Rock 'n' roll was not a language spoken in my parents' house. But that wasn't unusual in the '70s; the generation gap wasn't just a demographic term, it was a living, breathing beast. When I was 14, I won tickets to see my favorite band, the Rolling Stones, at the Boston Garden but, because of some Keith-related snafu (a fight and an arrest, if I remember correctly), the concert was going to be delayed until midnight. I called my parents from a pay phone at the Garden to tell them I'd be late, only to find my father in an uproar. He demanded that I forget about the Rolling Stones and come home that minute. I stayed. Although my parents were in their early 20s when they had me (10 years younger than I was when I gave birth to my son), there was no common cultural ground between us.

The Stones Incident came to symbolize everything that I feared about becoming a parent. Would the generation gap yawn as wide for me and my kid? Would I become a well-meaning but clueless authority figure? But I need not have worried. There are many things I could never have imagined about parenthood: that a dewy baby boy could grow into a slouchy, unkempt, 6-foot-tall 13-year-old in what seemed like the space of a breath, for instance, or that he would become a teenager in a country that's divided over a dubious war, just as it was when I was a teenager. But the thing that was most unimaginable to me on the night of that Stones concert has turned out to be the thing that has, so far, surprised me the most about being a parent: My son and I go to rock concerts together.

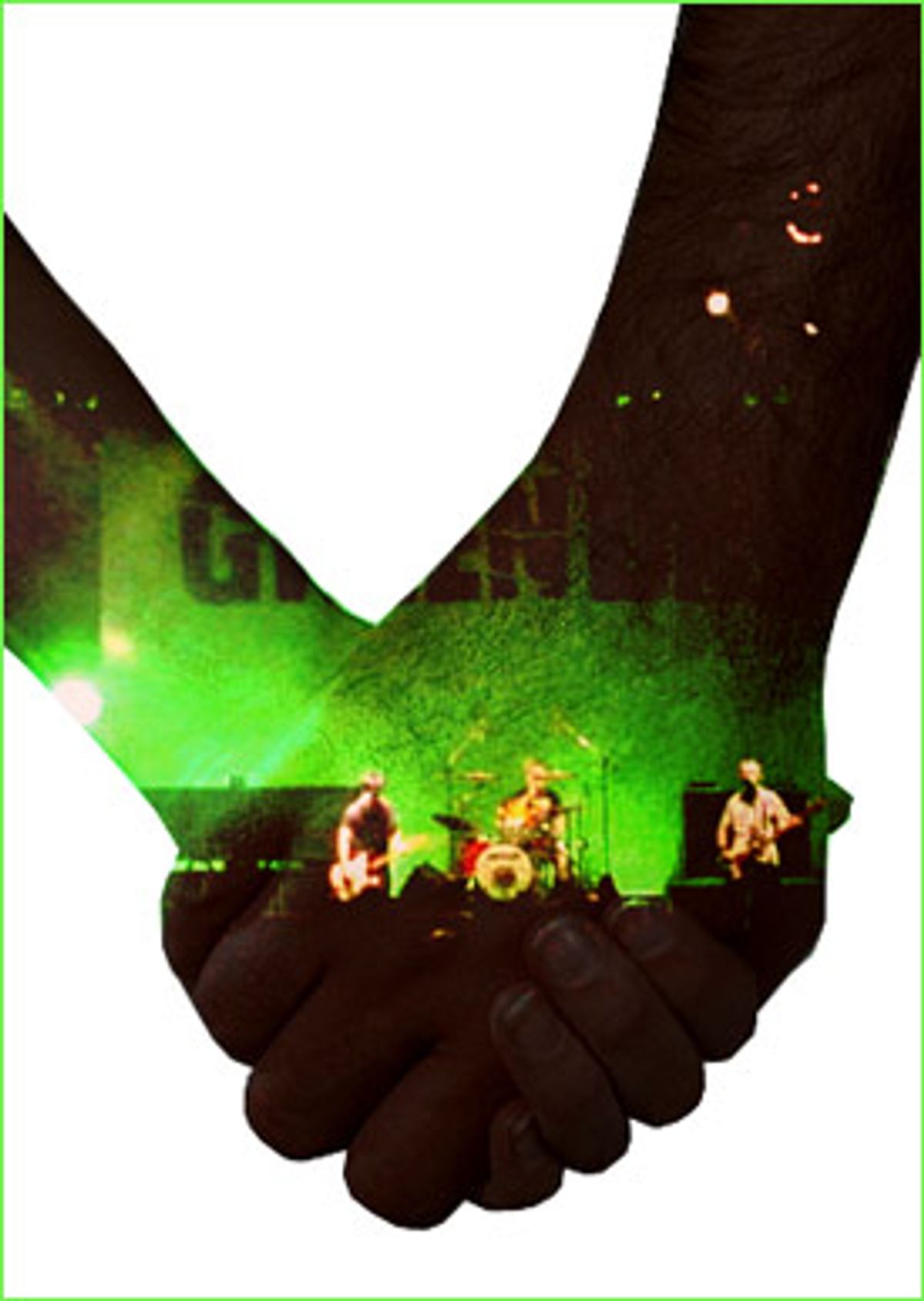

When I was 13, there was no freakin' way my parents would have taken me to a rock concert. Now here I was, 34 years later, with my husband and (slouchy, unkempt) 13-year-old on a clear, crisp September night, at what was, for my son, the equivalent of that Rolling Stones concert: Green Day at SBC Park in San Francisco. The East Bay trio was celebrating the biggest album of their career, the ferociously anti-Bush cannonade "American Idiot," and this show was their triumphal homecoming. When I first heard Green Day on the radio 11 years earlier, I nearly wept at how much they echoed the Clash, my defunct heroes, the greatest band, ever. The musical revolution that the Clash promised had only been delayed, blooming again in Billie Joe Armstrong's fractious singing and the band's exhilarating three-chord thrash.

When my son discovered my Green Day CDs, I quietly rejoiced. He had previously resisted my musical suggestions and was content listening to his lightweight Smash Mouth CDs and (ick) the Dave Matthews Band. But Green Day lighted a fuse and he was soon riffling through my collection to sample the Clash, the Sex Pistols and the Ramones, as well as the Who and the Kinks, all of them Green Day's spiritual fathers. Billie Joe, Tre Cool and Mike Dirnt are much cooler teachers than I am, and I thank them for it.

I also thank them for the unvarnished anger of the "American Idiot" album, which has become the soundtrack for my son and his friends' nascent liberalism. I wasn't sure how to talk about the war or about the erosion of civil liberties to my son without seeming like a ranting old lady. But "American Idiot" gave me an opening. Note to politicians: The 13- and 14-year-olds of today get their news from "The Daily Show" and their attitude from Green Day and the cool-again '70s punks. Their hair is long or color-streaked, they think the president is a bozo, they know we're in Iraq for the oil and they aspire to own Priuses, not Hummers. Fear them. They are the old antiwar movement redux.

"This song is not anti-American, it's anti-waaaaaaaaaaar!" screamed Billie Joe at SBC Park, kicking into "Holiday" ("I beg to dream and differ from the hollow lies/ This is the dawning of the rest of our lives"), and 45,000 fists pumped the air. I looked around at all the families like us, and felt a curious sense of time shrinking and falling away. I was as happy as I had been at that Stones show at 14, and at Clash shows at 22. Earlier that night, we had sat in the golden San Francisco dusk waiting for the show to begin. We watched the people wandering around the stadium: Parents and kids, lone adults wrangling four or five preteens, pierced, plaid-skirted girls and waifish, T-shirted boys taking pictures of each other with their camera phones. An Irish punk band called Flogging Molly ambled onstage while the sky was still light and blew us away. They dedicated a song to the Clash's Joe Strummer, my poor, dead idol, and my son and I clapped loudly. Two girls on the edges of left field danced a jig to the music and one suddenly turned a running cartwheel. The night was full of joy and release.

Between bands, we listened to the music mix on the P.A. system -- "God Save the Queen," "I Fought the Law," "Blitzkrieg Bop" -- and my son exclaimed, "They've been raiding my CD collection!" We were happy and close the way a family should be and I marveled at the weirdness of it all, that rock 'n' roll, the music of rebellion -- of my rebellion against my parents -- should be our bond. I could never have imagined this that night at the Stones concert, listening to my dad screaming at me through the phone. How fortunate I am to be able to speak the same language as my son, to know that his rebellion will be against something that really matters, a rebellion we can share.

Over the sound system, Cheap Trick were singing "Mommy's alright, Daddy's alright, they just seem a little weird," and I thought, OK, this is all OK.

Shares