Every Nov. 22 we are haunted by the unquiet ghost of John F. Kennedy, and last week’s anniversary of his assassination was no exception. As usual, none of the flurry of press reports taking note of the mournful occasion shed any new light on what remains the greatest unsolved mystery of the 20th century. The national dialogue about the case remains stuck where Oliver Stone’s explosive 1991 film “JFK” and Gerald Posner’s bestselling 1993 rebuttal, “Case Closed,” left it. Stone’s dark dream, peopled by sinister government officials and demons from the underworld, had the virtue of channeling the deepest fears of the American public, a consistent majority of which continues to believe JFK was the victim of a conspiracy. Posner’s book, which mounted a game defense of the lone gunman theory in the face of a growing body of contrary evidence, had the virtue of simplicity and calming reassurance.

Though you wouldn’t know it from following the media coverage, there have been new developments in the case during the past dozen years — many of them sparked by the thousands of once secret documents released by the government as a result of the furor around Stone’s film. (Millions of other pages remain bottled up in agencies like the CIA, in defiance of the 1992 JFK Assassination Records Collection Act.) Some of this recently unearthed information is now beginning to appear in new books, including “Ultimate Sacrifice,” this year’s most highly touted JFK assassination book.

Written by two independent researchers who spent 17 years on the book — former science fiction graphic novelist Lamar Waldron and Air America radio host Thom Hartmann — the book arrives in a blaze of publicity about its provocative conclusions. Columnist Liz Smith excitedly announced that the book was the “last word” on the Kennedy mystery.

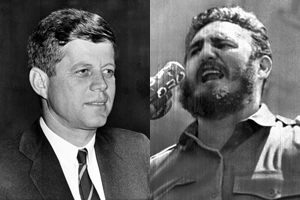

The “revelations” in “Ultimate Sacrifice” are indeed as “startling” as the book jacket promises. The authors contend that before he was killed, President Kennedy was conspiring with a high Cuban official to overthrow Fidel Castro on Dec. 1, 1963 — a coup that would have been quickly backed up by a U.S. military invasion of the island. The plot was discovered and infiltrated by the Mafia, which then took the opportunity to assassinate JFK, knowing federal law officials (including the president’s brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, who was in charge of the Cuba operation) would be blocked from pursuing the guilty mobsters out of fear that the top-secret operation would be revealed.

While the authors’ thesis is provocative, it is not convincing. The Kennedys undeniably regarded Castro as a major irritant and pursued a variety of schemes to remove him, but there is no compelling evidence that the coup/invasion plan was as imminent as the authors contend. By 1963, after the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion and the heart-thumping nuclear brinksmanship of the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Kennedys were in no mood for any high-stakes Cuba gambits that had the potential to come crashing down loudly around them. Before they entertained such a risky venture, they would have thrashed out the idea within a circle of their most trusted national security advisors — a painful lesson they had learned from the Bay of Pigs fiasco, a closely held plot that JFK had been steamrolled into by his top two CIA officials, Allen Dulles and Richard Bissell.

But according to Waldron and Hartmann, though the exceedingly ambitious coup/invasion plan was supposedly just days away from being implemented when Kennedy was assassinated, key U.S. military officials like Defense Secretary Robert McNamara had still not been told about it. The idea that the Kennedys would seriously undertake such a risky operation without the participation of their defense secretary, a man they trusted and admired more than any other Cabinet member, defies reason. (For the record, McNamara himself has firmly rejected the notion that JFK was plotting a major Cuba intervention in late 1963, in an interview I conducted with him earlier this year for a book on the Kennedy brothers.)

The Kennedy administration was in the habit of churning out a blizzard of proposals for how to deal with the Castro problem, most of which the president never formally endorsed. It seems that Waldron and Hartmann have confused what were contingency plans for a coup in Cuba for the real deal. In fact, an exchange of government memos in early December 1963 between CIA director John McCone and State Department official U. Alexis Johnson that was released under the JFK Act — and apparently overlooked by the authors — specifically refers to the coup plot as a “contingency plan.” On Dec. 6, 1963, Johnson wrote McCone, “For the past several months, an interagency staff effort has been devoted to developing a contingency plan for a coup in Cuba … The plan provides a conceptual basis for U.S. response to a Cuban military coup.” The key words here are, of course, “contingency” and “conceptual basis” — neither of which suggests anything definite or fully authorized.

Waldron and Hartmann rely on two key sources for their theory about the coup plan (which they refer to as “C-Day,” a code name they concede is entirely their own creation, adding to its chimerical quality) — former Secretary of State Dean Rusk and a Bay of Pigs veteran named Enrique “Harry” Ruiz-Williams, Robert Kennedy’s closest friend and ally in the Cuban exile community, both of whom they interviewed before the two men’s deaths. But, according to Rusk, he only learned of the coup plan after the Kennedy assassination from sources within the Johnson administration. And considering the legendary antipathy between Bobby Kennedy and Johnson loyalists like Rusk, who often portrayed the Kennedy brothers as fanatical on the subject of Castro, this testimony must be viewed with some skepticism.

Ruiz-Williams, on the other hand, was very friendly with Bobby, phoning him on a regular basis and joining the Kennedy family on ski trips. But his belief that a Kennedy-backed assault on the Castro regime was imminent might be a case of wishful thinking. While Bobby’s romantic nature did open his heart to brave anti-Castro adventurers like Ruiz-Williams, RFK’s hardheaded side always dominated when it came to protecting the interests of his older brother. And Bobby knew that as the 1964 election year loomed, his brother’s main interest when it came to Cuba was keeping it off the front pages. That meant making sure the volatile Cuban exiles were as quiet and content as possible, which is why Bobby was working aggressively to encourage anti-Castro leaders to set up their operations in distant Central America bases, with the vague promise that the U.S. would support their efforts to return to Havana.

At the same time, the Kennedys were secretly pursuing a peace track with Castro, to the fury of the CIA officials and exile leaders who found out about it, seeing it as another blatant example of Kennedy double-dealing and appeasement. Waldron and Hartmann play down these back-channel negotiations with Castro, writing that they were failing to make progress. But the talks, which were spearheaded by a trusted Kennedy emissary at the U.N., William Attwood, were very much alive when JFK went to Dallas.

The authors further undermine their “C-Day” theory by refusing to name the high Cuban official who allegedly conspired with the Kennedy administration to overthrow Castro. They decided to withhold his name out of deference to national security laws, they write, a puzzling decision considering how long ago the Kennedy-Castro drama receded into the mists of history from the center stage of geopolitical confrontation. “We are confident that over time, the judgment of history will show that we made the right decision regarding the C-Day coup leader, and that we acted in accordance with National Security law.” This flag-waving statement will surely win the hearts of anonymous bureaucrats in Langley, but it will only alienate inquisitive readers.

While bowing to “national security,” Waldron and Thomas cannot help themselves from heavily implying who the Cuban coup leader was — none other than the charismatic icon of the Cuban revolution, Che Guevara, who by 1963 was chafing under Castro’s heavy-handed reign and pro-Soviet tilt. If all the authors’ winking and nodding about Che really is meant to point to him as the coup leader, this raises a whole other set of questions, not least of which is why the Kennedys would possibly regard the even more incendiary Guevara as a better option than Castro.

If C-Day is a stretch, the second part of the book’s argument — that the Mafia assassinated Kennedy with complete government immunity, using their inside knowledge of the top-secret plan to escape prosecution — is even harder to swallow. Waldron and Hartmann portray a group of mobsters so brilliant and powerful they are able to manipulate national security agencies and frame one of their operatives, Lee Harvey Oswald; organize sophisticated assassination operations against JFK in three separate cities (including, finally, Dallas); and then orchestrate one of the most elaborate and foolproof coverups in history. Think of some awesome hybrid of Tony Soprano and Henry Kissinger.

It is true that Santo Trafficante, Carlos Marcello and Johnny Rosselli — the three mobsters whom the authors accuse of plotting JFK’s demise — were cunning and cruel organized crime chieftains. And they hated the Kennedys for allegedly using their services and then cracking down on them. But even they lacked the ability to pull off a brazen regicide like this by themselves. And if they did, “national security concerns” might have been enough to stop investigators like Waldron and Hartmann, but never Bobby Kennedy, whose protective zeal toward his brother was legendary. All the attorney general would have had to do was explain the national security concerns in the judge’s private chambers, and once the coup plan was safely under wraps, his prosecutors would have been free to take the gloves off and go after his brother’s murderers.

The biggest puzzler about the authors’ Mafia theory is this: Why in the world would organized crime bosses, who had been scheming to return to Havana ever since Castro’s revolutionary government had evicted them from their immensely lucrative casinos, knock off Kennedy just days before he was about to knock off Castro? Here again, “Ultimate Sacrifice” fails the basic logic test.

The authors belabor their thesis for nearly 900 punishing and unforgivably repetitive pages. But at the end of their exhausting trek, they are no closer to proving their case than when they started.

It’s a shame that “Ultimate Sacrifice” is hobbled by a cockeyed assassination theory and swollen size. Because buried in this weighty tome are a number of shiny nuggets that shed light on the case. Among the important sources Waldron and Hartmann spoke to was JFK’s “Irish Mafia” sidekick Dave Powers, who was riding 10 feet behind Kennedy’s limousine in Dallas and told them he clearly saw at least two shots from the infamous grassy knoll in front of the motorcade — evidence of a conspiracy, since Oswald was allegedly firing from the rear, on the 6th floor of the Texas Book Depository building. Powers, who spoke to the authors before his death in 1998, told them he felt they were “riding into an ambush” and said that he was pressured to change his story by the Warren Commission. (For some reason, the authors perversely stash most of Powers’ story in the acknowledgments, at the far end of the book.)

Waldron and Hartmann also chronicle in detail for the first time an aborted plot to kill Kennedy during a motorcade in Tampa, Fla., four days before he was cut down in Dallas — as well as fleshing out an earlier plot in Chicago not widely known about. These three plots, which bore remarkable similarities, suggest that JFK was being relentlessly stalked in his final days by a sophisticated group of conspirators.

“Ultimate Sacrifice” also presents a convincing portrait of Oswald as the “patsy” he told the world he was as he was being escorted through the Dallas police station — a low-level intelligence operative whom the authors contend was being groomed by the CIA as the fall guy in an assassination plot against Castro and was then ensnared in the scheme to kill Kennedy. And the book presents persuasive evidence that Jack Ruby, far from being the distraught citizen who shot Oswald out of deep affection for the Kennedy family, was actually a longtime Mafia errand boy and enforcer who was paid off by associates of Teamster boss Jimmy Hoffa, RFK’s public enemy No. 1, to silence Oswald before he could tell a court everything he knew.

The authors also examine the numerous tension points between the Kennedys and the CIA, pointing to a number of insubordinate acts by the agency related to the administration’s Cuba policy that can only be described as treasonous, including trying to sabotage the Kennedy-Castro peace feelers by pursuing an assassination plot against the Cuban leader without the Kennedys’ knowledge or assent.

Also unnerving is the authors’ account of Cuban exile Alberto Fowler, a Kennedy-hating Bay of Pigs veteran and probable CIA asset who seemed to be stalking JFK in his final days, moving into the house next door to the Kennedys’ Palm Beach mansion on the weekend of Nov. 17, 1963, where JFK was sequestered while finishing a speech he was to deliver in Miami.

While the authors take pains to (repeatedly) exonerate the CIA in the killing of Kennedy, their book actually winds up raising serious questions about the agency’s possible role in the crime. Though it’s not the authors’ scenario, after finishing “Ultimate Sacrifice” the reader is left with the unmistakable impression that the assassination was probably the work of a conspiracy involving elements of the CIA, Mafia and anti-Kennedy Cuban exiles — a cabal that was working to terminate Castro’s reign (by any means necessary) and turned its guns instead against Kennedy. This is precisely what Robert Kennedy himself immediately suspected on the afternoon of Nov. 22, 1963, though Waldron and Hartmann wrongly assert that Bobby blamed only the Mafia (and New Orleans godfather Carlos Marcello in particular) for the death of his brother. In truth, CIA officials like David Atlee Phillips, William Harvey and David Morales; gangsters like Marcello, Trafficante and Rosselli; and anti-Castro Cuban leaders like Manuel Artime and Tony Varona were so intertwined in their blood lust against Castro that it’s difficult to separate them.

“Ultimate Sacrifice” is certainly not “the last word” on the Kennedy assassination. But it keeps the pot boiling. There are sure to be more books on the subject next fall. They will continue coming as long as the American public feels it is still not getting the full truth about the violent removal from office of its 35th president.