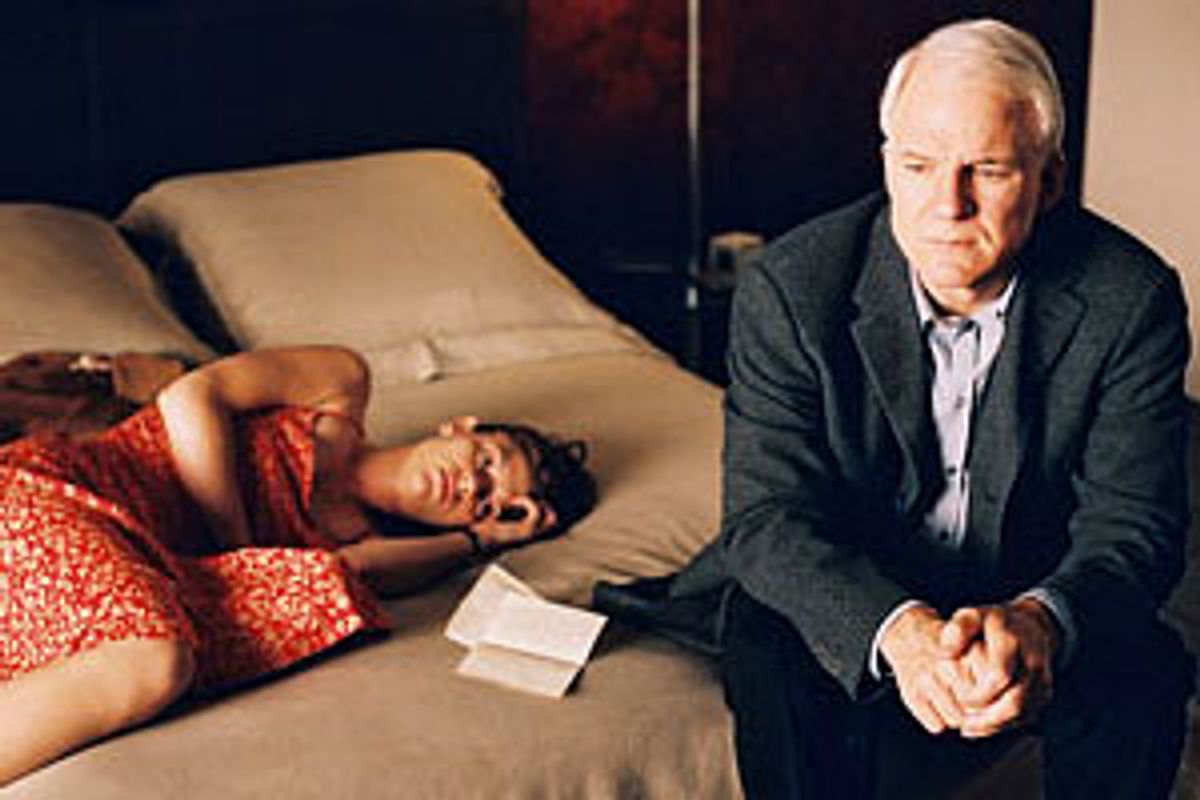

Ray is supposed to be the suave older guy with money and taste who sweeps Mirabelle from behind the glove counter at Saks (if indeed the Saks store in L.A. even sells gloves) and makes her feel appreciated, in body and spirit, for the first time. First of all, this is a trite and slightly unpleasant theme that cries out for original handling and doesn't get it here. Martin's performance is one of implacable, rubberized unhappiness; you get the feeling he saw Bill Murray in "Lost in Translation" and thought, "I can do that."

He can't, though. Is Ray a damaged divorcé who falls in love with Mirabelle, after his own fashion, but can't express his feelings? I guess that's the idea, but you can't really tell. He could also be planning to add her to his collection of chopped-up girlfriends beneath the pool. He could be a narcoleptic. He could be the reanimated corpse of Richard Nixon, nervously sweating embalming fluid. He could be shot so full of Botox it's a wonder he can speak at all.

Faced with her competing Lotharios, Mirabelle inexplicably does not flee the country or enter a convent or explore her long-suppressed interest in the lesbian leather-and-latex community. Instead, she falls in love with Dead Nixon, or whoever he is, and is heartbroken when he sleeps with an old flame. (Rebecca Pidgeon's one-minute cameo as the seductress has more life than the entire rest of the film.) Unbeknownst to her, Jeremy is on the road with some bad band in the Pearl Jam vein, reading self-help books and obsessing about her. We know that he's a changed man when he gets back because he has shaved and owns a beige Hyundai.

Good movies usually happen when director, actors and script come together in an inexpressible kismet. Truly bad movies, as opposed to mediocre or careless ones, require the same sort of chemistry. Tucker, the English director who made "Hilary and Jackie," seems to have been a marvelously wrong choice for Martin, both as actor and author. "Shopgirl" might have worked, by which I mean been halfway tolerable, as a breezy comedy that faced its own ickiness and lack of originality with a little song, a little dance, a little seltzer down the pants.

There's so little sexual chemistry between the actors in this film that it seems like a kind of accomplishment. I've seen shows on C-SPAN that were hotter than this. There's an early scene with Danes and Schwartzman in bed that's no worse than mildly embarrassing, but I sat through the film in queasy terror, awaiting the moment when the Nixon zombie might doff his clothes, expose his burnt-sienna flesh and make sweet, sweet love to his little mademoiselle. Mercifully, good taste -- or just sanity -- intervenes. But that must be why Martin looks so unhappy: He's sitting there the whole time thinking, "I'm asking the audience to sit in the dark for two hours and think about me sleeping with Claire Danes. Have I completely lost my mind?"

Tucker shrouds his scenes with piss-elegant darkness and frames them with Bergman-esque snippets of chamber music. Even the decision to use Martin as a narrator, reading bits of his New Yorker-parody prose, is bewildering: Is this Ray talking? If so, how does he know all this stuff about the other characters' inner feelings? If not, is this some arch, postmodern gesture, the god of this universe intoning from Olympus? If none of the above, why doesn't he shut up? Like the whole movie, like the damn tongue-in-cheek title, it's supposed to seem old-fashioned and muted and tasteful and true. When it's really just art decoration for an aging celebrity's unpleasant fantasy.

Shares