In a courtroom in New Jersey, lawyers are arguing about condom size.

The case is a patent-infringement suit. In the normal run of events, such cases are mind-numbingly boring. But when the product in question is a condom, and the patents at issue refer to design modifications that are supposed to increase male pleasure during the sexual act, you're not dealing with a normal legal situation. This is a case in which the technical question of how a penis is properly stimulated is of critical importance not just to the prospect of great sex but also to such momentous affairs as the fight against AIDS. Most people will likely agree: There is nothing boring about that.

We'll get back to condom size in a moment. (Suffice it to say, size matters.) For now, the basics are this: A company called Portfolio Technologies (PTI) is suing the conglomerate that owns the makers of Trojan condoms, who recently brought to market a popular condom called the Twisted Pleasure.

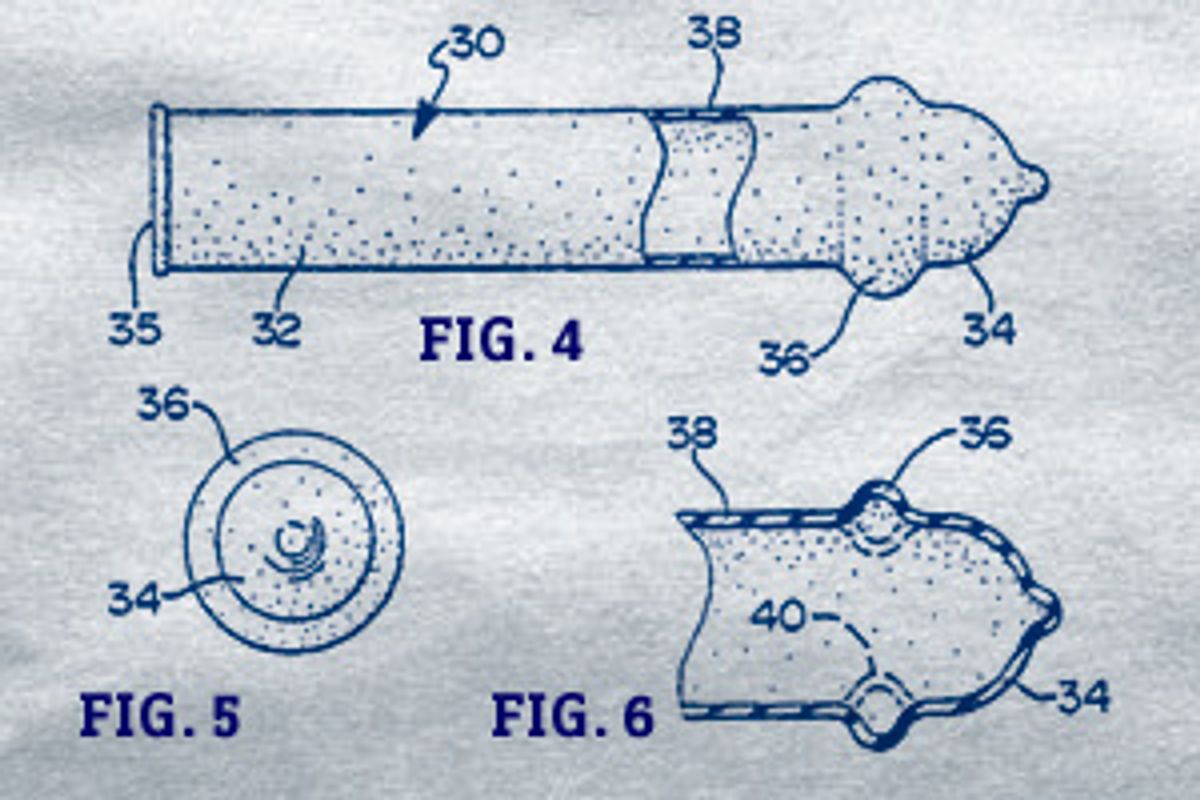

PTI owns the rights to two patents embodied in the legendary Pleasure Plus condom, a "male prophylactic device" that sent a thrill through the industry and condom aficionados with its P-shaped "pouch on pouch" design some 15 years ago. Inside a baggy pouch at the end of the condom, the Pleasure Plus included an extra dab of latex that stimulated the man at just the point where other condoms let him down.

PTI believes that the Twisted Pleasure infringes on its patents and claims that its successful entry into the condom marketplace has caused PTI severe economic pain. An estimated 6 to 9 billion condoms are used worldwide each year -- so getting an edge on the competition can mean serious profits.

This isn't PTI's first attempt to defend its patents. Five years ago, it failed in a similar effort to prevent another condom, the Inspiral, from being distributed in the United States. And here is where a kinky story starts to get a little bizarre. All three condoms -- the Pleasure Plus, the Inspiral and the Trojan Twisted Pleasure -- were designed by the same man, one Dr. Alla Venkata Krishna Reddy.

Dubbed by one condom retailer "the Leonardo of condom design," Reddy was the original owner of the patents now held by PTI. But Reddy's first condom company failed in the mid-'90s and he lost control of his patents in a bankruptcy auction. He did not, however, lose his zeal for the condom business. He returned to his native India and continued to tweak his innovative designs, and with the help of partners in the United States, soon reentered the American market, first with the Inspiral, and then with the Twisted Pleasure.

But his return to the America was greeted with great displeasure by Portfolio Technologies, the company formed to exploit the patents that Reddy had given up. PTI regards Reddy's new condoms as far too similar to his old ones. So, tragically, Reddy is being sued for violating his own patents.

The story of how Reddy lost control of his creation but returned to his native India to continue his quest for the perfect condom, only to find himself enmeshed in half a decade of litigative vituperation centered on prophylactic design, is a tale with more twists than any condom on the market. But there's more at stake in this legal battle than simply shelf placement at Walgreens. Reddy's great contribution to the universe of condom design, say his admirers, was to change the traditional perception of prophylactics. Instead of seeing them solely as barriers designed to block sperm from getting to the promised land, or to prevent the transmission of sexually transmitted diseases, Reddy viewed them as devices that could help enhance male pleasure.

What a concept! If condom use could make the act of sex more pleasurable, rather than less, then not only would a condom inventor stand to make a buck -- but the world would be a better, safer, healthier place.

From U.S. patent No. 5,082,004, filed May 22, 1990:

"It is an object of the present invention to provide a male condom which will be more acceptable to the male user by providing enhanced sensation during coitus and enhanced tactile stimulation during foreplay ... In the past, such devices have been tight fitting to prevent accidental dislodgment during coitus, [and] tight-fitting condoms bind the glans penis, resulting in restricted sensitivity and loss of stimulation during coitus."

Or to put it more bluntly: Condoms, historically speaking, suck.

This is an opinion that men have likely always shared, whether binding themselves with linen sheaves, sheep gut or the latest in latex. Condom use is generally motivated not by desire, but by fear. When technological developments, like the advent of the contraceptive pill, offer (for the male) a less intrusive approach, condom use, according to trackers of the industry, drops. But when external threats, like the rise of HIV/AIDS, emerge, condom use rises.

Reddy couldn't be reached for this story, but according to published reports and interviews with condom industry executives who know him, his primary motivation for condom innovation was health related. A graduate of Stanley Medical College in Chennai, India, he was researching AIDS at the Carbon County Memorial Hospital in Rawlins, Wyo., in the late '80s when he decided that the only sure defense against sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) was condom use. He apparently realized right away that the key to getting men to buy into condoms was to make more them more fun.

And so was born the first pouch-on-pouch condom: the Pleasure Plus.

According to the official patent, "the condom includes a pouch or pouches on the tubular pouch in the thin membrane material of the condom that will move back and forth on the underside region of the glans penis or in areas adjacent to and encircling the glans penis during coitus to provide enhanced stimulation and sensitivity to the male user of the condom."

The glans penis is the sensitive part at the end of the cock. Your typical condom features a constrictive layer of latex that grasps the head of the penis in a clammy death-grip, numbing all sensation. The Pleasure Plus adds a new locus of friction, a second pouch attached to the inside of a loose outer pouch so that there is, in effect, a moving part inside the condom, rubbing directly back and forth on the penis.

According to testimonials, the technique works. Outside of the relatively small community of condom inventors, marketers and manufacturers who have devoted their lives to prophylactics, the name Dr. A.V.K. Reddy is not a household word. But to those who took their contraception seriously in the mid-1990s, the Pleasure Plus condom was a revelation.

Sex expert Susie Bright, the host of "In Bed With Susie Bright" on Audible.com, and a longtime commentator on all things sexual, had never heard of Reddy. But she squeals with delight when told that he had invented the Pleasure Plus.

"I used to hoard them the way Elaine hoarded the Today sponge on 'Seinfeld,'" she recalls. "It was the only condom that offered any physical difference whatsoever. I've always said, forget the ribs and colors and all that bullshit. If the point is sensitivity and feeling good, the Pleasure Plus is the only alternative."

Adam Glickman, whose retail store Condomania was the first to sell the Pleasure Plus, recalls Reddy as "a man deeply concerned about condom effectiveness." At the time, Glickman says, "what was so refreshing and different about him was that he wasn't defining effectiveness in terms of safety and reliability, he was defining it in terms of acceptability and pleasure. No one had really defined condom performance so totally under those terms before him."

But despite the great reviews, the Pleasure Plus was hard to find. In fact, almost as soon as it became popular, it disappeared.

"It was a big mystery," Bright says. "We heard all kinds of rumors. It was there and then it was gone."

"Dr. Reddy is a little bit crazy professor, and a little bit passionate entrepreneur," Glickman says. "But while his strong suit is his ability to create these unparalleled condoms, his acumen as a businessman was unfortunately not quite as superior."

Tracing the trail through a succession of legal filings, what appears to have happened is this: Almost immediately, Reddy Laboratories International Ltd., the Bermuda corporation Reddy had created to manufacture and distribute the Pleasure Plus, ran into severe financial problems. Throughout the mid-'90s, Reddy struggled to keep the company alive but was eventually forced to sell off all its assets -- which were, chiefly, the two patents he had registered -- to creditors.

The largest creditor was the company's own president, John E. Rogers, and by 1998 he ended up owning the patents. Rogers, who formed PTI for the sole purpose of exploiting the patents, contracted with another firm, Global Protection Corp., to make and sell the Pleasure Plus. (Incidentally, the CEO of GPC, Davin Wedel, was the college roommate and former business partner of Condomania's Glickman.) Neither Rogers nor Wedel returned Salon's calls.

But Reddy was not dissuaded, and he ended up demonstrating a little more business prowess than he has been given credit for, not to mention some timely globalization savvy. He returned to his native India, secured some $7 million in financing, and set up a condom factory that produced his latest invention, the Inspiral, a condom with a single twisted protuberance slithering its way around the main chamber. His new company, Reddy Medtech, contracted with a Michigan businessman, Brian Osterberg, to distribute the Inspiral in the United States through Osterberg's company, Intellx. (On advice of counsel, Osterberg declined to comment on active litigation.)

John Rogers, Reddy's former creditor, was not amused. Although visually, the spiral pouch on the Inspiral was not identical to the P-shaped pouch on the Pleasure Plus, Rogers viewed the fundamental "pouch on pouch" innovation as identical. In March 1999 Rogers' company, PTI, sued Reddy in the U.S. District Court for New Jersey, seeking a preliminary injunction preventing the importation and sale of the Inspiral.

The injunction was denied. In one of the more entertaining opinions in a patent-infringement suit you are likely to run across, the District Court judge, Joseph Greenaway, ruled that PTI would be unlikely to prove infringement in a full trial and determined that there was no reason to grant an injunction. Greenaway's decision was later upheld by an appeals court.

But the story doesn't end there. Four years later, PTI renewed its legal quest, this time filing suit in Illinois against Church & Dwight, the consumer products conglomerate that sells Trojan condoms, which had by then concluded a deal with Reddy to sell a third condom, the Twisted Pleasure -- a condom that has two spirals winding around the main chamber. PTI also filed suit against Intellx in Michigan in March 2005, and in August 2005 the company lodged a complaint against all the parties involved before the International Trade Commission, a federal agency with jurisdiction over anything imported into the United States. (Excluding the ITC complaint, the other cases have all been stayed, pending the outcome of a new case in New Jersey, with the same Joseph Greenaway presiding.)

Why this flurry of new activity after several years of silence? There are a couple of possible reasons: the patents at issue expire in 2010, so there is a limited amount of time left to profit from them. Perhaps more important, the entry of Church & Dwight and Trojan into what PTI considered its specialized market niche posed a much larger threat than the initial appearance of Intellx and the Inspiral. Trojan is the largest-selling brand of condoms in the United States. As a result of the Twisted Pleasure's entry into the market, reads part of the ITC complaint, PTI and GPC have been "unable to price the Pleasure Plus product at a premium, the Pleasure Plus product being relegated to lower level shelves and/or pegs, loss of market share and loss of major customer Walgreens."

"This is speculation," says Glickman, "but I'm sure that John Rogers and Davin Wedel never agreed with the earlier court. At that time it was just Inspiral and Pleasure Plus, but once Church & Dwight got involved, it was a different story. The Twisted Pleasure has been enormously successful -- it's a top seller for Condomania -- and perhaps it was that success that prompted the folks behind Pleasure Plus to revisit the issue."

In the past three years, Glickman explains, growth in condom sales worldwide has been flat. "And that's a little distressing, given HIV, STDs and all of that is still out there and on the rise. But what has been growing is the specialty condom sector, these condoms that feature bells and whistles that are distinctly different from your standard condom. That market is growing 18 percent to 20 percent a year."

Glickman himself has a partnership with condom innovator, Frank Sadlo, to produce TheyFit condoms, which come in 55 sizes -- soon to be expanded to 90! -- and which he says have been hugely popular. He notes that there are condoms that now come preloaded with a dab of benzocaine -- designed, paradoxically, to numb the penis, as a boon to those suffering from problems with premature ejaculation.

Glickman's data about the state of the condom industry proved difficult to confirm. One condom consultant, John Gerofi, who runs a condom-testing company in Australia, was skeptical of the numbers. Even if the percentage figures were correct, notes Gerofi, the total market for specialty condoms was likely quite small compared to the overall market.

Still, the very existence of the multiple lawsuits, along with the ITC complaint (which itself can be a very expensive undertaking), indicates that there is serious money at stake. So before evaluating what is most likely the most morally significant aspect of the case, that is, the question of how best to fight STDs, it might be worth delving into the arcane world of patent litigation to figure out who, if anyone, actually has the law on their side.

There is little question that the three condoms in question have some clear visual similarities. To wit: All of them get kind of bumpy near the end part. But at the moment, the litigators in New Jersey are sparring over the hotly contested question of whether the Twisted Pleasure has a "generally constant diameter."

Condom measurement, it should be noted, is more complex than one might imagine. As one condom industry veteran serving as an expert witness for the defense noted, condoms are difficult to measure in their limp state. In the case of the Twisted Pleasure, even if one adheres to the relevant international condom standards, which require that a condom be "laid flat over the edge of a ruler, perpendicular to the condom's axis, allowing it to hang freely," a vexing problem still remains: How do you deal with the twisted part?

In point of fact, declared the expert, the bulging double helix that spirals around the latter portion of the Twisted Pleasure creates a constantly varying diameter.

Predictably, the lawyers for the plaintiff disagreed, furnishing the court with their own declarations from two more expert witnesses, an engineering professor conversant with all things latex and a Florida doctor with "expertise regarding male and female genitalia and the interaction thereof." These experts argued that the Twisted Pleasure has "valleys" between the spirals which remain in permanent contact with the penis, thus giving the condom a constant diameter.

Why does condom size matter? Because in a patent-infringement suit, perhaps more so than with most litigation, little details count. Lawyers for Church and Dwight (the Trojan company) are asking that the case be summarily dismissed, based on their contention that one of the patent claims at issue, which describes the condom as having a "generally constant diameter," does not apply to the twisty, unevenly bumped Twisted Pleasure. Should the judge agree with C&D, that fact alone might be enough to get the lawsuit thrown out.

Similarly, in 1999, PTI's attempt to get an injunction preventing distribution of the Inspiral was denied by Judge Greenaway after his own investigation (not his personal experience, mind you) of the two condoms determined that they were sufficiently dissimilar that PTI had little likelihood of winning a full trial. His reasoning followed lines that are reminiscent, in their exquisite attention to detail, to the reasoning employed by C&D's lawyers.

Greenaway noted, for example, that in his opinion the language in the patent appeared "to limit the protected stimulation to the area of the glans penis." The spiral-shaped pouch on the Inspiral went beyond just that region, he observed, and extended further down the shaft of the penis. He also pointed out that the patent described the condom's second pouch as "having its inner surface spaced radially outwardly" from the tubular portion of the condom, thus providing "looseness" between the tubular portion and the outer surface of the glans penis. But, concluded the judge, "the second pouch of the Inspiral condom is not spaced radially outwardly from the condom. Instead, the second pouch of the Inspiral condom is spaced spirally extending from the closed end of the condom longitudinally down the shaft."

The spiral shape of the second pouch, decided the judge, "actually results in no looseness."

Now, even a cursory examination would appear to the layman to indicate that if anything, Trojan's Twisted Pleasure is even more unlike the Pleasure Plus than the Inspiral. And given that the same judge is presiding over the case, an outsider might be excused for thinking that PTI's prospects of winning, the second time around, are rather bleak.

Not necessarily, says Paul J. Kozacky, a lawyer working on the case for PTI. First of all, wrote Kozacky in an e-mail, even though an appellate court upheld Greenaway's denial of the preliminary injunction, it did not fully agree with his decision. In fact, the three-paragraph affirmation of the decision states that "this court does not endorse the district court's claim interpretation." The judge writing the opinion took particular pains to dispute Greenaway's contention about the limits on the area of protected stimulation expressed in the patent.

As far as Kozacky is concerned "their opinion is a strong indication that the Inspiral product does indeed infringe on PTI's patent."

Lawyers for C&D did not respond to inquiries, and C&D's director of marketing did not return a phone message. And so the litigation continues, while the condom world waits.

But let's step back a second. If Reddy's primary motivation was to fight disease -- and if, as is manifestly true, health professionals consider condoms to be an essential weapon in the war on AIDS, then why are we wasting time wrestling over obscure patents? Shouldn't the goal just be to forge ahead and get condoms with the latest bells and whistles into the hands of everyone who needs them? Isn't there a point where the public good transcends the profit motive? Let a hundred Pleasure Plus condom imitators bloom! Alas, despite the noble dream that enhancing male pleasure will help save the world from the scourge of STDs, there are some cold, hard reasons why Reddy's pouch-on-pouch breakthrough (admittedly, a bad word to use when discussing condoms) may not be the answer to global sexual disasters.

For one thing, as outlined in "The Male Latex Condom: Specification and Guidelines for Condom Procurement," published by the World Health Organization, condoms with unusual shapes are specifically not recommended for distribution by reproductive health and family planning programs.

"Anecdotal information from testing laboratories suggests that they are more likely than smooth condoms to fail critical test requirements and have therefore not been recommended in this specification."

In other words, they are supposedly more likely to break, an assertion vigorously denied by Condomania's Glickman, who says he has seen no studies proving such a claim.

But perhaps more important, "specialty" condoms, also called "novelty" condoms, are more expensive. And in a world where family-planning agencies are calling for donors to provide them with billions and billions of condoms, price counts.

But perhaps most telling was a study, recently concluded in Jamaica, that tracked condom usage among men who were given a choice of four condoms, including the Inspiral. Dr. Markus Steiner, the researcher in charge of the study, determined that not only did the men quickly abandon the novelty condoms and return to their regular old familiar condoms, but those men who did use the novelty condoms demonstrated a slightly higher incidence of sexually transmitted infection.

"In fact, we had a hard time giving away the Inspiral condoms after the study," notes Steiner, who concluded that "providing 'Cadillac condoms' does not appear to be justified if resources are scarce."

"I think the participants in Jamaica just did not like the feel of the loose-fitting condoms," Steiner says. "We conducted a very similar set of studies in Ghana, Kenya and South Africa."

Does that mean that the dream is dead?

"Never say never!" Steiner says. "We are disappointed by the current findings. But for the time being, we think money is definitely best spent on ensuring access to condoms and appropriate counseling. But we remain optimistic that design improvements in the future could lead to increased condom use."

If that indeed proves true, then somewhere down the line, future researchers and family-planning specialists may want to give a shout-out to Dr. A.V.K. Reddy. No matter how the patent case in New Jersey plays out, his contribution can't be ignored. "Dr. Reddy," says Glickman, "was just way ahead of the curve in recognizing that the condom could be so much more than just a medical device to provide protection."

Shares