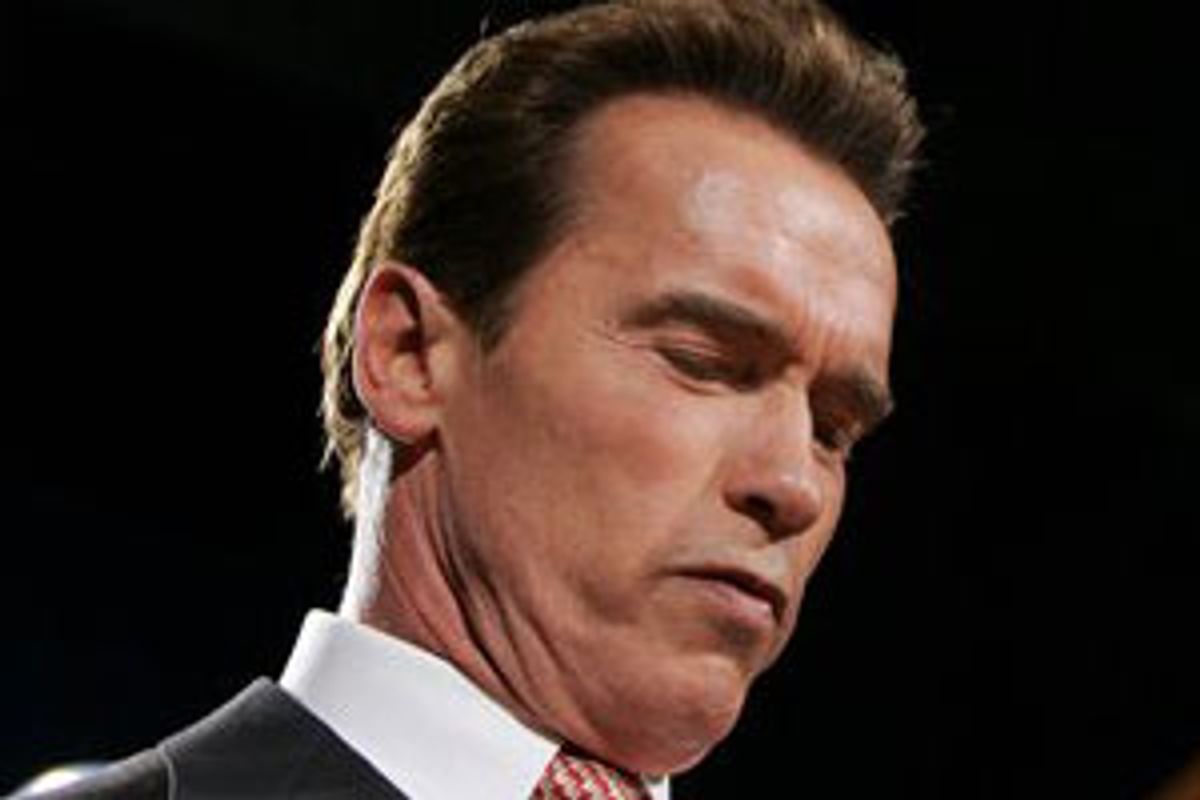

Aug. 31, 2004, was the greatest day in Arnold Schwarzenegger's political life. He walked to center stage at Madison Square Garden and stood before thousands of adoring fans, all the power brokers of the Republican Party, and delivered the keynote address of the convention's second day. Millions of people watched him stake his claim to the future of American conservatism. "To think that a once scrawny boy from Austria could grow up to become governor of the state of California," he said, "and ... stand here in Madison Square Garden and speak on behalf of the president of the United States. That is an immigrant's dream! It's the American dream."

For a small but crucial species of conservative intellectual, Schwarzenegger was a gift from God. They had seen the Republican Party, under George W. Bush's leadership, sell its soul to Bible Belt conservatives, mouth religious pieties, and threaten to stack homosexuals and evolutionary biologists onto a pyre and light a match. Urbane libertarians like Andrew Sullivan and the Manhattan Institute's Brian Anderson desperately needed a charismatic leader to save them from the knuckle-draggers. Someone hip and cosmopolitan, who would celebrate the free market's virtues and embrace the aspirations of millions of immigrants. Only a "South Park conservative" -- named after the irreverent and often anti-liberal animated TV series -- would ever win back the right wing. A year ago, Schwarzenegger looked like just the man for the job.

Look at the mess their hero's made now. Schwarzenegger staked every cent of his political capital on four ballot initiatives to fix some of California's worst problems. On Tuesday, voters rejected every single one. Now the best chance for reform in California has been squandered, and such an opportunity is hardly likely to return anytime soon.

For years California has faced a recurring budget crisis, the entrenched public employee unions wield enormous power, and the legislative landscape is marked by districts deliberately drawn to guarantee no election will ever be contested. Schwarzenegger asked voters to take redistricting power out of the hands of politicians, effectively ban unions from contributing to political campaigns, institutionalize a spending cap, and make it harder for schoolteachers to secure tenure.

But the substance of the measures appeared almost irrelevant on Tuesday. Voters seemed to reject them merely to repudiate the governor. According to a recent Field Poll, only 36 percent of Californians would elect Schwarzenegger to a second term. After Bush, the Terminator is the least liked man in public life right now.

The governor's flameout illustrates the limitations of the South Park conservative temperament. South Park conservatism is a reaction to stultifying p.c. moralizing, and its adherents get a kick out of tweaking hypocrisy and exploding taboos. They're socially liberal and fiscally conservative; they like their government small, their markets free, and their drinks straight up. They don't care about fags, but they get annoyed when someone says you can't say "fag." And their icons are maverick, iconoclastic political leaders who aren't afraid to call 'em like they see 'em. Think Rudy Giuliani. Or Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Giuliani made such a profound impact on New York City precisely because he refused to accept the conventional wisdom that the city was sprawling and essentially ungovernable. He didn't care if he offended the sensibilities of the entrenched power bases -- he just plowed ahead and damned the torpedoes. But he had eight years to do his job. Schwarzenegger took this brand of iconoclasm to its logical extreme, played the populist card for all it was worth, tried to push through massive reforms in 10 months -- and failed spectacularly.

In short, Schwarzenegger forgot that politics matter. He thought he could remake California on swagger and charm, endlessly promising to bypass corrupt politicians and take his case directly to "the people." But politicians exist for a reason; government is complicated, and most people would rather someone else did it.

In January, Schwarzenegger called a special legislative session to enact his reform package, gave the Legislature about two months to work it all out, and then called a special election when, for some strange reason, his colleagues didn't finish the job of reorganizing California's government according to his timetable. He thought the voters would find this bold and admirable. Instead, they thought abandoning his promise to work with the state Legislature was irresponsible and juvenile and resented having to pay millions in public funds to hold an superfluous election.

Schwarzenegger's arrogance was initially part of his populist appeal -- but it led him to underestimate his opponents. Last November, when members of the California Nurses Association protested his decision to scuttle new regulations requiring minimum nursing ratios at hospitals -- a ratio worked out through years of legislative compromise -- he retorted that they were just "special interests" and boasted that he was "always kicking their butts." The nurses union declared war and pursued him at every public appearance with remarkable tenacity. It turns out that people actually like nurses, even more than they like Schwarzenegger. The governor was always on the defensive after November, dealing with flying pickets wherever he went.

Schwarzenegger assumed he could pick a fight with every center of power in the state and win. He went after career politicians with his redistricting initiative, and attacked every single public employees union with his initiative banning unions from political contributions. He didn't stagger these battles over a couple of years but declared simultaneous war on the entire political establishment, which spent tens of millions of dollars to defeat him.

"If you think back two years, there was a lot of hope, and [Schwarzenegger] could sell ice to an Eskimo," says Bob Mulholland, a spokesman for the California Democratic Party. "Two years of personal attacks later, he can't sell two-by-fours to carpenters. The election proved that. How could a guy shoot himself in both feet? But Schwarzenegger did it."

The irony is that in some ways, Schwarzenegger was right. The redistricting process, for example, is a national disgrace. Thanks to computer-aided demographic research, politicians can now draw politically homogeneous districts that guarantee reelection for incumbents year after year. This cripples the ability of Asian and Latino communities to build healthy politics and promote candidates for higher office. And as long as incumbents never have to explain themselves to constituents who don't agree with them, they're free to adopt extremist views, poisoning the national dialogue and wiping out the art of legislative compromise.

In addition, some of the public unions are ruining the state. Five years ago, police and firefighter unions forced cities around California to give them a fat new pension plan known as "Three percent at fifty." Now, the pensions are threatening to bankrupt these cities, which must sometimes pay retired cops up to 90 percent of their salaries for life. Taking power from unions that inflict this kind of pain on the people they purport to serve doesn't seem like such a bad idea.

But Schwarzenegger could never make a serious case for his proposals. He was too overwhelmed by the arrogant, swaggering public image he so studiously crafted, and irritated voters just stopped listening. But that's hubris for you. Schwarzenegger has led such a charmed life that he never considered that someday, someone would tell him no. This cocky self-assuredness made him the darling of South Park conservatives, but left him with a vast blind spot that may destroy his political career.

Libertarian intellectuals now face a stark problem. A growing army of conservatives distrust the Bush administration's utter lack of spending restraint and despise his efforts to regulate morality and pander to the religious right. They know that hawking Terri Schiavo to the Bible Belt will cost them millions of moderate voters, and that xenophobic race-baiting about securing the border will sour the Republican Party in the minds of the vast, emerging Latino electorate. They have been searching for someone to snatch conservatism from the likes of Judge Roy Moore and reconstitute it in the spirit of Newt Gingrich, Edmund Burke, and H.L. Mencken. They thought they had found that man in Schwarzenegger. Millions of Californians just told them how wrong they were.

Shares