"Ghosts from a beautiful dream." That's how country-and-western star Marty Stuart refers to such living luminaries of country music as Loretta Lynn, George Jones, Willie Nelson, Merle Haggard and others in his liner notes for Martina McBride's latest album, "Timeless." Could any description be more loving? Or more withering?

To describe country music as a place where living greats have become ghosts is to describe it as having betrayed its past, probably the most damning thing you could say about a genre that claims to have such respect for tradition.

I stopped listening to contemporary country music a few years back. I was tired of the anonymity of the songwriting, of arrangements that sounded like some postmodern representation of country instead of music itself. And the music that sprang up in opposition, alt-country, was usually about as much fun as sitting bare-ass naked on a splintery bench. The alt-country artists sounded as if any expression of pleasure was a sellout. If mainstream country had become the equivalent of a shiny new SUV, alt-country was a dirty window with dead flies littering the sill. A choice between that shopping-mall dominatrix Shania Twain or Lucinda Williams' wallflower moping was no choice at all.

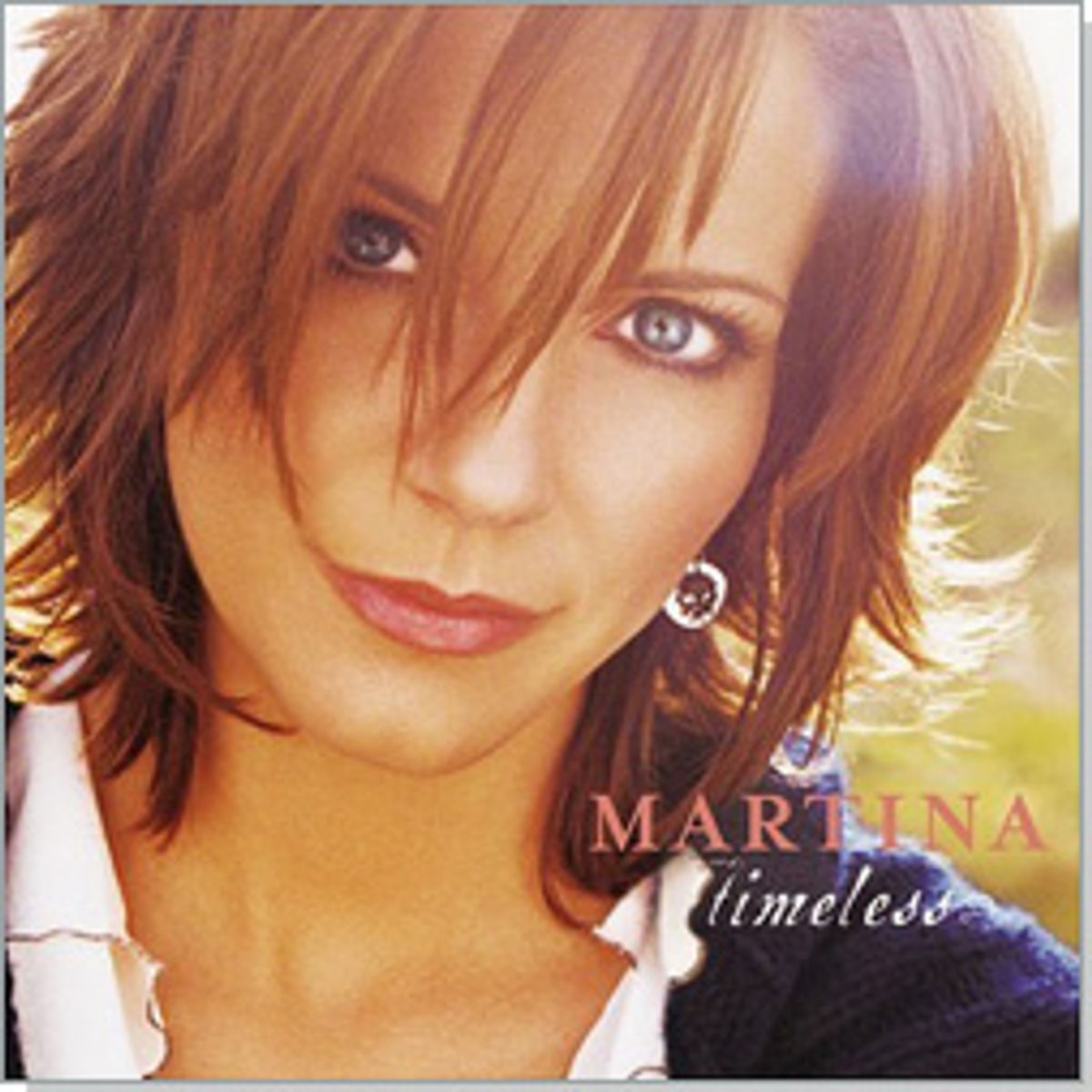

What does it say that two of the biggest icons in country, Dolly Parton and George Jones, and country's biggest contemporary female star, Martina McBride, have all turned their backs on contemporary country on their new records? Parton's "Those Were the Days" is a selection of folk-rock covers from the '60s and '70s; George Jones' "Hits I Missed ... And One I Didn't" consists of songs he turned down that became hits for other artists. The Parton and Jones albums aren't played on country radio, but for Martina McBride to release "Timeless," consisting entirely of classic country hits, is, whether she intends it to be or not, a gauntlet thrown at the facelessness of contemporary country. (That "Timeless" entered the country charts at No. 1 -- and that Lee Ann Womack's "There's More Where That Came From," which, from the cover art to the sound of the music, harked back to '70s country, was one of last year's biggest country albums -- suggests that some country fans may be willing to throw down the gauntlet as well.)

Ever since her debut in 1992, Martina McBride has been a perpetual ray of hope in country music. She's never equaled her first big hit, "Independence Day" -- the witness of a true believer delivered as a scorched-earth sermon -- which, after Nirvana's "Smells Like Teen Spirit," is the greatest single of the '90s. Her choice of material, her arrangements and production, have been as slick as anything mainstream country has to offer. And some of the songs, most notably those on 1997's "Evolution," had a treacly self-actualization subtext (the faux feminism country music adopted as a reaction to what has been so dimwittedly read as the submissiveness of Tammy Wynette's "Stand By Your Man").

Why, then, do I still listen to everything McBride does as soon as she does it? Because she has never once sounded defined by the commercial slickness of her material or musicians, has never seemed to be phoning it in, has never not sounded like a real person. Martina McBride possesses one of the truest voices I know, and while I have often wished for her to travel rougher territory, I have never doubted her sincerity or integrity.

Now, when you say someone has a voice, you have to be clear what you mean. The same can be said of every Trivial-Pursuit-answer-in-waiting on "American Idol." What separates McBride from them and from most of her country and pop contemporaries is that she's a singer. McBride shuns vocal gymnastics; she never sings four syllables where one will do. Her voice never goes shrill; the bigger it gets, the freer it becomes. Rare among contemporary singers, McBride is emotionally unfettered and yet also has an innate sense of what to hold back, how to suggest.

McBride opens "Timeless" with Hank Williams' "You Win Again" as if it were a statement of ethics. The utter simplicity of the song, her faith in it and her refusal to embellish become a way of returning not just herself but the entire genre of country back to priorities.

At a generous 18 tracks, "Timeless" is the most satisfying album McBride has made, largely because she's got great material, and also because of the way the material is presented. Acting as her own producer, McBride and her manager-husband, John (who recorded and mixed "Timeless"), have used mostly analog equipment (no guitars or amps newer than 1965, for example) to give the album a fat, warm sound, the sound you'd hear when most of these songs first hit the radio.

There are covers here of songs by Ray Price, Tammy Wynette, Johnny Cash, Ernest Tubb and others. All are good. Two of the songs, Buddy Holly's string-laden ballad "True Love Ways" and "I Can't Stop Loving You," the Don Gibson song that was a smash for Ray Charles, virtually copy the arrangements of the song's best-known versions. ("I Can't Stop Loving You" even has the white-sounding backup singers Ray used.) That's worth noting because there's nothing that sounds like mimicry in McBride's vocals. For a white country singer to cover "I Can't Stop Loving You," a song that a black R&B master took from another white country singer, and still make her version true, suggests both chutzpah and confidence, the kind of confidence that doesn't need to boast.

If I had to choose a song to sum up the special poignance country music is capable of, it might well be "Satin Sheets," Jeanne Pruett's 1973 song, which she herself promoted all the way to No. 1 after her record company told her it was "too country," and which McBride tackles on "Timeless." Pruett discovered it on an unsolicited tape sent to her by its composer, a Minneapolis factory worker named John Volinkaty. It's a song about someone who's found a life of unimagined luxury but who still pines for the true love who will give her what money can't buy. That's a classic setup for a country weeper, but the authenticity of the song can be summed up by one line -- "tailor-mades upon my back." That's an example of specificity as instinctive genius. No one used to fine clothing would ever speak of it in that way, and the language reveals, as does the unalloyed carnal longing in McBride's vocal, country's simultaneous wish for material comfort and the distrust of it. The satin sheets and tailor-mades are distractions; emotion is the only real thing.

That's as good a metaphor for what's true in McBride's music as anything could be. But the languid soaring she does on the song that closes "Timeless," Kris Kristofferson's "Help Me Make It Through the Night," sums up the album in another way. When Sammi Smith recorded it in 1971, it had the same impact on country that the Shirelles' singing "Will You Love Me Tomorrow" had on rock 'n' roll in 1962. That is, it was an open expression of a sexuality women were not meant to feel, let alone acknowledge. There's something like a swoon in McBride's voice in the way she accentuates the verb in "I don't care what's right or wrong," as if she could will herself into the abandon she's turning to for comfort. She's holding coldness at bay here; beneath the longing in the singer's voice is a hardness that says she knows just how temporary the comfort she seeks will be.

Emotionally, the song is all of a piece, and yet the first line of the chorus, "Yesterday is dead and gone," is the only untruth on the album. McBride sings each song on "Timeless" not as a part of history, as something dead and gone, but as though each were a living thing, because, for her, these songs are alive. On the best album she's made, Martina McBride has landed nearly all of contemporary country music in a pickle: How can we be satisfied with country music as it is now when this is its living past?

Shares