My daughter went to the war and all I got was this lousy memoir.

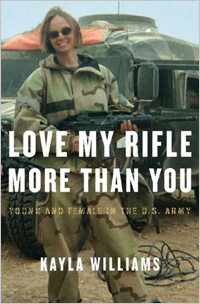

The men get “Jarhead,” a hauntingly beautiful and disturbing recounting of the Gulf War by former Marine Anthony Swofford, a man incapable of writing an uninteresting sentence. Chicks get “Love My Rifle More Than You” by 28-year-old Kayla Williams, a woman incapable of writing a complete sentence, though she had a ghostwriter, Michael E. Staub. The book follows Williams — who joined the Army Reserve in 2000 to train as an interpreter — the whole way to Iraq, where she was deployed as an Arabic linguist. There are tidbits of good writing and sound insight strewn like gold nuggets here and there, but it’s up to the reader to gut it out, like a five-mile hike in full battle gear, to find them.

I couldn’t get my hands on a copy of this book fast enough. Like Williams, I am a former military linguist — though I was never able to finagle my way into a war zone. Finally, a look into the world of war zone women with all the sexual and political drama that portends; a pas de deux with Swofford’s “Jarhead,” Uris’ “Battle Cry” and O’Brien’s “The Things They Carried.” If only it had been a smart memoir. Instead, we get a self-absorbed lost girl playing GI Jane dress-up. Focused on her year in Iraq from February 2003-04, “Love My Rifle” is a meditation on what it means to be in that 15 percent of the Army that is female and at war — its contradictions, its perks, its punishments, its absurdities and its epiphanies. Or, at least, it was meant to be, before Williams’ need for attention and approval smothered her insight. Still, in spite of herself, Williams provides a peephole, if not a window, onto the world of the woman warrior.

I want to feel for Williams, truly I do. The military is full of diamond-in-the-rough kids like her who might have made a few mistakes but still know that there are uncharted worlds inside them. They know they were destined for a polyester uniform; making a break for the GI’s outfit, rather than the burger flipper’s — or, God forbid, the inmate’s — is a daring demand to be taken seriously, to be invested in, to be challenged. To be seen. For poor or lost kids, joining up is an escape attempt, a prison break. Our all-volunteer military remains tenable only because these strivers somehow know that hot marches in the sun and nights spent sleeping in a foxhole will open the door to whatever’s buried inside their dreams.

But for the can-do pragmatism of the draftless military, the world would have happily consigned these nondescript kids to Folsom — or Molson’s. The military’s is a complicated psyche; for young people like Williams, there is relief and gratitude at finding a home, but there’s also anger — See what a drastic step I had to take to get a break! (Perhaps that explains the average GI’s “fuck you” conservatism. I made something from nothing, they think; screw you if you choose not to.) On the one hand, the lost kids just want to be left alone to do the fulfilling and secure jobs they’d bootstrapped themselves into. On the other, they want someone to notice how smart, how dedicated, how innovative under fire they are, even though Mom didn’t go to Choate and Pvt. Laquita Jones was never getting to Europe except by C-130. People join up to find out what they’re made of, and one of the precious few compelling arcs in Williams’ memoir is her rumination on her risk taking. Then there’s the other 98 percent of the book.

Williams may have been a good soldier, but she should reconsider her plan to become a journalist. Hell, she’s not even a good buddy, the bedrock of GI mutual respect. Hey, all you infantry grunts who kept Williams’ linguist ass alive, here’s what she thinks of you:

“[They] would always tell me: ‘You’re really smart. You’re smarter than we are.’

And I’d give them credit, too. I would tell them: ‘Sure, I’ve read more books than you guys. I can speak Arabic. But I couldn’t fix my truck if my life depends on it. I know nothing about engines. I would never be able to understand your equipment. You are all smarter than I am about how to make things work.’

Being around these guys and military personnel in general had given me a whole new appreciation for non-intellectual skills. These were people with manual skills. They knew how to use their hands. They were not afraid to get sweaty or dirty. And I respected them for that.” (Emphasis added.)

First of all, there isn’t a grunt in the world dumb enough not to have heard that for the insult it was and to have suggested that Williams kiss his “non-intellectual” ass as he went off to inform his buds what a loser their 98 Golf (linguist) is. (Swofford, the far superior GI writer here, was a grunt, by the way.) During my six years enlisted in the Air Force, I don’t recall having had many GIs kiss my ass for being the smart, well-read linguist that I was — unless they were trying to get me naked. Most likely, they were thinking A) you got no idea what I do with my free time, and B) you might be able to order beer in Korean, but I keep Eagles (F-15s) flying!

GIs have sturdy, well-fortified egos, both because their bosses regularly, quite consciously, pat them on the back and because their jobs are extremely specialized, especially their pecking orders. Most often, it was officers, who are sort of like parents to the junior enlisted, who sang the praises of GIs. Having learned the significance of this praise while I was enlisted, I made sure to dole out plenty of it during my six years commissioned. It was my duty, but more than that, I had the good fortune to supervise people too well-raised and too well-adjusted to fish this shamelessly for approval. All of that is to say, this memoir isn’t really about being young and female in the Army. It’s about being young and insecure in the world. It’s about being an immature, needy woman who learned all the wrong lessons while at war.

Indeed, “Love My Rifle” contains enough score settling, petty rants against officers and rank insubordination that I wish Williams could be retroactively subjected to a good old-fashioned GI “blanket party” and then thrown in the brig. She is the garden-variety “barracks rat” malcontent who seethes when the new ranking NCO (non-commissioned officer) has the gall to inspect her new domain and whom Williams childishly dismisses as “technically in charge.” No, she was actually in charge. Good Lord, how I loathed those women who wanted to have the only pair around, wafting prettily on a cloud of estrogen while easily led men did all their work for them.

The challenge for any memoirist is to tell the readers how wonderful and interesting she, this person they’ve never heard of, is; the trick — and this is key — is to do it without making them roll their eyes and hate you. But just when you think she might trip up and captivate, Williams gets in her own way: “Leaving town has tended to be my way of ending relationships…” — Stop, Kayla! Stop right there. But no — “that I otherwise had no idea how to end.” Williams writes like drunks walk.

Page after page after page, Williams always goes a phrase or a sentence too far, capping off yet another cluster bomb of self-congratulation (“So I graduated from high school at 16 and went directly to college”), preening (“I started French lessons when I was really young, and mom [took me to France]. Awesome experiences”), mastery of the obvious (“Quinn was the only member of my team with whom I could actually be vulnerable … And now he was going. So I knew I would miss him”) and the kind of bad writing and neediness that just whittles your brain down to a blunt nub.

But even Williams can’t entirely ruin the story of a woman at war, hard as she tries. Here’s a nice bit: “You’re messing with me, I said, feeling messed with.” One of a few redeeming sections is about traveling in convoys in Iraq, given the relentless danger from roadside bombs and snipers. Even a linguist who claims to read a book a day has to man a weapon and make split-second decisions about whether or not to fire. She builds the suspense of the patrols and captures the surreality of a world at war. She writes:

“Just then a passenger on my side turns to look for the first time. It’s a little boy. Not more than eight or nine years old. I’m pointing my weapon at a boy who looks exactly like [a former Arab boyfriend’s] brother. The boy looks at me looking at him. I lower my rifle and hold it with one hand across my knees. Without thinking, I wave at the boy with my other hand. And after a moment, he waves back.”

Still, Williams quickly loses her focus, switching from recounting the woman’s experience of war to concentrating on her petty battles with her superiors, and frustrates the reader again and again as she tries to understand what Iraq was and is like for Western women. “Apparently,” she writes, “Iraqis asked our guys if we were prostitutes. Employed by the U.S. military to service the troops in the same way the Russian army managed sex for its soldiers in Kosovo. I didn’t want anyone to think we were the U.S. equivalent of that!”

While the banality of Williams’ insights is what arrested my attention here, once stopped, I began to wonder why the budding journalist already at work on a memoir didn’t interrogate this rather compelling notion. During my two years in Korea, we all heard about the many rich Korean men who offered blond GIs hundreds — no, thousands — of dollars for just one night of sex. But it was always the “friend of a friend” or a “friend who’d just rotated back to the world” that it had happened to. Why not track down one of these guys and find out exactly what the Iraqis said? Did any Iraqi men make lewd suggestions to Williams? Ogle her? Offer her money? She recounts many encounters with Iraqi locals, often when she was the only female GI around, with not one liberty taken, not one suggestion that they thought her a ho. It never occurs to Williams that this was much more about good, old-fashioned American misogyny than anything else. While it’s entirely likely that Iraqis assume most Western women are of “easy virtue” (they get MTV, after all), a complicated phenomenon like the Middle Easterner’s attitude toward Western women deserves much better treatment from someone with firsthand knowledge.

As good as Williams gets comes early on when she’s describing the “Queen for a Year” phenomenon; the farther men are from home, and the fewer women there are, plain Jane soldiers begin to morph into supermodels. Williams admits taking advantage of her gender to get out of yucky chores and being inconsistent in her reaction to the men’s constant scrutiny:

“A woman soldier has to toughen herself up. Not just for the enemy, for battle, or for death. I mean to toughen herself to spend months awash in a sea of nervy, hyped-up guys who, when they’re not thinking about getting killed, are thinking about getting laid. Their eyes on you all the time, your breasts, your ass — like there is nothing else to watch, no sun, no river, no desert, no mortars at night.

“Still, it’s more complicated than that. Because at the same time you soften yourself up. Their eyes, their hunger: yes, it’s shaming — but they also make you special. I don’t like to say it — it cuts you inside — but the attention, the admiration, the need: they make you powerful. If you’re a woman in the army, it doesn’t matter so much about your looks. What counts is that you are female.

“Wartime makes it worse. There’s the killing on the streets, the bombs at the checkpoints — and the combat in the tents. Some women sleep around; lots of sex with lots of guys, in sleeping bags, in trucks, in sand, in America, in Iraq. Some women hold themselves back; they avoid sex like it’s some weapon of mass destruction. I know about both.

“And I know about something else. How these same guys you want to piss on become your guys. Another girl enters your tent, and they look at her the way they looked at you, and what drove you crazy with anger suddenly drives you crazy with jealousy. They’re yours. Fuck, you left your husband to be with them, you walked out on him for them. These guys, they’re your husband, they’re your father, your brother, your lover — your life.”

We were robbed. When you see what Williams is capable of when she’s not in her own way it’s hard to forgive her for the book she ended up writing.

To be sure, the memoirist plays a dangerous game. Unless something spectacular happened to you (like being held hostage, say), it isn’t possible to pen such a book without being narcissistic and convinced of one’s own special wonderfulness. So, the problem isn’t that Williams is self-absorbed. It’s that her self-absorption penetrates no more than inch-deep into her own psyche and cringing need for attention and approval. The problem isn’t that she thinks she’s the shit; it’s that she provides no evidence of said shit-ness. I don’t even mind that she name-drops Chomsky, Zinn and the Dead Kennedys in one tiny paragraph to bludgeon us with how eclectic and well-read she is; I mind having to deal with a poser whose poses are so amateurish. Most of all, I mind that, given the dearth of women’s writing on this subject, I still have to demand that you read this book and fill in the gaps for yourself. Still, beware: This isn’t a memoir about being female in the Army. It’s about still being lost in the world.