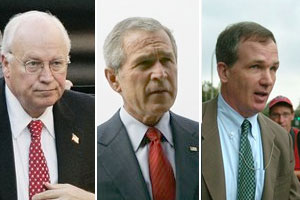

Tensions between Vice President Dick Cheney’s office and the CIA were nearing a peak in the summer of 2003, months after the initial invasion of Iraq. I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby, Vice President Dick Cheney’s chief of staff, fumed at what he saw as a “hedging strategy” by the CIA to deflect blame for bad Iraq intelligence.

“I recall that Mr. Libby was angry about reports suggesting that senior administration officials, including Mr. Cheney, had embraced skimpy intelligence,” wrote New York Times reporter Judith Miller, in a recent summary of her meetings from 2003. “Such reports, he said, according to my notes, were ‘highly distorted.'”

This is the context in which the White House lashed out against Ambassador Joseph C. Wilson, who had accused the administration of twisting intelligence to make a case for war, and Valerie Plame, his wife. The couple were living, breathing examples of the threat unchecked naysayers posed to the reputation of the Bush administration. So in the summer of 2003, White House officials leaked Plame’s identity to the press in an effort to discredit her husband. Two years later, special prosecutor Patrick Fitzgerald is faced with the task of examining this same landscape as he decides whether to file charges for the leak of Plame’s name.

The stakes in Fitzgerald’s investigation rose dramatically with the report in Tuesday’s New York Times that Libby first learned about Plame from a conversation with Cheney — not from journalists, as Libby reportedly told the grand jury. Whatever the legal implications of Cheney’s alleged involvement, it puts the vice president himself squarely in the middle of the effort to discredit Wilson.

If Fitzgerald hands down indictments, Washington will face a political upheaval not seen since the Clinton impeachment. But that will not be the only, or even necessarily the most important, effect of Fitzgerald’s decisions. The resulting criminal process could also, for the first time, throw open the doors on the inner workings of the White House during one of the most controversial periods of recent American history. After 22 months of investigation, Fitzgerald, a Chicago-based prosecutor, may know more about the internecine battles that led to the outing of Valerie Plame than even the most well-connected intelligence wonks.

The question now is not only whether he’ll indict anyone, but whom he’ll indict, on what charges, and how much the prosecution will wind up revealing about who was responsible for the faulty intelligence that led the nation to war.

To date, investigations of the missteps have been piecemeal and held back by Republican recalcitrance. The Senate Intelligence Committee issued a report in July 2004 that looked at many of the mistakes of the intelligence community. A second report, on the possible misuse of intelligence by the White House, the role of the Pentagon in freelancing intelligence operations and other issues has been delayed more than a year amid partisan bickering in the Senate.

Interviews with government officials and outside observers reveal a wide range of outstanding questions that official inquiries have not yet resolved. Some of these questions may never be answered with certainty. But others, some now hope, could be answered in the coming days or months by Fitzgerald.

Here are four of the biggest questions Fitzgerald’s investigation may be able to answer:

Several journalistic reports have asserted that Cheney’s office did pressure the intelligence community to come up with the “right” kind of information. In a 2003 piece in the New Yorker, veteran journalist Seymour Hersh reported that “[s]enior C.I.A. analysts dealing with Iraq were constantly being urged by the Vice-President’s office to provide worst-case assessments on Iraqi weapons issues. ‘They got pounded on, day after day,’ one senior Bush Administration official told me, and received no consistent backup from [former CIA director George] Tenet and his senior staff. ‘Pretty soon you say “Fuck it.” ‘ And they began to provide the intelligence that was wanted.”

Despite such reports, and a 521-page report by the Senate Intelligence Committee, this officially remains an open question. In 2004, the committee concluded there was no evidence that “Administration officials attempted to coerce, influence or pressure analysts to change their judgments” about Iraq’s weapons programs. For Senate Republicans and White House allies, this was the last word on the subject.

But for many other observers, including some of the committee’s Democrats, it was just the beginning of the discussion. “We had major disagreements on pressure,” the ranking Democrat, Sen. Jay Rockefeller, D-W.V., said after the report was released. “The definition of pressure was very narrowly defined by the report.”

Committee staff appeared to base their conclusions on the fact that no one in the intelligence community had come forward to claim a specific incident of coercion. Some, however, did make complaints about pressure to Richard Kerr, a former deputy CIA director who completed his own review of prewar intelligence. In a report produced in July 2003, Kerr said repetitive requests for reporting and analysis from policymakers created “significant pressure on the Intelligence Community to find evidence that supported a connection” between Iraq and al-Qaida. “They were being asked again and again to restate their judgments,” Kerr told Vanity Fair in 2004.

In a separate report, the CIA ombudsman told the committee that there was significant “hammering” by the Bush administration on Iraq intelligence, and several complaints by analysts that they were under pressure.

In a third report, made public this summer, Kerr elaborated on the problem. In recent years, he wrote, the intelligence community shifted “away from long-term, in-depth analysis in favor of more short-term products intended to provide direct support to policy.” This led to “quick and assured” responses by intelligence analysts to policymakers, answers that “gave the appearance of both knowledge and confidence that, in retrospect, was too high.”

Libby is reported to have been deeply involved in analyzing and distributing intelligence on Iraqi issues. The vice president, himself, visited CIA headquarters at least five times during the run-up to war, to question analysts. Yet little is known about the vice president and Libby’s dealings with analysts, or what, if anything, the White House did that was inappropriate. A criminal trial of Libby, or others in the vice president’s office, might peel back this curtain.

Observers have long noted that the 2002 NIE, even with all of its qualifications and footnotes, was far more confident about the presence of Iraqi WMD than previous intelligence estimates had been. “The truth is that the U.S. unclassified assessments offered fairly reasonable judgments until 2002,” Joseph Cirincione, the director of nonproliferation at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, wrote in a 2004 article. “A marked shift, however, occurred with the October 2002 NIE. The findings became far more dramatic, specific and certain.”

At roughly the same time, the intelligence community released a white paper to the public that eliminated many of the caveats about the Iraqi WMD intelligence. The paper even included a sentence that suggested Iraq had the potential to target the “US Homeland” with biological weapons. According to Democratic senators, this assertion has no basis in the classified version of the document.

It is still unknown what role, if any, Cheney and his staff played in these anomalies. But the Fitzgerald investigation has already offered a window into the inner workings of how Libby dealt with these issues. In her testimony before the grand jury, Miller said that Libby told her that the classified version of the 2002 NIE had firmly concluded that Iraq was seeking uranium.

He was, at minimum, overstating the case. As Newsweek has reported, the classified estimate “showed almost precisely the opposite.”

The so-called Niger documents, which were given to an Italian journalist in 2002, were later discredited by the United Nations as crude fabrications. Speculation has swirled ever since about who created and distributed the documents. In March 2003, at the request of Sen. Rockefeller, the FBI opened an inquiry into the matter. Since then, both Sen. Rockefeller and Sen. Roberts have been briefed on the progress of the investigation, according to a Senate aide.

This summer, Sen. Rockefeller asked Sen. Roberts for permission to have the FBI brief the entire Intelligence Committee on the matter. No briefing has been scheduled, and it is not clear if the FBI findings will ever be made public.

But a recent report by UPI, quoting sources at NATO, revealed that Fitzgerald’s team “sought and obtained documentation on the forgeries from the Italian government.” This included a full, as yet unpublished, report to the Italian Parliament on the documents. It is possible that Fitzgerald now knows more about the origins of the forged Niger documents than many members of the Senate Intelligence Committee.

(In a series of articles that ran this week, the leading Italian newspaper La Repubblica claimed that the Italian military intelligence service, or SISMI, was behind the forgeries, and that the head of SISMI bypassed the CIA and took the documents directly to Stephen Hadley, at the time the deputy national security advisor. According to the articles, Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi wanted to curry favor with the Bush administration. Laura Rozen gives an account of the articles in the American Prospect.)

Here, the question is not whether Cheney and high-ranking Pentagon civilians circumvented the normal intelligence vetting process, but to what extent. It is known that both Cheney and other top administration officials, including Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Doug Feith and former Undersecretary of State for Arms Control John Bolton, were contemptuous of the traditional intelligence process. Feith was in charge of a secret shop, the Office of Special Plans or OSP, whose main purpose was to cherry-pick intelligence that could be used to support the war. Administration officials also made widespread use of bogus intelligence from Iraqi exiles without going through ordinary channels. Back in 2002, a lobbyist for the Iraqi National Congress (INC), a discredited group of Iraqi expatriates with close ties to the White House, wrote a memo describing his contacts in the U.S. government. Among those listed, according to a report in Newsweek, were John Hannah, an aide to Vice President Cheney, and William Luti, who would work as an aide to Feith in the OSP.

Such high-level contacts with what was essentially a foreign — if denationalized — group of intelligence agents has raised eyebrows in Congress. Under the National Security Act of 1947, federal officials engaged in intelligence activity must inform the Senate Intelligence Committee. “If they were undertaking intelligence activities and they were not notifying this committee, they would be in violation of the law,” says an aide to Sen. Rockefeller.

Fitzgerald, who has interviewed Hannah as part of his investigation, may be able to shed light on this episode.

Since the invasion, other reports have suggested that officials close to Vice President Cheney embarked on additional intelligence-gathering missions overseas, including a secret meeting in Rome with Manucher Ghorbanifar, an Iranian arms dealer. According to Democratic senators, Feith’s shop also directly briefed the White House in September 2002 on an alternative analysis of Iraqi intelligence, one that has since been shown to be even less credible than the CIA estimates. The now-departed Feith, meanwhile, has been pummeled in the press by his former colleagues. Most recently, former State Department Chief of Staff Col. Lawrence Wilkerson told a think tank audience, “Seldom in my life have I met a dumber man.” (Wilkerson was actually complimentary compared to Gen. Thomas Franks, who according to Bob Woodward called Feith “the fucking stupidest guy on the face of the earth.”)

Last year, the Pentagon stopped cooperating with the Senate Intelligence Committee. Sen. Roberts has, so far, refused to force cooperation, all but sinking the hopes of Americans who want the government to get to the bottom of its own missteps.

But then there is Fitzgerald. It will be a remarkable irony if an investigation into a relatively minor misdeed ends up doing what Congress could not: shedding light on the hidden machinations of an administration bent on war.