With all the hubbub about intelligent design these days, we don’t seem to hear much about creationism. The word sounds musty. But while intelligent design is the theory that believers take out in public, you can’t help suspecting it’s creationism that many of them really love. So there’s something refreshing in Christine Rosen’s account of her fourth-grade science class at Keswick Christian School in the early ’80s. In “My Fundamentalist Education: A Memoir of a Divine Girlhood,”Rosen recalls that the students had no need to lug around a science textbook. For geology lessons, they turned to Genesis 1:1. The way her teacher presented natural selection, it sounded more like an insult than a theory: “Evolution says we all come from apes and monkeys!” she exclaimed. “Who do you think is right, Darwin or God?”

In that face-off, the competitive edge enjoyed by omniscient beings was further enhanced by home team advantage. At Keswick, and in the surrounding town of St. Petersburg, Fla., religious faith was as pervasive as the heat. This entertaining memoir re-creates Rosen’s childhood in St. Petersburg, a land of malls, old people and Jesus. Few sociological indicators are more straightforward than bumper stickers, and Rosen repeatedly invokes them to convey Floridian culture. In parking lots, bumper stickers on white Buicks bragged, “I’m spending my children’s inheritance!” For Keswick parents’ vehicles, popular choices included “Jesus Saves!” and “God Is My Copilot!”

Rosen has strayed far from those origins. Now a resident of Washington, D.C., she has married a Jew (the legal scholar Jeffrey Rosen), earned a Ph.D. in history, and authored a previous book, “Preaching Eugenics: Religious Leaders and the American Eugenics Movement.” As a contributor to the Weekly Standard and the Wall Street Journal, she is not a total apostate to her conservative upbringing, but she has gone “entirely secular.” In the streets on which she now drives, a good number of cars probably sport disintegrating Kerry-Edwards ’04 bumper stickers.

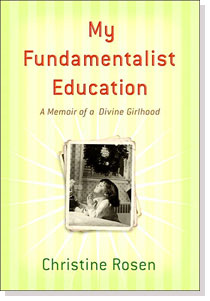

This crowd also appears to be her memoir’s target audience. “My Fundamentalist Education” promises a glimpse into a world we soy latte addicts don’t understand but can no longer dismiss. Controversy about evolution, Christian blockbusters in Hollywood, a president who speaks in biblical code: Christianity is hot, and Rosen’s background is, suddenly, marketable. With her intelligence and tongue-in-cheek tone, she comes across as the ideal liaison: a former insider who will explain fundamentalism while allowing us to chuckle at it.

Rosen was born in 1973 to perfunctorily Methodist parents. Her father and stepmother sent her to Keswick without quite registering the degree of its zealotry. (The school was affiliated with the Moody Bible Institute, a Chicago-based fundamentalist Protestant institution committed to “separation from the world” and “winning souls to Christ.”) But as a kindergartner, Rosen latched on to the teachings, developing a love for the Bible and a “spiritual crush” on Moses. To a Floridian, she muses rather cutely, the Bible came in handy for making sense of the landscape she inhabited. “The Bible stories I heard every day — stories about burning bushes, plagues, and other freakish expressions of God’s power over nature — seemed sensible in a place where we shared our world with sharks, scorpions, sting rays, snakes, fire ants” and other exotic organisms.

With a sharp eye, keen wit and agile prose, Rosen looks back in amusement at Keswick’s rituals. In a “Walk Thru the Bible” seminar, second-grade students learned to illustrate biblical events with hand gestures: “We drew squiggly lines in the air to represent major rivers in the Middle East, and vast expanses of Numbers and Deuteronomy were dispatched with a grand sweep of the arm.” As for sex education, there were naturally no demonstrations involving condoms on bananas. The preferred pedagogical prop was a brick. During junior year at Keswick, boys and girls would be paired off with joint responsibility for a “Brick Baby,” symbolizing the inevitable consequence of succumbing to the lust of the flesh. In addition to “harlotry,” Keswick educators sounded the alarm against rock music, dancing, communists and the local 7-Eleven, whose insistence on stocking Playboy sparked a faculty-mandated boycott.

Christine, dutiful and devout, heeded her teachers. But as she was also smart and inquisitive, subversive questions were bound to pop into her head. In science class, she wasn’t about to ditch God for Darwin, but, having learned about fossils over the summer, she groped for a way to reconcile the two. Sounding just a few mental acrobatics away from inventing intelligent design herself, she wondered, “Perhaps the Grand Canyon had been created by the Great Flood, as my teacher said, but the Great Flood actually happened much, much longer ago? Perhaps the dinosaurs lived long before the Bible happened…”

As for sex, she had no intention of performing the act, not least because she had no notion of what it involved. In the eighth grade, when her teachers launched their initial campaign against fornication, her fantasy life was restricted to imagining alternative endings to “Choose Your Own Adventure” stories. Under Keswick’s tutelage, she developed a terror of premarital sex. But the warnings did awaken her curiosity, leading her to mine a friend’s father’s medical books and the “Sweet Valley High” series for clues about the forbidden subject. Rosen documents her nascent skepticism as she started to chafe against all the no-nos, although in the narrative it never grows beyond the budding stages.

School occupies the foreground of this memoir; in the background is a portrait of a split family. Rosen lived with her father, stepmother Pam, older sister Cathy and younger half-sister Cindy in a loving, relaxed household. On weekends, she visited her biological mother, who left the family not long after Rosen’s baptism. Through the light-hearted humor, an unsettling fact emerges: Rosen is deeply estranged from her mother, also known as Biomom. Typically, the fraught mother-daughter relationship would be the anguished focus of a memoir. Here, its subplot status feels disorienting, like the memoirist’s equivalent of burying the lead of a news story. The novelty is ultimately welcome; we have no need for another saga of family dysfunction. But those stories are compelling for a reason, and in this case, the book’s emotional energy definitely lies in Rosen’s feelings about her mother. Discussing them, her tone sobers up, grows careful. Her mother “was different from the other adults I knew — and not necessarily in a good way.” She compares her mother’s affection to the cape in a bullfight. “Seeing it before me — bright, alluring, as riveting as crimson — I charged headlong toward it. Just as I came close to reaching it, however, it would elude me.”

Despite those somber sentiments, some of the book’s funniest passages are those starring her mother. She found religion after Christine did, yet embraced it with equal fervor. But her Christianity was evangelical rather than fundamentalist. (That the two branches differ dramatically might come as news to some readers. Indeed, the more ignorant among us would have appreciated further elaboration on their contrasts.) “At school we praised the Lord through soothing organ music and the recitation of the Lord’s Prayer,” Rosen writes. “In Mom’s churches, they praised the Lord with a Pearl Forum Fusion five-piece drum set and electric guitar with wa-wa pedal.” Miracle cures and speaking in tongues, encouraged in evangelism, were frowned upon in fundamentalist circles. Christine and her mother alike, however, anticipated imminent end times, or “the rapture,” which proved a useful disciplinary technique. Faced with misbehavior, her mother would sigh, “There’s nothing I can do if you don’t get raptured with me.”

Rosen’s mother, like many of the Christians in the book, comes across as something of a parody. That is one reason “My Fundamentalist Education,” for all its humor and vivid prose, disappoints. Readers might have expected alarming revelations of extremist beliefs and behavior; or we might have hoped for soothing assurances that we’re all not so different from each other, no matter our beliefs. We get neither. Instead, Rosen colors in the details of our vague stereotypes.

Also disappointing is the epilogue, a chapter called “The Hereafter,” in which Rosen provides a series of updates. (Here we learn that her mother turned out to be mentally ill with what sounds like bipolar disorder. But she is alive, if not well, making her public christening as Biomom a little shocking.) In an elegiac mood, Rosen concludes that her teachers at Keswick fostered a “respectful yet questioning tone,” and a “combination of engagement with the text and the first glimmerings of skepticism.” But this generous assessment finds little support in the earlier portraits of hectoring schoolmarms. That Rosen did begin to question their teachings was a tribute to her, not to them.

At the end of her account, when Rosen is 12 and finishing the eighth grade, her parents belatedly recognize Keswick’s extremism — thanks to the 7-Eleven boycott — and decide to transfer Rosen and her sister to another school. At this point, she’s begun to itch with curiosity: “The longer I spent inside this closed world, the more eager I was to see what was on the other side of that wall.” But when she finally scales the wall, the action takes place offstage. Fast-forward to the epilogue: “In the end, I found I could not do the many things I wanted to do in the world if I continued in a faith whose first principle is separation from it.” Instead of telling a story, this memoir sets a scene. Just as momentum starts to build, the author vaults over its culmination. The chronicle of Rosen’s fundamentalist education shares a shortcoming with its curriculum: too little evolution.